A film plagued by myriad challenges, it’s almost a miracle Costa Brava, Lebanon was completed. “I think making the film became like an act of resistance.” —Mounia Akl, director

Meera Santhanam

“LEBANON, IN THE NEAR FUTURE,” reads the opening caption of Mounia Akl’s Costa Brava, Lebanon. The irony of the caption manifests itself almost instantly, as we hear sirens blazing in the background, disembodied voices issuing instructions through an intercom, and the rumble of a garbage truck. Slowly, the camera pans across the Port of Beirut, revealing a man with a mask, the twinkling lights of Zaitunay Bay, and the silhouette of smoldering grain silos, a living testament to the damage wreaked by the August 2020 port explosion.

This somber portrait is no fiction. Akl’s “near-future” Lebanon bears an ominous resemblance to the present, with the film’s opening sequence a stark reminder of the 218 deaths caused by the Beirut blast, the largest non-nuclear explosion in history, which wounded 7,000 others, displaced more than 300,000 people, and destroyed half the city. In less than a minute, we learn that this film is no dystopian fantasy; the face mask in the opening shot cues us to the myriad crises affecting Lebanon today, from the Covid-19 pandemic to the country’s garbage crisis and economic collapse.

The culprit? The film is unambiguous, illuminating the stench of corruption as it follows the story of the Badri family, who, having escaped the pollution of Beirut to the mountains, must determine whether to stay or to leave when the government decides to construct a landfill next to their idyllic hillside abode.

“Costa Brava was a movie that was set in 2030, but the reality of the country degraded so much that the dystopia I wrote was nicer than the reality of the country,” Akl told me over coffee on the evening of the film’s Beirut premiere. “So I just canceled that, and I said that it’s a movie about now.”

A Landscape of Crisis

Costa Brava, Lebanon, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival in September 2021, and was released on Netflix in November 2022, takes its name from Beirut’s Costa Brava landfill, which the Lebanese government opened in 2016 in an attempt to deal with a worsening garbage crisis. It is Lebanese director Akl’s first feature film and was Lebanon’s submission to the Academy Awards in 2022.

However, the film nearly didn’t happen. When a large amount of ammonium nitrate stored at the Port of Beirut exploded on August 4th, 2020, killing over 200 people and ravaging the city, Akl nearly called off whole thing. At the time of the explosion, she was in her office in Gemmayze, Beirut, working on the film’s pre-production with her crew. In a matter of seconds, everything changed.

“We went from a creative meeting filled with passion and love and excitement to looking for each other under rubble, wondering if we had all made it [out] alive,” Akl said in a TED Talk last year. While everyone in the crew survived, Akl’s cinematographer Joe nearly lost his eye, and many others sustained injuries as well. Walking outside on the day of the blast “felt like walking [through] the set of a movie I don’t want to direct or be a part of,” she recounted in her talk. “How can you even think about being creative or making anything at a moment where you feel like you’re living hell?”

Akl and her crew decided to put the film on pause, taking two months to grieve, process, and ultimately reevaluate whether or not to go forward with the project in the aftermath of the blast. The explosion not only killed 218 people and wounded 7,000, but also had a devastating physical impact on Beirut, damaging nearly 80,000 apartments (and displacing their inhabitants), and, according to World Bank estimates, causing over four billion US dollars of material damage, thereby exacerbating Lebanon’s financial crisis. Additionally, it had an immense psychological toll, with studies suggesting that approximately two-thirds of blast survivors suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Persevering in the Aftermath of the Blast

Still, against mounting odds, Akl decided to proceed with the film. “It was almost like a survival instinct,” she told me. “Something was driving me. I don’t know if I was running away from facing the trauma of almost having died and having to walk next to a destructed city with dead bodies.”

However, making the film transcended survival alone. “I think making the film became like an act of resistance,” Akl explained. Having lost loved ones and a large part of her city, Akl has described Costa Brava as a kind of love letter to Beirut, and a refusal to let the myriad crises afflicting Lebanon take away her passion.

