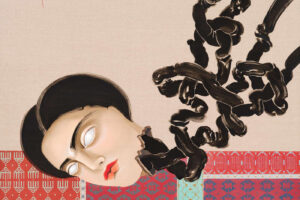

When a mother loses her child she can become inconsolable, living a desolate life, as she works for his return.

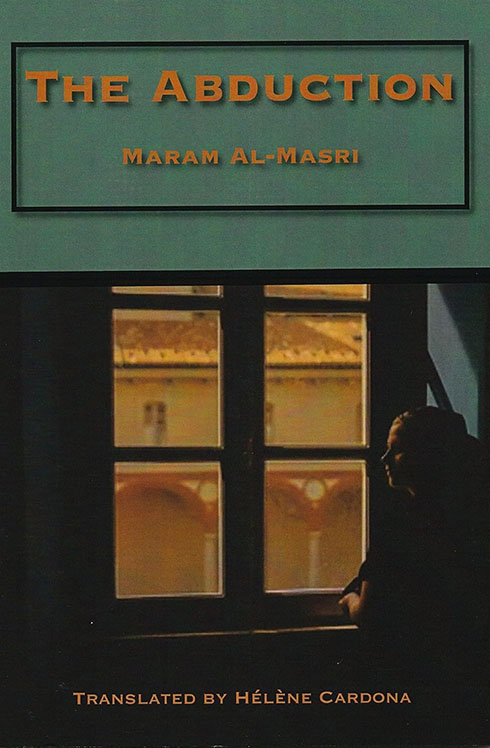

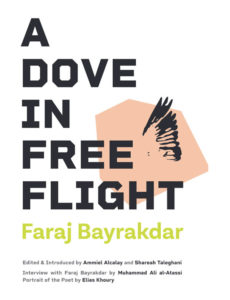

The Abduction, poems by Maram Al-Masri

Translated by Hélène Cardona

White Pine Press 2023

ISBN 9781945680618

The Abduction — Syrian-born Maram Al-Masri’s slim volume of poetry about her young son’s kidnapping by his Syrian father and her 13-year separation from him — begins like many books do, with an epigraph. The chosen quote is a well-known and perhaps well-worn maxim from Lebanese-American Mahjari poet Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet, one of the bestselling books of all time:

“Your children are not yours. They are the children of life. And life does not reside in yesterday’s house.”*

Gibran’s words ring at once true and trite, deep and hollow; they show up on greeting cards and on posters and watercolors, framed and hung on the walls of homes (including in my parents’ house, for decades now). Al-Masri does not explain, but knowing the subject of her book, I imagine the substance of the quote may not only have given her solace but also, perhaps, incited her rage. When a child is taken away from a parent, whether by kidnapping, the state, or death, the truisms of parenthood are cold comfort. By making the reader confront Gibran’s made-up wisdom before even reading her words, Al-Masri may be saying, from the get-go: “You can understand. But you can never understand.”

At their heart, Gibran’s words are about time. Life moves forward, and takes our children with it. Likewise, Al-Masri creates a sense of time in this moving and often gutting series of poems, as a way to show us the joys and loss of her motherhood. She brings us in before her son’s birth in France, with the opening poem “Nine months,” in which he grows in the womb “like a poem grows in imagination … like a loaf of bread rising/or round moon/reaching fullness.” We may not fully think through these images on first reading, but poems are forgotten, bread eaten. The moon wanes and leaves us, month after month. Potential loss hides everywhere.

In the next poem, the child is born, both in Al-Masri’s poetry (“she gives birth/to an infant in a poem”) and in life (“He cries,/I am here). For the next few poems, we follow along as Al-Masri’s son grows from infant to toddler, like we’re turning the pages of a photo album or memory book: tiny teeth, first steps, getting into drawers, sitting on his mother’s lap, going for walks, dancing. We feel the joys of early parenthood, and its hopes for the future. In “Dance, dance,” the poet tells her son, “dance, dance/my son/that you may learn to fly.” In another poem, she writes, “I talk to him/as to a friend/converse with him/as one would with grown ups.” A future in which her son leaves as an adult is always there, anticipated joyfully, not with fear.

And then, a rupture — one the poet is not expecting and yet can’t help but see herself as complicit in. She writes:

With these two hands

I prepare your suitcase

your father tells me

he’s going to take you on a short trip

to a city by the sea

…

I place you in your stroller

happy

for my little one goes for a walk by the sea

the first night passed

and to this day

my little one’s stroller has not returned

Al-Masri is in France, her son in Syria. Together, they were happy. But now …

From here, we leave behind the sense of time passing as a child grows happily older. Instead, we are stuck with Al-Masri in a repetitive loop of grief, guilt, and longing. She stops singing. She dreads sleep and dreams. She apologizes to her far-away son for not being with him. She swears she hears his breathing in his empty room. She recalls another boy, named Salim, kidnapped from his mother by his father, and realizes that her tears for him were her first tears for her son. (Back then, she could understand, but she could not understand.)

