Featured Artist

Nazanin Pouyandeh

This Franco-Iranian artist currently has several canvases featured in two major French shows, including Immortelle, “Vitality of Young French Figurative Painting,” from March 11-June 4, 2023 at MO.CO, 13 rue de la République, Montpellier, more info; and Femmes guerrières — Femmes en combat (Women Warriors, Women in Combat), through July 2, 2023, at the Labanque art space in Béthune (Pas-de-Calais), 44 Place Clémenceau, more info.

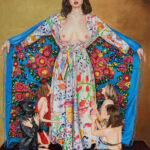

Born in Iran in 1981, the artist came to France when she was 18, fleeing oppression in Iran. She received a French grant to study art and got into the Beaux-Arts in Paris in 2000. At the time, she found an anti-figurative atmosphere, but remained “fascinated by pictorial power.” She began working with collages and then seguéd into painting hyperreal imagery. Nazanin Pouyandeh takes photographs of her friends and then paints onto large canvases (“I can’t have them standing around posing for days”). She recently described herself as a multilayered person with a complex identity. “I am a patchwork of several cultures; we all are…The notion of collage is also philosophical. We are all more or less créolisés these days.”

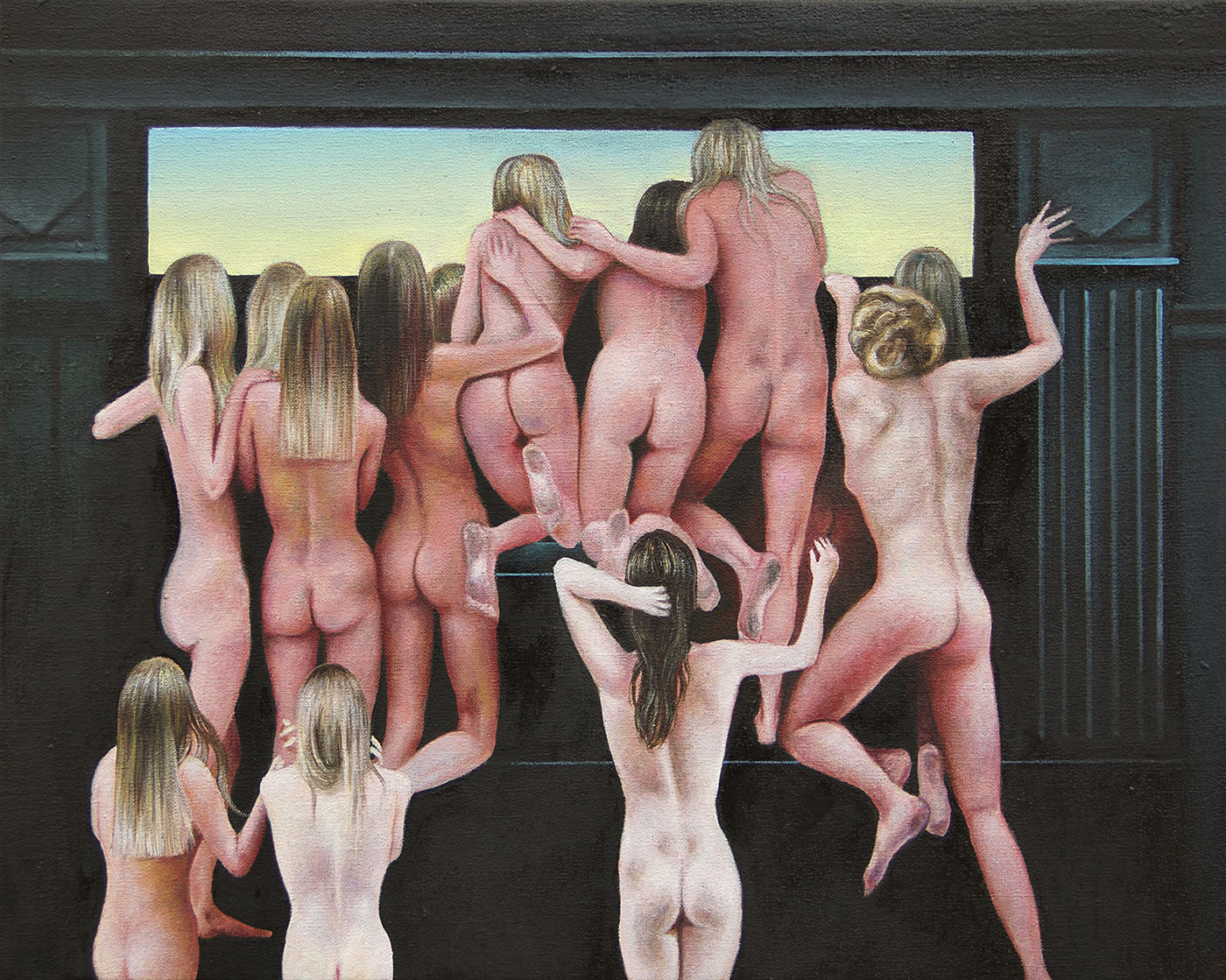

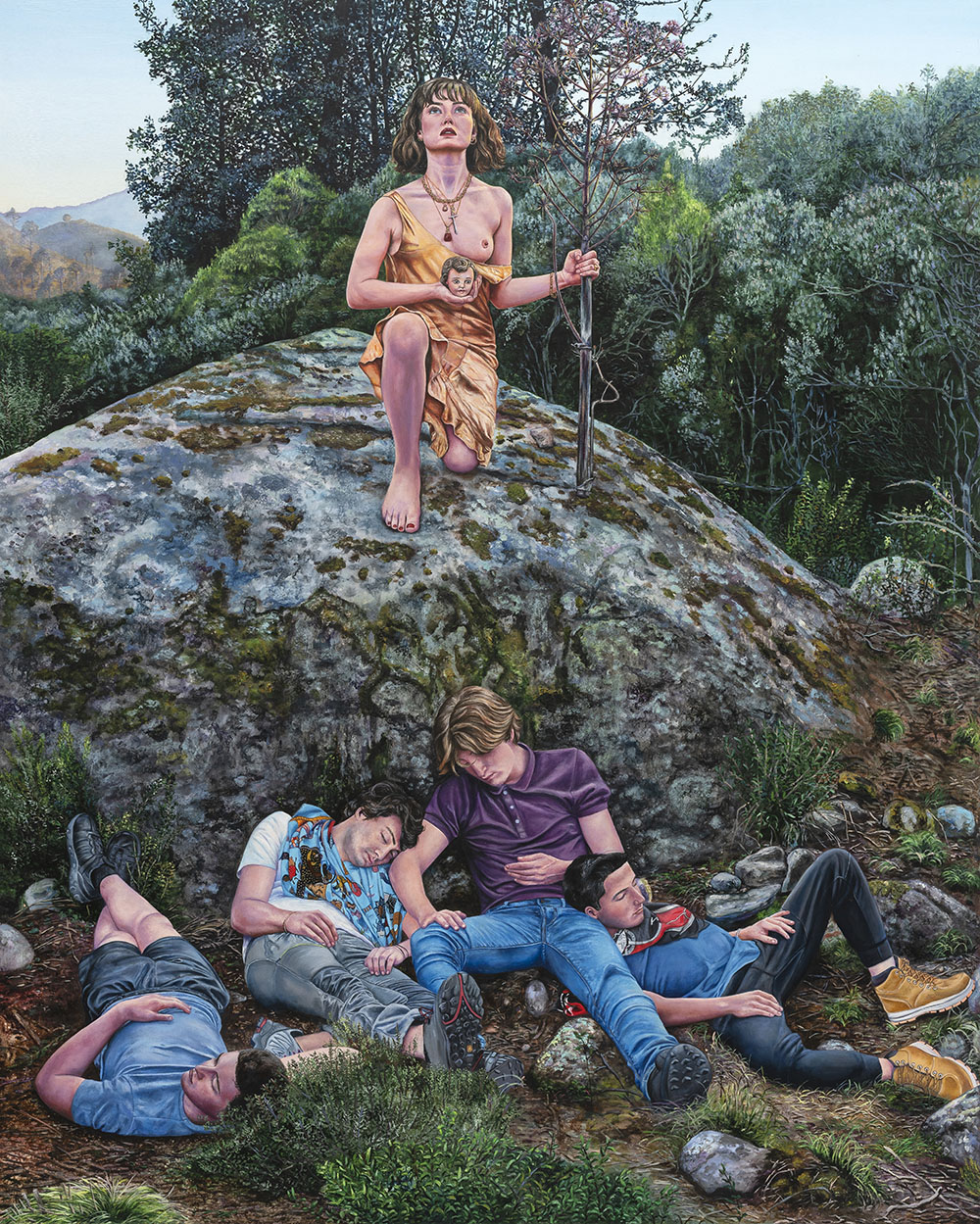

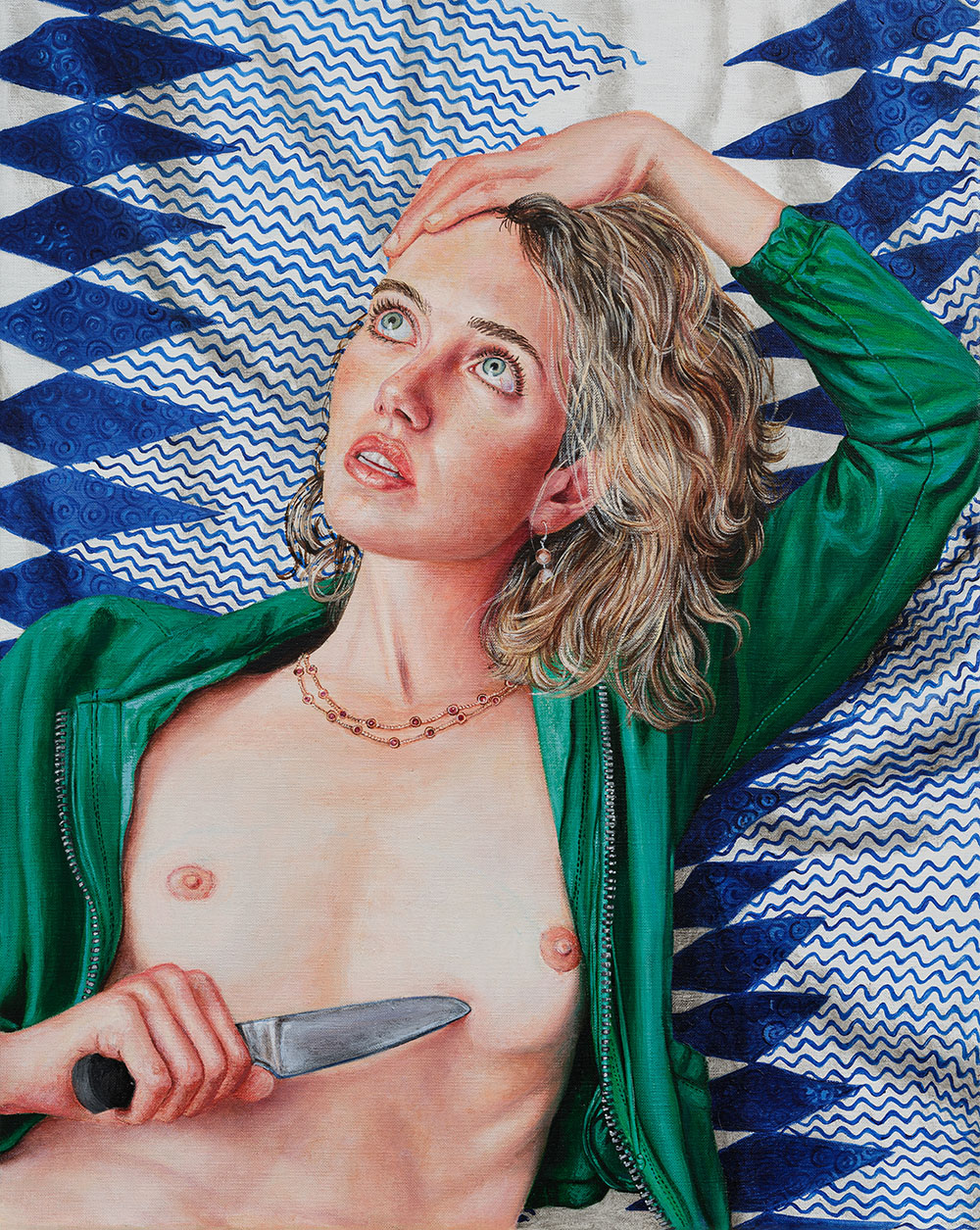

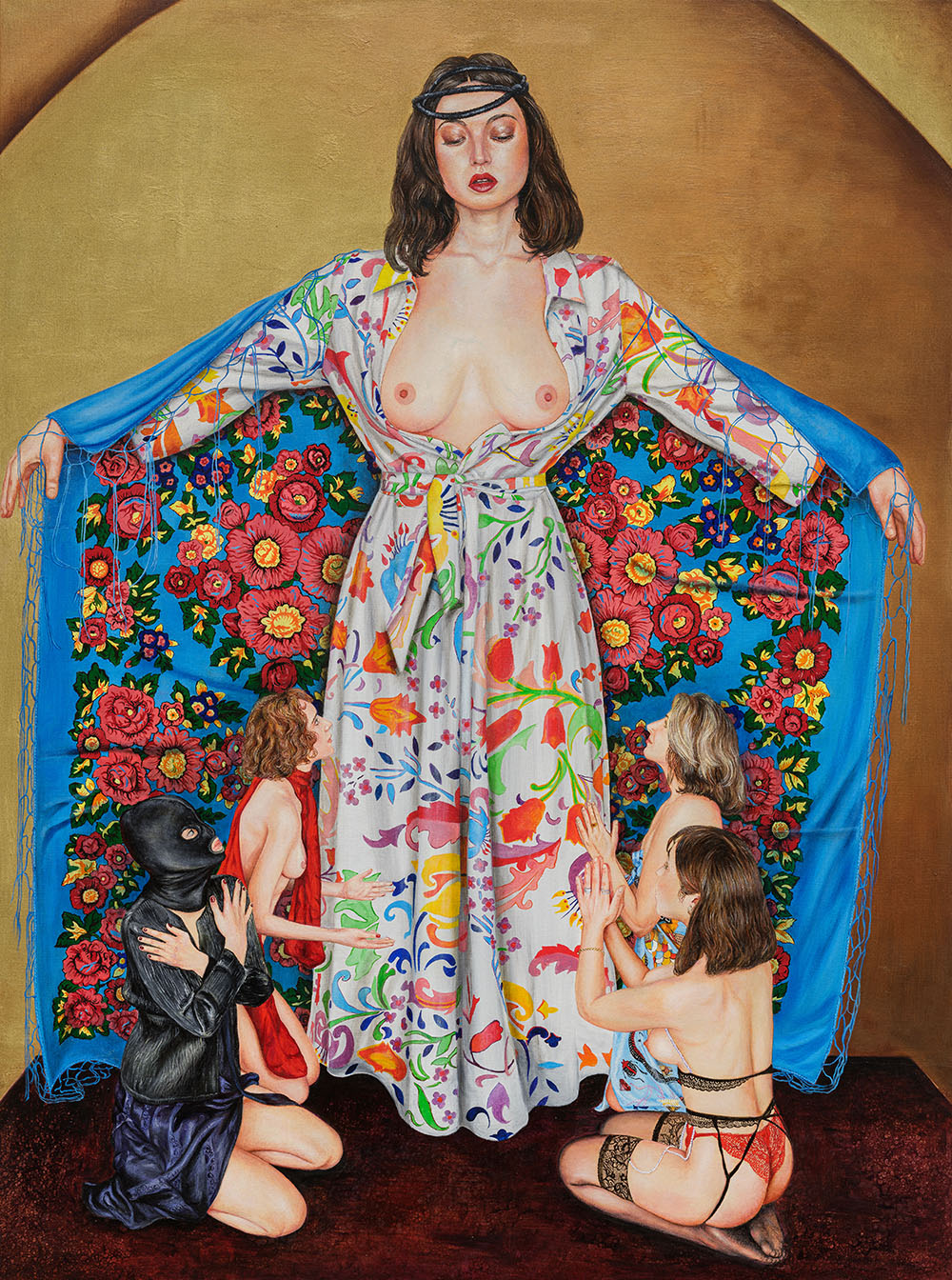

The following images are from her work included in Immortelle:

Nazanin Pouyandeh has made France her home, but continues to look back at the country of her birth. In October the painter published an op-ed in Le Monde, identifying with Iranians rising up against the regime in Tehran. “I join the young Iranian women who are protesting after the morality police murdered Mahsa Amini for incorrectly wearing her hijab. I am 41 years old. I have never known freedom for women in my country. ”

She also shared her personal story:

I fled to France in 1999, when I was 18, after the government murdered my father, Mohammad Jafar Pouyandeh, at the age of 44. He was a translator, writer and human rights activist. His execution was part of a series of assassinations of writers and intellectuals mandated by the Iranian secret service. My father devoted his short life to translating some 30 books and 100 articles on gender inequality and human rights from French into Persian. He thought they were part of an indispensable cultural and social evolution that would allow people to achieve freedom through awareness.

In the last years of his life, he was an active member of the Iranian Writers’ Association, which fought for freedom of expression. Because of his cultural and intellectual activities and his firm stance against censorship, my father was constantly interrogated and threatened by Iran’s intelligence services. His translation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was published a week after his assassination. His murderers went unpunished and some of them now hold important political positions in the Islamic Republic of Iran. His death is an open wound in the history of Iran and in my soul.

The following paintings are from her work in Femmes guerrières — Femmes en combat in Béthune: