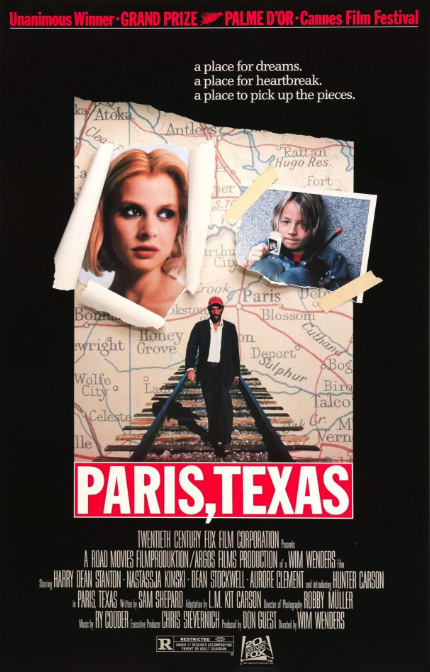

When a film becomes the blueprint for love, life, even death...

Michael first saw the film Paris, Texas when he was ten years old. His mother was on night shift at the hospital, and his father was playing dominos with the old Rasta guy next door. His sister, six years older than him, was out with her friends.

As he lay in front of the TV, Michael’s eyes were snared by a wide-open landscape of rocks and sand and hot orange sky. Everything in the film looked big. And everyone in it was sad. Their sadness felt familiar, though its causes were unclear. It left a delicious sting in his throat, like lemon sherbet. Transfixed, he watched right through to the end.

“I saw a really good film last night,” he said to his friend Chris at school.

“What, Back to the Future?”

“No, it was called Paris, Texas.”

“Paris is in France, you dipshit.”

The second time Michael saw Paris, Texas, he was 15. His father had run off to Birmingham with a woman twenty years younger. His mother worked and cried and tried to put her cares in the lap of Jesus. Worn down by it all, his sister had moved across the river to South London, and was expecting a baby with her fiancé.

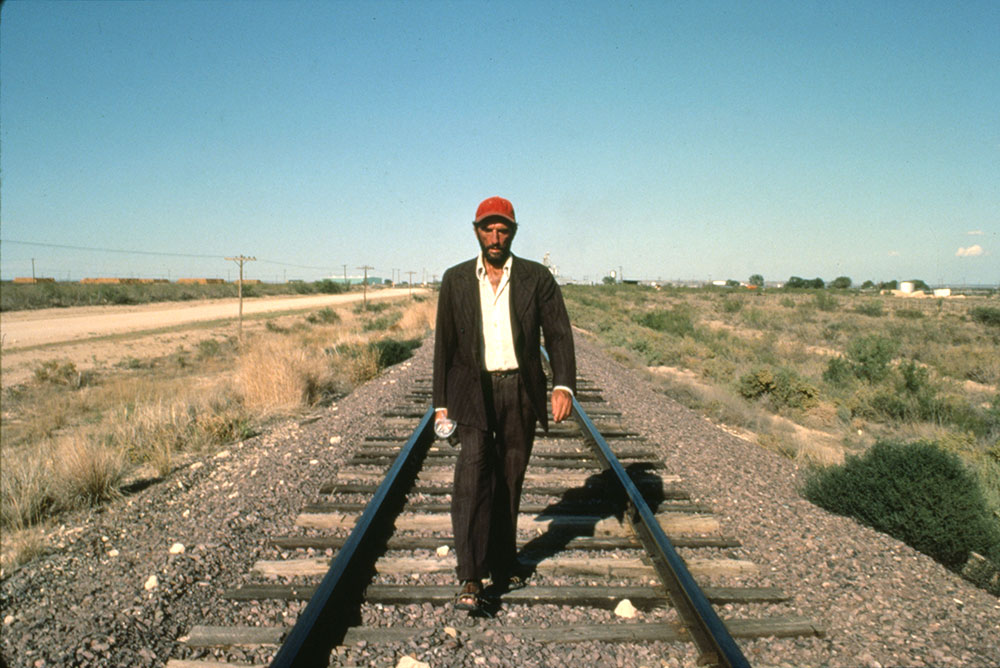

This time, the film made more sense. People were sad because of their own actions, and those of others. Chin resting on his hands, Michael savored the lonely journey of Travis, a grizzled man with unusually long ears. Crimson sunsets, a solitary guitar, those vast American highways. The film was so beautiful it made Michael cry. He wanted that heartbreak, too. Aged fifteen, he wanted to have loved and lost and loved again — in a Paris, Texas kind of way, not like his own parents. It didn’t take a genius to realize that film-sadness beat the real thing.

