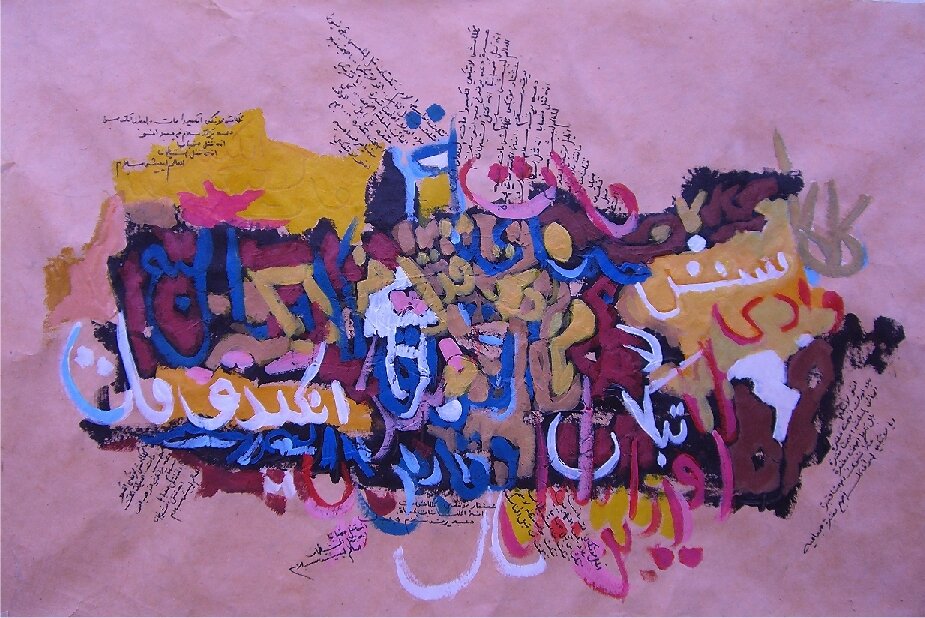

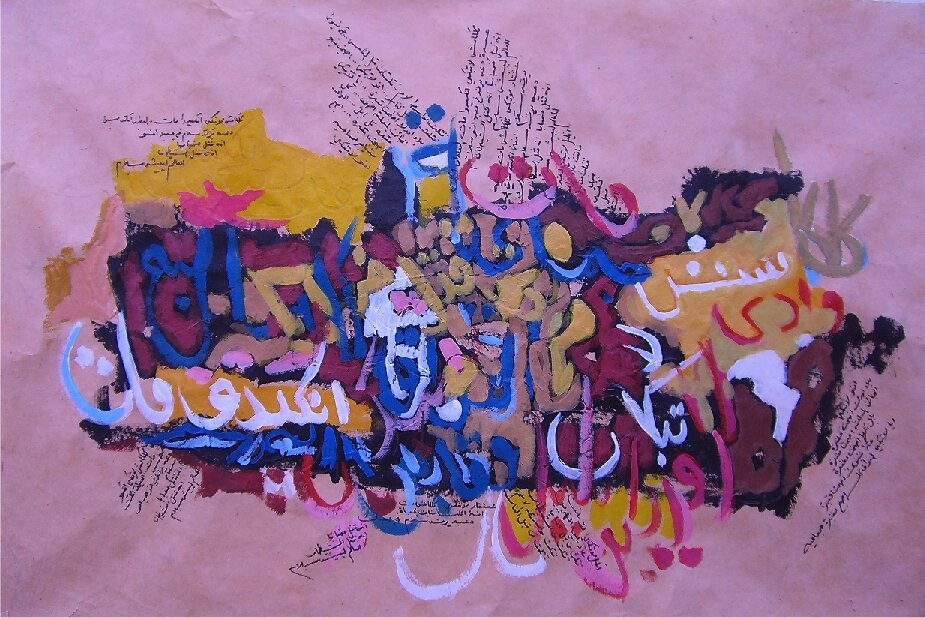

“Graveyard” by Baghdad native Paul Batou (courtesy of the artist).

<

<

Hadani Ditmars

It was in the surreal aftermath of the Anglo-American invasion of Iraq in 2003 that I first met Robert Fisk.

This was a time in Baghdad, much like post-Oslo accord Jerusalem, when we roamed through a brave new landscape, slightly dazed and giddy with possibility, willing to temporarily suspend disbelief and magically wish that old bogeymen would disappear, oblivious to the dangers that lay ahead. Deals with devils had been made, but somehow, illogically, we hoped that the better angels of our nature would prevail.

