Select Other Languages French.

Summer and its flames are behind us, we are told. A fragment of the truth, but welcome all the same. There’s a lighter mood in the land, too, apparently. Fingers to the wind, I feel — nothing more.

I don’t know!

Three simple words that come in such rich variety in Arabic — ma’barif, ‘ilmi ‘ilmak, ma ‘arfeh shi, ma fahmeeen shi… We’re saying them often nowadays in the Levant. In Palestine most of all. They’ve become our escape hatch in times that are bizarrely as quotidian as they are unusual. If they are not already repeating them in Israel, perhaps it’s because they’re newer to this existential quandary. They will soon enough, when Gaza is allowed to open its doors.

This expression is deceptive, though: I don’t know. The phrase seems to betray a temperament too languid for more than a moment’s reflection, but it actually connotes the psychology of turmoil. In the throes of chaos, you are not meant to know. You cannot know.

Some of us compensate with hectic chatter. But nowhere is the future invoked with anything more than a faint ray of light. The gleam of the eye, not of the heart; of insight, not of hope. Esperanza is in the embrace of sorrowful songs now, until the heavens unfurl a different season. We long for it, by turns anxious and eager. We have to, lest our optimism turn out to be another exercise in self-delusion.

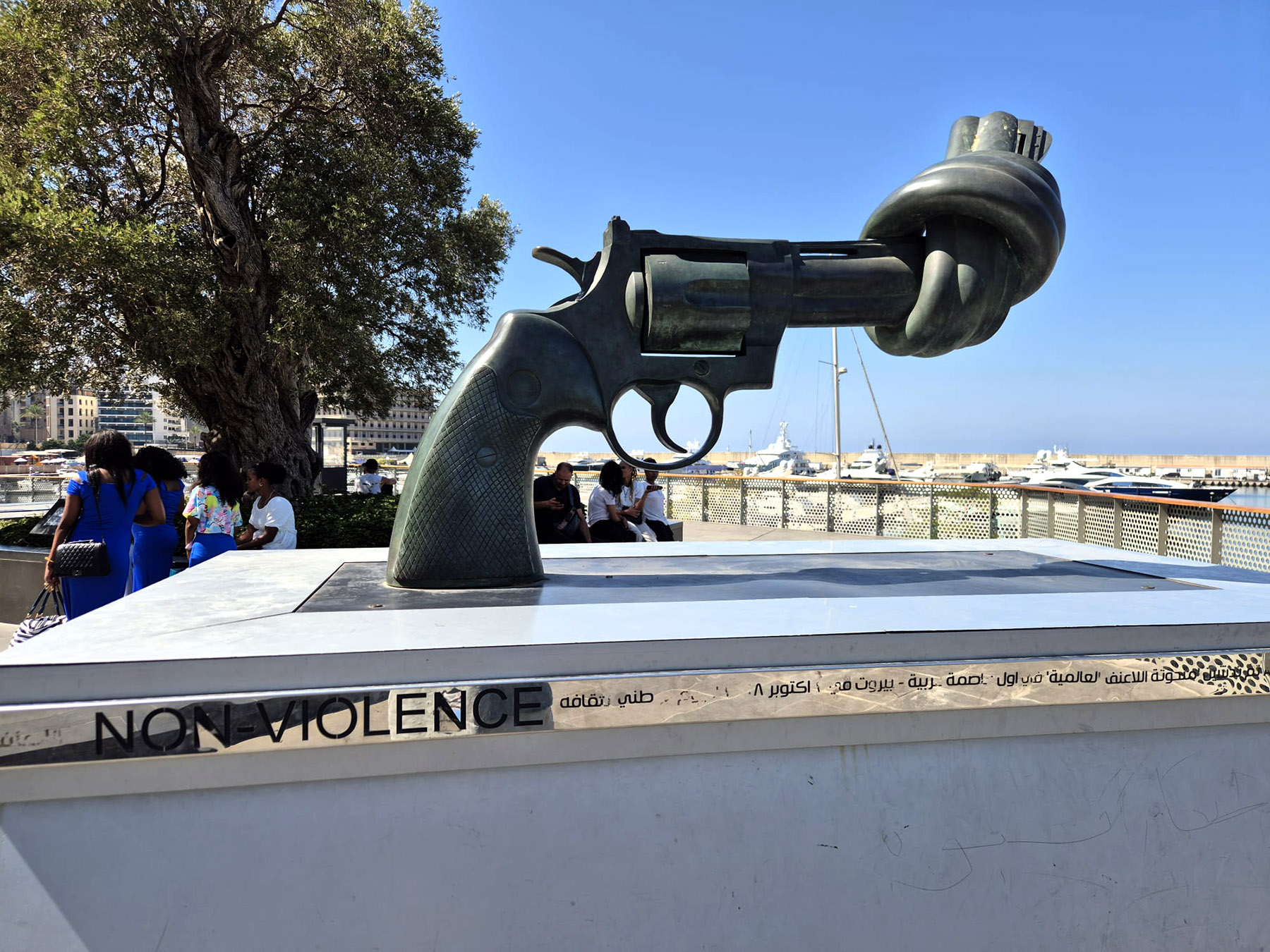

We tell ourselves to enjoy the respite — at least for a while, or until the next round. We do so, in Beirut, to the sound of Israeli drones above and the beat of the music below. We do so at the opening of magnificent exhibitions and elegant cocktail parties, in bustling cafés in the afternoon, over working lunches in quiet restaurants, at the gym in the morning.

