While there is a growing interest today in indigenous archaeologies in Africa and the Americas — as well as the reconstruction of archives and practices that can inform us how indigenous people experienced the material past — the Middle East, as the outermost border of European modernity, remains a site of imperial contestation, where the foundational narratives of the West are amplified by association, and therefore, also by domination.

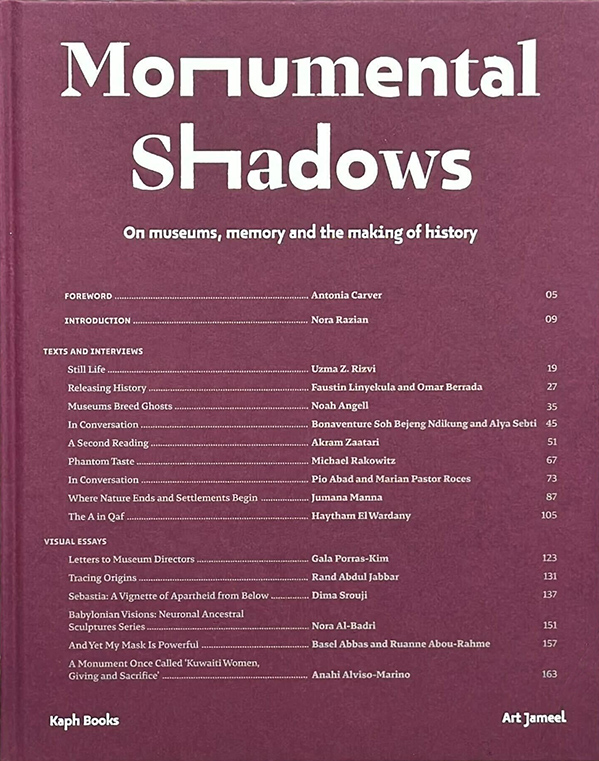

Monumental Shadows: On Museums, Memory, and the Making of History, edited by Nora Razian

Kaph Books & Art Jameel 2023

ISBN 9786148035456

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

When we speak about the destruction of cultural heritage in the Middle East, already from the outset, we are grappling with a number of crucial misunderstandings inherited from the framework of Western colonialism, both in terms of this vague geographical location and the content of this heritage. Alongside war and turmoil, heritage is one of the most commonplace subjects of news stories: the destruction wrought by the Islamic State at the Temple of Baal Shamin in Palmyra and the Babylonian site of Nimrud near Mosul; the demolition of a Phoenician-era former seaport in downtown Beirut; the interminable plunder of Palestinian antiquities; or the destruction of the old city of Antakya during the recent earthquakes. Cultural heritage is one of the most high profile victims of conflict in the region, and the subject of countless profiles, monographs, and surveys.

Less clear, however, is what we mean by this cultural heritage. Is it only the past of ancient civilizations? There are critics on both sides of the fence — those who decry the destruction of heritage as an assault on cultural memory, and those who regard the life of buildings as secondary to the human tragedy — but they share a misunderstanding about the nature of this heritage, as well as the complexity of relations between peoples and their built environment. Heritage isn’t something stable and fixed that can be easily isolated from everyday life. The concept itself is suspicious, not only because it is not identical to monuments or the past, but also given that the modern idea of heritage encompasses so many manifestations of human culture, including modern architecture, natural sites, archaeology, and living traditions.

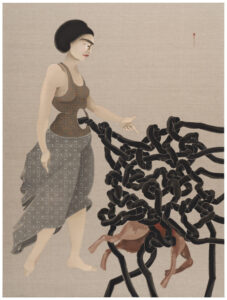

With the cruel realities of prolonged conflict comes collective amnesia and the disfiguration of cultural landscapes, so that artists find themselves in a position where they become unable to move seamlessly between past and future. In this situation, cultural heritage becomes a last frontier of history, a place where artists go to interrogate the relationship between the vast material heritage of the region, the authorship of historiography, and the political present. A recent book, Monumental Shadows: On Museums, Memory and the Making of History, edited by Nora Razian and published by Art Jameel and Kaph Books, brings together a polyphony of contemporary voices that have grappled with the difficulties of thinking about heritage.

