American artist Michael Rakowitz (b. 1973) grew up in an Iraqi family in New York, and lives and works in Chicago. Across two decades, his practice has focused on highlighting the invisibility of Iraqis beyond images of conflict, either through food, archaeological artifacts or other narratives. In “Réapparitions,” on view from February 25 to June 12, 2022 at FRAC in France, the artist recreates or “re-appears” the missing and destroyed artifacts taken from the National Museum of Iraq after the American invasion in the early 2000s.

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

The sights on the ferry from Karaköy to Fener, the historical Greek district, a quarter midway up the Golden Horn, between Istanbul’s historical peninsula and the district of Eyüp, is something to behold: At dusk the orange skies of the city cast a shadow of fire over the undulating waters, populated by flocks of seagulls carefully tiptoeing on the striation of the current. Right off the Bosporus strait, the opulent vistas from the inlet allow you to consume history in blocks, from the protruding dome of the 6th century Hagia Sophia, to the unfinished luxury apartments rising unceremoniously at the edge of the shipyards on the opposite side of the promenade. There’s something alluring about this horizontal stratigraphy. Approaching Balat, the skyline resembles a stack of cake slices (as the wooden mansions of the area are known in the local architectural slang): Colorful multi-story houses painted in vibrant pastel colors form the picturesque facade of a lukewarm present, easily digestible and adorned with churches and palazzos.

Upon closer inspection, however, when you arrive on the mainland, the intentional time warp rapidly evaporates: Many of the painted houses are carcasses, and in fact just facades—they’re abandoned empty shells, derelict inside. These ghost dwellings are painted outwardly in order to give the illusion of ordinary life that is so treasured by the contemporary tourist. A billboard erected by the municipality celebrates the accomplishment of keeping alive this early modern heritage. But only a few blocks ahead, off the main streets, most of the houses are slowly crumbling or waiting to be sold en masse. Demolitions are frequent, and as these fragile ghosts quickly disappear, the empty plots reveal that the adjoining houses are also abandoned, rotting corpses. Yet the history of Fener is more than a catalog of ruins: After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, it became home to many Greeks from the city, giving rise to the demonym Phanariotes, a wealthy merchant class who occupied important positions in the Ottoman Empire.

Even though Fener is the traditional seat of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, the Greek presence in the neighborhood is so faint today that in spite of the grand metaphor of tourism, nothing is immediately visible — it needs to be forcefully excavated. It’s not that nothing remains, but that everything has become so disfigured as to become ungraspable. But the thinning past isn’t a Greek copyright: Once upon a time the Jewish Quarter of Istanbul, the larger Balat district, was home to a cosmopolitan population, including also Armenians. Minority populations were forced to leave as a result of riots, genocide and expulsions throughout the 20th century. Today touristy cafes coexist with synagogues guarded behind barbed wire fences. The kind of “thanatourism” (“dark tourism” involving travel to places historically associated with death and tragedy) surrounding Fener is of a particular kind, since the objects of historical consumption are not readily available, or obvious to the onlooker; they shine in their absence.

‘These are place holders for human lives that cannot be reconstructed and are still looking for sanctuary.’ In an era of global strife, with homeless people wandering around the world, we wonder often about the ancient notions of sanctuary and hospitality, sacrosanct in our traditions, and yet so far from our political reality.

With one grand exception. A friend writes to me: “Uniquely weird place with the usual Galata heteroclite architecture, scrunched together horizontally and also piled vertically, with that 19th century ghost school floating on top, ever-present, like some apparition.” He refers to the Phanar Greek Orthodox College, originally founded in 1454 by Patriarch Gennadius II, the oldest and most prestigious Greek school in Istanbul, housed now in an iconic red castle going back to 1881, designed by Konstandinos Dimadis. The school has weathered out all the expulsions and displacements of the country’s Greek population, and though its future is uncertain, it remains indeed an apparition, a ghost in the flesh, perched atop a hill.

There exists a sense of continuity between the grand monumentality of the building and the difficulty in locating the actual context and content of the surrounding ruin — they’re complementary. But how does one make an apparition gain depth or resurface when its meaning has become obscured? On the opposite direction of the ferry journey, from Fener to Karaköy, another mental archipelago of unmet tourist fantasies, we begin to unveil apparitions from a distant past, as a paradigm for the kind of historiographical practice that we wish to deploy when faced with the physical extinction of cultural memory combined with architectural grandeur, as we witness in Istanbul’s Balat neighborhood.

