In this short story translated from Persian, an ordinary day swiftly — and brutally — changes course, with lasting implications.

She lingered at the threshold of the entrance to the building, uneasily shifting the groceries in one hand while holding onto the sleeping child with the other. Another half step inside and she could hear tentative steps behind her. She turned. Her daughter, in school uniform, was gazing at her with a fearful look that Tahmina hadn’t time just then to question.

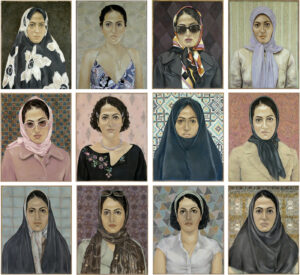

“Hurry,” she called to the girl. “Come take your little brother off my hands.” She loosened the tight hold she had on her chador so she could hand over the boy.

Masume managed a weak salaam before taking the boy from her mother. “Maman,” she mumbled meekly.

But Tahmina was already hurrying down the hallway. Everything in her body ached today. The groceries seemed to double in weight the closer she got to the apartment. But then something in what she’d noticed in her daughter’s face made her slow down. She hesitated and turned, “Where’s your brother? Where’s Alireza?”

The girl uttered another “Maman,” and then burst into tears. “Alireza didn’t come for me after his school. They say he went to fight the big boys in fifth grade.”

Tahmina set the groceries down. Her back was throbbing. The outside light of December leaking into the building was weak and made the hallway feel more claustrophobic than ever.

“Fight? Fight over what? That boy never fought in his life. What are you saying?”

The girl was crying again.

The mother closed her eyes for a second and took a long, deep breath: “Ya Imam Reza, give me the strength!”

In a minute she had hastily left the groceries in the apartment, told the girl to stay put with the child, and was off running. Running because she knew people like them never got a second chance. Running because what if her eldest ended up being expelled from that school? What then? Every day she offered thanks for the little they did have, even if all they had was a damp little basement apartment in the Abouzar district, where most days she cheated their meatless dishes with mounds of potato and tomato paste. She gave thanks that her family had escaped the war way back when and managed to eventually make it to Tehran. It didn’t matter that more wars had been her lot ever since — war to marry the man she loved, war to hold onto him, war to not get kicked out of this latest hole-in-the-wall apartment, war to not have to go back to their own war-torn province where nothing had been fixed and no one had been compensated for losing their lives and livelihood. The battles were relentless. Another inheritance, she supposed, from her luckless father who had caught stray shrapnel one day, the metal piercing the old man’s thigh and making him housebound. By then it didn’t even matter. The family farm back home was already gone. Gone with the evil harvest of a thousand land mines that would stay under that earth for years and years.

So Tahmina ran. She could not remember a time she hadn’t been running.

She sprinted across the schoolyard while the old watchman ran after her yelling weakly for her to stop. Soon she was panting in front of the school principal’s desk who demanded to know why she had barged into her office like that.

“Fifth graders mean to fight my son.”

The principal gaped at Tahmina. A hard cold wind slammed the office door and the old watchman wobbled back to his post at the school gate, cursing under his breath.

After several phone calls to the homes of Alireza’s classmates, it turned out the boy had stood up for a friend who was being bullied by the older fifth graders. That was when they’d turned on Alireza, calling him the son of a stinking orderly who had to clean after the piss and shit of old people at the local hospital. Fighting words. The boy had to defend his father’s honor. A place had been set for the fight after school. The meydan up the road near the power relay station.

Tahmina was running again. This time the principal, an asthmatic middle-aged woman with a permanently startled look, stumbled after her.

Halfway to the meydan, she felt her body defying her. Everything hurt. Her head. The cramps in her stomach. The nausea. If only Vahid were here. Twelve years ago it was Vahid who had been taking care of her father at the hospital. The best male nurse in the world. The best nurse period. The best husband. And not just because he too was a refugee from down south in Ilam like them. Vahid was someone you grew to love more and more every day. Reliable men were not something you could find just anywhere. Even her mother who had at first been against their marriage said so.

On seeing Tahmina and the principal, the fifth graders leapt off Alireza’s bloodstained face like a pack of jackals and ran away. The boy stood up casually, dusted himself off, and let his mother take him into her embrace. She was self-conscious. This was exactly how she had held her father for the very last time, wiping the sweat off his forehead and praying that this would be his final convulsion. Her prayer had been answered.

In the evening, as soon as Vahid arrived from work, the family was there as always to greet him at the door. Except for Alireza who lingered in the back.

The father looked at the boy and at Tahmina questioningly, “What’s wrong with the boy?”

“He’ll tell you himself.”

