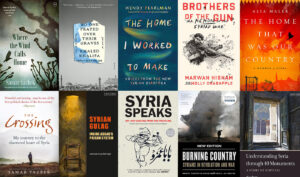

A TMR correspondent discovers the Ghassania, a renovated theatre helping to rebuild a devastated community (all photos courtesy Iason Athanasiadis).

HOMS: Tall, weatherbeaten, and wearing a beige headscarf and a black abaya with embroidered flowers, Ruba Bakir walks through the rubble-strewn streets of her old neighborhood. It was punitively destroyed by the Assad regime for being the upstart district of Baba Amru, an area that became synonymous with the Syrian revolution when rebels seized it in late 2011.

Bakir’s gait is careful, measured, laden with a caution inculcated by fourteen years of civil war.

“There was shooting, corpses lying in the streets, and panicked people running,” recalls Bakir of the day in 2012 when she finally fled Baba Amru. Aside from the ongoing, random shelling, arsonists had just torched her two elderly neighbours alive in their homes.

“It was like how I’d imagine Judgment Day will be,” she said. When she reached a shelter, a few hundred meters away from her old home, she recalled closing the curtains and turning up the music to suppress the sight and sound of her district being bombarded.

For Safaa al-Fakhouri, it took a sniper shooting her daughter dead to abandon Jurat al-Shayyah, another district of Homs that became notorious for the level of destruction inflicted on it.

After years of displacement, and having to raise tens of thousands of dollars in ransoms for her husband and father-in-law detained by the regime, she returned with her family to a sea of rubble. But just when they had cleared their yard, the eight-magnitude earthquake that demolished Antioch in 2022 brought down their neighbors’ house. They cleared it all over again and Safaa established a plant nursery that now supplies the residents trickling back to the shattered district with hundreds of potted plants “in a bid to reintroduce some green to the cement.”

The phoenix theatre

On a recent morning, both Bakir and Fakhouri leave their destroyed districts and head to a late nineteenth-century black basalt building in the Old City of Homs called the Ghassania. Formerly a theatre, it has just been renovated and is hosting a two-week workshop focused on women and heritage.

The theatre belongs to a Christian educational complex of the same name, built around the 1870s cotton boom that made Homs known as the Manchester of the East. In the mid-twentieth century, the Ghassania staged Arab nationalist-leaning entertainments in a period when Levantine Christians such as Michel Aflaq and George Antonius were founding the secularizing nationalist movement from which the Baath Party would emerge. In the 1970s, the building hosted the printing press of the city’s main newspaper. Already deserted, its life came to an end in 2012 when a bomb hit the building, during the siege of Homs.

Until now. The theatre’s recent renovation has blinked a light on in a repopulating district whose widespread destruction between 2012 and 2014 was all the more regrettable for wrecking a historical community that was a model of Christian-Muslim coexistence.

“I’d always pass through Old Homs and was sort of aware of its architectural features,” said Selwa al-Akra, a civil engineer, “but since doing this workshop I’m now always looking out for all the architectural details we’ve been taught or striking up conversations with the brass and copper-workers in the marketplace.”

Trust-building among communities is essential after a civil war that resurfaced latent sectarian tensions, sharpened by a minority-based regime that abused its message of protecting minorities to demonize an opposition dominated by radical Sunni groups — and, by extension, the dominant Sunni Muslim community. In the aftermath of the regime’s collapse, victorious Sunni militias have targeted Druze and Alawite communities in two rounds of extended fighting, although more extended score-settling has been averted.

“We could hardly recognize the district, or even our house when we visited it on the first day it reopened in 2014,” said Maya Shabu’a, who was a regular at the theatre as a child with her columnist mother. “We were shocked by the mass destruction and looting at first; later we unfortunately became immunized to it.”

Repeated crop droughts in the 2000s fuelled farmers’ discontent towards an urban-centered regime that ignored rural Syria, and fed an armed uprising that was extensively peopled by fighters from the countryside. Peter Schwartzstein, a climate journalist and author of The Heat and the Fury: On the Frontlines of Climate Violence (Island Press, 2024), believes there is a correlation between climate change and social upheaval, and that places like the restored Ghassania can act as a forum for overcoming communal hate.

“The thing about climate change is it’s contributing to a profound sense of psychological dislocation or even trauma for many people,” Schwartzstein told me. “The very fact that the surrounding landscape no longer looks, feels or smells like it previously did is pushing people to search for emblems of familiarity, and ancient sites are among the few holdouts, the few things that do look like they did in the childhoods of Syrians.”