“If the movie didn’t happen, then I would have lost everything,” Akl said. “At a moment where existing felt like an act of resistance, we felt like making this movie was very important because it would mean regaining agency and feel[ing] like they haven’t taken everything from us,” she reflected in her TED Talk.

Making the film was also a way of holding on to hope in a time where hope felt nearly impossible. “Most of the people [working on Costa Brava, Lebanon] wanted and needed to make the film, because they felt like: We need to have a reason to wake up in the morning, and creating gives that energy,” Akl told me. The film also helped to restore a sense of connection in the aftermath of the explosion. “At a moment where our societies are becoming more fragile and loveless, we were able to recreate […] warmth and love and magic,” she said.

Akl said that Geana and Ceana Restom, the twins who share the role of Rim, the youngest yet most outspoken member of the Badri family, were also a reminder to stay hopeful and hold on to a sense of wonder despite the current state of affairs in Lebanon.

Filmmaking Challenges

Creating Costa Brava in the aftermath of the explosion — and in the midst of the ongoing environmental crisis, financial crisis, and Covid pandemic in Lebanon — was not without its challenges. While the majority of the cast and crew opted to continue, one person decided not to proceed with the project, given the trauma of the blast.

Akl herself stated that while making the film was cathartic, she still needed to process the trauma of the explosion after filming was complete. “When I finished the film, I completely crashed, because my body told me you’ve repressed this for so long…but now you need to fall apart a little bit,” she said.

Making the film in Lebanon’s landscape of crisis posed its own pragmatic challenges as well. “I think the challenges we face are not creative ones, unfortunately. They’re related to a country that is falling apart and doesn’t support its artists,” Akl said.

When asked if she faced any challenges as a female filmmaker specifically, Akl acknowledged the role of the patriarchy, but highlighted that in Lebanon, her challenges are primarily practical ones, affecting men and women alike. “The challenges I’ve had to face are not related to my gender. They’re related to my humanity…[and] to the corrupt system we exist in,” she said.

The Role of Contradiction in Lebanon

Creating a film in the midst of an environmental catastrophe may seem like a contradiction, but it’s this very contradiction that underlies Costa Brava, Lebanon, and Lebanon itself. “Lebanon is a place […] where hope and despair coexist in really strange ways. It’s also a place where joy and sorrow are inseparable.”

Dealing with contradiction is not new to Akl. Splitting her time between Beirut and New York, she recognizes that dichotomies have shaped her relationship to Lebanon itself. “What I have between me and my home country is something I cherish, but it’s also a burden,” she says. Growing up in Lebanon, she felt as if she was constantly “on the verge of the worst.” “We live every day as if it were our last,” she says.