The south struggles, we all know. It lurches, back broken, from one Israeli raid to another completely exposed; it suffers from the severe inequities besetting whole regions of our forsaken territories; from the indifference the state reserves for those it cannot or will not support. Many of us feel its pain, as we would a dear member of the family; others shrug as if it’s another country. Alas, this is an old Lebanese story.

But respite, please, for whatever it’s worth, we whisper — in shame or with glee. Such has been our solace in the Levant since we were wee children, even though the word’s promise has become so tattered, we can’t even weave from it an emotional hammock for an afternoon’s sleep.

Like good students, we begin to count our few blessings, matching each with its caveats: respite from genocide and famine in Gaza, but not from torment and heartbreak. Not from these. Not for an eternity. Respite, possibly, from formal Israeli annexation of the West Bank, but not from apartheid; not from accelerating erasure, settler gangs, and their enablers in the army.

Respite from sweeping Israeli assaults on Lebanese Nabatiyeh and Mays al-Jabal and Yarine, on Syrian Tartous and Aleppo and Da’raa, a small sample from countless aggrieved villages, towns, and cities. Not from the missiles and drones, their noise and violence; not from the scorched mothers, fathers, and toddlers in burned cars on sideroads and highways. Not from Israeli occupation either; pieces of us in Lebanon, larger pieces of them in Syria.

Never respite from this Israel!

Never respite from our other afflictions, either, those that feel like terminal illnesses. Not because there is no cure, but because, much like impoverished patients, we are denied the right to it. The maladies are not older than the beginning of time, as the lazy mantra about us goes, but they are older than the youth making our ancient region forever young. They are, these woes, each generation’s inheritance, for no decent reason that I can cite.

There’s no escaping the hard facts and the questions they impose. Is there? In the wake of the bloodshed and destruction wreaked on Gaza and Lebanon, on Syria, Iran and Yemen, such collapse of communities and states, such absence of leadership and ubiquity of tyranny; not only the tyranny of regimes, but the tyranny of conquest, cruelty, ineptitude, and poverty in all its forms, the worst of them the poverty of empathy.

Today, Hamas and Hezbollah are alone and lonely. Is there any sense at all in quibbling with that? In the presence of ceaseless Israeli predation, the people need to breathe and heal and rebuild. They need to do so as they find paths between their fragile habitats, the larger homeland, and even the larger world without which they simply cannot mend. How does the conversation about the very purpose of resistance after such enormous sacrifice not start with this hard fact? Not just for Hamas and Hezbollah, for all of us lonely Levantines.

Because today, our regimes are so very drained as well. There certainly is no sense at all in quibbling with that. Incapable of serious governance, they compensate with ersatz reforms, security, and control. How do our shattered societies recover in the void between such scandalous inadequacies and the challenges confounding us?

In this way, the particulars of our predicaments catch us naked in a downpour. In an expanse of tiny, untidy universes we have long been building — some out of conviction, many out of necessity through the ebb and flow of wars — we still live without a vision or a project for a collective self that is coherent and confident.

That has been and remains our circumstance. We recognize in it all the hazards and opportunities of a world that refuses to settle, and get to work dodging the first and foraging for solutions in the second. Is ours an act of resistance or a mode of acquiescence? Or both, in keeping with the paradoxes that animate us? I’ve been asking myself this question for a long time.

In earnest, I can’t make my peace with any one answer.

On Another Note

I am about to finish reading Robert Malley and Hussein Agha’s book Tomorrow is Yesterday. These two gentlemen were, of course, lead negotiators in the Oslo peace process, otherwise known as the treadmill. On the American side, Robert Malley was a dogged — if often rebuffed and frustrated — negotiator under two US Presidents: Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. On the Palestinian side, Hussein Agha had the misfortune (at least in my opinion) of being chief advisor to Yasser Arafat and his successor, Mahmoud Abbas.

The book is a well written, insightful, and candid chronicle of failure. It offers essential context to the catastrophe now unfolding in Israel-Palestine.

Ezra Klein and Peter Beinart each interviewed Malley and Agha for their respective podcasts. The conversations are an education; you’ll want to listen to both. Listen here and here.

Read this in Arabic in Al Quds.