Rebecca Allamey

When my parents told me as a child that I was white, I believed them. However, as a second-generation Iranian American living amongst a white majority, I soon came to realize that my kind of white is not the same kind as those who espouse white supremacy.

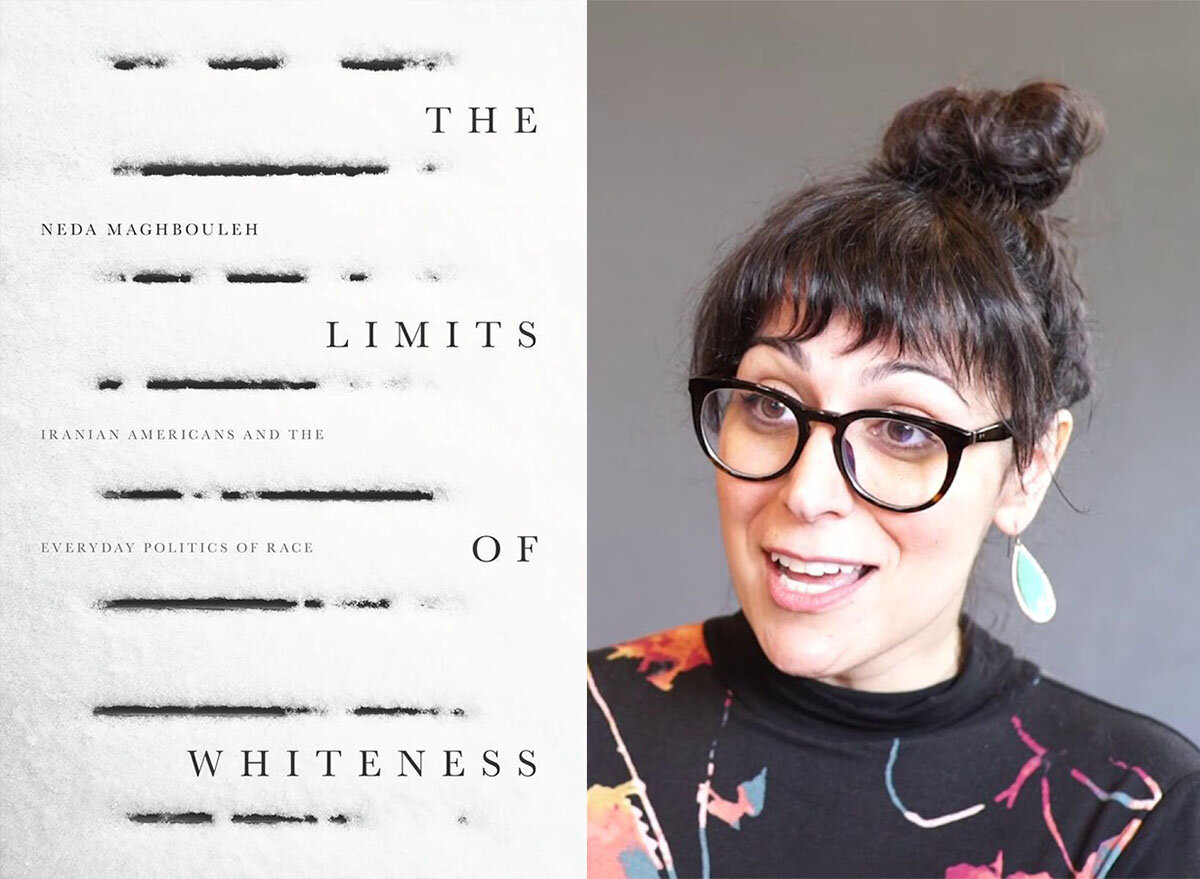

When I first read Neda Maghbouleh’s The Limits of Whiteness: Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race I felt as though the author was speaking directly to me and my experience. An associate professor of Sociology from the University of Toronto, Maghbouleh explores a key paradox in the racial identity of Iranian American immigrants. Native Iranian self-identity, supported by genetic lineage, interestingly aligns with a U.S. classification system that carelessly groups most Middle Eastern immigrants together with a white majority dominated by Europeans. However, despite this internal and external white-washing, the lived experience of Iranian Americans constantly reinforces a notion of non-white otherness.