“I saw a good film last night,” he said to Nicole, a girl in his class whom he’d kissed once and fingered twice, though she refused to let him call her his “girlfriend.”

“Don’t tell me you watched Pretty Woman without me?”

“No, it was called Paris, Texas.”

“Paris, Texas,” she mimicked in a lisping, high-pitched voice before flouncing off with her friends.

Four years later at university, Michael watched Paris, Texas on video with his first proper girlfriend, Fiona. A student of Media Studies, she was an aficionado of the New German Cinema movement, which filled him with hope. But her running commentary about montage and framing and mise-en-scène left him cold. All art and no heart, it robbed the film of its magic.

Other viewings followed with subsequent girlfriends, each blighted by snoozing, nail-filing, or slack-jawed boredom.

Then he met Yara.

He wanted to have loved and lost and loved again — in a Paris, Texas kind of way … that film-sadness beat the real thing.

It was a Sunday morning in September. A back-to-school feeling hung in the air. Michael, aged 32, was heading south to his sister’s place in an empty carriage on the Victoria Line, balancing a box of mangoes on his lap, fragrant mementos of summer.

At Finsbury Park, a woman got on the train and sat opposite him. She was wearing an Adidas tracksuit, carrying a tatty gym bag. He looked up at her, smiled, and looked away. Seconds later, she did the same. As her gaze alighted on the mangoes, he felt an impulsive urge to offer her one. Should he? Or would she take it the wrong way? Wracked with indecision, he found himself fondling a mango in a way that might seem suggestive. His face turned hot. Without looking, he sensed hers had, too.

Lowering her head, the woman fumbled in her bag while Michael stared at the Tube map. When the doors opened at Highbury & Islington, she leaped off, fluttering a scrap of paper onto his lap. I’ve never done this before, it said. Here’s my number. Yara.

Afterwards, they agreed that while love at first sight was an infantile illusion, something special had happened that day.

“I felt like I already knew you,” said Michael, nuzzling Yara’s ear.

“Me too,” she replied, twisting a clump of his hair into tiny coils. “I felt like I’d known you all my life.”

Two months passed before he sprang the Paris, Texas test on her. There were other hurdles to clear first: friends to meet, parties to go to, art galleries to wander around with their arms encircling each other’s waists.

When people asked what’s your new girlfriend like? Michael would reply, with a grin that cracked the skin on his lips, “She’s the kind of woman everyone smiles at in the street for no reason.”

One crisp Sunday afternoon in November, after he and Yara had had sex three times on his sofa, Michael decided it was time. Sliding the DVD into the machine, he lingered over the picture of Nastassja Kinski on the cover. Was he imagining it, or did she look a bit like Yara? The heavy hair, the doe eyes, the full lips … different coloring, of course, but something about the features …

As the arid Texan landscape filled the screen, Michael stole surreptitious glances at Yara. Each emotion flitting over her face seemed to mirror his own. Finally, someone who got it — someone whose insides matched his. His heart filled with a tenderness he hadn’t known he was capable of as he watched Yara absorb the poetry of Travis’s ruined life: his wanderings in the wilderness, his abandoned son, his failed marriage to the luminous Jane — the revelation that Jane, desperate to escape Travis’s drunken jealousy, had set their trailer on fire while he slept, sending him running distraught into the empty night.

It was too perfect. A tendril of doubt crept into Michael’s mind. Was he indulging in wishful thinking? Projecting his own responses onto Yara?