At dinner the boy had to struggle through the stitches above his lip to tell what had happened that day and why. Tahmina watched as the kid, on the verge of tears more than once, held himself together and finished his story. She was proud of the boy — how he’d stood up for his father’s name, even if it meant a bloodied face. And she could see in Vahid’s eyes too the same unhappy satisfaction.

The vat of cooking oil she’d brought home that day from the market sat next to Vahid. He had just punctured it open for her with their one good kitchen knife, but the tip of the knife had broken. She made a mental note to have the thing sharpened tomorrow. Vahid was telling Alireza he’d done right to support his classmate. Tomorrow they’d go to school and have things sorted out. Those fifth graders had no right to be bullying the younger children like that. And if the school couldn’t handle them, then they’d put in a complaint at the local precinct.

The next morning, the principal was defensive at first. “You have to admit that your son too is to blame. Not only did he fight those fifth graders, he even broke the mobile phone belonging to one of them.”

Tahmina watched and listened quietly while Vahid spoke. “First of all, those kids insulted my child and me. Second, there was a whole gang of them and my boy was alone by himself. Third, they are all older than Alireza. And fourth, aren’t mobile phones supposed to be banned at school?”

“Still, your son, Mr. Ahmadian, broke something expensive that wasn’t his.”

“Play with fire and you’ll get burned. Maybe it’s a lesson learned for that kid.”

The principal frowned. “Fair enough. I’m going to call in that boy. I admit he’s the one who started it. He is going to apologize. But your Alireza too has to promise he won’t fight again.”

Tahmina breathed a sigh of relief. Vahid had been calm but forceful. She hadn’t wanted Alireza to be here when they spoke to the principal, but now she wished he had been so he could watch and learn how his father dealt with a difficult situation. The principal had intimated that the fifth grader’s father worked for a well-to-do merchant at the bazaar and had left a threatening message late yesterday. Maybe the man had calmed down since then. Maybe for a change it wasn’t going to be about who had money and who didn’t and they could walk away this morning with justice served for everybody.

There was a knock and the kid came in. He had a black eye and right away on being told he had to apologize he burst out crying. Tahmina felt for him. She reached out for the boy, intending to caress him and tell him it would be all right, but the kid slapped her hand away, “My father is going to show all of you a lesson! Wait and see.”

The principal was exasperated. “Get out of here. Go back to your class.”

Vahid, who had been cooly smiling until a minute ago now looked stunned. “That kid needs a lesson. I’m going to go to the police station from here. Bullying lower graders and attacking my son after school with his gang.”

He signaled to Tahmina that it was time to leave. The principal stood behind her desk in her usual state of bafflement. “I promise you, Mr. Ahmadian, it wasn’t supposed to be this way. I will take care of the situation myself. None of this will happen again.”

“I hope so,” Vahid muttered under his breath. To Tahmina, he seemed subdued. The worst of it was over. The principal would take care of the rest like she’d promised.

Just then the door of the office was thrown wide open and in walked a uniform with another man in tow. The civilian was a paunchy man with beady eyes. He gawked at Tahmina and seemed to want to rip her head off.

“We were told Mr. Ahmadian is in here?” the policeman said.

Vahid hadn’t quite finished saying that yes, he was Mr. Ahmadian when beady eyes screamed, “Arrest this bastard right now! I told you he’s here.”

Tahmina watched her husband stand there in utter disbelief for the second time in as many minutes. Already she could guess what was happening.

The policeman held the other man back and addressed Vahid, “Mr. Ahmadian, a complaint has been lodged against you since yesterday. This gentleman’s son has been the subject of assault by your son. He has incurred damage and loss of property which you’ll have to address at the station.”

“Are you joking?”

The policeman stared at Vahid as if to say, Does this look like a joke to you?

Tahmina had to sit down. A dull pain seemed to grab hold of her entire body. Her head was on fire. She was dizzy. She lost track of what the men were saying. There was shouting which the principal could not contain. She heard parts of sentences but wasn’t able to put them together to make a whole of what was being said. In a minute that awful man and the policeman he had come with left the room. Had they been waiting here all along? She saw Vahid follow behind them, turning around at the last second to say something to Tahmina which she could not comprehend.

With all of them gone, the principal finally came over to Tahmina.

“Are you all right, Mrs. Ahmadian?”

Tahmina nodded. The room had stopped spinning. The principal offered her a drink of water, which she took.

“Where did my husband go? Where did those men come from? Did you call them? When did you call them? Why did you call them? How were they here so fast?”

She saw the concern on the principal’s face; the woman was speaking rapidly. Vahid had gone to work, the principal explained. But had to show up at the police station this afternoon. Mr. Jahani, the plaintiff, would be there too. Mr. Jahani worked for one of the biggest merchants at the main bazaar. The man had money. He helped the school quite a bit. “It would be best if your husband makes peace this afternoon and pays for the broken phone. And I promise you, I did not call Mr. Jahani here this morning.”