In his project, “The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist,” a small section of which was on show at the end of last year at Karaköy’s Pi Artworks, Michael Rakowitz began to recreate the missing and destroyed artifacts taken from the National Museum of Iraq after the American invasion in the early 2000s.

The task is of course unattainable as there are more than 7,000 artifacts, and so far, Rakowitz and his team have recreated about 900 of them. (The artist has always been careful to name all the members in his team, in order to highlight the obscurity of labor in contemporary art, which resonates with the archaeological context where it is indeed unnamed laborers who undertake the task of excavation.)

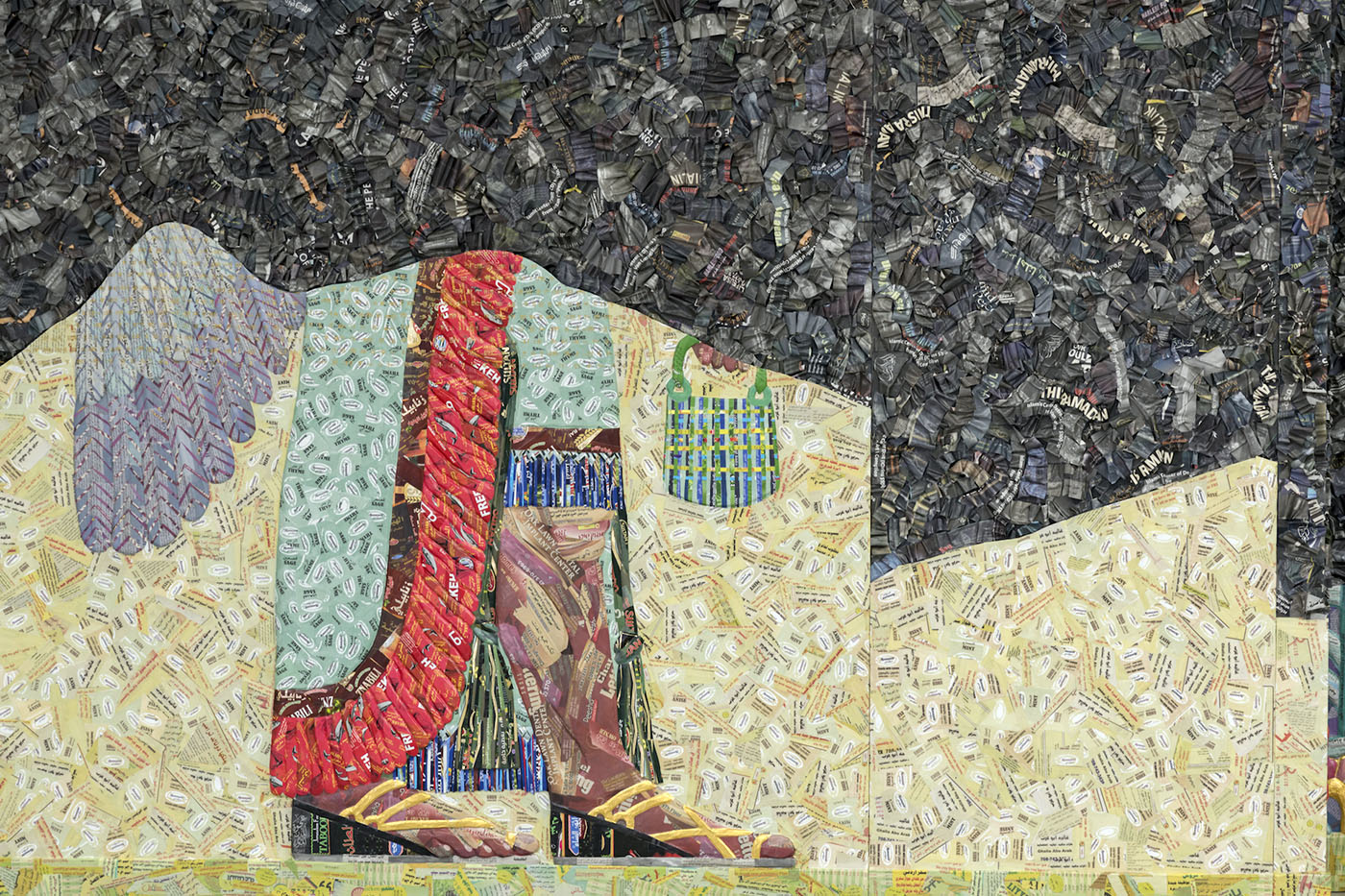

But to use the term recreating is misleading here, for what we’re dealing with is not an archeological restoration or reconstruction that aims to replace the past with a semblance, but what Rakowitz call re-presencing or re-appearing: For the artist these are not reconstructions or replicas, but reappearances. In this spectral, and yet wildly colorful form (making reference to the archeological debate on polychromy), these are ghosts that represent the lost Iraqis. In his 2021 lecture at the Oriental Institute in Chicago, (G)Hosting, Rakowitz uses a beautiful metaphor: “These are place holders for human lives that cannot be reconstructed and are still looking for sanctuary.” In an era of global strife, with homeless people wandering around the world, we wonder often about the ancient notions of sanctuary and hospitality, sacrosanct in our traditions, and yet so far from our political reality.

A number of Michael Rakowitz’s (re)apparitions of objects from the National Museum reveal themselves in Istanbul modestly laid on a table, and yet they establish a dialogue with us from an unreachable time—a time of destitution and powerlessness, not accessible from our two-dimensional present. As ghosts, they occupy an intermediate in-between where they’ve died but remain unburied, missing and restless. They are systematically documented in the exhibition in the manner of an archaeological display: “Museum number: Unknown. Excavation number: Kh. I 226. Provenience: Khafaje. Dimension(s) (in cm): 21 x 19 cm. Material: Bituminous stone. Date: Early Dynastic II (ca. 2600 BC). Description: Fragment of relief plaque, formerly inlaid (inlays missing); lower part shows outlines of two boats with rudders. Status: Unknown.” The clinical operation at work in museum accession cards is replicated almost entirely by Rakowitz and his team, even though we are dealing here with objects made of cardboard, food packaging, newspapers, and glue.