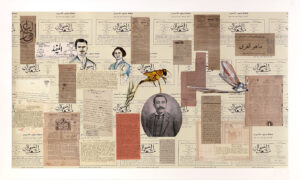

The book was born out of the 2019 exhibition Phantom Limb at Jameel Arts Center, a young institution that opened its doors in 2018 in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and was the Center’s first foray into broader questions of material heritage in the surrounding region. The exhibition included artists such as Ali Cherri, Akram Zaatari, Khader Attia, and Jumanah Manna, who have long been interested in understanding the present through traces of the past such as historical images, archival photographs, sites of archaeological destruction, and extracted artifacts.

In the following years, the overarching theme of the book continued to take shape, with influence from other exhibitions at Jameel Arts Center, such as that of Michael Rakowitz in 2020. Rakowitz is best known as a sculptor, using found materials and socially engaged practices involving dozens of other artists, artisans, and researchers, to reconstruct archaeological narratives and monuments. His works explore the overlap between the destruction of cultural heritage and the destruction of human lives, through the Babylonian heritage of Iraq (I chronicled his project about the traces of Armenian architects in Istanbul, The Flesh is Yours, the Bones Are Ours at the Istanbul Biennial in 2015, as well as the 2022 Istanbul iteration of his decades-long project of reconstituting Assyrian reliefs destroyed or looted, The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist).

As any immigrant knows, maintaining one’s cultural traditions in exile requires innovation and reinvention.

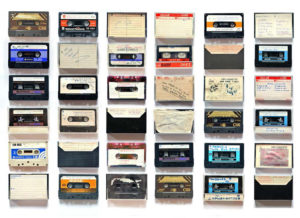

Rakowitz himself speaks in the first person from personal memories, and his narrative tells us how far and how close is the living heritage of Iraqis to the monuments of the distant past. The story revolves around an Iraqi sweet called mann al sama, made of chewy fragrant nougat stuffed with pistachios or walnuts, that Iraqis believe came down from heaven like the Biblical manna. Rakowitz first encountered it as the child of Iraqi immigrants in North America, but with the destruction of Iraq and ensuing sanctions, it became more and more scarce, and any available tin would be stored in the freezer for a special occasion. In recent years, as Assyrian groceries have opened in Chicago, Rakowitz has found a substitute mann al sama made with ghee, flour, and sugar, instead of the sticky sap from the leaves of the tamarisk tree.

He calls this substitute “a placeholder,” in the same way that his colorful “re-apparitions” of Assyrian reliefs from the Northwest Palace of Nimrud, made from colorful wrappings of Arabic foodstuffs available in the US, stand in place of the lost Iraqis as an act of hopeful remembrance. As any immigrant knows, maintaining one’s cultural traditions in exile requires innovation and reinvention, so that heritage in Rakowitz’s case is not just the uncanny flavor of nougat, but also the act of substitution: “I bought the tin, and into the freezer it went.” Rakowitz recounts that the tin of the substitute manna proudly illustrated a section of Ishtar Gate, taken by the Germans to Berlin in the early 20th century. It was in fact those colorful wrappings of food products in Arab markets in the US that first inspired him to reconstitute the lost and looted statues of Babylon, connecting the ancient past with the living present through the gesture of replacing a vanished presence with a contemporary artwork.

At some point, Europe decreed that other people had no history, that the history of the ‘other’ began with the arrival of Europeans.

Far from an exhibition monograph or an academic volume, Monumental Shadows brings together radically different voices, highlighting the plurality of meanings associated with heritage. Another chapter features Palestinian artist Jumana Manna, known for her research-intensive films and installations depicting the articulation of the colonial power of the occupation through agriculture, archaeology and law. In this chapter, Manna tells a story from Palestine, also about food: the 2005 Israeli ban on picking wild akkoub, a wild thistle whose cultivation and consumption botanists have traced back to Neolithic times. How much danger can a wild plant, growing on undisturbed rocky soils, pose to the occupation? Za’atar, one of the most widely used herb combinations in Levantine cuisine, was red-listed in the Israeli law books as early as 1977, when Ariel Sharon understood its symbolic value for Palestinians; after the siege of the Tel Al Za’atar refugee camp in northeastern Beirut by the Lebanese Christian Militia in 1976, Israel placed it under a total ban. (Rising to the level of satire, Israel has indeed banned the harvest of wild herbs including akoub, za’atar and sage that are essential in Palestinian cuisine. ED)

But the beating heart of the book’s engagement with the paradoxes of navigating contemporary heritage landscapes and its success in problematizing the function of the museum is, in my opinion, a conversation between Moroccan writer and curator Omar Berrada and Congolese choreographer and dancer Faustin Linyekula (the book includes perspectives from South Asia and Africa that at times feel marginal, but here finally coalesce) in which they discuss the interrupted histories of cultural artifacts stored in museums, and very often not exhibited for decades. Histories are not only interrupted, but held hostage in institutions, argues Linyekula: “At some point, Europe decreed that other people had no history, that the history of the ‘other’ began with the arrival of Europeans.”

