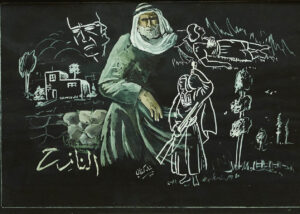

Palestinians in my experience, have been forced into an obsession with Israel, particularly for those living under occupation as Israeli law and military control every aspect of their lives. Meanwhile, Israel has educated its people to not see Palestinians at all.

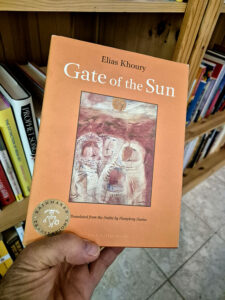

Three Worlds: Memoirs of an Arab-Jew, a memoir by Avi Shlaim

One World 2023

ISBN 9780861548101

Selma Dabbagh

In writing his most personal book to date, British-Israeli revisionist historian Avi Shlaim has taken the most political of positions. Shlaim, an Emeritus Fellow at St. Antony’s College, Oxford, has written various works of Middle Eastern history, including The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World and Israel and Palestine: Reappraisals, Revisions, Refutations. Three Worlds is the memoir of one member of an ancient civilization, the Iraqi Jews, whose community was ripped apart in the years following World War II. The author has since lived as a member of a minority, both in Israel and then in England.

The world of Shlaim’s childhood in Baghdad was rich both materially and culturally. “Iraq’s Jews did not live in ghettos, nor did they experience the violent repression, persecution and genocide that marred European history,” he writes, referencing the Christian hysteria against Jews that resulted in the Inquisition, the Pogroms and finally, the Holocaust. Iraq’s Jews were subjected to expulsion, he asserts, but not for the reasons claimed by the standard historical narratives. “My family did not move from Iraq to Israel because of a clash of cultures or religious intolerance,” Shlaim observes. “Our universe did not collapse because we could not get on with our Muslim neighbours. The driver for our displacement was political, not religious or cultural.” This political driver, he shows, was both external, underhand and deliberately divisive. This was a planned population transfer, which was not desired by, nor of benefit to, the population itself. Arab Jews, he argues cogently in Three Worlds, were the victims of a conflict that was neither of their design or in response to their collective desires, but that led to the annihilation of their distinct ancient culture.

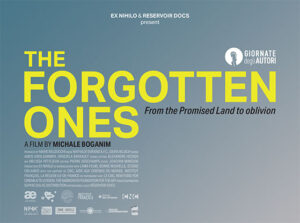

Few of those who are steeped in Palestinian/Israeli scholarship are unfamiliar with Avi Shlaim the historian. As an intellectual figure, he is at the top of his game; not only highly acclaimed as an academic, he has also submitted expert evidence to the International Court of Justice, the world’s highest court, to assist in its adjudications on Palestine/Israel. He has made a difference politically, not as a result of his scholarship alone, but in addition to his fluency as a writer and energies as a speaker, which has led to the outreach of his ideas and his words. His voice is vital as an Israeli Jew in guiding us towards a peaceable future. He believes in a one state solution, with equal rights for all from the river to the sea, as do I. He has been threatened and has stood firm. One can only wish there were more Israeli Jews who shared his beliefs, outlook, intellectual rigor, passions and courage. He has always been in the minority, both as a Jew in Iraq and then as an Arab Jew in Israel, and finally as an anti-Zionist Israeli Arab Jew in Britain.

Three Worlds is the story of the man behind the intellectual. It is a surprising, entertaining and honest account of the first eighteen years of his life. Shlaim, as a narrator, comes across as quirky, curious and loveable. Here is one of his earliest memories:

I was two or three years old, in the care of my nanny, sitting on a Persian rug on the roof of our house, surrounded by toys of various kinds, including a grotesquely large pair of plastic scissors. I chose to try out the scissors on my nanny’s big toe. She seemed to enjoy the game hugely, roaring with laughter, and encouraged me to press harder and harder on the scissors. The harder I pressed, the louder were her giggles.

“This episode,” he writes “is a miniature of my family life in Baghdad: we led a relaxed and comfortable lifestyle, surrounded by nannies and servants; I was privileged and pampered, and even seemingly naughty behaviour on my part was met with affectionate indulgence; the end result was a happy and care-free childhood.”

There is a confidence and freedom of spirit in his character, that is, to my mind, connected to his capacity for bravery. Historians possess the wide angled view of the past that enables them to grasp the potential for change in the future, by acting in the present. State boundaries are not fixed, methods of governance are susceptible to challenge, individual actions and relationships do count. Apartheid can be dismantled.

In Three Worlds Shlaim shows how Iraq was deliberately made unsafe for Jews after the creation of the State of Israel in 1948. The family left when he was five years old. His early years in Israel were not easy. He clammed up and was academically weak. “In my last two years in primary school,” he writes, “I was increasingly afflicted by what today might be described as existential angst. What I experienced on a small scale was what Iraqi Jews experienced all over Israel: disrespect for our Iraqi provenance; ignorance of our history; disdain for our culture, denigration of our language; and social engineering to make us fit into the new European-Zionist-Israeli mould.” It is not surprising that it was tough for the younger Avi. The disdain for his type of Jew came from the top in Israel. Prime Minister David Ben Gurion referred to Oriental Jews as “savage hordes,” and the Foreign Minister Abba Eban at the time spoke of the need to “instill in them [Oriental Jews] a Western spirit, and not let them drag us into an unnatural Orient.”