Maghbouleh’s thought-provoking work from the sociological perspective offers a fresh take to explain how racial identity of ethnic groups is often defined through social interactions, rather than external or internal classifications. Based on years of ethnographic research and interviews with 80 second-generation Iranian Americans, the author engages the reader through artful story-telling that reinforces how the descriptions of racial issues play out at the micro-level. Focusing on the experiences of second-generation Iranian Americans, Maghbouleh brings to life the narratives of those who have to deal with the issues of contradictory racial definitions of growing up in America.

Racial Self-Identity

For many Iranians living in this country whose parents made the necessary sacrifices to immigrate to America, life is a contradiction where elements of cultural and ethnic identity are preserved, while the presence of an independent racial identity are largely ignored. Second-generation Iranian Americans are unique because they can often blend into American society culturally and linguistically in a way that is not feasible for native Iranians.

Iranians who immigrated to America around the time of Islamic Revolution and the hostage crisis were faced with a great deal of suspicion and even anger, such that they often adapted by camouflaging themselves with name changes and trying to pass for other ethnicities — lying about heritage became a form of self-preservation. One way that this phenomenon broadly occurs across many immigrant groups upon being granted U.S. citizenship is the encouragement of adopting American names that serve to facilitate assimilation in American society. My parents Mojtaba and Mehri, who immigrated to the U.S. in the late 1980s, will commonly introduce themselves to Americans as Michael and Megan, the names they were encouraged to legally adopt upon becoming naturalized citizens.

Despite the incursion of racial episodes into daily life for Iranian immigrants, these experiences are often concealed from the younger generation growing up in this county. Maghbouleh shares the story of Yara, who aptly describes how racial discrimination is often a non-topic in the Iranian-American household while also being a hyper-visible, ever-present issue in society:

“In general, I don’t know to what extent [my parents] even want to bring [being harassed] up with me. But it’s like, obviously, they face it. If I face it, and I have no accent, but my mom and dad have really thick accents, especially my mom, it’s more prominent. If most people can tell that I’m not American, then what does that mean about them? In a way, maybe I’m getting less of it. And they’re not going to tell my brother or me about it.”

Many Iranian children born in the United States learn, either explicitly from their parents or implicitly as part of growing up in this country, that they are classified as members of the white racial majority. However, the legal, biological, and (sometimes) internal absence of race coexists with experiences of racialization in society. Maghbouleh illuminates this duality through the eyes of second-generation Iranian American youth across the country. While the specific details of each story are unique, they share an underlying theme where Iranian Americans are caught between formal legal invisibility and informal ethno-racial extra visibility. The racial discrepancies faced in society force Iranian Americans to grapple with these issues without the sensitivity typically engendered by other minority racial groups.

Maghbouleh writes, “Contrary to what they hear from elders… second generation youth are mostly skeptical and often critical of self-identifying as white. If they once believed it, their more incontrovertibly white peers have disabused them of the notion. Instead, Iranian-American youth describe a profound conflict between the white identities asserted within their families and the stigmatized racialization they (and their families) actually experience in the world outside the home.”

In an interview with the LA Times, Maghbouleh notes that when her book first came out in 2017, older Iranians did not agree with or understand her desire to explore Iranians’ complicated relationship with whiteness. After all, they were taught in school that Iranians descended from the Aryans and were thereby the original white people of the world. Recent global events, including the Muslim travel ban, have shifted this belief and forced Iranian-Americans to grapple with the realization that despite underlying self-identity and legal status, they are not viewed as white in a country fragmented by racism.

Racial Classification and Erasure

For most groups in society, ethnic and cultural identity falls under the umbrella of racial identity. For Iranian Americans, embracing a rich cultural background is in direct conflict with the monotone racial classification that is forced on them. In an interview with The Iranist, when asked why it is problematic that the U.S. Census Bureau decided not to include a Middle Eastern or North African (MENA) category on the 2020 census, Maghbouleh explained that the MENA community has long viewed that “… being lumped together into a white box [is] an erasure of their community.” This type of racial erasure is typical of the views in Trumpian America.

The ramifications of belonging to an unrecognized ethno-racial category include being denied minority rights and equal access to material resources. However, the relationship that Iranians have with racial classification is one of distrust, often avoiding filling out government census forms in a way that would draw attention to their other-ness. Many sociologists attest that race is a made-up social construct, but it is clear that for Iranian Americans, it continues to have very real consequences.

Historical Basis of Iranian Race in America

So how did Iranian Americans end up in this position of racial contradiction? Prior to legal changes in the mid-1900s, the Naturalization Act of 1790 dictated that only people who were officially classified as white were able to be granted US citizenship. Before large-scale Iranian immigration into the United States, the Iranian ethnic group was already being implicated in other groups’ racial struggles and referenced as an inflection point in attestations of whiteness.