It was an upside-down wonderland world, but more Kafka than Carroll, where I was surprised to meet our former minders from the Ministry of Information, now employed as fixers and translators by hapless American journalists, who along with a plethora of returning exiles, US Marines and God knows who else, had infiltrated the now-porous borders of Saddam’s old police state.

It was an odd feeling to have English-speaking colleagues, after so many years of being the lone North American correspondent, settling for after deadline drinks with the likes of Miroslav from Serbian State Television. Suddenly fistfuls of dollars were being waved in faces and American accents filled the palatial hotel lobbies that had once housed Baathist officials.

In 2005, it would all blow up, quite literally.

The Al-Hamra Hotel, where Fisk had set up “office” in one of the standard ‘70s era suites along with myself and dozens of others foreign journalists, would be blown up by a car bomb — as would other hotels in Baghdad. A former honeymoon hotel with a shimmering pool, the Hamra was protected then by armed guards and meters of barbed wire

But for a brief moment, there was an odd sense of hope and even levity. Like tightrope walkers negotiating new terrains, we were caught up in the thrill of beckoning horizons. We didn’t dare look below the shiny surface, lest we succumb to paralyzing vertigo.

So it was somewhat of a relief to find myself at a Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) press conference one day, sitting across from the legendary Independent correspondent himself, his rumpled shirt and notebook in hand somehow reassuring of a certain normality in the midst of chaos and absurdity. We watched together as Colin Powell emerged and spoke from a faraway podium saying “We came here as liberators. We have experience being liberators.”

I was 35 years old and had been reporting from the MENA since 1992 and from Iraq since 1997, often for the Independent. I had returned to Iraq with a publishing contract in hand to write my first book, Dancing in the No-Fly Zone. Still I was slightly star struck to be sitting next to the Orwell Prize-winning journalist whose work in Lebanon and book Pity the Nation had so inspired me as a young writer working in battle-scarred Beirut.

But any lingering sense of awe soon gave way to on the ground practicalities. Fisk needed a photographer and soon enlisted me to join his traveling caravan of Shiah driver and Sunni translator for romantic tours of prisons and morgues.

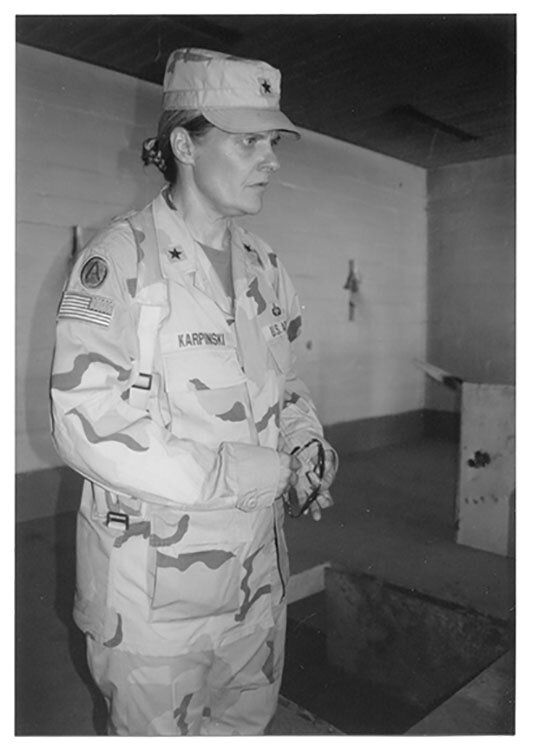

First up was an invitation to visit Abu Ghraib prison as part of a PR tour given by Janis Karpinski, some eight months before the scandal broke. I remember showing up poolside at the Hamra hotel that morning, dressed in respectable journo clothes — a linen jacket and skirt — only to have Fisk instruct me to disappear into a “local girl” hijabi, baggy-clothed identity. “We’ll be driving through ‘traditional’ areas,” he said, “You don’t want to stick out.” His translator wisely advised me to keep my more Western attire so as not to alarm the US Marines at the prison and I agreed. But in the end Fisk’s narrative won out.