These new labels, however, instead of providing links to the existing scholarship (as museums customarily would do), relay quotes as fragments of conversations between the different layers of the past, creating extended knowledge networks between archeologists, artists, politicians, collectors and the like: “Our archeological heritage is a nonrenewable resource. When a part is destroyed that part is lost forever” (Usam Ghaiden and Anna Paolin). “Chapters in our understanding of human development will never be rewritten” (Micah Garen and Marie-Hélène Carletoni). “Let me say one other thing. The images you are seeing on television you are seeing over, and over, and over, and it’s the same picture of some person walking out of some building with a vase, and you see it 20 times, and you think, My goodness, were there that many vases? (Laughter) Is it possible that there were that many vases in the whole country?” (Donald Rumsfeld). It is an allegorical conversation about the meaning and value of heritage.

A more ambitious part of the project begins in 2015, following the destruction wrought by the Islamic State on Iraqi antiquities, when Rakowitz sets out to re-presence what was destroyed, which catapulted his practice to an entirely new level of intersectional conversations with the violent past of archeology and colonialism in the region. Many have seen the famous Lamassu that was unveiled in 2018 on the fourth plinth of Trafalgar Square in London (made out of cans of date syrup) as a public art commission; an Assyrian protective deity in the shape of a winged bull, guarding the Nergal Gate of Nineveh, near Mosul, from 700 BC until it was destroyed in 2015 by ISIS. Rakowitz is keen to remark in his Chicago lecture that the London monument, as a “place-holder,” is not only a ghost of the original, hoping to return in the future, but it also sits in judgment, between the institutions that hold Iraqi antiquities taken during the colonial era and the institutions that made the decision to invade Iraq in the 2000s.

And the real power of these ghosts is only unleashed when Rakowitz turns his attention toward a royal palace in Nimrud, known as Kalhu in Arabic, some thirty kilometers south of Mosul. The Northwest Palace, inaugurated around 879 BC, under King Ashurnasirpal II of Assyria, a brutal ruler, amassing spectacular wealth, and embarking on an expansion campaign from the Asia Minor to Syria. The destruction of the palace during ISIS occupation of Mosul is so extensive that it is estimated over 60% of the excavated area is lost beyond repair. According to US media at the time: “Several videos released by the militants last year show ISIS fighters using sledgehammers, power tools, and bulldozers to demolish priceless sculptures and stone carvings. What they didn’t destroy with explosives they tore down by hand.” The palace is a humongous structure, on the east bank of the Tigris River, covering 28,000 square meters, designed around three or four lavishly decorated courtyards.