When the film was over, she said, “That scene towards the end … So clever, how they filmed it.” Her voice came out husky. She cleared her throat.

“Which bit?”

“When Travis and Jane are talking through the screen, and he’s telling the story of how he’d driven her to set the trailer on fire. The way you can see their faces merging in the glass.”

“I never noticed that,” he said.

Squeezing her fingers with one hand, he swiped away the wetness on his face with the other. Not caring that he was sliding into corniness, he said, “This’ll always be our film.”

Now that Yara had passed — no, surpassed — the test, how could life be arranged so they were married?

As if reading his mind, she sprang a test of her own on him soon after this.

The look on her face when she asked him was pained, intense — not what the occasion seemed to merit.

“I’ve never introduced anyone to my parents before,” she said, rubbing her wrist bone in a circular motion, something she did when she was worried or upset. “But I want them to know about you.”

“Okay,” he said, trying to contain his delight. He could live with being the first ever guy to meet Yara’s parents.

“But we might have to pitch things a certain way,” she said.

“How do you mean?”

“Well, they don’t really get the concept of ‘going out’ with someone. They’re very … traditional.” He could practically hear the capital T. “My mum more than my dad,” she went on. “My dad’s cool — he didn’t make a fuss when I never went back to live with them after uni. But my mum … she’s, well …”

“Traditional?”

“Yeah. She thinks only prostitutes leave home before they get married. That’s what it’s like back ‘home.’” Then she said, all in a rush: “So I know this sounds weird, but we’ll have to pretend we’re engaged when you meet them. Oh, and we’ll need to say you’ll convert. We can always say later that we broke off the engagement. If we break up for real, I mean.”

“Yeah. We could pretend to do all that. Or, you know, we could actually …?”

Their foolish smiles seemed to dance off their faces, pirouette through the air and kiss each other.

“Why not?” she said. “Why the effing hell not!”

He bundled her into his arms, overwhelmed by the cuteness of how she said eff and fiddlesticks instead of fuck, and Schweppesy-Cola instead of shit.

Hours later, as they lay exhausted in bed, Yara said, “One thing about my mum.”

“What?” he replied, alert again.

“She’s got some stupid ideas about … people.”

“People?”

“Mmm. She thinks Irish people are always drunk, and English people smell of pig fat, and Greek people are sly, which is why they’re good with money, and Black people …”

The sentence trailed off. It didn’t matter. He’d got the gist. Yara’s wrist bone clicked as she massaged it.

“Never mind.” He kissed her forehead. “It’s a different generation. Anyway, I’ve got a plan to win her over.”

“What’s that?”

“When we walk in …”

“Yes?”

“When we walk in …”

“What?”

“I’ll flash my arse and say, ‘Kiss that, Mommy Dearest.’ That should break the ice, right?”

Like a lullaby, their laughter soothed them to sleep.

Yara set a time with her parents for the following Saturday. Michael met her at Southgate station, and they walked hand in hand past rows of pebbledashed houses. He’d been to the barber that morning and was wearing his gray work suit, minus a tie. Yara was in a long, sacklike dress that swamped her delicate frame.

“Oh, I forgot,” he said. “You never told me what to call your mum and dad.”

“You can call my dad ‘Doctor.’”

“Eh? I didn’t know he was a doctor?”

“He’s not. He’s an accountant.”

“So, what, he’s got a PhD or something?”

“No. His dream was to be a doctor, so people call him ‘Doctor.’ It’s a nice thing in our — their culture. Respectful.”

“Okay. What about your mum? Do I call her ‘Reverend?’ ‘Professor?’”

Yara hesitated. For the first time since he’d known her, she didn’t laugh at his silly joke. “I don’t know yet.” She frowned. “It’ll come in time.”

“Okay,” he said, mildly mystified.

They walked on in silence. “What’s wrong?” he said, when she dropped his hand and folded her arms.

“Nothing,” she replied brightly. There was a strained, hyper look in her eyes, like someone who’d been up all night drinking Red Bull and revising for an exam.

When they reached the house, she rang the bell instead of using the key pinched between her fingers. A short, portly man appeared, all hands and smiles and meandering vowels. Doctor.

