Both Rotten Evidence and the trial against Naji are attempts to, in some ways, define literature and writing, or at least their fundamental purpose.

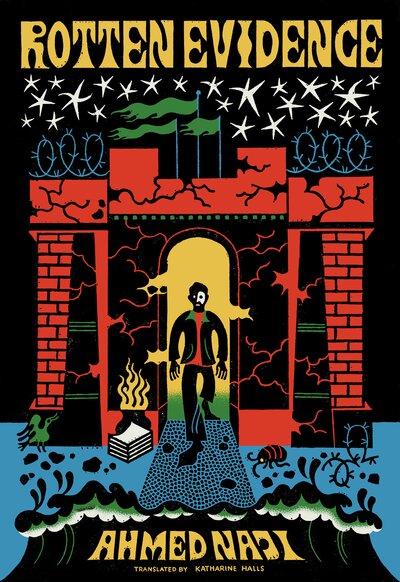

Rotten Evidence: Reading and Writing in an Egyptian Prison, by Ahmed Naji

McSweeneys 2023

ISBN 9781952119835

By now, the story has become the standard addendum following any introduction of Ahmed Naji’s name: in 2015, an excerpt from the young Egyptian writer’s second novel, Using Life, was published in a literary supplement in Cairo. A sixty-five year old man filed a case against Naji and his publisher, “alleging that reading the excerpt caused him to experience palpitations, sickness, and a drop in blood pressure.” While Naji and his publisher are ultimately acquitted, prosecutors then file an appeal, under the argument that Naji’s text “harmed public morals.” Naji is found guilty and sentenced to two years in prison. He spends ten months there before another appeal — from the defense — earns him a release.

Rotten Evidence is a non-linear account of those ten months, a combination of reading journal, dream diary and daily reflection. Originally published in Arabic in 2019 as Hirz mikamkim, Naji described, in a talk at City of Asylum, the unorthodox process of the translation, a collaborative work between himself, translator Katharine Halls and editor Daniel Gumbiner. Rather than striving for a “faithful” rendering of the Arabic original, the translation was treated, at Naji’s own urging, as an English text unto itself and edited as such, regardless of any departures that this necessitated from the original.

The book is not so much a prison memoir as the memoir of a time spent in prison. This is because Naji, from the very outset, engages earnestly with the idea of genre, highly aware of both its conventions and constraints. “Prison literature,” Naji tells us, “in the mind of the political prisoner, is an unavoidable feature of the political struggle […] an extension of their activism.” Moreover, it also necessitates writing about other prisoners, which Naji mostly avoids here, seeing it as an infringement of people’s privacy as well as, if one is not careful to render “the frustration and humiliation of prison without reducing its victims and their secrets to figures of drama,” a violation of the “relationship of obligation” imposed by the bonds that one ends up sharing with fellow prisoners.

But the real issue, he says, is that: “Most Arabic prison literature I’ve read isn’t concerned with ‘artistry.’” Its intention rather lies in “the documentary content of the text and what it can do to serve the literary-political cause.” But Naji declares himself “a writer who doesn’t give a fuck about history,” and as such declares his book an attempt not to write about prison, but to write about writing (and reading) in prison.

In tone, the book is cynical, bitterly funny, oftentimes tender without ever being sentimental, and Naji accomplishes all of this through a wry distance from all his subjects, including, first and foremost, himself.

This is a book about the self, the self as writer, about the self vs. society, which, if one is to speak broadly, is one of the essential themes of literature, and is a particularly relevant preoccupation for literature — and novelists — from the Arab world. It would be easy to fall into East/West dichotomies here, with the West as the place which champions the individual by way of holding sacred personal freedoms, and the East as the place where the individual must be subsumed into the conformity of the (inevitably) authoritarian society or else risk censure, imprisonment, or worse. But Naji rejects this easy framing, too. Among a list of cliché themes and subjects he bemoans, that he says he’s “tried so hard to run away from,” are: “Authenticity and modernity. Why the Arabs have lagged while others have flourished. Self and other, East and West.”

Perhaps, at the risk of generalizing, it can be said that Arab writers are more keenly aware of how their consciousness and choices have been shaped by social forces, domestic and political both. Whether they choose to write about social issues or relegate society to the background while foregrounding the individual, it is always a conscious decision, undertaken either to directly address or reject a particular template, literary and/or existential. And Naji falls firmly on the latter side, as evinced by his larger work in general and this book in specific.

Both the book and the trial against Naji (its absurdities hilariously sketched out here) are attempts to, in some ways, define literature and writing, or at least their fundamental purpose. And it should be said that Rotten Evidence is a definition of writing against the one offered by the trial, in which one judge, offering a ruling to justify the initial two-year prison sentence handed down, “arrogantly attempt[s] to define anew the craft of novel writing.” Set out as one in which the writer “extends a call to virtuous acts, to the adornment of the self with good morals, and to the performance of commendable deeds” — all of which, says the judge, endow the writer with a role no less than that of “the tongue of society, truthfully expressing its hopes.”

