This essay is excerpted from Being There, Being Here: Palestinian Writings in the World (Syracuse University Press, 2022) and is published here by special arrangement. “Dedicated to the memory of Shireen Abu Akleh, one of the most relevant and important Palestinian voices of late. Killed on 11 May 2022 — shot in the head, probably by some kid in a uniform who’s been taught his entire life that this is his calling.”

Maurice Ebileeni

In 1868, the unknown “nine years old or thereabouts” Konrad Korzeniowski, “while looking at a map of Africa of the time,” put his finger on “the blank space then representing the unresolved mystery of the continent” and promised himself, “When I grow up, I shall go there!” It seems now to be common knowledge in literary circles that many years later, Korzeniowski’s adult alter ego, Joseph Conrad, would immortalize this call in Heart of Darkness through the fictional Charlie Marlow before he engages on his journey to the Congo and confronts the “dangers” of the continent. I am beginning with this reference to Conrad because while writing Being There, Being Here, Marlow’s words resonated to me in Erez Kreisler’s (former head of the Misgav Regional Council in the north) descriptions of the Galilee in a recent Haaretz article about the monitoring of Israeli housing regulations to maintain a dividing line between the area’s Jewish and Arab inhabitants. Kreisler, who claims to be “in favor of life together, but on the basis of some sort of structure and framework,” explains that he arrived in the Galilee in 1989 when “the image of the Galilee was that of an enfeebled, wretched, even dangerous region.”

I moved to Israel in the mid-‘90s as a young adult and strange as it may sound now, I simply did not think about the political implications of what it would be like to live in Israel as an Arab.

With these few words, Kreisler transformed the birthplace of my parents, my wife, and my three children into — to put it in Conradian terms — “one of those dark places on earth” and severely inflamed my awareness of my status as a “person of color.” It is not to claim that I had not stood face to face with “otherness” before. Still, for many years, the repercussions of those encounters were remarkably faint. Born and raised in Copenhagen by Arab immigrants, my so-called “color” was a constant mark of distinction, but it was the ‘80s and my presence among my Danish peers was then viewed as “exotic” rather than “threatening.” I grew up as a native speaker of Danish, a devout lover of leverpostej and remoulade, and a loyal fan of Dennis Jürgensen’s youth novels. Surely, I was occasionally reminded of “where I originally came from” insofar as my Danish education could, of course, never be fully realized due to my “exotic” roots. I can, however, not recall a single instance of such evocations that stuck or caused any recognizable long-term damage (if such a thing is possible). It was a relatively happy childhood and, although I was rarely targeted, it is only in retrospect that I understand the severity of derogatory colloquialisms such as “fremmedarbejder,” “indvandrer,” and “perker.” During those years, I possessed an innate ability to brush off the impact of such phrases — that same ability that I, in adulthood, have further honed to ward off the tremors of terms and expressions employed in the mainstream Israeli discourse regarding the country’s Arab citizens (the community with which I am affiliated today).

I moved to Israel in the mid-‘90s as a young adult and strange as it may sound now, I simply did not think about the political implications of what it would be like to live in Israel as an Arab. My decision was probably based on wonderful memories of summer vacations spent in Tarshiha as a child — of my mother waking me up when we’d arrive at the entrance to the town after a three-hour long ride from the airport — and of when we would ascend the curvy main street past the mosque, the Roman Catholic church and then the Greek Orthodox one, before we reached our destination — the upper quarter of the village where both my paternal and maternal families resided and where we would stay for the next four weeks.

The glamor of the signing of the Oslo Agreement was still at large in the ‘90s and political activity on the mixed campus in Haifa appeared more or less civilized. The controversial (and today exiled) Arab intellectual and politician Azmi Bishara was being courted by the Israeli media as the next big thing, and this first actual encounter with Israel outside Tarshiha convinced me that the place seemed by and large habitable. In Denmark among my peers in the ‘80s, my “exotic” origins were perhaps rooted in the worlds of Arabian Nights; in Tarshiha among relatives and friends, I had always been “al-danimarki” (the Dane); and now in Israel, a political climate was about to educate me into becoming the Arab. This identity has been a far cry from the one I was allotted in Copenhagen and, I have to admit, it took me some time to understand the trouble I had got myself into by moving here, and worse, the trouble I am now passing on to my sons in raising them here.

