The essence of Palestinian resilience, survival, and resistance is rooted in dispossession.

One of my earliest memories is of the summer of 1990. My family and I were vacationing in Amman from Kuwait where, overnight, the furnished apartment in which we were staying became our new home. I remember wall to wall red carpets and my mother sitting on the lumpy couch with her head on her fist for hours on end, waiting for the phone to ring. I remember my brothers trying to distract me from something big by playing with their annoying little sister a lot more than they usually did. I remember a sense of loss, uncertainty, a lot of worried adults, and learning that a person sometimes had to be strong — or maybe that’s what I tell myself today to try and derive some kind of lesson from the experience of a scared and confused little girl.

Iraq had invaded Kuwait, where my father had stayed behind. We had no idea where he was and the adults were constantly speaking in hushed tones about borders and Saddam and Israel. At any point in time, no matter where we are in the world, Palestinians are guaranteed to be found having heated political conversations while an unending stream of news plays on our televisions. Arab children grow up with these two constants always in the background, which helps create and temper their understanding of war. Although I may have understood in some way what war was that summer, what I didn’t understand was why we would never see our home in Kuwait ever again. It was my first lesson on the tumultuous realities faced by citizenship-less Palestinians like my family members.

I love hearing my father tell the story of his escape from Kuwait: a precarious, days-long journey by car from Kuwait City to Amman by way of Baghdad, where he made sure to sing the praises of Saddam Hussein to any questioning Iraqi soldiers along the way. It wasn’t the first and wouldn’t be the last time my father would have to escape war. Over the years he has developed a knack for inadvertently ending up in conflict zones: he landed in Beirut on April 13th 1975 — the day of the start of the Lebanese civil war — and got smuggled out of south Lebanon during the 2006 Israeli assault. It has become a running joke in our family.

When my father talks about his childhood, his first memories are of the different refugee camps in which he grew up in the south of Lebanon: El Buss, Rashidiyeh — “oh, and we had cousins in Tal el Zaatar.” Whenever he talks about the camps, he always makes sure to mention the cousins in the Tal el Zaatar camp. “Your cousins were massacred in Tal el Zaatar,” he never failed to remind me. As if to say that his own experience as an exile and refugee, terrible as it was, could have been much worse. In this way I learned how the Palestinian cause dictates that each painful experience can be eclipsed by one even more terrible.

The paradox of our lives as Palestinians in the West is that we are forced to simultaneously carry and prove our dispossession.

I see the Palestinian struggle as a web, with the Nakba at its center. Everything traces back to it, and every connecting thread is a massacre, a demolition, a martyr, a siege, an intifada; painful realities in the web that expand every day, connecting the dead, the exiled, the occupied and the imprisoned. When my dad mentions the cousins who were massacred in Tal el Zaatar, it is the pain within the web radiating, like when a single neuron in our brain lights up, it excites the ones around it — our stories cannot be told without stirring up all the tragic events that surround them, without activating the collective Palestinian experience. It permeates our past and present, and finds itself in everything a Palestinian touches, even in the smallest of ways. Such as when I accidentally discovered that my parents — independently from one another — both included some variation of the year 1948 in most of their internet passwords. Or how any time we were anywhere near the border with Palestine, my grandmother made sure to point to the distant landscape to remind us that this was the land where she was born and that we all belonged to. It took only the look in her eyes to understand that we did, and when I looked out onto the sprawling green hills with my own eyes (a perfect landscape), I fell instantly in love.

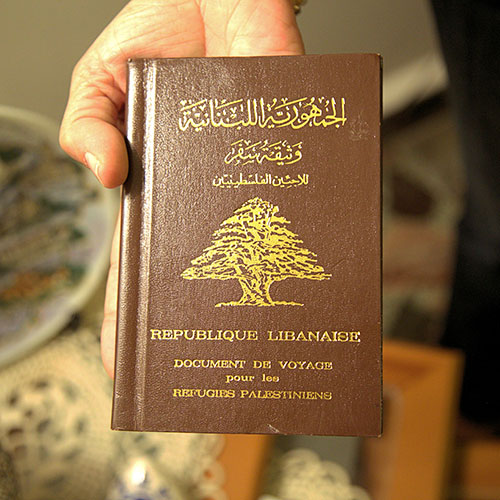

The violent expulsion of Palestinians by Zionist militias in 1948 forcibly turned hundreds of thousands of Palestinians into refugees in neighboring Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. Those born in Lebanon, such as my father, are issued a travel document by the Lebanese government. This was the status my brothers and I inherited even though we had never lived let alone been to Lebanon; one of many paradoxes that often plagues the bureaucracy limbo that most Palestinians inherit from birth. The travel document, also known as a laissez-passer, was meant to facilitate travel for refugees. In practice, whenever we traveled within the Arab world, the laissez-passer served mostly to highlight our dispossession, and was the reason we experienced so much pushback from immigration officials. After many years of traveling, my father was well-versed in the very specific visa requirements for Palestinian refugees, but that never stopped immigration officials in the Arab world from creating unnecessary hurdles whenever we were at a border or an airport; I’d often hear my parents complain of anti-Palestinian racism (carefully and under their breath, lest they trigger the high-on-his-own power immigration official) as we waited around for our stacks of papers and signed documents to be legitimized.