The Congolese artist looks back at the Metropolitan Museum’s 2015 exhibition “Kongo: Power and Majesty,” which featured totemic power sculptures called Nkisi, and laments that the statues are not only scattered all over the world now, but also that those remaining in Congo are appreciated only in terms of their artistic value, because the archives of African museums have been written by colonial anthropology, ignorant of the role that these statues played in the life of communities: “Four years ago, when I went to Banataba, the village where my maternal grandfather was born, I was surprised to see that the sculptures there weren’t always thought to be precious objects. A sculpture was just a piece of wood in the corner of a room. A piece of wood impacted by the elements: humidity, tiny bugs… Dogs would rub against them.”

He goes on to recount the activation of their perceived powers: “And then comes the moment when a ceremony takes place. You bring out the piece of wood, you activate it, and then — it becomes magical. These objects aren’t magical all the time.” When Linyekula staged his choreography “Banataba” at the Met in 2017, he found in the museum’s storage a wooden statue with the label “Lengola people,” which is his mother’s tribe, and it is said that all the statues that went through a ceremony contain souls: “But this was the only statue from the Lengola people in the museum. What must it be like for it to be thousands of miles away from home, all alone?” The artist brought another statue from the Lengola in Congo so that it might keep the first one company for the duration of his performance, thinking that maybe they could communicate with each other.

The afterlives of artifacts of cultural significance are open-ended; they can still change, regenerate, and be reborn. They are not defined by the absolute otherness of the anthropological gaze or by the aesthetic of the ruin that regards the past as completely cut off from the present. Berrada responds that there is a colonial fetishism for authenticity: “Cultural phenomena must remain as they were found, because it’s assumed they were always like that, that they never changed or evolved. The way in which objects are placed behind glass, as well as how the description of works are written, confines them to rigid meaning.” The paradox is not that we fail to understand this material heritage, but that, as Linyekula remarks, peoples in the global south are racing to build new museums to convince Europeans we deserve to have the objects returned.

In my own work with prehistoric archaeology, my colleagues and I fully understand that the art object is an invention of modernity, and that the museological display behind glass was born out of the European cabinet of curiosities, and it does not respond in any way to the usage of artifacts in their original context. Yet we take this originality with a grain of salt; sometimes domestic, sometimes ritual, artifacts were often mass produced in workshops, and many survived only accidentally through being discarded or buried. But more often than not, they are now ownerless and their history cannot be fully reconstructed because many of the sites where they were found were subsequently destroyed by tomb raiders in order to satisfy the universal museum’s 200-year unquenchable thirst for yet more objects to display behind glass.

A personal anecdote: almost two years ago, while curating an exhibition for a Turkish artist, I came across a strange four-legged artifact at the artist’s studio that was simply said to be “African art” of unknown provenance. We used the artifact in the exhibition in order to highlight temporal ambiguity: Is this artifact ancient or contemporary? In fact, it turned out to be a Boli figure, created by the Bamana peoples of Mali, one or two centuries ago. The Boli is a sacred object used in altars by the Komo, modeled in organic materials such as clay, wood, bark, millet, and honey, and encrusted with sacrificial materials. Once they are sculpted, they have not reached a final form; they are constantly enlarged and reworked with the residues from sacrifices and rituals, and the work is perennially unfinished.

Ultimately, heritage is not necessarily about the past, but about what remains of the past in the present and the ways in which this present will transform the future of the past.

We know that both Picasso and Brancusi had Cycladic marbles of dubious provenance in their studios, but it also makes you wonder how easily plundered material can travel, especially in the absence of relevant scholarship (there are only a few Boli figures in international collections, including the Met), and the ways in which we are unprepared to deal with artifacts in terms of their own changing histories. While there is a growing interest today in indigenous archaeologies in Africa and the Americas — as well as the reconstruction of archives and practices that can inform us how indigenous people experienced the material past — the Middle East, as the outermost border of European modernity, remains a site of imperial contestation, where the foundational narratives of the West are amplified by association, and therefore, also by domination.