But the power of literature, for both writer and reader, according to Naji, is “something superior to moralizing and edifying.” He illustrates this poignantly through a story about one of his cellmates, nicknamed the Rhinoceros. One night Naji wakes up to find the “famously arrogant and unfeeling” Rhinoceros crying. When asked why he’s crying, the Rhinoceros responds, “It’s my feelings, man. They’re too much for me. I need to get them out.” When probed further about the source of these too-big feelings, the Rhinoceros confesses it’s down to a book, a book that Naji tells us is “a best-selling novel in a genre you might call Islamic romance.” In other words, hardly a work of “literature” as the academy or canon might define it. Still, something about the book moves the Rhinoceros so much he can’t help crying. At some point, Naji flips through the book, trying to see what secret it contained that might have reduced a man like the Rhinoceros to tears. But he finds that there is “no secret to the novel; the secret was somewhere else.” It lies in the fact that “words, books, and literature [have] an inner force, a hidden strength that might be stored inside a sentence or a word or a letter.”

Naji doesn’t say this, but it is in fact implied: that that strength only comes into being in the alchemy between writer and reader. Otherwise every book would move every reader. And so while the power (and function) of language is essentially one that exists in relation to a context — as the book makes abundantly clear with its examination of various dictions: of the prison, the courthouse, the street — the real power of literature realizes its full potential through a relationship. A relationship whereby the two selves in communion only come into contact on the page, through the words. And it is always a reciprocal one. After all, the writer necessarily creates with a reader in mind, no matter how abstract or unknown. The words are never not being set down without the awareness of the fact that they will come into contact with someone else on the other side of the page, or without the consideration of what those words might communicate to that someone (which, as experienced writers come to grudgingly acknowledge, often bears only tenuous relation to the writer’s own intended meaning).

This of course is the crux of the issue that lands Naji in prison in the first place: what he perceived as innocuous, especially when compared to other writings of a more political nature, was seen to be causing harm to “public morals.” And ironically, he finds that “the language [he] was imprisoned for using [is] standard fare inside the prison.”

While Naji was on the inside, on the outside he became a cause celebre. PEN America bestowed him with their PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award. They also sent a letter, signed by over a hundred writers, to Egypt’s president Sisi, “demanding Naji’s immediate release.” (Proving that PEN America is happy to mobilize its clout when it deems the cause uncontroversial and its support non-threatening to the status quo, but I digress). This, too, is ironic, because at every turn in the book, Naji rejects the idea of being a martyr for free speech, and places considered distance between himself and other writers, like Alaa Abd el-Fattah, sent to prison for the courage of their convictions.

Writing is such a famously abyssal undertaking — a relentless confrontation with the limits of one’s own intellect, patience and imagination — that no one would venture to do it if there weren’t an equally transcendent pleasure in it.

In fact, he tells us: “Before I went to prison, I wasn’t brave enough to think of myself as a writer.” Which is what makes prison such a bitter pill to swallow. He had been so aware of the “historical lineage [he] seemingly belongs to,” whereby writers are subject to various sorts of punishment for work that steps out of line; he had taken care to be “very cautious.” And in prison, he kicks himself for his miscalculation: “Why did you do this, Ahmed?” he asks himself. “Did you really have to write that stuff?” He’d just been “messing around, killing time.” And so “how had the game suddenly gone [so] far,” to the point where it had landed him in prison?

That definition of writing as “messing around” and “killing time” is intended as a dismissal of his younger, more naive relationship to writing. But a kernel of this idea remains visible in his more mature assessment of what the craft means to him.

He argues that for him, the “noble guises” in which writers “cloak” their desire to write — “intellectual edification, revolutionary commitment, self-expression, dialogue” — are just “pretexts… attempts by writers to distract from their central motive, which is their own satisfaction.”

It’s actually such a simple and obvious proposition: that the fundamental motivation behind most endeavors, and certainly artistic ones (which offer little financial motivation), is pleasure. Indeed, writing is such a famously abyssal undertaking — a relentless confrontation with the limits of one’s own intellect, patience and imagination — that no one would venture to do it if there weren’t an equally transcendent pleasure in it. And part of that pleasure is in fact in confronting those limits of the self, and then finding the places where they can be pushed, or where they are merely illusory, self-imposed rather than fixed. “I didn’t have anything to offer to society, “ writes Naji. “I just found that writing was a way of knowing and understanding myself.”

There might seem to be an inherent contradiction in the fact that Naji continuously rejects the role of art or literature as a tool of social change and yet elsewhere also maintains that words are “a terrific, untouchable power, capable of destroying society and its values… a magnificent toy.” But the answer in fact lies in the contradiction itself. For, as Naji maintains in a chapter appropriately enough entitled “Anti-Manifesto”: “writing is itself a way to understand [the full dimensions of the writing process], a way to doubt and question. Forced to defend myself,” he continues, “I always felt like the defense itself became a prison in which my relationship with literature was confined.” Under that definition, Rotten Evidence — doubts, questions, contradictions and all — can only be deemed a successful attempt at breaking out of that particular prison.