A slow recovery masks chasms of distrust

It’s been a year since a coalition of western-backed militias managed to depose the Assad regime. Around three of the estimated thirteen million refugees have taken up residence again, and some of the shattered districts around Syria hum with new construction activity. Other areas, where the damage was too great and too many residents killed, remain eerily still — flattened concrete wastelands entombing thousands of unexcavated corpses, devoid even of birdsong.

Bakir was driven back years ago by the financial exhaustion of paying high rents. Wandering around her neighborhood, she is impressed by the rapidity with which new buildings go up. “This was not here last week,” she points to a dusty building overlooking a shell-damaged graveyard. Everywhere, new shops are springing up from the renovated ground floors of wrecked buildings.

Fourteen years of civil war cast a heavy shadow over the current fragile peace.

Bakir and Fakhouri are part of a generation of women who were compelled out of their households and into public life by the necessities of civil war and the regime’s targeting of males. While her husband avoided regime checkpoints by threading his way through secondary streets to his civil service office job, Bakir spent the war years running administrative chores for him and their two children, and foraging for the little food available. She registered to study law at the local university and joined a women’s group working in Homs and surrounding villages to support abused women. But the aftermath of the 2024 regime change finds her wearily admitting that the conservative, post-revolutionary normal is hard to adapt to, as she lights cigarette after cigarette.

“Now we’ve gone back to a new reality: the woman is covered, must stay at home and cook, dress in a certain way, and not go out too much,” she said, climbing into one of the minibuses heading into the city center of Homs. “The past decade of opening [of women’s societal roles] is being rolled back but, after having circulated, we can no longer go back to being silent home-dwellers.”

From revolution to civil war

Homs’ energetic protests at the start of the uprising earned it the sobriquet of capital of the revolution. These gave way to equally committed fighting by armed rebels against the now-deposed regime of President Bashar al-Assad. After shooting protesters dead, the regime escalated by shelling and bombarding large parts of the city, in a repeat of its 1982 suppression of a Muslim Brotherhood-led uprising in nearby Hama.

Historically, Homs and Hama leveraged their geographies in the center of Syria to become military garrisons in wartime and centers of trade during peace. They nourished rich Jewish and Christian communities that endured from Rome into Byzantium, becoming a center of the Neoplatonist philosophical movement that intellectually influenced Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

“Homs was once a globally influential city,” explained Charles Hayek, a Lebanese historian. “Julia Domna, the wife of (Roman Emperor) Septimus Severus, was a princess of the dynasty controlling Homs and for a while her nephew Heliogabal introduced the cult of ilah al-jabal, the god of the mountain, to Rome.”

Fighters from the Arabian Peninsula professing the latest installment of mainstream monotheism captured ancient Emessa (Homs) in 635 AD, just three years after the Muslim prophet Muhammad died in Medina. Parts of the population converted to the new religion, whose name, Islam, means submission. But there was no communal rupture, and the bonds of coexistence between the three religious communities coalesced throughout the Middle Ages and into the Ottoman period. Philosopher Roger Scruton describes this organic and extended process in his introduction to Syrian architect Marwa al-Sabouni’s book The Battle for Home (Thames & Hudson, 2017) as realizing “the idea of a city in which prosperous and poor, old and young, Muslim and Christian, live peacefully side by side in streets that they share, beneath a skyline respectful of their religious aspirations.” Prewar Homs, Aleppo, and Damascus constituted an “ancient solution to human difference — the way in which diverse communities settle side by side and imprint their agreements on the earth.”

The rise of Aleppo and Damascus sidelined Homs, but it remained a major industrial center till the eve of the revolution. The intense fighting resulted in half its population fleeing the city, which became, alongside Raqqa and Aleppo, one of the most extensively destroyed and looted in Syria.

“The last fourteen years were definitely not easy,” said Azza al-Abdullah, a tall, black-spectacled activist with a shock of trimmed gray hair, who sent her three sons abroad after losing her home to save them from participating in the civil war. “But the difficulties we came up against let us discover that we had surprising reserves of inner strength.”

In August 2012, a Syrian helicopter hovering over Homs’ mixed Muslim and Christian Hamidiyah neighborhood dropped the Syrian conflict’s first documented barrel bomb. The fighting that followed inflicted significant damage to the black-stoned churches, palaces, and mosques layering the old city. The Ghassania did not escape: a shaky cell phone video from October 2012 shows two locals standing in the rubble-strewn street in front of the building, describing how a barrel bomb had just penetrated the theatre’s roof but failed to explode.

“I felt helpless as I witnessed my city and all its heritage getting destroyed before my eyes,” said Lama Abboud, a local architect and the founder of Turathuna, a cultural heritage organization dedicated to Homs’ preservation.