“Come in, sir, come in, sir, it’s very nice to meet you, sir.”

In the recesses of the hallway, a lurking shadow revealed itself to be a woman. Tiny, sinewy, dressed in black. She looked like her bones would snap if you brushed against them. Never mind her real name; to Michael, she was “Gristlebones.” It floated as clearly into his head as if she had announced it herself.

“Hi,” he said, extending his hand.

Two kohl-rimmed eyes met his. They looked momentarily stunned, as if confronted by an apparition. Eventually, a small hand flopped against his. No word passed from her lips.

They made their way into the living room, which felt familiar, yet strange. Some features greeted Michael like old friends: a sofa covered in plastic wrapping, a mantelpiece crammed with photos and knick-knacks — china ornaments, old sweet tins, birthday cards going back five hundred years. Others introduced themselves for the first time: curvy, ornate furniture, like you’d find in a seventeenth-century French palace; a giant chandelier that grazed his head.

Left alone with Yara while her parents went to the kitchen, he groped for her hand, but she tucked both of hers under her thighs, giving him a distracted smile.

“What’s that?” he asked, nodding at the black velvet wall-hanging over the fireplace.

“The 99 names of God.”

“Oh.” Unbidden, the image of a Flake 99 ice cream popped into his head. As he tried to exorcise it, Yara said, “Now you want an ice cream, don’t you?” Their hushed giggles terminated when Doctor returned with a big silver tray.

Hours passed in a blur. A fluorescent pink cake gleamed and sweated on the coffee table. Mint tea was poured and drunk and poured and drunk. Beaming like a fairy godmother, Doctor dabbed his forehead with a handkerchief and bombarded Michael with questions.

“I work in IT,” said Michael. “At a big bank. Yes, it’s a permanent contract.”

“I was raised a Christian … But it’s all the same God, isn’t it?”

“No, my mum won’t disown me for converting. She understands.”

In the periodic pauses, Yara gabbled and fidgeted and dropped things. Michael’s heart ached at the sight of the red blotches climbing up her neck. Already, it was hard to tell where her discomfort ended and his began. She felt like a part of him.

From her narrow, straight-backed chair, Gristlebones looked on in silence. Tuning into her presence, Michael became aware of her sunless eyes darting from him to Yara and back again. He half-expected a forked tongue to protrude from her lips and put an end to the whole business with one swift, deadly flick.

“I’m very sorry, my wife has broken English,” said Doctor, placing his hand over his heart as if that was broken, too.

Finally, the ordeal was over. Yara ran upstairs to the toilet and Doctor went into the kitchen to pack up the cake: “Please, sir, please, you must take some to your mother with our best regards.”

As Michael hovered in the hall, Gristlebones materialized next to him. Jesus. Did she glide around on wheels? Giving her a quick smile, he busied himself checking his pockets.

She stepped closer to him. A gust of dark, musky perfume wafted into his nostrils. It reminded him unnervingly of Yara. Then, to his utter surprise, her face split open in a smile. Decades fell away in nanoseconds. Now he could see it — she was Yara’s mother, all right. The impish tilt of her eyes, the playful flick of her lashes. Her face might be full of cracks like a dilapidated house, but the foundations were the same. Regal cheekbones, a dainty nose. From nowhere, a wave of warmth swept over him.

They stood smiling at each other like long-lost family. Presently, her lips parted, producing the first sound he’d heard from her all afternoon.

“Pardon?” He leaned forward. Filled with affection, he nearly stroked her shoulder the way he did with his own mother. At first he thought she was speaking another language. Her own language? Was she trying to teach him something?

Sound crystallized into meaning. She was speaking English, saying two English words again and again. “Sister-fucker,” she was saying. “Sister-fucker.”

Mesmerized, he watched her spit the words at him not once, not twice, but three times.

“Are you ready?” Yara came galloping down the stairs. Before he knew it, they were out of the door, his arm sagging under the weight of the cake.

