Select Other Languages French.

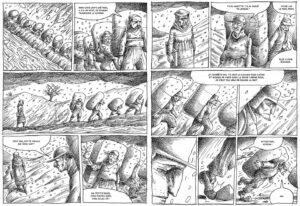

Amid the droves of protestors, TMR's contributor notes trained individuals with malevolent agendas on the streets.

I returned from Iran on January 14, after three weeks there. Consider this a social media post that I refuse to post on social media because it is toxic terrain, heavily surveilled by our own authoritarian powers, and what I write is too long anyway. I usually avoid being some self-appointed spokesperson in the Anglosphere for what happens in Iran. The ideological terrain is fraught and many in the diaspora speak from places of deep trauma. But when I first opened Facebook, I was repelled by the discussions in a language of simplified binaries, though much of it is well meaning. I write here as a person with a deep love for the country and the people, and after decades of research into its culture and history. I ask that you hold all of the pieces below together, not in opposition to each other, as so many of the narratives I’ve read do.

1.

People in Iran are extremely angry at the government for its corruption, which they consider responsible for the economic conditions that are making life increasingly unliveable for so many.

2.

Economic corruption is partly tied to decades of increasingly suffocating sanctions, which in my mind are human rights violations. This doesn’t exonerate the IRI, but they aren’t terribly unique. U.S. and European-led sanctions have impoverished and outright destroyed the middle class, the very people that they claim to want to save from the government and whose organizing abilities they undercut. This doesn’t exonerate the regime elite from squeezing the population, but again, they aren’t terribly unique in an age of global oligarchy.

3.

Angry people were out in droves protesting. Among them were also a lot of other groups, some of whom had specific kinds of training that set them apart from ordinary people protesting. I heard from people in at least half a dozen cities of various sizes. Many people I talked to in the days after January 8 and 9 told me they felt these protests were different, that there were trained people with very particular agendas on the street, trying to take over and manipulate protests (one friend was threatened for not chanting “Javid Shah,” long live the king — a reference to Reza Pahlavi). I saw someone deftly and quickly scale a 20-foot wall. This was no ordinary demonstrator. I heard a lot of other examples.

4.

Various theories that I find credible about who was mixed in with angry protestors: Israeli government agents, Israeli-backed monarchists, U.S. government-backed MEK (Mujaheddin-e Khalq, widely considered terrorists inside Iran), and U.S.- and Israeli-armed separatists. These people were attempting to guide protests to their ends and much of the violence on the protesting side came from them. Some ordinary people, watching too much Iran International (a satellite TV channel with a staunch monarchist bent that often garbles information or outright misinforms) seemed to think that Israeli and US intervention was going to save them. “This isn’t living,” they told me. They seemed under the impression that Israel and the U.S. are in the business of making things better for people around the world and of saving lives. There was little thought of what comes next. “Just get rid of this government, anything is better than this, it can’t get worse.” Oh, but it can, I told them. These governments (and significant swathes of their voters) don’t care about our lives, as their recent activities in the region show. Look at previous U.S. interventions, which have generated death, destruction, instability, and massive refugee populations. But people are so desperate, hopeless, and pushed beyond the max that they can’t hear this.

Starting on Thursday, January 8, everything went nuclear.

5.

These protests were violent in an unprecedented way. I heard this from many people who have been protesting since 2009. In many cities and towns, government offices and banks were burned, but also a lot of stores were looted, public buses burned, metro stops vandalized. Security forces or suspected security forces (some of whom were regular people) brutally attacked people in the street — hacked apart, burned, beaten badly and sometimes to death. This violence was shocking to many, in spite of their opposition to the regime, and was part of what made this feel different.

Some cities and neighborhoods were worse than others. At a hotel in a southern port city, I saw and heard tear gas, flash bang grenades, and even rapid gunfire from semi-automatic weapons. The next day I saw all the burned shops and banks, looted stores, and even found shotgun shells in the street next to “Javid Shah” scrawled on the walls. People there were shocked at the violence and one store owner who had confronted the people setting fires (he begged them not to set his store on fire because his family lived above it — instead, they just broke the windows and looted it) said, “This is a small place and we know everyone. We didn’t know these people.” A friend living in Rasht told me horrifying stories of torched buildings, gun fights, and disturbingly high death tolls. Friends who work in Tehran hospitals told me that people reported protesters and security personnel with strange accents, giving credence to the presence of foreign boots on the ground. If it sounds confusing, it is. A real mess.

6.

