Bosnian American artist Aida Šehović has devoted many of the past 15 years to commemorating the Srebrenica genocide of 1995, the 30th anniversary of which falls in July 2025. Srebrenica was proclaimed last year as an international day remembrance by the UN. Her art project Što Te Nema (Bosnian for Why Aren't You Here?) is meant to offer a means of healing and resistance. We recently interviewed the artist in Munich, where she presented Što Te Nema, discussing commemoration, empathy and art. The artist went on to present the installation in Graz, Austria and at The Hague (Museum of Art).

Q: Aida, the starting point of your art is a simple cup of Bosnian coffee served in a fildžan (small coffee cup). You started collecting these cups in 2006 and you have been showing Što Te Nema in towns all over the world, interacting with people since then. Is there a difference in the kind of response according to the place where you are?

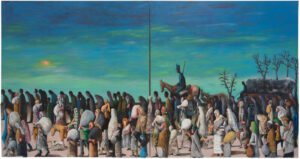

Aida Šehović: Yes and no; yes because each culture is different, of course. People have different norms of behavior as a society, especially in public space. In the US for example, which is more of an open culture, a lot of people tend to talk to each other on the street, even when they don’t know each other. When we were setting up the monument there that was the experience versus, for example, Stockholm, Sweden, where I remember speaking with people who were there for hours and didn’t approach, but they were there with us watching. And then only after two or three hours, some of them dared to come up, place the cups down and fill them with coffee as an example. Or they said that they felt they shouldn’t do that out of respect. They were just there. It was quite different from Istanbul, Turkey, where we performed in 2017 in Taksim Square. It’s probably the biggest city we have ever been in, and many people attended. Coffee and the fildžan are very familiar in Turkish culture. People were literally passing the cups from one hand to the other.

TMR: And on the other hand?

Aida Šehović: On the other hand, we have more in common because we are all people. And that’s the whole point. The hopeful thing for me is that through art, we are able actually to communicate. In the end, people become part of the monument. They enjoy and understand it, even if we don’t speak the same language. They’re curious, they ask questions and they do stop and care, which is nice. It’s important for me to keep doing this to see that there is a difference when I see people are moved. That’s the motivation with this kind of artwork. Obviously, money or gallery representation and fame is not the goal here. The objective is really to move somebody and see that people are touched through the work.

TMR: You shifted your work from kind of a nomadic memorial and from an event in the public space to an “archive of memory.” Why are you changing the concept?

Aida Šehović: If we call it a project, even though I hate that word, I started with Što Te Nema, but it has actually been evolving and moving throughout. Sometimes it’s more visible, sometimes less, but it’s always changing and growing. As an example, the first iteration of the monument, when it was installed in a public space with collected cups and coffee, was a performance where I placed the cups, but my friends were making the coffee, Bosnian coffee, on the site. I was the only one placing the cups down and pouring right then.

Eventually, it became more interactive when I was really in the background, which was the majority of the time during the 15 years that I traveled. I stayed in the background and others came to the public space — the passersby, participants, volunteers. They were the ones placing the cups and filling them with coffee.

Što Te Nema is also changing because of the size and the quantity of cups that have been collected, from 923 cups for the first iteration in 2006 to more than 8,372 cups in 2020. That year we surpassed that number which is also the official number of Srebrenica genocide victims, but not the final number. Many more people were killed, but 8,372 is the number that we use as a reference. And also in 2020, the cups had touched the ground for the first time in Srebrenica. They were in the place where the Srebrenica Memorial Center was built at the site of the atrocities.

TMR: Wasn’t it the ultimate action showing the cups in Srebrenica and having such a moving event there? How could you continue after that?

Aida Šehović: I felt that when the cups touched the ground on which men and women were separated and people saw each other for the last time, I thought there had to be a change. Conceptually. Because as cups were being placed, the majority of people who were with us in Srebrenica were families who directly lost their loved ones.