But when ISIS entered the site in 2015, it wasn’t anything like a fresh ruin—the ruin is an ideological production. Archeologists had extensively excavated the site since it was rediscovered by Austen Henry Layard in the 1840s. Subsequent excavations by British, Polish, Italian and Iraqi archeologists, as well as by opportunist looters, have scattered the contents of the palace to all the corners of the earth—there’s material from Nimrud in museums in 20 countries, the vast majority in Britain and the United States.

Rakowitz and his studio have reappeared 7 rooms from Kalhu: N, G, Z, H, sections from rooms F and S, and section 1 of room C that was on show in Istanbul. Following their signature method, working on relief sculptures on wood panels, the team has created the colorful reliefs from newspapers and food packaging, leaving out in dark shades the parts of the relief that were already missing.

One of the most interesting curatorial strategies in the project is leaving out the looted reliefs which are now imprisoned souls in colonial institutions (an expression I learnt from the late Peruvian artist Juan Javier Salazar) in the West. These empty spaces carry weight turned upside down. In the Istanbul exhibition, three of those blank spaces are visible: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Vorderasiatisches Museum and the Istanbul Archeological Museums; a fourth relief, C-10, almost entirely destroyed, is reappeared, and belongs to the National Museum of Iraq—7 other fragments from the room are displayed in other museums, as we learn from existing scholarship.

The empty space left for the entire slab kept at the Istanbul Archeological Museums, C11, hits home, and makes us wonder, why would there be a blank space for a regional museum, in the heart of the Middle East, amongst the Western colonial institutions? The history of the museum, one of the first colonial museums in the world, alongside the Louvre and the Metropolitan, deserves attention on its own: Founded in 1891, as the Ottoman Imperial Museum by Osman Hamdi Bey, it amassed a great collection due to an imperial decree protecting cultural goods in the Ottoman Empire. Governors from all the provinces would send in artifacts to the capital city, in what amounts to cultural extraction from all the peoples of the vast Ottoman state.

But this would be a simplification of an extraordinarily turbulent era, replete with administrative chaos, networks of local spies, foreign diggers, licensed expeditions, incomplete inventories and personal loot that facilitated the rapid extraction of antiquities from the Ottoman lands in the 19th century. The history of the Ottoman Imperial Museum is a riveting account of an era when the question of who owns antiquity was asked constantly: In 1883, while the museum was under development, French archeologist Salomon Reinach published a paper questioning whether Turks should be permitted to own antiquities belonging to the classical past of Europe, and a proposal was launched to acquire all the antiquities in Istanbul, and in exchange, present the Ottoman state with a large assortment of gifts, consisting of pieces of Turkic art (such as swords, miniatures, pottery and carpets), scattered all over the world, to form a national museum of Turkish art.

Rakowitz has always been aware of the invisibility of Iraqis to the American public except as combatants and dead bodies presented in high definition sound and images on TV. Similarly, minorities in Istanbul, now and in the past, are often only presented as deviants, criminals and outlaws.

In February, Rakowitz will open the exhibition “Réapparitions” at FRAC Lorraine, in France, with reliefs from room G of Northwest Palace, a much larger room, also excavated by Layard in 1846. 12 museums and an anonymous private collector have kept different parts of the room, alongside over 16 missing fragments and an astonishing 28 remaining fragments in situ, now presumably destroyed. The Istanbul Archeological Museums appear again, with 3 different fragments, confirming their place of honor among the loot museums of the world.

But there remains a key to unlock in the constitution of Rakowitz’s re-apparitions that will soon link them to the disapparitions of Istanbul’s Fener: The food packagings used in the sculptures (all of them their real size), are coming from the colorful wrappings, boxes and cans of Middle Eastern foods available in American supermarkets, and in the eyes of Rakowitz, a way in which peoples have bypassed sanctions and closed borders to reappear in another geography (Arab newspapers from Chicago and other American cities have been also used). It all started with cans of date syrup produced in Iraq but labeled in Lebanon, and later on, in the Netherlands.

The intimate and crucial relationship in Rakowitz’s work between food and reappearances, as embodied in his earlier project “Enemy Kitchen”, turning around a narrative of opacity to make Iraqi cuisine visible to an American audience, allows you to think through a subterranean layer of visual and sensorial memory, hidden behind the hollow facades of Fener: Beyond the thin strip of dilapidated modernist houses facing the sea, past Phanar College, a working class neighborhood starts uphill, leading up to the Faith Mosque, built in 1463, by the Greek architect Sinan-ı Atik, on the edges of which, on a pedestrian alley, a Syrian market, casually grows. Since the beginning of the ongoing conflict in 2011, Syrians have settled around there and enacted something like a new life: It is not the reproduction of a Syrian city, but rather the production of an exile, of a rupture, of a temporal temporality.