On the one hand, Eastern Europeans and other Middle Easterners pointed to Iranians and Zoroastrian practices an example of non-white belief systems to distinguish themselves in the hopes of acquiring US citizenship. Conversely, South East Asians and groups from the Indian subcontinent referenced overlapping genetic lineage with Iranians to cast themselves as sharing white heritage in the eyes of the law. To characterize this duality, Maghbouleh coined the term “racial-hinge” to describe Iranian racial identity being somewhere between white and non-white, capable of swinging back-and-forth across the hypothetical divide to placate the needs of the arbiter.

When Iranian immigration to America became more common after the Iranian or Islamic Revolution (1978-1979), Iranian racial classification was solidified as being on the white side of the divide. However, this legal classification has not inherently protected Iranians from racialization and stigma within American society. American sentiment towards Iran deteriorated following the revolution and was further exacerbated by the Iranian hostage crisis and associated media coverage. According to a 2016 Gallup Poll, by the year 1990 over 90% of Americans expressed negative feelings towards Iran.

Unfortunately, Americans’ feelings of animosity are not limited to the Iranian government but are often spread across the entire ethnic group. Maghbouleh cites fellow sociologist Mohsen Mobasher’s attestation that, “No other immigrant group…from an ‘enemy state’ has been so politicized, publicly despised, stigmatized, and traumatized by the U.S. government as have Iranians…No other immigrant group from a former ally country of the United States has lost its positive social image so quickly and has been so misrepresented, stereotyped, misunderstood, and made to feel so unwelcome despite its overall high socioeconomic status and record of accomplishment in a short period of time as Iranians have.”

Citing the lawsuit Pourghoraishi v. Flying F, Inc. (2006), Maghbouleh details how Iranian-Americans fall victim to a legal classification that disagrees with lived reality — and is further complicated by the apprehension that Iranians feel in bringing attention to their other-ness. In the case, Pourghouraishi experiences what seems like a clear case of racial discrimination at an Indiana truck stop, the Flying J, where he is refused access to the restroom. The case hinged on whether plaintiffs could prove that Flying J perceived Pourghouraishi’s race as the basis for the discrimination. Plaintiffs asserted that, “any reasonably aware and knowledgeable person would have identified Mr. Pourghouraishi as middle eastern [sic], both by his appearance and speech.” However, the case fell through when Mr. Pourghouraishi himself took the stand and repeatedly denied that he looked different from anyone else at the truck stop and that there was no inherent way for defendants to identify him as from a different origin than the United States.

It is difficult to assess the extent to which Mr. Pourghouraishi was acting in his own self-interest during this case. On the one hand, if he had simply testified that his appearance preempted the discrimination, the underlying cause of racial bigotry would have been supported. But why was Mr. Pourghouraishi forced to state this obvious racial delineation that runs contradictory to the federal categorization? By being subject to a classification system that disagrees with societal portrayal and emotion, Iranian Americans have fallen victim to racial loopholes, where harm is incurred due to a lack of distinct racial identity.

Perception of Iran in American Society

Due to the complex historical relationship with white Americans and the negative portrayal of Iran in western media, Iranian Americans today deal with direct and indirect discrimination that is typical of racist ideology. In one passage, Maghbouleh introduces the reader to Donya, the daughter of Iranian American immigrants who faces racially motivated discrimination at school. Donya shares her experience:

I thought I was ugly. I go to a mostly white school. And kids would say, “Wow, you have a unibrow. You have really bushy eyebrows. You’re so hairy: you’re a gorilla.” And I would be like, “Okay dude, I know. Thanks for the reminder.” Society kept reminding me. I told my parents, “The kids in my class are making fun of me, and they’re calling me gorilla, making ‘ooh ooh’ noises. They said Bin Laden is my dad.”

This made me wonder how many Iranian Americans children in school have been bullied and unfairly accused of supporting Bin Laden and Muslim extremism. I know I have. Despite being an elementary school student at the time, my optimistic relationship with this country fundamentally changed after 9/11. My peers did not shy away from calling me a terrorist and my teachers did not seem to mind either, even taking part in this mis-direction of racial bigotry. These issues ranged from condolences on the passing of “family members” (after the execution of Saddam Hussein) to being questioned on the direction of oil prices from a teacher who found humor in making these types of associations about my heritage.