The laissez-passer itself evokes the many ways that various Arab governments have dealt with Palestinian refugees since the Nakba. At first glance, the small booklet might pass as a legitimate passport; the cover is bound in respectable brown leather and embossed in gold with a Lebanese cedar and fancy lettering that says Republique Libanais, document de voyage pour les réfugiés Palestiniens. Upon further scrutiny, the cover is revealed to be stiff and unyielding, and underneath the fancy leather facade is a familiar material; cheap, hollow, flimsy cardboard. On the second page, the information is hand-written in black ink, next to it my childhood photo carefully taped to the page. With official government emblems, signed and stamped by important people, it is ensuring that I am, officially, a Palestinian — one who will, officially, never belong to this country that issued these papers, Lebanon.

My family and I became Canadian citizens in the late ‘90s, and the laissez-passers have since transformed from functional necessities to relics of our displacement that my mother still keeps in a safe on the same shelf as her gold jewelry. They may be defunct, but the imperfect booklets are one of the few ways that we can still prove that we are Palestinian in a world that has allowed our Israeli oppressor to put into question our belonging to the land, and, by extension, our very existence. From time to time, I ask my mother to take mine out of the safe so that I can look at it — to remind myself maybe — to see this one of very few physical representations of our legacy, our dispossession.

Here in the West, when someone asks where I’m from, I hope to keep their attention long enough as I try my best to summarize the last one hundred years of Middle Eastern colonial history. Talking about the Nakba or the Zionist occupation of Palestine means engaging in a carefully crafted performance years in the making — a choreographed dance that attempts to charm my audience while precariously navigating the minefield of fallacious labels that Zionists have set down for Palestinians and our supporters. This dance is often performed while Israel is razing entire neighborhoods and decimating families — when colleagues and acquaintances suddenly decide that now is the time to glance over at a seventy-six year long disaster and hope to get the SparkNotes version from me.

A few weeks after October 7th, I was waiting in line at the gas station when a friendly Indigenous man struck up a conversation with me. He spoke eagerly about his Inuit heritage and how he was visiting from Nunavut. Then, he asked the dreaded question: “Where are you from?” The line we were waiting in wasn’t long enough for this conversation. But I was won over by his friendly approach. “I’m Palestinian.” His smile faded. After a short pause he simply said, “We are the same.” It took all my strength not to break down in front of the long line of people.

The paradox of our lives as Palestinians in the West is that we are forced to simultaneously carry and prove our dispossession. Since the start of the genocide in Gaza, I’ve been asked multiple times whether I have family “over there.” Most of my extended family members no longer, in fact, live in any part of historic Palestine. They are refugees strewn all over the world in eleven different countries — generations of family broken up by the trauma of ethnic cleansing. I can’t help but feel a sense of debasement when attempting to explain this to people who often confuse Palestine with Pakistan, and can point to neither on a map.

You only need to attend a Palestinian gathering to see the extent of this exile first-hand. Like when I went to one cousin’s wedding (in Arizona) and met for the first time two other cousins (from Denmark and Lebanon). It was at this wedding where, in a twilight-zone moment, a member of the zaffeh performers introduced himself as Naji El-Ali. “That Naji El-Ali?” I asked, confused. “Yes” he said, amused. “He was my grandfather.”

I felt the web reverberate.

Though my father beat extreme odds to make a life for our family in Kuwait, we could no longer go back to our home there, nor could we enjoy a dignified life in Lebanon where, despite being born and raised as lifelong residents of the country, Palestinians are denied from working certain jobs or even owning or inheriting any property. Dad was getting tired of being at the mercy of one regional conflict after another and decided to try his luck by applying for immigration to the US and Canada simultaneously, ultimately choosing whichever country accepted our application first. It was a final roll of the dice, one of many that determines the fate of Palestinian refugees over the course of their lives.

For the first few years after we moved to Montreal, whenever someone asked my mother where we were from, she’d often say we were Jordanian, and I understood that this was done as a form of protection, so I did it too. As newcomers, there was a sense of having to constantly grapple with the fact that our ethnicity was a disadvantage, that our Palestinian identity made us a target, and so we did what we thought was necessary to make us less threatening to locals.

What I also understood even back then was that we were going to live in the land of the enemy, the West. This mythical, unwavering ally to Israel, the land that hated us Arabs, us Palestinians — but paradoxically the only place that gave us a chance at the citizenship that we were denied in our part of the world. Even as a child I understood this, that we were going to a place that could be hostile to us. I was surprised to see that, when I told children and even adults that I came from Jordan, their reactions were confused. They had no idea where or what Jordan was, or who the Palestinians were. They’d often joke that the only Jordan they knew was Michael Jordan. My eight-year-old brain couldn’t fathom it. How could they not know?