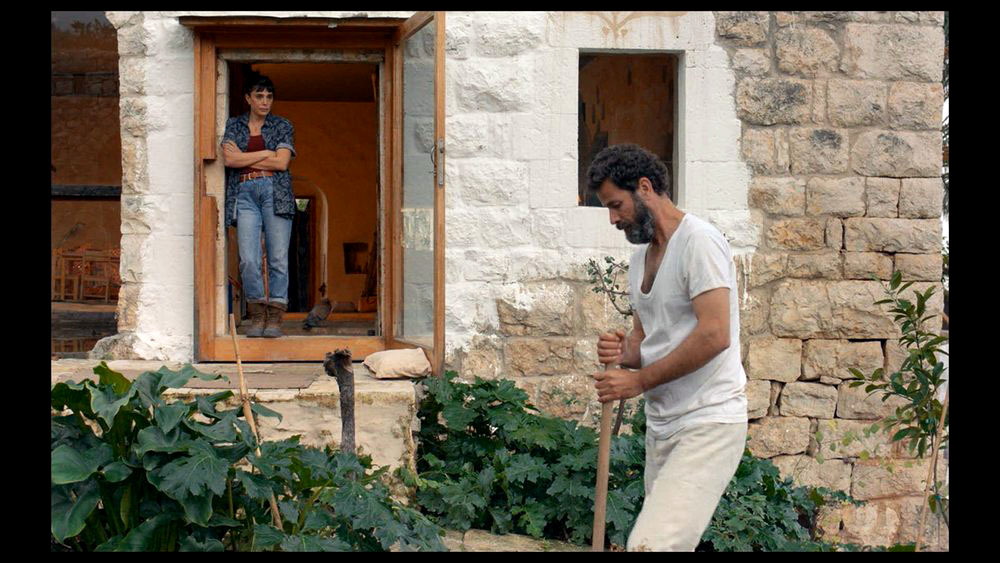

These contradictions recur throughout the film. Soraya (Nadine Labaki) and Walid (Saleh Bakri), the film’s protagonists, embody dualities, constantly debating whether to stay or leave after the authorities announce that they are building a landfill in the backyard of their bucolic mountain home. Soraya longs to return to Beirut, where she had a dazzling career as a singer, while Walid insists on staying in the countryside, too in love with what Beirut used to be to face the pollution and trash that now litter its streets, a reference to Lebanon’s 2015 garbage crisis.

Labaki and Bakri confront a variation of this debate in their own lives. Labaki, an internationally acclaimed Lebanese director in her own right, has said that she sees the film as a tribute to every person facing the dilemma of whether to leave or stay in Lebanon today, and that she identifies with the character of Soraya. Indeed, like Soraya, Labaki spends a portion of the year living with her family in a cabin in the countryside, where she grows her own produce, has chickens, and makes cheese from scratch.

“Every person who has left the country is feeling the exact same struggle,” Labaki said in a panel discussion of the film. “Do we go back and be part of the change and try to resist as much as we can, or do we choose to save ourselves and save our families and save our children and move away?” Labaki asks, her voice and Soraya’s merging into one.

Bakri, a renowned Palestinian actor, grapples with the same question in relation to his homeland. “For me, Beirut is Jaffa,” he said. “It’s something that occupies me all the time: leaving, staying, staying, leaving.”

Soraya and Walid aren’t the only characters who experience dualities in the film. Akl outlined how each character in the story is wrestling with his or her own contradictions. “You have a little girl who is completely free but actually completely trapped,” she said of Rim. “You have a grandmother who is full of life but at the same time is dying,” she said of Zeina (Liliane Chacar Khoury), Walid’s mother.

“The contradictions have become part of our programming as humans,” Akl told me. “Each of us has this dichotomy within us.” The film’s characters — and the members of its cast — each speak to that.

The Microcosm of Family

Ultimately, Costa Brava, Lebanon is a film about family told through the lens of the environment. While it is fundamentally a film about trash — detailing the lingering effects of Lebanon’s 2015 garbage crisis, which not only drive the Badri family out of Beirut, but follow them to the countryside — it constructs the family as a microcosm of the broader environmental and political tensions facing Lebanon today.

Akl calls the family “a mirror of the society” that the characters “are embedded in.” As environmental stresses escalate, so too do tensions within the Badri clan, with the proposed construction of a landfill next to their hillside home threatening their precious yet all-too-precarious harmony.

“I wanted to look at the country through the family,” Akl explained to me. “By looking at this family, by looking inward, you are actually looking at the world,” she added.

In fact, it was by examining her own family that Akl first arrived at the idea for the film. “The screenwriter in me was born out of observing my family,” she said. “I was very interested in talking about how by observing your own family, you are actually observing your own society,” she continued.

Growing up, Akl spent a lot of time at home because of the political situation in Lebanon. As a young girl, she came to realize that she could not divorce the happenings of the outside world from the happenings in her own home. “I always felt like the conflicts that were at home were always linked to how tense we were because of the outside,” she said.

“The pressure of the outside creates the fireworks inside,” Akl said. And fireworks indeed Costa Brava creates.

Akl is no stranger to writing stories that tackle both family and the environment. Her short film Submarine, which played at the Cannes Film Festival in 2016, also explores this tension, telling the story of Hala, a young Lebanese woman who cannot bring herself to leave when she is forced to evacuate her home because of the country’s garbage crisis. After wrapping up Submarine, Akl realized she had more to tell, inspiring her to create Costa Brava, Lebanon.

“You Stink”: Lebanon’s Garbage Crisis

While Akl’s film centers on the environment, its politics are unequivocally clear.