I became a student of English literature at the University of Haifa where I completed both my BA and MA. I then moved to the Hebrew University to pursue my doctorate where I later also became a postdoctoral fellow and stayed for another three years, before returning to Haifa, this time, as a lecturer. It’s been quite a journey and I have been fortunate to have met many wonderful people along the way but sometimes when I find out that I still, to till this day, need to answer questions by “well-meaning” individuals about if I am the first person in my family or village to receive a Ph.D. and so forth, I cannot but pause and wonder. Such questions, as you might understand, position me in an Israeli Orientalist discourse of the so-called “pioneering” Arab citizens — the first Arab beauty queen in Israel, the first Arab winner of the Israeli version of Masterchef, the first Arab minister in an Israeli government, the first Arab lecturer of literature in an Israeli English department, and perhaps sooner rather than later, the first Arab head of the Israeli Mossad. Seeing myself through the eyes of these “well-meaning” individuals and the eyes of the establishment in general, I have started to understand, or perhaps imagine, that despite of everything I might appear as nothing more than — to return to Conrad — “an improved specimen.”

At this point, I will take a chance by making a sharp turn toward the genre of science fiction. Some time ago I read the short story “Rachel” by Larissa Lai. Rachel (the Chinese-American protagonist) is unknowingly — for those familiar with Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner from 1982 — a replicant (that is, a bio-engineered being which is identical to humans except for its superior physical strength and its inability to understand emotion). Lai’s story focalizes events through Rachel’s perspective and begins with the scene from the movie when she is being interrogated by a retired blade runner (the Harrison Ford character) in her father Eldon Tyrrell’s presence. Deckard is conducting the Voight-Kampff Test to find out if Rachel is a replicant and following a long and thorough investigation, Rachel is asked to step outside. As she leaves the room, Rachel accidentally overhears Deckard ask her father: “How can it not know what it is?” She barely hears the words, but she hears them well enough to discover that she is indeed a replicant and well enough to contemplate for the rest of the story what it means to be an artificial being — and I should add, an artificial being with a Chinese-American identity. The reason for going here is because I was struck by the policeman’s question, perhaps in the same way Rachel was: “How can it not know what it is?” Being the constant other as a second-generation immigrant in Copenhagen, or as the foreign cousin among relatives, or as an Arab in Israel, I cannot honestly say what “it” (this otherness) exactly is or that I have ever consciously thought about it as other until only a few years ago. However, I can say that Erez Kreisler’s words cut through loud and clear and “while I still do not exactly know ‘what’ I am,” I am slowly learning what discourses of power (and also resistance) seem to “know” about me.