Rebuilding the Ghassaniya

Al-Abdullah had strong memories of the Ghassania from its newspaper printing press days. Standing in its ruins, the first time she and Abboud met to discuss collaborating, she doubted it could be rehabilitated. But Abboud, a human dynamo who whirls through sixteen-hour days split between Homs, Damascus mand Leiden, where she is completing a PhD in heritage management, secured funding through the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund to embark in 2022 on a three-year renovation. Local masons and craftsmen coaxed the theatre’s pulverized stone, wood, and cement tiles back to life, even as the neighborhood remained in ruins and largely devoid of life.

“We tried to involve carpenters, ironmongers, and stonemasons to encourage the perception of traditional crafts,” Abboud said. “We inspired them to open new workshops, and so the renovation became a role model for the hood; now they’re doing repairs more sensitively and without using cement.”

Some of the theatre’s distinctive, flower-patterned cement tiles were destroyed in the bombing. Abboud found a workshop in Damascus and made identical new ones perfectly matching the surviving originals. Solar panel arrays ensured that the building is entirely energy-neutral. Two reservoirs absorb Homs’ increasingly scarce rainfall.

“I used to pass in front of the theatre and had no idea what it was,” said Shaza Abboud, a 35-year-old local woman who was displaced during the war but is now back in Old Homs. She is employed at the theatre and runs an activity called Memory of Place, where locals present historical possessions that add to knowledge of the shared past. “When I entered it, I was astounded by all that it contained.”

The theatre’s first public event was an October exhibit by Mounir Shaarani, a septuagenarian calligrapher with a worldwide Arab reputation, who landed back in Syria after a peripatetic Mediterranean life spent between Beirut, Athens, Cairo, and Tunis. He decided to break fourteen years of public silence by hosting his first exhibition in Syria at the Ghassania.

“Even though I was in Syria during these long years of war, I resisted exhibiting because the previous regime instrumentalized culture to present an image of normality,” Shaarani said, speaking to TMR in his Damascus studio where he is holding an exhibit of works often featuring controversial messages delivered through traditional Islamic calligraphy. “I chose Turathuna to exhibit in because it’s an independent organization, and the current government isn’t interested in the visual arts.”

Healing Homs

Back in the Ghassania, microphone-wielding trainers give lectures on Homs’ cultural and architectural heritage to visiting schoolchildren or help the workshop participants to work collaboratively on developing their personal projects. While displaced to Damascus, retired teacher Elene Deeb struck up an acquaintance with an artist, whom she commissioned to paint depictions of now-defunct traditional professions which she intended to sell at a Christmas bazaar. Another participant, fashion designer Dawlat Khaleel, is preparing handmade clothes and bags for her project.

“I didn’t know how to start my project, let alone how to develop and sustain it,” Deeb said, “and the workshop helped me structure my ideas, together with teamwork and mutual support.”

More than just acquiring project management skills, the theatre provided a venue for workshop participants to bond through song, dance, and long conversations, creating a reality rarely available across the sectarian divide. The uniqueness of the experiment was underlined in late November, when Homs was ripped apart by intra-communal fighting between Bedouins and Alawites — fighting that prompted a curfew and raised fears that the government was unable or unwilling to defend non-Sunni Muslims. Minorities interviewed by TMR spoke with trepidation of Sunni investors purchasing Alawite properties with a view to driving them out of the city, and returnees of all sects no longer living in mixed communities but ethnically segregating.

One evening, an older crowd gathered at the theatre to listen to songs that evoked pre-war life in the Old City. Workshop participants clapped and sang alongside older residents, including an 86-year-old lady who had married in the theatre decades ago.

“After many years of thinking that the destruction is irreversible, tonight offered us a joyful glimpse that perhaps normality is achievable once more,” said Ghassan Delloul, a member of the community and former Boy Scout, who composed several short plays staged in the late ‘60s in the Ghassania.

Fourteen years of civil war cast a heavy shadow over the current fragile peace. Bakir worries about a new generation of teenagers who have no recollection of prewar Syria and a childhood shaped by dispossession, death and no education.

“During these years we perhaps realized that we don’t much know each other and sometimes don’t much love each other, and these sectarian roots are now emerging with many people presenting their sectarian identity above their national one,” said al-Abdullah, the activist. “This is painful and alienates people from each other.”

When the evening is done and the lights turned off, Lama wanders around the theatre she restored, recalling the effort it took to repair it and considering the hard work of healing Homs.

“Without respecting each other’s differences, we won’t manage to build the Syria we’re all dreaming of,” she said. “And if we don’t build Syria all together, then we’re likely to go off the cliff all together.”