I remember confiding in a POC who held an administrative role at the school, asking for help navigating the racial dynamics that were impacting me. Without confiding his own personal experiences with race, he reinforced the idea of observable vs. unobservable racial differences. In his mind, I was lucky to have an American name and a lighter skin that could enable me to pass as Italian or Greek. After all, wouldn’t it be easier to avoid the issue of racial differences that lead to discrimination? While racial bias is often correlated with the darkness of one’s skin, the Iranian experience in society is more akin to an on/off switch where simply knowing or not knowing of the existence of Iranian heritage plays a major role in any potential discrimination or lack thereof.

One of my worst memories dealing with racial discrimination was when I was forced to change my homeroom class half-way through high school when my teacher found out I was of Iranian descent. I will never forget his utter disgust and his promise that I would be out of his class by the next day. Of course the change happened over night forcing me to reconcile with the embarrassment. In my new Homeroom class, I revealed why the sudden and rare change occurred, to which my new teacher said, “yeah, he is like that. That’s just who he is.”

This kind of treatment continued even outside of academia. In college I was invited to my boyfriend’s family’s house for dinner. I remember the excitement I felt about being invited as I sat down to join them. Knowing that my parents were Iranian immigrants, minutes into meal his father asked, “So did your dad used to ride a camel to school?” While clearly a misguided attempt at humor, this experience is representative of the dilemma faced when dealing with racially-motivated statements. Either laugh along at the expense of my heritage or stand up for myself and be viewed as the aggressor who can’t take a joke. I stayed silent.

Portrayal of Iran of Western Media

Maghbouleh touches on the underlying sentiments that many Americans feel towards Iran by referencing an episode of the popular game show Family Feud (perhaps coincidentally aired on 9/11 in 2012) where contestants were asked to name a place where no one would want to visit. Alongside reasonable answers such as “jail” and “hell”, two specific geographic locations were included as acceptable answers: Iran and Siberia. Maghbouleh aptly explains that while the notion of visiting Siberia is related to broader concepts (cold, vast, remote tundra), the idea of Iran being an unattractive destination is directly tied to the politics of the country, and ultimately, its people.

This example illustrates the misconceptions that Americans have about Iran while also reinforcing the conflation that occurs when negative sentiments (that may fairly be cast against the Iranian government) are spread over the country and people as a whole. For any second-generation Iranian American watching the episode, the inclusion of Iran is likely to have been quite a contradiction to their personal perception. Maghbouleh comments on this discrepancy by observing that “Second-generation Iranian American youth are, for the most part, born into homes where Iran is romanticized while growing up in a country, with few exceptions, in which Iran is stigmatized.”

The confounding of negative western stereotypes onto Iran as a destination rang especially true based on my experience. As someone who is lucky enough to have visited the native country of my parents and ancestors, I have wonderful memories of my time in Iran and being immersed in the most beautiful landscapes, awe-inspiring architecture, and delicious cuisine. The Iranian stereotypes that speak to me and my experience are based on the graciousness and hospitality of its people and are in direct opposition to those encountered in the western world.

Less explicit negative examples in the media that may seem harmless or light-hearted can unfortunately impact or color a naive viewer’s perception of Iran. In an episode on the food competition show Chopped that featured former military members, contestants were tasked with making a meal using Persian food/drink staples “torshi” and “doogh”. The comedic relief occurred as the contestants tried small samples and expressed their disgust while the less tone-deaf judges explained that these commodities are treasured in Persian cuisine. Similarly, doogh was the main subject of one of the most watched videos on Barstool (posted September 2020). In the video, many people are seen tasting doogh and most of them reacted extremely poorly by gagging and spitting up the drink (not to mention repeated careless pronunciation of the country of origin as “eye-ran”). Seeing one of my favorite drinks ridiculed in a way that felt racially motivated under the guise of humor was disheartening, and I wasn’t alone. The video was the subject of contention on Twitter and one user captured the essence of my concern, commenting that this type of activity only serves to “light a xenophobic fire.”

In the summer of 2012, New York Times contributor Nicholas Kristof traveled to Iran and upon his return wrote in his report named Pinched and Griping in Iran (June 2012): “…with apologies to the many wonderful Iranians who showered me with hospitality, I favor sanctions because I don’t see any other way to pressure the regime on the nuclear issue or ease its grip on power. My takeaway is that sanctions are working pretty well.” While one can debate the utility of economic sanctions to achieve a political goal, Kristoff’s lack of humanity towards Iranian people in favor of promoting national security was a disheartening moment that further contributed to the dehumanization of Iranians.