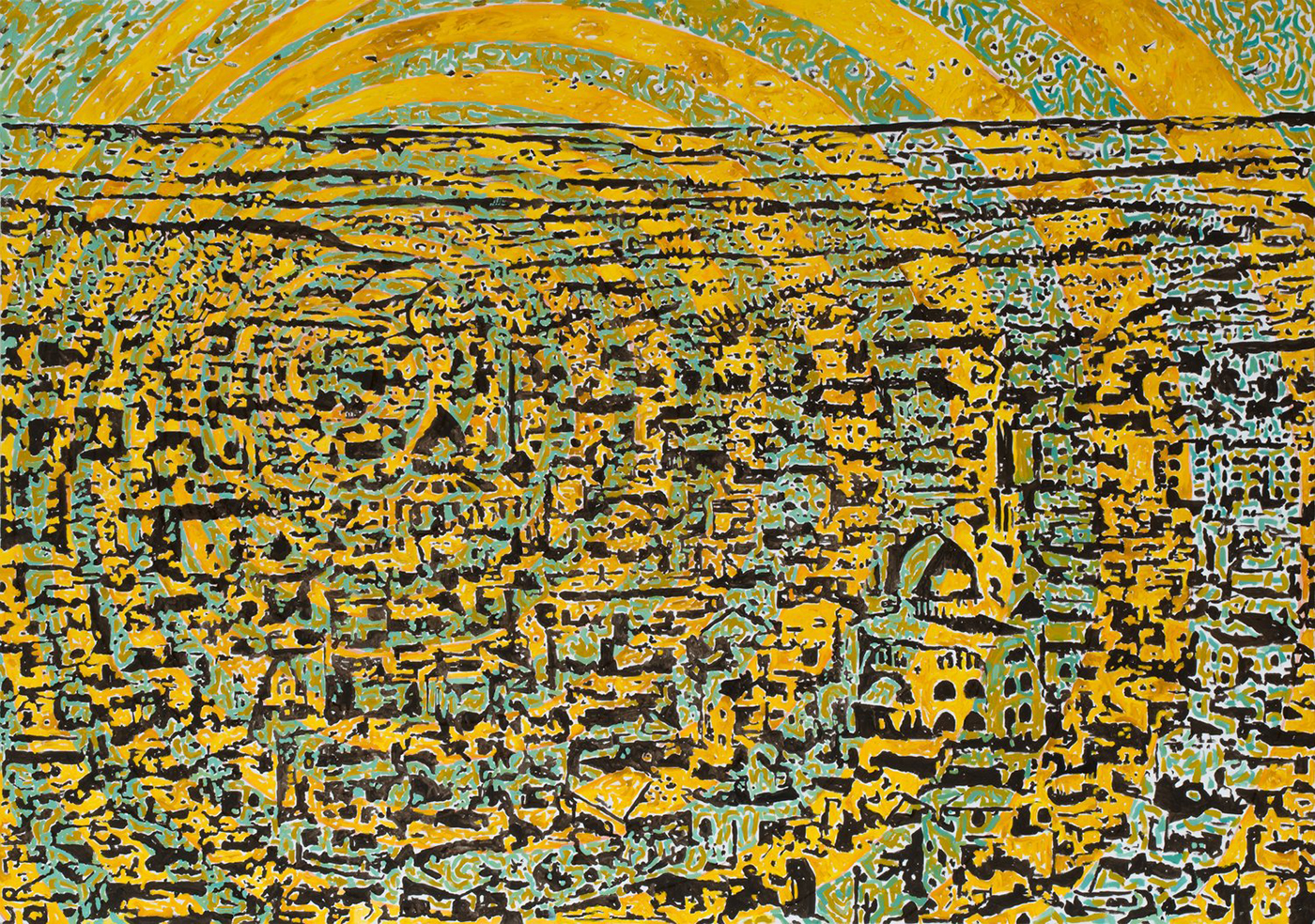

My modest library in Tarshiha somewhat represents this position. It would perhaps be a relief for some (or not) to know that it does not only hold titles in Arabic. In this “enfeebled, wretched, even dangerous region,” there exists a private book collection comprised of titles in languages such as Hebrew, Arabic, Danish (and other Nordic languages). The majority of the books are in English — my language of profession. The collection is a far cry from Jorge Luis Borges’s universal library, but kind of reminiscent of Mustafa Saeed’s — from Tayeb Salih’s haunting novel: Mawsim ‘al-Hijrah ‘ila ‘al-Shamal (Season of Migration to the North, 1966) — library that remained concealed in the village of Wad Hamid next to the Nile in northern Sudan before it was burned down.

Hidden away, far from the Israeli reality comprised of the kibbutzes, the moshavs, and the developmental cities in the Galilee, in a lonely house on the south side of the Mujahed hill in Tarshiha, among olive groves and sheep, my collection of books not only represents a personal story, but also those by Palestinians and their descendants today living in different locations around the globe. It holds names such as, among so many others, Anton Shammas, Naomi Shihab Nye, Diana Abu Jaber, Nathalie Handal, Susan Muaddi Darraj, Randa Jarrar, Ibrahim Fawal, Selma Dabbagh, Lina Meruane, Mischa Hiller, and Yahya Hassan – writers who have authored texts that more-or-less express my predicaments regarding identity in ways which Arabic texts could not sufficiently do.