I was in my grade ten French class when we heard about a plane flying into a building in New York City. The whole school was abuzz and our teacher, Mme Reid, didn’t bother teaching a lesson that day — the news of a terrorist attack in North America made it hard to go on with business as usual. I resented that such tragedies in countries outside the West — often much worse in magnitude — never elicited this kind of concern from most Westerners. Despite this, I seemed to be the only student concerned enough to ask Mme Reid to use our only class computer to keep up with the minute-by-minute updates — my childhood conditioning of plugging into the news in moments of tragedy had been immediately activated.

I still remember how much misinformation and speculation was being reported early on; any tidbit of information was regurgitated without fact-checking, the flow of information reflected the tragedy itself: intense, fast-paced, chaotic. It didn’t take long for news outlets to point the finger at Palestinian “terrorists.” CNN even aired old footage of a Palestinian wedding celebration and falsely claimed that they were rejoicing at the death of Americans. Fake news reports aside, I scoffed at the implication. These reporters understood nothing about Palestinians if they believed that any of our resistance factions had the resources, let alone the capability, to orchestrate such a thing in the US. And if they did, they would surely use them solely against their Zionist occupiers.

I reported to Mme Reid what I had read and it led us to an uncomfortable conversation about “terrorism.” I argued that it was important to understand why people did things like this in the first place. “So you think it’s justified?” she asked. No, I couldn’t justify it. She pushed on: “Do you think it’s okay for someone to strap a bomb to their body and kill innocent people?” I was stunned into silence. It enraged me that she would use that very specific example to illustrate her point, but I had not yet learned how to navigate this as a Palestinian. I had not yet perfected the dance. I didn’t yet know how to explain to my Jewish teacher that Palestinian resistance isn’t terrorism, or why generations of cruelty and injustice might lead someone to strap a bomb to their body and end their own life, and how this had nothing to do with Islamic fundamentalism. A palpable tension remained between us for the rest of that school year.

I eventually grew to resent this insidious discomfort that Palestinians experienced everywhere we went. The specter of Zionism was relentlessly at our backs, and we had to suffer silently while corporate news outlets happily regurgitated Israeli propaganda and vilified our struggle. Resistance from my vantage point in the diaspora was going to have to be different. I began understanding why it was so important to take control of my narrative — our narrative — and be part of the legacy of people fearlessly advocating for our freedom.

What radicalizes a Palestinian more than the mere fact of being Palestinian? Injustice is born alongside every one of our children. We grow up watching news footage of weeping mothers who sound just like our own, their bodies draped over corpses of murdered children who could have been us but by some morbid luck, weren’t. And through this we learn that the world will allow this because of who we are, and that the political powers have aligned themselves with our Zionist oppressors — ensuring and perpetuating hostility to our existence and our resistance. As such, they can never be trusted as so-called “honest brokers” of anything, let alone “peace.” The question should be, what doesn’t radicalize a Palestinian?

There was a moment in my formative years when I decided to be nothing less than unapologetically Palestinian — that I would never stop talking about Palestine. So when I picked up a microphone to perform my first ever stand-up set, I understood that having a platform meant owning the responsibility of spreading awareness about our cause. Every one of us knows that having any sort of platform is almost certain to draw the ire of Zionism’s lackeys, who seem to lurk anywhere a Palestinian happens to be. Which means that Palestinians in the public eye have all experienced some form of censorship or hostility as a direct result of their ethnicity. I’ve learned of several instances of this in the last month alone: A Palestinian friend and filmmaker’s latest project was edited against her wishes to remove Palestinian iconography, while another friend was doxxed for her pro-Palestine social media posts. I was recently given the opportunity to record a comedy album for a well-known production company. While pleased with the news, I was surprised that I was being given such an opportunity when I pulled no punches at calling out Israel’s genocidal tendencies in my routine. To no Palestinian’s surprise, the final version of the album was conveniently edited to remove all of my jokes on the topic.

I’m not the Palestinian you see on the news. You will not see me in a balaclava and an AK-47 in my hand, nor will you see my murdered corpse left to rot on the streets of Jenin or Hebron. I’m not the human rights lawyer carefully and articulately doing the newsroom dance, or the student activist risking their future prospects by confronting the powerful systems invested in Palestinian suffering. But still, I’m one of the millions of Palestinians around the world whose life is intricately woven into the web. In each one of us you will find the Palestinian heart; the liberated land itself. A fortified, untouchable place where we all find one another — exile and jail cells and refugee camps be damned. Until we’re back in that land, it is our dispossession that acts as the wellspring of our steadfastness, our survival, and our resistance. And because we are deemed to belong to “nowhere,” we — and thus Palestine — are everywhere. We stand firmly in every corner of the world with our hands joined together, organizing and laboring for our cause in the streets, in universities, and on Parliament Hill. What I’m certain of now is that Israel’s settler-colonial enterprise, when confronted with the Palestinian heart — even with billions in military aid and support from the most powerful institutions known to history —is rendered as helpless as an insect on its back. When I hear outsiders using the right words when talking about Palestine — apartheid, occupation, ethnic cleansing — I know we are heralding a new era in our struggle. All those times when I heard my grandmother, mother, father, aunts, and uncles utter the phrase within our lifetime, I thought I believed it. Today, I know I do.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)