“But …”

Words seemed to collapse before they came out of her. Vahid would never submit to the likes of Jahani. There would be more trouble. They could barely make rent this month let alone pay for someone’s damaged phone. And what if they were forced to take Alireza out of this school? No, it wouldn’t do. She had to do this herself and she had to do it between now and this afternoon. A sharp pain shot through her inner thighs and around her hips. She hadn’t even told Vahid yet that she was pregnant again. She had forgotten. Or no, there hadn’t been time last night. Maybe there had been. She didn’t know. She didn’t know anything. She had to sharpen that broken knife. She’d do that after she visited this man, Mr. Jahani, at his place of work at the bazaar. She had meant to cook something special tonight. They were going to celebrate another addition to their family. But she didn’t remember what she was going to cook. She always had trouble deciding. A pain shot through her hips again.

She stood up with difficulty. “I will fix this. I promise.”

“But are you up to it, Mrs. Ahmadian? You look a little shaken.”

“I am fine. Please just give me the address of Mr. Jahani’s work if you have it.”

It had begun to rain hard. The bazaar was busy with shoppers and porters racing to get out of the downpour as fast as they could. It took her a while to find her bearings. The place was at the end of a long cul-de-sac where posters from the recent elections were beginning to bleed off the old walls from the torrent. The man she was looking for was Haj Sadri. She had expected someone older, but the long bearded man with the meticulously ironed white shirt buttoned to the top didn’t look a day over thirty. It was as if they all had been waiting for her. Jahani, the boy’s father, sat in one corner of the office and another man sat next to him.

By the time Tahmina had breathlessly said what she had to say she’d already apologized to Sadri and Jahani a half dozen times.

She finished, not looking at any of the men, and waited. She felt shame for even being here, among these men who were utter strangers, and without Vahid having a clue that she’d taken it upon herself to do this.

Sadri cleared his throat and addressed his employee. “Our sister here looks very upset. And she has every right. Two boys had a fight and there’s no reason to make such a big fuss about it. Come, Mr. Jahani. Let’s all go downstairs. I want you to write a note retracting your complaint. As for the cost of the phone, I’ll take care of that myself. No worries.”

Tahmina closed her eyes — Ya Imam Reza, thank you.

In a moment they were all downstairs. It looked like a cellar where they kept wholesale merchandise. No windows. No light coming in or out. Jahani and the other man stood to the back while Sadri shut the cellar door behind him. Her heart skipped. Why here? Why even a written note? The plaintiff always had to show up in person to withdraw a complaint. A letter meant nothing. None of it made sense. She’d been so relieved thinking she’d resolved the dispute that she hadn’t thought through any of this.

A hand reached for her from behind. It was Sadri. He brought his face, reeking of stale cigarette smoke, close to hers. “Open your notebook and I’ll write a beautiful note for you myself.”

She stepped back only to feel the wall of the other two men blocking her retreat. One of them laughed. It was Jahani. The other man tried to pull Tahmina’s chador off. She screamed and snapped away from the two men only to end up face to face with Sadri again who leered at her. She was falling. Falling off the edge of the world it felt like. Her hand reached inside her handbag because she didn’t know what else to do. It was not rehearsed and she had not thought of it until the moment she felt the orange handle of the knife she’d meant to take to the knife sharpener today. Sadri took another half step and Tahmina stabbed him as hard as she could with the blade.

The man’s hideous scream echoed through the cellar and he fell to the floor holding his side. Her own screams were that of a wounded animal. All she knew was that Jahani was now coming at her and she raised the knife as high as she could to strike again. Jahani retreated. They watched her, in fear and astonishment as she never once let up screaming while running upstairs and out into the alleyway.

She had lost one of her shoes. She took the other one off to move faster through the muck of the drenched streets. At the bus station, people stared at her, shoeless and panting. She eased her chador further down to cover her feet.

She sat leaning her head on the metal pole of the bus. Exhausted. Every part of her body seemed to be revolting against her. Her nausea returned. It felt as if the hands of every stranger in this city had been touching her. She was disgusted. With the world. With herself. With the thought of the stink of Sadri’s mouth as he brought his face close to hers. The wind howled outside of the old bus and the rain didn’t let up. She stared at her torn socks, her big toe now sticking out of one of them. The end of yesterday evening had seemed so perfect. They were going to get justice today and she was going to tell Vahid that a fourth child was on the way. She’d gotten the test results back at last.

She stayed until the end of the line and waited until the only two people left got off. Her back pain made straightening up difficult. She turned to reach for her bag. A large red stain covered the surface area where she’d been sitting. Tahmina paused a moment, took a good look at that stain, ran a hand over her throbbing belly, and exited the bus.