“Well!” Yara was flushed, giddy. “That wasn’t as bad as I expected.” She tucked her arm in his. “Sorry for getting uptight. I built it up into a massive deal. But they really liked you, I could tell.”

“Huh.”

“You okay, babe?”

“Yeah, yeah, all good.” After a pause, he said, “So your mum can’t speak English?”

“Not much. She can understand, but she says the words taste bitter in her mouth.”

“So she doesn’t know any … like, swear words or anything?”

She gave him a look of surprise. “I don’t know. Even if she does, it’s not like she goes round using them.” A question mark began to form in her eyes. He could tell she didn’t want it to. Her left hand inched towards the right, reaching for her wrist bone.

That’s when Michael decided. Never, ever would he be the one to make her fingers worry at her bones. Their relationship was poetry and beauty. It was spiritual communion, Paris, Texas — a happy version. Before her hand reached its destination, he lunged at the crook of her arm and tickled the fold he called her “baby crease,” letting the glorious melody of her laugh drown out everything else.

Six weeks later, they got married.

Time sped up for Michael once he was married. A normal lifespan no longer felt enough — he needed at least 300 years to spend with Yara. When he told her this, she laughed and said, “I’ve been thinking the same.”

This psychic stuff happened often. It wasn’t just a figure of speech when he said she was a part of him — he could feel her inside him, as if she inhabited his blood cells. If she stubbed her toe or cut her finger in front of him, he’d cry out in pain, and she did the same with him. People called them a pair of saps.

Oddly enough, this phenomenon didn’t extend to illness. As if their immune systems had struck a bargain, they never caught each other’s coughs or colds: One body took the hit for both of them. Proof of this came when Michael was walloped by a strain of flu making the headlines that autumn, while Yara remained untouched.

“I’m worried about you,” she said, stroking his head as he lay limp in bed. “It’s been more than a week.”

“I’ll be fine.” His voice was thin and echoey. His head seemed to have migrated to another solar system, soaring and floating among the stars, crashing into distant planets, throbbing like a red-hot sun. As for his body, it could barely make it to the bathroom and back.

“At least the temperature’s gone. Wish I could stay home with you till you’re better.”

“Don’t be silly. Go shake your moneymaker for The Man. We need to save up if …”

She smiled. Shortly before he fell ill, they’d decided to ditch the condoms on her 31st birthday, which was three weeks away. He didn’t need an official date, but Yara liked her milestones.

“You’re still as weak as a kitten,” she said.

“Wraoww,” he replied, which he knew would please her. Sure enough, her laughter scrubbed away her worry lines.

Yara went back to work the next day, leaving a key with their upstairs neighbor, Terry, a personal trainer who only ever seemed to train himself. At lunchtime, he popped in to heat some soup for Michael: “Don’t worry about germs, Mike, I haven’t had a sniffle since I started taking my new protein powder — I’m telling you, it’s turned me into Wolverine.”

When Yara got home, she brought him a plate of dark chocolate digestives — the only food he could stomach apart from soup — and told him about her day. As she got up to take the plate away, she said, “My mum’s worried about you, too.”

“Really?”

Yara’s face clouded over. “Yes, really. She’s not a monster, you know.”

“I never said she was.”

Yara twirled the plate around her hands. “I know she doesn’t talk to you much, but it’s the language barrier.”

“I know. Doesn’t matter.” Since his first encounter with Gristlebones, he’d been at pains to avoid being alone with her. Whenever they went round to Yara’s parents’ house, he glued himself to Doctor. Kind, courteous Doctor, who, confusingly, had started calling him “Doctor” too, upgrading him from “sir.” Two Doctors in the house, neither of them a doctor. Meanwhile, Gristlebones clung to Yara like a four-year-old reunited with their stolen puppy.

Yara sighed. “My mum’s funny sometimes. But, you know, she had a rough childhood.”

“How’s that?”

“She had ten brothers, and five died young. The wrong five, if you ask me. The others tormented her. One especially … He did some awful stuff to her, though she’ll never say what. She calls him shaytan—‘devil.’”

“That’s shit. I’m sorry.” He genuinely was. No one deserved that.