Any parent may sometimes wish for time to slow down or stop, to be able to enjoy a moment with their child forever; for Al-Masri, this futile desire comes tragically true. In “Far from my arms,” she writes to her son of the life he’s living without her while, “You’ll remain in my memory/an eighteen-month-old child/kidnapped from me.” Yet she cannot stop the passage of time in her own life, thinking, “I don’t want to grow old/so my child recognizes me/the day he comes back.”

We learn, eventually, that Al-Masri long ago lost her mother, to whom she speaks and promises “all is well” — though it’s not. Most heartbreakingly, she tells her mother:

Me, I’m divorced

Don’t panic

it’s not so bad

except if you’d been there [in Syria]

my child wouldn’t have been taken from me

In a matter of pages, 13 years pass. All through that time, the poet waits:

I wait for you when I’m awake

I wait for you when I’m asleep

I wait for you when I smile

I wait for you when I breathe

…

I wait for you

like a mother

When mother and child are finally reunited, the years that have passed are lost forever, and the son has, of course, grown. Unlike the toddler child Al-Masri lost years ago, this older child’s “mouth/is full of teeth.” The clothes and shoes his mother kept for him are too small, and she wonders if they would have recognized each other in a chance meeting. Five years after their reunion, they are still afraid to love each other. Her tears and pain continue.

Then her son immigrates to France — where she still lives — with two suitcases. In this moment, she sees him return, in a way, to his infancy. In “The world is hard, my son,” she writes,

Immigrant

you will always be in the crosshairs of suspicion

I didn’t warn you, immigrants arrive fragile as infants.

Al-Masri’s language is spare and clear, the result of a collaborative process with her translator, Hélène Cardona. In the introduction, Cardona writes, “We’ve … shared numerous phone and email conversations and met in person in Paris to work closely fine-tuning this manuscript. [Al-Masri] wrote the original in both Arabic and French and it was important to discuss the nuances.”

I have another Kahlil Gibran quote, in Arabic, framed above my desk:

الشاعر أبو اللغة وأمها

The poet is both the father and the mother of language

(translation by Adnan Haydar)

I’m not sure exactly what it means, but it points to the deep connection we make between language and parenthood — it is our parents who most often teach us our words, after all. In an interview with the Syrian arts and culture website Qisetna, Al-Masri says that for a time (presumably the years she was separated from her son), she made a decision not to use Arabic and not to write “because I was angry against my culture, against my religion. … for me, the way to show my anger was to be silent.”

This suggests the poems in The Abduction were written following her son’s return, many years after the original trauma of his abduction, to convey her experiences as a mother and to reclaim language and her poet’s role as “father and mother” of language. But the grief she shares with us has lasted two lifetimes: hers and her son’s.

Unsurprisingly, given its civil war and woes, Syria remains among the countries that do not follow international protocols when parents abduct their children across international borders. To those who think parental abduction is a mild crime or one justified by culture or religion — as well as those who believe Arab women do not have the power to speak—Al-Masri’s collection stands as a powerful rebuke.

* This is the epigraph from the book—it’s not exactly word for word what appears in the American version of The Prophet (or my parents’ watercolor), which is here.

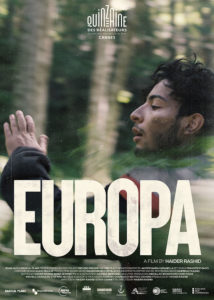

A heart-pulling account about the contortions of a mother and son relationship in a. This is the only account about the pain and angst of parenthood. Whereas my recent recall, after 52 + years of my past violent & impregnating rape by Fuad Kattan of Bethlehem. Has caused me to reevaluate my life, as well as the life of my and Fuad Kattan’s child born of his rape. Which he and his ice cold family have systematically weaponised and demonised whenever she came out to Bethlehem. For fear of the Bethlehemites being scandalised that Fuad Kattan had a bastard daughter! So she had to pay and pay she has with her emotionally & mentally degraded mental health. I am awaiting the rare possibility of Fuad Kattan’s apology for hijacking my life to raise his unwanted child born of his rape. Also, with zero financial or moral support. Come on Fadi & Karim Kattan…..Dare you to call out your rapist Papa. As Gisèle Pelicot says…..the shame has to change sides. And dare you to get to know your talented film journalist stepsister. Whom you have also greatly hurt by ostracising her, too. Ya haram!