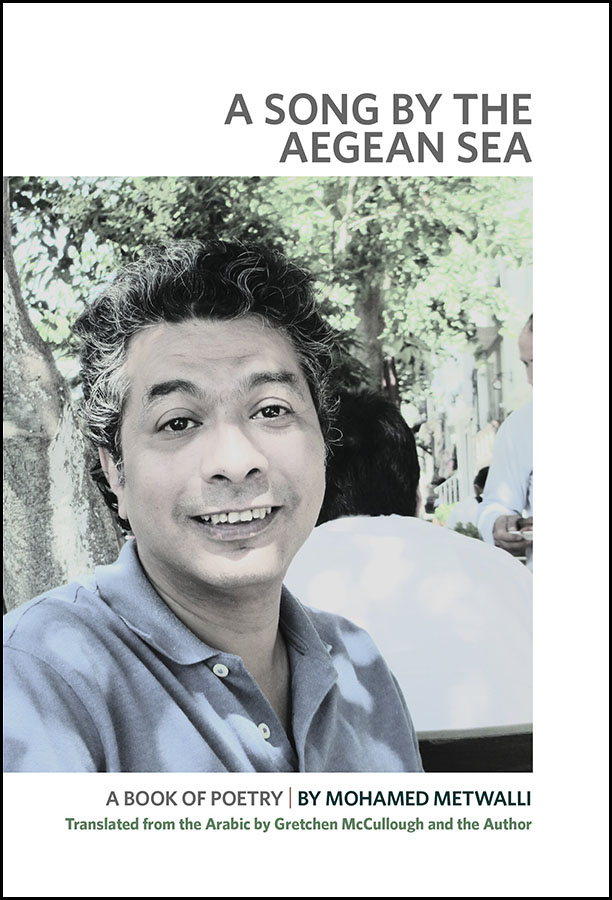

A Song by the Aegean Sea, poetry by Mohamed Metwalli

Translated by Gretchen McCullough and the author

Laertes Books (May 2022)

ISBN 9781942281269

Sherine Elbanhawy

In a world where it is increasingly difficult to travel, whether because of the pandemic, financial constraints, or the relentlessness of our routines and daily responsibilities, Mohamed Metwalli’s poetry collection A Song by the Aegean Sea becomes the perfect form of escapism.

Transporting and transplanting the reader to captivating Izmir, his words bring the cosmopolitan Turkish city to life, each vibrant scene teeming with nuance and detail: gypsies selling flowers alongside the protesters in the poem “One Flew East, One Flew West, One Flew Over the Izmir Bay”:

The gypsy seller of national flags

Wished to join the demonstration

or the roving musicians stopping to play soccer:

You belched roving musicians

Playing ball in their leisure time

Leaning their instruments

Against the wall of your exhausted lung

and the mussel sellers in a heated duet with the State:

As for the mussel sellers

Chased by the municipality

They blew safely out of your nostrils

With the smoke of tobacco.

We walk beside him through the streets of Izmir, listening to his conversations and observing through his eyes:

An orange moon

Above the Aegean Sea

Viewed by a couple of tourists coming from Egypt

From a hotel balcony

Who never believed—till this moment—What they had beheld!

This is Metwalli’s fourth collection, and it is beautifully captured by Gretchen McCullough’s careful and perceptive translation. In her introduction, she describes the poet traveller as a “singer of the Aegean song who yearns to become part of the scene. (…) It’s an impressionistic yet surreal canvas from a stranger’s point of view.”

I become enamored with the Izmiri landscape, and I am not alone; the picturesque coastal mountain bathed in sunlight moves the gypsy into song: “The gypsy rose-seller as well/Gazed at it/And burst, out of the blue, into a melancholy song.” As well, memories stir, “How reminiscent of Beirut is tonight! Pins of lights adorn the coastal mountain” and introspection prevails, in “Who Dares Approach”:

And remember the word of Gibran

Whence, an Egyptian poet stood

In front of his tomb—on the mountain top—in Beirut

Getting the goose bumps

Since the spirit of Gibran was infused into his veins

Telling him some of the old parables.

And, in the same poem, ghosts encroach:

Yet the words of Hipponax

Kept hovering above the place

Accompanied by his ghost

And ready to assault the veins of any poet

Who dares approach!