Brigadier General Janis Karpinski guides journalists through Abu Ghraib, standing by the hanging platform in the old ‘death chamber’ (photo Hadani Ditmars, from her book Dancing in the No-Fly Zone). <

<

In a recent documentary about Fisk, called This is Not a Movie, he relates that, as a kid growing up in the suburbs of London, his destined career choice was influenced by Hitchcock’s film Foreign Correspondent, in which Joel McCrea’s character lived a glamourous existence. I had grown up inspired not by images from Hitchcock’s film, but by Fisk’s powerfully poetic pieces about war that both challenged the status quo and were imbued with a lyrical beauty. While Fisk was often self-deprecating about his meager Independent budget and modest digs, he was definitely a larger-than-life character. Working with him was cinematic, even if it turned out to be a weird movie.

As I would later write in the chapter of my book called “A Prison and Two Morgues” about our journey to the prison, “Besides their official duties, they (Fisk’s translator and driver) mainly played the role of ‘straight man’ and ‘rapt audience’ as Robert entertained us all with jokes, poetic recitals, impersonations and occasional show tunes. His manic joker personality was an interesting juxtaposition to his serious Middle Eastern correspondent persona. But then again, perhaps after years of covering some of the regions bloodiest conflicts his irreverent humor was simply a good psychological coping strategy.”

Oddly enough, in light of his later pro-Assad controversies, I remember Fisk telling the classic Syrian police state joke about the mukhabarat torturing a rabbit into confessing that he’s a donkey.

I arrived at the prison looking like the avenging sister of a prisoner and the Marines watched me like a hawk. Luckily Fisk charmed one of the young guards by letting him use his satellite phone to call his mum in Ohio. I watched — and filmed — as Fisk asked questions perfectly designed to trip up the Americans extolling the virtues of their kinder, gentler prison system. We even spoke to a creepy prison doctor with shifty eyes who told us that he had been there during the bad old days of Saddam. The climax of the tour was a trip to the old death chamber, where Karpinski ceremoniously lowered the hanging platform, where so many had died.

Three years later, Saddam Hussein would be executed in the same manner.

The following week was spent at the city morgues, speaking to grieving families whose loved ones had been caught up in the chaos of post-invasion lawlessness. A man getting ready to receive the bodies of his two sons, killed in a reawakened family feud, allowed me to photograph him. Two women whose brother had been shot by a lodger in an argument over a cigarette, began to cry as they told me their story, and I instinctively leaned toward them for an embrace. As one of the very few women correspondents around at the time, this was a unique honor.

That night, Fisk invited me for dinner at Nabil’s, a joint run by Ouday Hussein’s former tailor. It was a strange but necessary relief from visits to prisons and morgues. When Fisk, whom by this time I was calling “Bob,” sent the wine back, Nabil didn’t miss a beat, and had a waiter bring in a new bottle. Bob was a regular at the restaurant that would be blown up by a suicide bomber a few months later on New Year’s Eve. I remember chatting with him about PTSD in journalists, a relatively new topic at the time. He soundly denounced it as a crock, even as he recounted his experience of being beaten by a mob of Afghan refugees in 2001.

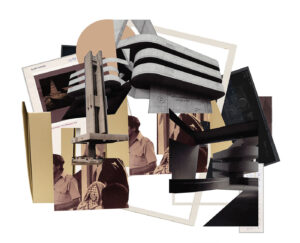

Hadani Ditmars’ photos appear in this Independent article by Robert Fisk, dated Sept. 21, 2003, making it difficult to refute the fact that they had worked together in Baghdad. <

<

After a week of working together, it was time to say farewell. Bob was off on another assignment, while I had to stay on for a few more weeks to finish my book research. But when I went to say goodbye, he seemed oddly absent, blank even. I asked him for the best email to reach him on so we could stay in touch and he replied, “Oh, I don’t really use email much.” So, I just gave him my card and walked away. I stayed in touch with his translator, now a journalist in his own right and still a friend, as I do with so many other colleagues I bonded with in Iraq. But I would learn that collegiality wasn’t one of Bob’s strong points.

Two years later, after my book Dancing in the No Fly Zone came out, I received a veiled threat from a close friend of Fisk’s while on stage at a joint panel. As the panel ended and as the audience applauded, she turned to me, smiling, and hissed, “Bob denies that he ever worked with you in Baghdad and he told me to tell you that if you continue to spread these lies, he will go out of his way to discredit you publicly.” In spite of my byline as his photographer in the Independent and video footage of us driving to Abu Ghraib together, I wondered — evidence be damned — what strange fiction Bob had conjured?