The relationship between cultural plunder and foreign interventions in the region is not simply a historical error of the past that can be easily fixed with the return of artifacts to new and sleek museums (it is estimated that some 15,000 antiquities were looted from Iraq in the chaotic aftermath of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003). Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, an Arab Jewish filmmaker and theorist, argues in Monumental Shadows that there is no restorative justice in repatriation of objects without addressing the cruelty of deportation. Azoulay speaks about the simultaneous realities of ongoing colonialism, in an aberrant contrast that exists between undocumented people subjected to maltreatment at the borders, and the objects taken from their places of origin that can easily travel, and that are “well documented” (but poorly provenanced), and treated with care by museums. The conclusion, drawn from her book Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (2019), is that it is not possible to decolonize the museum without decolonizing the world.

Archaeologist Dan Hicks, who has published a monumental book on the Benin Bronzes, and whom Berrada references for coining the phrase “unfinished events” with regard to the urgency of the bronzes’ restitution, writes in an earlier book with Sarah Mallet, about the similarity between the museum and the border, in the service of the state, as tools for controlling time and history: “Today, at both the museum and the border, time is a (post)colonial weapon.” In Hicks’ view, the museum and the refugee camp both play a role in deciding who can partake in modernity, its institutions, and technological imagination. It is also Hicks who has proposed a role for contemporary art in restorative justice: replacing looted objects with contemporary art. Rakowitz has made this proposal to different archaeological museums that exhibited his work, to no avail.

While the encyclopedic museum’s claim to neutrality is no longer convincing, the display regimes of archaeology and history — the main media of modern heritage — remain defiantly unchanged, and it is in the contemporary art museum where tools and strategies are being devised to cope with the challenge of formulating a whole new heritage environment where justice, conservation, and exhibition can coexist. And it is for this reason that what is really lacking in Monumental Shadows is a serious conversation about what the new universal museums of the UAE and other Gulf countries mean for heritage in the region, at a time when the universal format is being revised everywhere. Ultimately, heritage is not necessarily about the past, but about what remains of the past in the present and the ways in which this present will transform the future of the past.