“It’s funny — she told me once you remind her of one of her brothers.”

“Which one?”

“She wouldn’t say.”

She seemed about to say something else, but stopped, her expression troubled. It niggled at him until she went on, after a pause, “Anyway, she’s worried about you. Although”—she giggled— “it might be because of the ‘swine’ in ‘swine flu.’ She’s so scared of the pig. Once I accidentally ate ham at a birthday party in kindergarten — I didn’t realize I wasn’t supposed to. She kept checking on me every night in bed for weeks afterwards, hugging and kissing me as if I’d swallowed bleach or something …”

Spurred into other reminiscences, Yara put the plate down and told him more stories from her childhood. He drifted off clutching her hand, comforted by the ups and downs of her light, eager voice.

Two days later, he was able to lie at a slight angle in bed. His illness was getting boring. The whole point of being off sick was to enjoy yourself — read, catch up on emails, watch films. He was craving the gorgeous melancholy of Paris, Texas, reconnection with that part of his soul. Two years had passed since he’d watched it with Yara. Life was busy now. Maybe he was ready to decamp to the sofa …

Five minutes later, he crawled back into bed, his head swimming.

Soon after midday, a key turned in the lock. Terry, doing his daily Florence Nightingale. Earlier than usual today.

“Yo, Tel-star,” Michael called out.

No reply. Light footsteps pattered through the hall as if a cat had wandered in.

“Terry?”

No sound. He held his breath. Just his luck. How would he defend himself against an intruder in this state?

The bedroom door creaked open. Michael’s muscles tensed. He braced to leap up.

A tiny bundle of black slipped in. The sight was so incongruous, he thought he was hallucinating at first. What was she doing here? She never came round on her own.

“Hi?” he said. It came out as a question.

She deposited a blue plastic bag at the end of the bed in a brisk, professional manner, like a district nurse doing her rounds. It made a sloshing sound as it came to rest. Then she walked over to his side of the bed, looking down at him.

“Hello,” he said. It struck him that now would be a good time to know what to call her.

She greeted him in her own language, using a phrase Yara had taught him. He responded in kind, proud of himself for remembering in his flu-addled state. But why was she here?

As if in answer, she reached into the carrier bag and pulled out a clear plastic bag full of dried herbs.

“Kitchen,” she said in English. “Make better.”

It was the most he’d heard out of her since she’d called him a “sister-fucker.” So Yara was right — his affliction had unearthed a kernel of concern for him. Maybe the sister-fucker episode was a terrible misunderstanding. On his part? On hers? On both?

She vanished from the bedroom. A few seconds later, he heard the kettle boil.

“Drink,” she said, returning with a steaming mug. The scalding liquid smelled vile, but it seemed to purify his throat as it slid down.

Reaching back into the carrier bag, Gristlebones pulled out a clay incense burner and a small lump of tinfoil. Incense and charcoal. He’d seen her do this at her house — go from room to room swinging the incense burner, muttering prayers under her breath. Sometimes she twirled the burner around Yara’s head while Yara hunched into a ball and closed her eyes. The ritual made him nervous.

“What if a hot coal falls on your head?” he’d asked Yara once.

“Don’t worry,” she’d said. “My mum’s got steady hands. I trust her.”

Once more, Gristlebones disappeared into the kitchen. He heard a hob sputter and die three times. When she returned with the smoking incense burner, she swept her arm out, saying, “Pig.”

She was going to cleanse the air of pig-flu. He gave her a thumbs-up, wondering belatedly if this was a rude gesture in her culture. Maybe there was something in these rituals. His own mother had a soft spot for traditional remedies, too.

As the sweet-smelling smoke filled the room, he watched Gristlebones’ deft hands and frowning face. Her rapt expression reminded him of Yara’s engrossed in some task.

It was strange, being so close to her. He wished he could talk to her. He wished he could ask her about herself. All the good brothers who’d died. All the bad ones who’d lived. What had happened to her, and which brother he reminded her of …

The incense must be doing something to his brain, fraying his thoughts around the edges. Through the smoke the old woman smiled, curves bleeding together.