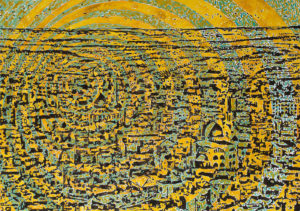

Shlaim moved to Israel in 1950 with his mother and siblings. Although I consider myself to be fairly well read on Palestine/Israel, I realized reading these sections of Three Worlds that I had read few books — historical, fictive or otherwise by Israeli writers—that described Israel as a place, a society or as a community, which did not have the Palestinians as a point of reference, however peripheral. Writing from the eyes of the child that Shlaim was, the Palestinians simply do not figure in his depiction of this tenuous, heterogenous new state project into which he was forced to adjust. Palestinians in my experience, have been forced into an obsession with Israel, particularly for those living under occupation as Israeli law and military control every aspect of their lives. Meanwhile, Israel has educated its people to not see Palestinians at all.

This absence left me wanting a sequel memoir by Shlaim, one that explains the process of brainwashing as he experienced it, his reflections on it now and most importantly, the encounters and thought process by which he became the person he is today. I can’t imagine that the process of becoming aware of the lies one has believed in was either comfortable or easy. Being a member of a minority is likely to have assisted his ability to do so, encouraging as it does the ability to critique the mainstream and think freely. European nationalism and Zionism uphold collective identities with a common purpose. Three Worlds not only reveals what devastation such political ideologies can wreak upon those deemed too extraneous to their projects, it also reveals the power and integrity that an individual in the minority is capable of.

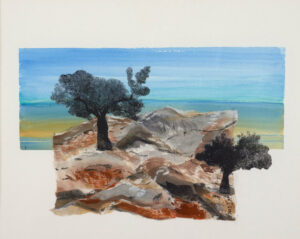

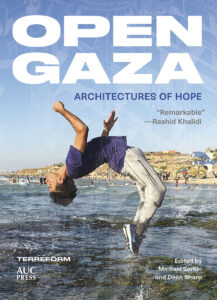

I was also intrigued to read in Three Worlds of the methods used to settle new Jewish immigrants across Israel: force and restrictive permits policed them into place. Few wanted to live outside the cities and had to be pushed into the countryside, a terrain that had been forcibly depopulated of its Palestinian inhabitants, where approximately 500 villages had been destroyed. “Most olim wanted to be in or near the big cities in the centre of the country, but often ended up in remote rural places in the arid Negev and in the border areas. Some physically resisted being dumped in the new destination that was decreed for them.” A poignant example is of a bus driver who “sometimes came home late at night in the early 1950s with bloodstains on his shirt following scuffles with immigrants who refused to get off the bus.” When one has read of the accounts of Palestinian refugees risking death to cross the borders (criminalized by Israel’s Prevention of Infiltration legislation from 1948) in order to pick the fruit on trees on their land, the children who were now in the fifth generation born in refugee camps who still know the name of the — often now destroyed — villages that they came from, with the women continuing to use the distinctive colors and threads of their villages in their tatreez embroidery, not to mention the prose, poetry and art lamenting the loss of the land, it becomes all the more painful to read of one population being forced out of a territory by gunpoint, for another population to be forced into it in the same way.

The evil of forcible population transfer, which lies at the heart of colonialism and Zionism, is documented in Three Worlds, from the legislative decrees, secret agents and bomb plots to the social and psychological damage done to children and families. Racist ideologies underpin the replacement of one population by another. They rely on underdogs who are the “other” to sustain themselves and their prejudices transmute across societies, like a contagion, becoming increasingly militant as they become more fragile and as they move away from their founding myths.

Shlaim is the narrator of this memoir, but there is also a magnificent heroine in Three Worlds and some antagonists who are exposed with cunning by the book’s narrator, as assisted by the heroine, Avi’s mother. Saida Shlaim, who died at the age of 96 in 2021 was a woman who developed a passion for swimming in Baghdad. “She was increasingly adventurous in the waters of the Tigris, jumping off bridges, doing stunts and participating in competitions. On top of this, she pursued horseback riding and dancing.” Married in her teens to a man far older, hers is in part a riches to rags tale. Her resourcefulness, intelligence and strength carry the first chapters of the book, as they carried her family from their mansion on the banks of the Tigris to a small apartment in “dreary” Ramat Gan and the “pigsty” that she described as Israel. The strength of her recall, desire for precise detail, and her sheer tenacity are formidable. The diamond rings she smuggled out of Baghdad (the memoir is filled with One Thousand and One Nights references; moving jewels and carpets being some of them) saved the family from some of the humiliations most Arab Jews had to live through upon arrival in Israel (such as being sprayed with DDT and being made to live in leaky tents in the desert). The antagonists are Israeli Mossad agents who disclose in a series of boasts and admissions to the ever charming Shlaim the historian, their role in terrifying and driving the centuries old Jewish population of Iraq into exile. For the details as to both how they did it and how Avi and his mother got them to admit to it on record, you will have to read this compelling, informative and touching memoir.

Existe este libro en espanol ? si es asi donde lo conio en USA