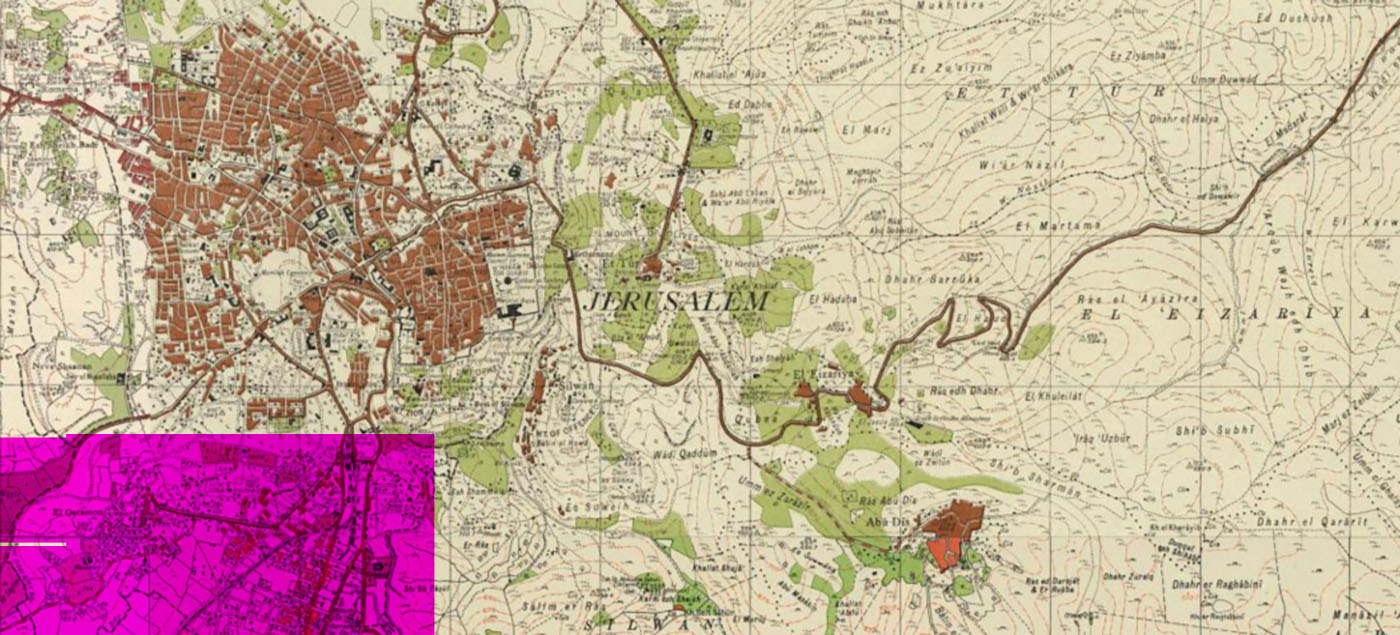

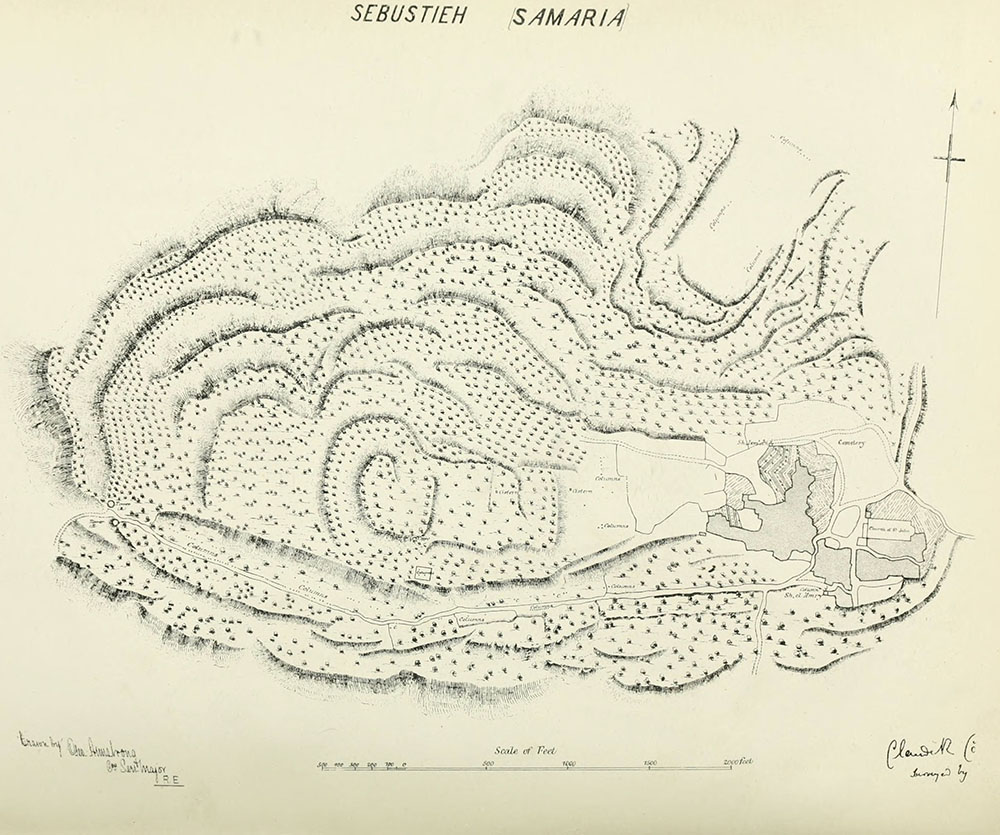

Arguably the most poignant aspect of Monumental Shadows assumes the form of visual essays reflecting on heritage by Palestinian artists Dima Srouji and the duo Basel Abbas and Ruane Abou-Rahme. Drawing on conversations with a resident of Sebastia, a small village northwest of Nablus in Palestine, Srouji, an architect by training, helps us visualize the stratigraphy of the archaeological site: “The city is alive and the monuments are used as public spaces for weddings, performances, festivals, walks and even a soccer field.”