“Our existence in Lebanon is inherently political,” Akl said. In fact, the campaign that emerged against corruption in Lebanon in the wake of the garbage crisis in 2015, mobilizing more than 20,000 Lebanese to take to the streets to call for greater government accountability in addressing the trash crisis, was called “You Stink.”

“When [the garbage crisis] first started, you couldn’t walk […] the streets because the smell was very horrible,” Bruna Haddad, a 22-year-old Lebanese film student and aspiring producer, told me on the evening of Costa Brava, Lebanon’s Beirut premiere.

Akl, too, described the anger she felt watching her favorite landscapes in Beirut become “completely ravaged by garbage.”

“The garbage crisis is an environmental crisis, but it’s also a corruption,” she told me. In Costa Brava, Lebanon, “I’m trying to talk about the direct correlation between our corrupt system, our corrupt government, and the destruction of our planet,” she said.

The film’s setting in the aftermath of the 2020 explosion speaks to this as well. “There still hasn’t been accountability for what happened, even though it was the result of years of political mismanagement and corruption,” Akl said of the blast in her TED Talk.

Going Green

However, Costa Brava, Lebanon isn’t interested in criticism alone. Akl, along with the film’s producer, Myriam Sassine, decided to shoot the film sustainably, taking the movie’s message to heart. The team partnered with Beirut DC, an organization dedicated to supporting Arab filmmakers, and Good Pitch, an initiative designed to build partnerships between films and civil society to create social change, to implement the green shoot.

While Good Pitch normally partners only with documentary films, Akl and Sassine convinced the initiative to take on Costa Brava, Lebanon.

“Mounia and I thought it is impossible to make a film advocating for the environment and waste reduction and shoot it in a way that would create more pollution,” Sassine said on the panel “Arab Films Go Green.” She called the 2015 garbage crisis “a slap in the face that made us more aware of the emergency of taking care of our country environmentally.”

Costa Brava, Lebanon was the first feature film in the Middle East to shoot entirely green, creating and implementing the region’s first green protocol in collaboration with Beirut DC and Greener Screen. The guide offers a plethora of green solutions to producers, with tips on everything from where to find eco-friendly soaps to a list of vendors in Lebanon who provide reusable utensils.

“Costa Brava decided to champion the planet on screen and off,” says Bassam Alassad, cofounder of Greener Screen. The film and its partners hired eco-managers and worked with catering companies to use reusable cutlery, issue reusable masks, reuse clothes, and otherwise minimize waste (Sassine joked that she shamed those who brought plastic bottles on set). In addition to abiding by the mantra of “do no harm,” the team found someone who actually lives sustainably in the Lebanese countryside, modeling the Badri family’s way of living on his. The campaign also worked with children to spread awareness of environmental issues among the next generation of Lebanese.

Shooting green, Sassine says, actually cut production costs. “You would be amazed how much a film shoot costs in terms of toilet paper and napkins,” she quipped. “We need to tell producers that [a green shoot is] easily done and that it doesn’t cost much money.”

Challenging the Patriarchy Through Film

Costa Brava, Lebanon is as much a feminist film as it is an environmental one.

While many have highlighted gender inequalities in the film industry worldwide, director Akl cites her film sets as a place of refuge. “As a woman, I’ve had to face the cracks of a patriarchal system and I’ve had to deal with a lot, but as a filmmaker, actually the film bubble was one of safety,” she said.

She has found in her film crews others who are committed to challenging injustice and reimagining what the world should look like, one story at a time. “I’ve always felt extremely safe in the environment of my film crews because [they’re] made of people that are trying to question the status quo, so they are not part of that corrupt, patriarchal system,” she explained.

Akl says this is true of the Lebanese film industry at large. “To be a filmmaker in Lebanon, you’re not doing it to be a millionaire. You’re doing it to tell stories,” she said. This tends to draw particular people, many of whom are women.

Still, according to Akl, working as a filmmaker in Lebanon as a woman is not without challenges. “I feel like sometimes there is some exoticization that happens when I’m looked at from the outside,” she says, noting that she’s often labeled as a “female Arab filmmaker.”