The poems are in chronological order, with one 2014 January winter sandwiched between two June summers (2013 and 2014). All the poems emanate from the poet’s stays at the Izmir Palace Hotel, where his viewpoint, interactions, and observations are almost voyeuristic, in “Occupied by the Sea”:

When he met her between the two palm trees

And kissed her beneath the hotel

When she glanced above

And the Bohemian poet, from his balcony, smiled to her

And she smiled back.

We meet the Greek Smyrna, today Izmir, through its living inhabitants, its unsung heroes, the restaurant waiters, street vendors, construction workers, gypsies, tourists, and even its birds (seagulls, ravens, larks, one dove, and one hoopoe), “To the carcass of a dove/Struck by lightning in front of my very eyes/Devoured, later, by the raven and the seagull.” The street cats and dogs are sometimes described as fat or stout and pepper the poems, interacting with the humans, the Aegean Sea, and the city at all hours of the day and night. The dog’s song, “The coastal dogs howled/Steering their heads towards the sky,” contrasts with the lazy lounging cats, “Who spend half of their time/Devouring the leftover fish from the restaurants/Or from the fishermen/And the other half, sleeping/Or licking their bodies.” There are even poems dedicated to each, “The Smile of a Dog” and “The Cats of Izmir.”

A palpable levity can be found in several of the poems, for instance, “A woman in her white wedding gown/Wails in front of the sea/After the groom jumps into the water for his life/Nothing of him later appeared but a black smoking suit/Afloat with an exclamation point on top!” and Metwalli’s tone is often playful: “A raven alighted on my table/Pecked at my pistachios and tasted my wine/Then gave me a quick reproachful look.”

Love is a theme, a thread that runs through Izmir. “Two lovers froze under a shrub,” and Metwalli captures many intimate moments, “Two lovers in a seaside restaurant/Clinked their glasses/To an illicit night,” as if simply being in the city enables these moments to occur, “And the lovers who sheltered/Under the shade of a shrub/Away from the sun and the curious eyes.”

The orange moon also recurs, “Who viewed an orange moon the day before—Gradually dimming into utter darkness till it disappeared—” with two poems dedicated to the moon in general, “A Raven, A Moon” and “A Smothered Moon”:

Oh my, oh my!

Where did my moon go

Behind the black clouds

Or did you not know?

Thus sang us the gypsy

For a pair of liras

That night, we,

Waxing lyrical,

Almost jumped into the sea,

A smothered moon

For which the farmers in my country

Kept beating the drums, banging the pots

Until it glowed

Is it so, you Aegean Sea,

That your moon suddenly vanishes,

Smothered,

Behind a black cloud?!

There’s a sensuality to the poems when Metwalli describes the body:

Then, the city was teeming within your body

You disgorged a few beauties

Sashaying along the coast

In skimpy shorts

and in the many moments of affection, embraces, and warmth:

In the night of Izmir

Giving him a deep kiss

Leaning back with her body.

The Aegean Sea is mentioned in practically every poem; it is the lifeline of the city and of the poet. Metwalli questions, “Is it in the Aegean Sea that souls get fathomed?”

As readers, we search for the answer in the sounds and literal places — the seafront, the park, cafés, restaurants — and figuratively, in “the bed of the sea” and “the dark sea.” The poet wants the reader to understand that all answers lie in the sea’s warped, out-of-sync, blurriness, that “the sea is enough.” “The page of the sea blends” with his words, and “the sea penetrates your pores/You sweat in beads of salt,” and he advises the reader to relinquish their body to the sea, “You still sit on your balcony/Between the two palm trees/In front of the water/And there comes the sea to absorb you/To draw the best out of you.”

It is an invitation into his surreal world, where life exists in a different dimension, a different color, beating to a different tune, “Don’t resist the sea when it occupies you—I know someone who tried to resist the occupation of the sea/Searching for an alleged independence, He ended up depressed and drowned—”

I feel swallowed whole by Metwalli’s words, and rebirthed in Izmir, surrounded by bustling tourists, larks, and lovers, in thrall to the city’s magical charm and its resounding sea, forever indebted to its orange moon.