It’s not only the smells familiar to Levantines—pungent garlic sauce, cardamom and orange blossom, but also the reappearance of a popular visual culture in the manner of Rakowitz: Traditional colorful food packagings from Syria and Lebanon are reproduced in exact resemblance of the original with Arabic fonts, except that the contents are brought unmarked into Turkey from Syria, and then packaged here as “Made in Turkey”. Are these re-apparitions place-holders for the lost lives as well as reconstructions of something else? Place-holding in a place like Istanbul works in two directions: Not only do they stand in place for those who are immediately missing and are now displaced, but are place-holders for those who were displaced before them.

When I spoke of temporal temporality, I also referred to the precariousness of their presence in Istanbul: Toxic nationalism and cycles of propaganda and economic stress, return to haunt migrants and local minorities in Turkey, generation after generation, usually in the same cosmopolitan locations, constantly threatened with the possibility of pogroms, expulsions and violence. So when Michael Rakowitz states that the invisible enemy shouldn’t exist, we wonder, who is the enemy or the friend here? Rakowitz has always been aware of the invisibility of Iraqis to the American public except as combatants and dead bodies presented in high definition sound and images on TV. Similarly, minorities in Istanbul, now and in the past, are often only presented as deviants, criminals and outlaws.

In his seminal text “Politics of Friendship,” Jacques Derrida tells us that the political as such wouldn’t exist without the enemy and without war, and that losing the enemy would mean to lose the political itself. Thus he concludes that according to the classical paradigms of politics, the enemy, often unknown, has to be made public, because the sphere of the public emerges only with the figure of the enemy. And he asks a question which would be familiar to Michael Rakowitz: What about deriving politics from friendship and not from enmity?

Derrida refers to the question of friendship over enmity, as a memory site that connects history with lived experience: “Friendship is never a given in the present; it belongs to the experience of waiting, of promise or engagement. Its discourse is that of prayer, and at stake there is what responsibility opens to the future.” The presence of Rakowitz’s re-apparitions in Istanbul, against the background of their uncanny archeological violence, was a borderline form of temporariness (the gallery space has already moved elsewhere, a regular occurrence in the fluid human geography of Istanbul, removing the context of the re-apparitions from a physical place), but these ghosts bereft of sanctuary, remain in conversation with the local specters, waiting to reappear in whichever form they can. Rakowitz’s crucial emphasis is on the lost lives and communities that ultimately will never be reconstructed, and in lieu of which no artifact can stand.

Who is the host here and who is the ghost? And can ghosts offer a space of hospitality to their own temporary hosts? Could this hospitality be translated into the permanence of temporality? In his exhibitions throughout the world, Rakowitz has invited communities of Iraqi diaspora to host their own Western hosts, in these contexts always going around the theme of the re-apparition of the past in the fragmented present. The lasting problem with the ghost for the host, as I wrote elsewhere, is that as Derrida points out, the ghost cannot even be called a being because it doesn’t exist—it is both present and non-existent, and therefore one cannot enter into mourning with ghosts, because ghosts never die, they always keep coming back…

But what if the relationship between the ghost and the present could be transformed into a transtemporal friendship, and not a forced cyclical repetition of a violent past? Without a corpse and a burial, no closure or mourning is ever possible. Rakowitz’s apparitions hold the place of others who perished at sea or in war or in dangerous crossings, and who can no longer speak to us, in the same way that objects from the past do not speak—it is us who articulate these grand narratives. Broken and wingless, the silence of the Assyrian ghost confronts us, but this confrontation doesn’t have to be fearful; it’s a moment of joy, the joy of mutual recognition, of survival, across impassable boundaries.

Michael Rakowitz’s “The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist — Section 1, Room C, Northwest Palace” was on view at PiArtworks, Istanbul, October 28-December 25, 2021.

“Réapparitions” will be on view at FRAC Lorraine, Metz, February 15-June 12, 2022. Rakowitz’s exhibition “Nimrud,” at the Wellin Museum, in Clinton, NY, October 19, 2020-June 18, 2021, was shortlisted as one of the best exhibitions of 2021 in the United States by Hyperallergic.