The point of describing this journey is not to present a coming-of-age narrative and to make some ultimate declaration about having finally arrived. The purpose is rather to make room in the Palestinian story for people like myself – and also to mark a critical position that will allow a comprehensive study of the fluid condition of Palestinian literary imagination in both Israel-Palestine and the world at large.

Since Being There, Being Here is to a great extent a study of Palestinian literature in languages other than Arabic, a personal note on language is warranted here. Arabic is unconditionally the Palestinian national language. However, for many, it is no longer their mother tongue. My own relationship with Arabic remains vexed. Today, I enjoy an advanced level of proficiency, but I still find it emotionally challenging to either write or read in Arabic. I rarely pick up an Arabic novel (despite my profession as a professor of literature) and feverishly avoid writing in Arabic. Any such direct engagement immediately brings back memories of my uphill battle learning to read and write Arabic during those early years growing up in Copenhagen. It was a battle I did not choose. It was forced upon me by my parents every evening when I had completed my Danish school homework and they would wait for me with the Arabic textbooks to teach me the basics. It was forced upon me with every lash of the cultural whip at my preference for speaking Danish at home rather than Arabic — at every transgression of the conventions of our Arab ways.

I do not believe that my relationship with the Arabic language is unique. It is telling, I think, of how second-generation immigrants relate to their parents’ heritage in general. We spend a lifetime negotiating, occasionally accepting, and mostly rejecting what our parents represent. I have yet to meet someone who has not stood next to their parents at some supermarket, embarrassed while listening to them speak in the local foreign language that is native to their children. In addition to language, my rebellion against my parents’ heritage became most vocal during epic arguments over food. While I have always adored my mother’s mujadarrah, mloukhieh, and maqloobeh, I constantly made sure to express my preference for the Danish cuisine in reply to her lectures of how much better and healthier the Arabic one was in comparison to anything else in the world. My biases against everything Arab became increasingly radical. I wanted to assimilate. As far as I was concerned, I was already Danish — although with the “exotic” twist — while my parents offered what seemed to me the option to be an immigrant. At the time, I was completely ignorant of the ongoing public discussions about defining “Danishness” and the general notion that “brown skin” could never become genuinely Danish. In my uncompromising adolescent battles against my parents, it was “me” against “them.” Although I today live in Tarshiha with my family and my parents have by now retired and moved back here as well, I cannot honestly claim that these battles have ended. They may be different in character, but the substance of our constant arguments remains more or less the same, and I, today a middle-aged man, adamantly continue to express my preference for everything Danish and dislike for everything Arab in their presence.

My family and I frequently go to visit my former homeland. My sons and my wife do not speak a word of Danish — except for sometimes intentionally mispronouncing things they hear me say for the purpose of making fun of me — yet they have developed a bond with the place and generally look forward to our trips. I selfishly enjoy adding this dimension to my sons’ upbringing, in the hope that they will grow up to become less localized individuals and better prepared for our increasingly globalized world (with a twist of some Nordic culture). However, I also recognize as we walk through the streets of Copenhagen that the place no longer houses the notion of home for who I have become in Israel. I am still intimately familiar with every minute detail and nostalgically savor the smells emitted from the butchers and bistros. I make it a ritual to walk to the local bakery in the morning to pick up Politiken, a spandauer, and a coffee. I enjoy shopping for Danish groceries in the local Netto, but I am also aware that my head is elsewhere at this point in my life. At the end of our trip, we return to Israel, to Tarshiha, to the awful “Nation-State Law,” back to claim our position in the Arab minority among those individuals who miraculously managed to survive and stay on their land despite impossible odds in 1948.