They have experienced the pain of the genocide personally, and they would actually name each cup as they were placing it down. After that the project became something else. And it also became logistically impossible to construct and deconstruct it in one day after we collected more than 8,273 cups. It became just too big as a temporary, ephemeral monument that travels. It outgrew its own form. Then this means it needs to become another form.

It was clear also that there is a need to find a more sustainable way for it to exist, which means that it needs to become some sort of a permanent monument, which is really hard for me to figure out. It should still have a participatory aspect, some kind of a ritual, but it’s very hard to imagine this aspect, if I’m not there.

TMR: There already is a monument site at Srebrenica for commemoration. So should Što Te Nema become something else?

Aida Šehović: I am rethinking the form and looking for something which might be permanent and part of it should be in Bosnia. But in the meantime, we are showing the archive which has recently been to Munich and Graz and which also has that participatory element.

TMR: We are living in difficult times right now. One of our problems is that there’s a lack of empathy for victims of conflict all over the world. You said you believe that art can contribute to connecting people. Is that still true? Can it contribute to people feeling their own emotion and to feeling empathy with others?

Aida Šehović: I have to admit that ever since the atrocities that we are witnessing in Gaza as an example, it’s been very hard for me to have faith in this kind of work, personally. Times change, right? The way we communicate changes. The way the Srebrenica genocide was documented and shared is quite different than the way we share and learn about atrocities today. On one hand it’s so much more open, and information obviously travels faster.

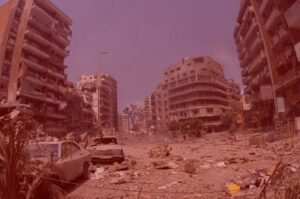

But there is also a really disturbing element. I don’t know what to call it exactly, but we are getting used to watching disturbing images of violence. And on top of that, we watch our politicians who are representing the people twist words and find excuses for inaction or for covering up their own personal goals and motivations and agendas. So, I don’t know what all of this becomes.

TMR: That’s discouraging.

Aida Šehović: And I honestly have been feeling very discouraged. But I have to say now, after Munich, where I observed so many people join and share their perspectives, their different points of view and backgrounds, that gave me hope. But when I’m alone, if you’re asking me, when I wake up and I open just Instagram and see all the pictures [of the genocide in Gaza] I don’t know what that does to us. I mean, I can’t even begin to imagine what it will do to thousands of people affected. Even with the occupation of Ukraine so many people have been killed, so many people have been affected. They have experienced trauma that I just don’t know…and we are all in it. We’re witnessing this. I can certainly speak on my behalf that I feel complicit as a human being.

TMR: How can we deal with memory under these circumstances? A country like Germany, for example, has a lot of monuments commemorating the Holocaust and at the same time it has a rise in racism, it has a far-right party in parliament and it is complicit with genocide in Gaza. So what use is memory if history is repeated?

Sehovic: That’s the question that I would say drives me constantly, because it is clear that the way we’re dealing with it is not enough or it’s not good enough.

TMR: Obviously.

Aida Šehović: Because otherwise we would stop doing what we’re doing. But at the same time all of it is important: we need legal processes, we need media. We need art in all of its forms.

TMR: With the cups you chose some objects as a symbol for atrocities, which usually stand for normal life. You don’t use photographs or other artefacts of the atrocities. Was the idea that it’s easier to connect for people with something rather positive?

Aida Šehović: It was certainly intentional that I chose the fildžan. It’s one of the reasons why I felt that art is the best form for myself to confront this topic and ask these questions because I’m honestly not sure that I believe in documentation. Of course, atrocities must be documented. But I don’t believe in this wide distribution of graphic images of violence, because I do think that they keep chipping away the humanity that we carry.

Watching a movie almost at any channel today, you can see somebody shooting 20 people just like that. How far we have come, what kind of comfort and dissociation do we feel, watching these violent images? It’s maybe also a sort of comfort that we are okay. We don’t even think about it anymore. I feel that does contribute to this lack of empathy. Because if you’re constantly exposed to this kind of visual imagery of violence, of course, you don’t feel anything anymore. The empathy disappears.