There is layer upon layer. The protests that began in the Tehran bazaar were fueled by economic discontent. But violence soon took over, especially in small towns no one in Tehran had heard of. In the beginning the protests appeared localized and the government seemed to show restraint. Yet Western media did what it always does, blow everything up into an incipient revolution, with no context. For instance, government corruption is always mentioned, but conveniently amputated from the context of decades of ever more crippling economic sanctions, which have made it so that the trade that provides many goods of daily life flows through a giant black market. As sanctions keep tightening, elites scramble for the ever more difficult to get U.S. dollar, printing more and more domestic money that becomes increasingly worthless, pinching ordinary people in the process. To complicate matters, not all the mafias that control the flow of goods are under government control. This doesn’t exonerate the regime from the responsibility it has for the well-being of its citizens, but context as always remains distorted or nonexistent.

7.

Starting on Thursday, January 8, everything went nuclear. I asked more than one person whether I had just not been paying attention or things actually had gone completely next level, and everyone confirmed the latter. After Thursday night, the government decided to crack down hard. The 12-day war with Israel seemed not over, but merely paused and continued by other means. The regime is like a wounded animal that feels cornered by the obvious foreign elements lacing these protests, which escalated in the streets on Thursday and was met with gloves off on Friday. It was like war in some places. Thousands were gunned down or arrested — many young people in despair over the future, bludgeoned between the authoritarian state’s fist, their own rage, and the machinations of various outside groups. After Friday night, which was truly horrible on every level, things quieted down. By Saturday, I was back in Tehran. Though I heard from people that in virtually all neighborhoods there were chants and localized protests, most people closed up shop to make it home by dark. This was partly out of fear and shock at the violent escalation of recent days. Sunday, there were some chants of “Death to the Dictator” in my central Tehran neighborhood. After that, nothing. As of Tuesday night, unlike international news reports of massive security presence in public areas, I didn’t see more than several clusters of police here and there.

8.

In the days that followed, until I left Iran on Wednesday, the city was subdued. People kept trying to live their lives and attend to their day-to-day business. Nights were more deserted, though people began to come back into the streets. I went out Monday and Tuesday in the early evening. The lack of internet made business and everyday life difficult, as we all struggled to function like it was 1999. It was also strangely calming, in that it helped us be present with ourselves and each other. The intranet was restored by Saturday for things like banking and car service. By Sunday evening the government stopped cutting the phone lines at night. We couldn’t text each other, but we could call. And we did. Reaching out, talking, listening. For me, that was amazing and something I miss in the U.S., where when something hard happens it’s not okay to talk about it, or doing so actually makes people uncomfortable. Or there is just no time/energy because of never-ending work that is life here.

By Monday, I had hit a wall of hurt, literally.

9.

By Tuesday, some people (again, those watching Iran International), seemed to think that Donald Trump or Reza Pahlavi was going to swoop in and bloodlessly save them from the regime. But others, even those in northern Tehran whom you would not think would say this, were cursing the former crown prince. “How dare he call for protests and get all those young people killed. What is his plan? He has no plan.” I think all the magical thinking about Pahlavi and Israeli/U.S. intervention is a sign of just how fed up with the regime wide swaths of people are, desperate for something better than the current conditions of economic collapse.

10.

Others, the more educated and/or thoughtful, were fearful of what is to happen. Of civil war, of a massive destabilization that would bode ill for the basic security of society. Literally no one I talked to defended the regime. But they feared, in the current domestic context of a lack of viable opposition and the international context of nefarious foreign forces, that there was little hope of a peaceful transition to a better government. I share this fear. Things could get much worse and many are just too knee-jerk against the regime to see the real dangers and limitations of this moment. There doesn’t seem to be any kind of viable plan, either on the part of any opposition or on the part of any short-sighted government.

It’s hard to be hopeful about anything, but the real beauty of Iranian society when things go bad is the way people come together. By Monday, I had hit a wall of hurt, literally. Muscles along my back and sides kept cramping painfully. It was sunny so I thought it would help to take a walk to a nearby park. I started crying halfway there. At some point in the park, another painful cramp hit and I was bent over a bench trying to breathe through it. I sat and tried to gather myself, breathing slowly as several men walked by rhythmically passing beads along their tasbih strands. Just watching them soothed me enough to call a dear friend.

I didn’t even try to pretend, “I’m not doing very well.” She talked me through it, we made plans to meet up in a couple of hours where she worked. We gathered with her colleagues, had tea, talked with them, before going off on our own for dinner and a stroll through central Tehran. These interactions were ni’mat, a grace, a blessing. It was really difficult for me to leave those so dear to me behind a wall of silence. We don’t know what is going to happen. But I learned from being there with friends and family (and the kind woman who comforted me as I broke down on the flight out of Iran) that we just have to continue to try to live as best we can.

That’s all I’ve got for now.