“I’m a filmmaker,” she said. “I’d rather stick to that. But I understand that I come from somewhere. I just don’t want it to be the only thing that defines how my film is looked at. I prefer my film being looked at as a film.”

Akl says that filmmakers who are women in Lebanon must also grapple with gendered misconceptions of their success. “We live in a system that’s patriarchal and makes you feel like you are lucky to be where you are as a woman,” she says. “Everything starts feeling like an achievement until the day you realize it shouldn’t feel like an achievement.”

Costa Brava’s characters battle these gendered assumptions too. “Each character in the movie is fighting against patriarchy,” Akl says, “even the man…who has been trapped by an idea of what a man should be.”

In giving feedback on the script, many readers told Akl that Walid, Soraya’s husband, should be more active in trying to save his family.

“Why?” Akl responded. “Why is the man supposed to save his family? Why does he have so much pressure?”

“Each character in the film is trying to break free from a box that has been defined for them,” Akl says. The father, Walid, who is both loving and at times oppressive and controlling, is paralyzed by his fear and pain.

The women in the film battle their own demons as well. For Tala (Nadia Charbel), the Badri family’s teenage daughter, Akl says that the family’s utopic mountain home actually becomes an “open-air prison,” since she doesn’t have a space to be free, forced as she is to live in a reality that her father has chosen.

Rim, the family’s youngest daughter, is trapped by the fears of her parents, inheriting her father’s anxiety, which translates to a counting compulsion.

Soraya, the lead, is, in the words of Akl, “a character who understands that maybe she sacrificed too much.” “She doesn’t want to have to make a choice between her career and her family,” Akl says. Soraya is at times resentful of the fact that she gave up a lustrous singing career to live with her family in the mountains.

Akl sees herself in all of them. “I am each one of these characters,” she says.

The Architecture of a Home

Akl did not always plan on becoming a filmmaker. Before pursuing an MFA in Directing and Screenwriting at Columbia University, she studied architecture, earning a bachelor’s degree from ALBA (Académie Libanaise des Beaux Arts) in Beirut.

“Before following my own dreams — being a filmmaker — I was a good daughter, a good girl, and I followed my father’s dreams,” she said in her TED Talk.

But for Akl, film and architecture were not necessarily mutually incongruous. “I loved architecture because my parents, who are cinephiles, were actually architects,” she said. Architecture has informed Akl’s filmmaking, encouraging her to think about the ways that spaces come to embody a sense of home.

“In the world of today, filled with political instability, climate disasters, where our spaces are constantly ravaged and threatened, how do you create a sense of home?” Akl asks.

This, I think, is the film’s central question, one very much connected to Akl’s architectural background.

Costa Brava, Lebanon offers less a saccharine portrait of hope and more a candid insight into how to go about rebuilding it in a moment of unrelenting crisis. Its making is a testament to the resilience of its cast and crew, who not only managed to find creative energy in the midst of catastrophe, but channeled that energy into a film that holds onto hope while refusing to see Lebanon through rose-colored glasses.

Even as trash begins to consume the Badri family’s home, turning their pool an ominous blood-red, the characters retain a sense of agency. As garbage closes in on them, threatening to suffocate, they refuse to be suffocated, each in their own way. Whether through the clandestine exchange of cigarettes, a stolen glance at a teenage crush, or twirling to the workmen’s music in an impromptu dance session, each member of the Badri family holds fast to their vitality in ways big and small.

As a result, Costa Brava, Lebanon is just as much about the politics of the mundane as it is about the environment. The film is at its strongest not in its overt environmental commentary, but in its forms of everyday resistance. Tala’s giddiness as she tries on her grandmother’s sparkly emerald dress, Walid’s affection for Rim’s bouts of mischief, and the soft hum of Soraya’s guitar stay with us long after the closing credits have elapsed.

“Telling the story together gave us a sense of home again,” Akl said of making the film. That togetherness is, I think, also the film’s answer on how to survive in Lebanon today. It is a film enamored with family, first and foremost.

Reporting for this article was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)