What was her name, again?

Heavy-limbed, he floated in a place in which time unraveled. The old woman’s smile culled the years. It showed him who she was — a girl with dancing eyes and rounded cheeks. Her smile gave her the face of an angel. His angel, Yara.

Blurred hands rummaged in a mass of blue. Colors bounced like sunlight on a lake. Was he asleep or awake?

A shadow fell over him. The old woman crooning, holding something that sloshed like the sea. It splashed on the covers like the sea.

A smell — sharp and acrid — pierced his nostrils. Hurt his lungs. Make it go, make it go, make it go …

At the foot of the bed she tilted and rose. Steady hands, small, with a little yellow box. A rasp and a whoosh! Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God. Eyes lit, full of glee. A voice hissing, “Shaytan … shaytan.”

As the heat seared his feet, he tried to scream, but no sound came. Sleep had pinned him to a bed of burning flowers.

Space rushed and receded. He knew something like this had happened before, in a film, their film. The film that was a part of him, and of the woman he loved. Oh, Yara, oh Yara. Someone running, something burning. He flailed and clutched at the memory, but it kept slipping out of his reach. Paris, Texas. Paris, Texas …

*

When he woke up, Yara was by his side, pale and red-eyed, framed by a powder-blue curtain. Harsh lights made him blink. Hospital lights. She kissed his cheek and sat holding his hand. Minutes passed before she whispered, “What happened?”

His lips made a smacking sound as they parted. Brain scrambled, he lay staring at the white-panelled ceiling.

Crying, Yara reached for her right wrist. “Terry saved you. The sheets were drenched in white spirit. Two more seconds and the fire would’ve got you — he put it out just in time. He said my mum was there? She ran away? Don’t tell me she … deliberately?”

Unable to stand the look on her face, he glanced away. When he looked back, her eyes were fixed on his, pleading. Through her skinny turtleneck, her chest rose and fell in shallow breaths.

A nerve twitched in his forehead. Seconds stretched like elastic, and reality smashed into shards: Gristlebones had been helping him remove chewing gum from the quilt; he’d been cleaning a set of paintbrushes while in bed with the flu; a bottle of white spirit had grown wings and launched a kamikaze attack on him. As for why the match was struck …

Yara’s chest stopped moving. He felt the tightness in her ribs as if it were his own. But he was too tired and bruised to give her what she wanted.

“Yes,” he said. Together, they flinched.

“Okay.” She nodded hard. “We’ll talk later.” Mirthlessly, she laughed. “You must’ve been delirious. Terry said when you were lying in his car, you kept shouting, “Travis or Jane! Travis or Jane!”

“Oh. Yeah.”

“What was that about?”

“Our film. I couldn’t remember how it went. If it was Jane who set fire to the trailer while Travis was in it, or the other way round.”

“Which film? Who’s ‘Travis’ and ‘Jane?’”

They stared at each other.

“Paris, Texas,’ he heard himself say. “Our film.”

“Oh.” She thought for a moment. “I don’t remember too much about it. Was that the black and white one with Johnny Depp?”

He stayed silent.

Pulling at a loose string on her skirt, Yara said, “Random that it came into your head then.”

It was a while before he replied. “Maybe it was because someone tried to set someone else on fire.”

She winced again. He stayed still this time.

As he lay weak and cold, Yara talked about other things. She said his mother and sister were on their way, and she’d leave them to it and come back later. The hospital was keeping him for observation, she said, and he’d be released in the morning; they thought he’d drunk some herbal sleeping thing by mistake. She told him she had the rest of the week off work to look after him. She told him Doctor sent his love, and was distraught that he was in hospital.

Then she started crying again. She told him he was a part of her, and it hurt so much to see him lying there like that. “If only it was me,” she said. “Oh my God, I wish it was me.”

But Michael wasn’t really listening. Time had shifted shape again, and life felt long now. Long and strange and lonely. Overcome with fatigue, he closed his eyes. As he drifted off, he burrowed into something deep within himself. Something he now knew belonged to him and no one else.