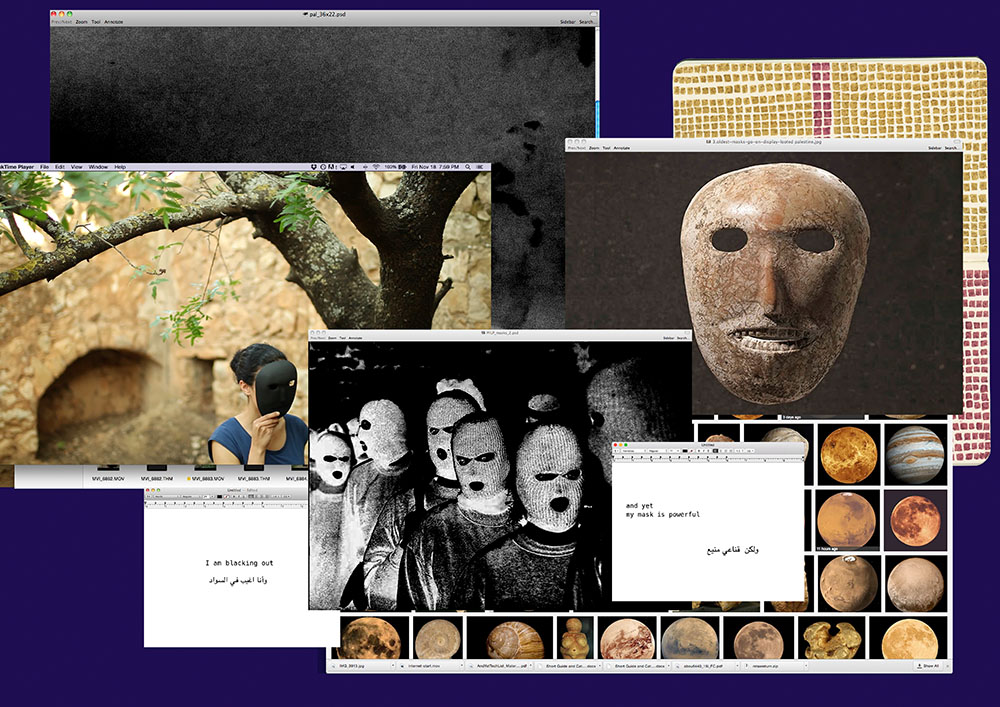

Sebastia is the seat of ancient Samaria, going back to the 9th century BCE. The site has been excavated since the 19th century; it contains the ruins of a royal palace as well as a Roman theater, separated by almost a millennium. But today the village is almost entirely encircled by Israeli Jewish settlements. Following the Second Intifada, the settlers have begun to take control of the archaeological site more aggressively, as though reenacting the exploitation of the local population for archaeological labor during the Harvard excavation in the early 20th century, as well as removing any valuable finds under military watch. Abbas and Abou-Rahme’s visual essay introduces their mesmerizing, ongoing video installation “And Yet My Mask Is Powerful,” which I was lucky to experience in person in Istanbul in 2017. The installation resurrects Neolithic masks unearthed in Palestine and is overlaid with modern poetry, inspired by a verse from Adrienne Rich’s poem “Diving into the Wreck,” describing a scuba-dive to a site or wreckage.

Often excavated in dubious circumstances (Michael Steinhardt, who has the largest collection of Neolithic masks from the West Bank, recently returned looted artifacts to Italy and Turkey), they are always referred to by Israeli museums as found in the “Judean Hills” or the “desert,” and are inaccessible to Palestinians. Based on an online tour of a major exhibition of the masks at the Israel Museum, Abbas and Abou-Rahme reproduced the masks using 3D modeling software. In their words, “the masks adorn the faces of those wandering in villages that were emptied and destroyed in the 1948 Nakba.”

Razian, the editor of Monumental Shadows and a curator at Jameel Arts Center, writes in the introduction that “heritage and inheritance share the same etymology and meaning — to be bequeathed something of value from others.” The fact that Monumental Shadows bears generous gifts of multiple heritages serves to complement this idea, but we also need to remember the words of François Hartog, namely that “heritage is a notion fashioned by and for crises of time, in which the issue of the present or the dimension of the present had always played a pivotal role.” Modern heritage as inheritance was born with the writings of Chateaubriand in the aftermath of the French Revolution, as a means to preserve its conservative legacy, and ever since has been tied to tectonic shifts in historical consciousness. Therefore, our heritage is not set in stone; it can suddenly change, and rapidly transform the past. As the anonymous sculptor of the Boli figure in Mali reminds us: the work is perennially unfinished.