While most portrayals of Iran in modern media have been negative and stress cultural differences, the late Anthony Bourdain provided a different perspective in a 2014 episode of his show Parts Unknown. Traveling to Iran to explore and indulge in the local cuisine, Bourdain centered the episode around exposing the striking misconceptions that westerners have of Iranian people, showcasing the friendly and hospitable nature of the majority of the Iranian public. The episode culminates with Bourdain being invited to dinner in an Iranian household and being treated to a home-cooked meal, serving to show American viewers that the stories they have been told about terrorists and bombs are the product of weaponized political messaging more so than a reflection of cultural reality.

The typically negative portrayal of Iranian culture in the U.S. media has a direct impact on the way Iranian-Americans are viewed and treated in society. Growing up whenever I had a birthday party friends would come to me afterwards and say, “Wow! Your family is so much different than I thought.” While meant to be some type of compliment that we’re “not that bad,” it was a harsh reminder of how misunderstood and stigmatized Iranian culture has become. As a young child, I was forced to grapple with difficult questions on my family’s place in American society: What did they think about us before that led to such a surprise when in the presence of such a normal happy environment, similar to their own home life? Did they not think we were as human as they are?

Lived Experience – Life Defines Racial Identity

In some of the most gripping passages in The Limits of Whiteness, Maghbouleh details episodes of direct discrimination that Iranian-Americans have experienced in this country. When the memory of a student’s experience in a 5th grade classroom is rendered, Maghbouleh has the reader feeling the pain and struggle that is all to familiar for second-generation Iranians:

“Sima took a deep breath. ‘I’m never going to forget this,’ she said, before describing what happened next. She delivered her campaign speech and reeled with adrenaline and nerves. Then a boy named Tommy stood i[ at his desk to ask her a question. ‘In front of the entire class,’ Sima remembered, he said, ‘So if you win, are you going to make us say the pledge of allegiance like this?’ while taking his right hand from his heart and putting his index finger across his eyebrows. ‘He was making fun of my unibrow,’ she remembered. The room became electric to her as giggles erupted out of all her classmates. All eyes were on Sima to see how she would react. No friends stood to defend her, nor did the teacher interject with any sort of admonition to Tommy…”

Maghbouleh tells the story of a Latino man named Miguel who was attacked by white men, in his own words, “because he looked Iranian.” The mainstream media often characterizes discrimination against Iranians and other Middle Easterners as “anything but race,” pointing to ethnic, cultural, or linguistic differences as the motivating factors. However, the case of Miguel’s attack and associated “racial mis-recognition” shows us that the ethnic/cultural identity of Iranians is not a necessary component to ignite animosity or violence. As Maghbouleh concludes, “That these types of ‘racial mis-recognition’ cases consistently involve white Americans enacting violence against racial minorities whom they inaccurately perceive to be Iranian points to an on-the-ground cognitive racial status of Iranians as not-white, at least in the present-day white American imaginary.”

Although perhaps not as straight forward as police brutality against African Americans, the discrimination that is felt by Middle Easterners at large cannot honestly be construed as anything besides racially motivated acts of hate or ignorance. Viewing this typ

e of discrimination as a non-racial issue ignores the experiences of Iranian Americans who are imagined (and imagine themselves) outside the limits of whiteness.

Where do we go from here?

Second-generation Iranian Americans continue to cope with racial inconsistencies that complicate their identity and sense of belonging in the United States. With the freshly-elected Joe Biden in the White House, it is likely that the Muslim ban will be lifted through Executive Order shortly following his January 2021 inauguration. Although this will not change the past struggles for the people across seven countries impacted by the ban, it will hopefully represent a step towards reducing international tension. However, as discussed throughout, it remains to be seen if legal decision-making is able to permeate through to everyday life.

By engaging the reader with ethnographic evidence and captivating narratives, Neda Maghbouleh succeeds in The Limits of Whiteness: Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race by making a case for the new, radical idea that a white American immigrant group can (and ought to) have the transformative power to become brown. Acknowledging that the social construct of race has failed to adequately account for the Middle Eastern lived reality in this county is an important first step in developing practical solutions to establish an independent racial identity for a group of people who have been victims of racial loopholes for far too long.

With a historical legacy rooted in the glory of the ancient Persian empire and a presence informed by societal experience in the western world, Iranian Americans are poised to play a pivotal role in the continued development of their racial identity in American society.