When my book came out, I was targeted by the likes of Michael Rubin and the neocons at the American Enterprise Institute who, for my efforts at documenting the suffering of Iraqis in the wake of a disastrous invasion, labelled me an evil “Saddamist” and, ironically, damned me for associating with Fisk. But I had forgotten that colleagues can be war zone reporters’ worst enemies. Before the invasion, there was a certain reporter with ties to the Canadian military who would routinely fax Arabic translations of fellow Canadians’ obligatory “Saddam is evil” stories to the Iraqi embassy in Ottawa, instantly blacklisting them. Plus ça change.

The following year, I was invited to read from my book at Ireland’s Immrama Travel Writing Festival, founded by Dervla Murphy, who once cycled across Rwanda. Other guests included politician Brid Rodgers — a key player in the Northern Ireland peace process — and well, Bob Fisk. Bob made himself conspicuously absent from the group panel, and when I attended his talk, mainly a tour de force presentation based on his 1,300-page opus The Great War for Civilization, he avoided eye contact. He refrained from attending my reading, which, along with chapters on Iraqi theatre and the national orchestra, included passages from that fateful PR tour of Abu Ghraib we had both attended.

There in the enchanting Irish town of Lismore, as the worst of the sectarian wars flared in Iraq, I flashed back to the Hamra Hotel in Baghdad. I remembered Bob scolding me one evening for chatting with an Armenian “security” man, whom he claimed was a CIA agent. But apart from that one incident, I was baffled by what might be motivating his behavior. The absurd exercise of trying to figure out what I’d done to earn the ire of the great Fisky, was oddly akin to trying to determine why I’d been blacklisted by the regime while reporting in Saddam-era Iraq. “You know what you did!” the Iraqi ambassador proclaimed before hanging up on me one cold afternoon in Ottawa when he refused to give me another visa. Now there was another mystery I’d never solve.

Bob came to speak once in Vancouver, several years later, to lecture on the rapidly disintegrating nation that had once been Iraq. During a Q & A, he refused to acknowledge my question, and scowled in my direction.

In 2015, he gave another talk at a Vancouver church, this time on ISIS, who were by now firmly entrenched in Mosul. Like the publication date of the Baghdad morgue article, the talk took place on September 21st, the UN’s International Day of Peace. By then, Fisk had been discredited by some as an Assad apologist and in 2018 he would infamously claim that there had been no chemical attack on Douma, Syria. Soon he would be mainly writing op-eds for the Independent, which had gone digital. He seemed changed somehow, perhaps less edgy.

The world had changed too. There was a new kind of cynicism in journalism now, perhaps brought on by a deluge of digital disinformation that made everyone suspect and everyone an expert. Bob’s door-stepping, Fleet Street-trained origins seemed almost quaint by comparison.

I stood with a group of admirers and students outside the church, while a local Jewish woman questioned him relentlessly about “the future of the peace process.” I waited quietly, hoping to have one last chance to make my own peace with Fisk — or perhaps with my memory of him as a former journalistic hero. I said hello and thanked him for his talk, and he smiled at me, back to his old charming self. Then I realized, he had no idea who I was.

“We worked together in Baghdad in 2003,” I said. “We did that tour of Abu Ghraib together and I took photos for your story on the morgues.”

“Ah yes,” he said, still smiling, still not really recognizing me. “Well, this is a beautiful city you live in,” he beamed. “Perhaps I’ll retire here.” And then he was off with the entourage of the white activist dudes who had invited him.

Tonight, as I wrote this, I dug out an old copy of that story on the Baghdad morgues we’d worked on together and pored over it. In the background, the blue light of my old television flickered with images of Joe Biden, who had once so enthusiastically championed the invasion of Iraq, and Donald Trump, recently endorsed by the Taliban. The next news item was about ongoing protests in Baghdad and the resurgence of ISIS.

Perhaps, I thought, I had really come to Bob’s talk that night in 2015 to make peace with memory itself. To honor the way that nostalgia and trauma can cloud judgement and make truth into a slippery thing; the way that old newspaper eras die lonely digital deaths and the foreign correspondent gets fetishized in online archives, old notebooks and yellowed copies of ancient articles. The way that war and conflict get temporarily erased by delusional, shimmering moments of hope, before someone sends the wine back, and it starts up all over again.

Rest in Peace dear Bob. We’ll always have Abu Ghraib.

<