Select Other Languages French.

Cutting Through Rocks turns one Iranian woman’s daily battles into a portrait of determined rebellion.

It begins with a clang. A stubborn old gate refuses to work properly as a middle-aged woman leans into the metal, fighting it over and over until it gives in to her will. Sara Shahverdi isn’t just repairing an entryway — it’s a perfect entrance for her. This is the revealing opening sequence for Cutting Through Rocks, a feature documentary that understands how metaphor can speak louder than dialogue. This is just the first of numerous outdated obstacles she will face: rigid, rusted, and unyielding.

Sara lives in a small Iranian village where women are expected in their early teens to quit school and marry, surrender property, and disappear into domesticity. But she is an anomaly. She is educated, divorced, and proudly independent. Clad in untraditional garb, she rides a motorcycle, her face shielded from the harsh wind and judgment, her entire presence a rebellious refusal to play by the patriarchal rules. She is a woman whose very normalcy is treated as a threat.

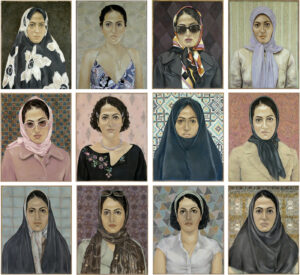

Premiering this year at Sundance, where it won the World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Documentary, Cutting Through Rocks follows years of Iranian women’s protest for their emancipation from the patriarchy of the mullahs, who followed in Ayatollah Khomeini’s footsteps after the 1979 revolution in Iran. Women fought these battles during the 2009 Green Movement and were beaten back by the “Morality Police” time and again, but in 2022, after the suspicious death of Mahsa Amini after her arrest by the authorities, women and the men who loved them came out again in force. More protesters would die, but this time, the mullahs loosened their grip on Iranian society, such that today, one finds more and more uncovered women out in the streets, demonstrating their independence from the hijab and the chador. These social changes have also taken hold in some smaller, rural areas of the country.

This is the context in which Cutting Through Rocks was filmed. And it’s clear from the start that Sara Shahverdi is a woman who doesn’t shy away from a fight. Her first comes when her brothers force her sisters to sign away their inheritance to them. Sara confronts them, demanding the document. When they eventually acquiesce and give it to her, she rips it up in their faces. It’s the first clear signal that she’s built from different steel — and that everyone around her knows it.

From there, the film pulses like a political thriller. Sara decides to run for the town council — the first woman to do so — and, garnering the female and youth vote, wins with the highest vote count. That distinction entitles her to the official town seal, a literal stamp of power that her male colleagues try to withhold. She forces the issue and gets it, nobody willing to get swallowed up in the maelstrom of her mission — for now, at least.

She makes good on her campaign promise to bring natural gas to the town, but not without enacting a bold rule: any man who wants gas service must legally sign over half his property to his wife. What begins as infrastructure becomes a one-woman revolution. But she is just getting started. In another scene, she strides onto a dusty vacant lot and explains her vision to a confused cadre of male engineers and construction workers: a circular park, unlike the traditional square parks built by her male predecessors. The metaphor of Sara being a round peg in a square town is almost too perfect to be real.

But as Sara continues her one-woman revolution, the unwieldy weight of tradition starts to slow her effort, the way the boulder slowed Sisyphus’ climb. She begins teaching young girls in town to ride motorcycles, but male relatives intercede and stop their convoy. When she refuses to rubber stamp corruption, a male council member demands she return the town stamp. Eventually, the mounting pressure builds into something more ominous: a regional court summons her. What happens next is the film’s most haunting sequence.

The court proceedings are shot clandestinely. Faces are never shown — only hands, shoes, shadows. The camera trembles in close quarters, as though filming something forbidden. It becomes a chilling metaphor for Iran’s subjugation — a faceless system that crushes individuality. And then we hear a male judge render his shocking judgment. Simply for behaving as a free woman, he demands Sara undergo a humiliating test.

Behind this extraordinary film are co-directors Mohammadreza Eyni (who also serves as cinematographer) and Sara Khaki, a collaboration that shapes a work both intimate and sweeping. Eyni and Khaki formed their own production company, Gandom, which, per the company mission statement, focuses “on creating films that resonate across cultures and connect audiences worldwide through visually compelling narratives.” Khaki works as a director, producer, and editor, while Eyni is the director of photography, in addition to his directing and producing roles. Born in Iran, Khaki obtained an MFA in the U.S. in social documentary filmmaking, while Eyni graduated with an MFA in cinema from Tehran University of Fine Arts.

For a documentary, the visual language is extraordinary. The cinematography is not just beautiful, it is purposeful. The sun on the horizon glints off the silhouette of Sara on her motorcycle, unclear whether it’s setting or rising. A bonfire lights her face against a pitch-black night, a visual echo of her own efforts in the darkness of convention. And throughout the film, we see closeups of a young woman weaving a tapestry on a loom; the directors return to that image again and again, thread by thread, until a striking portrait of female defiance is revealed.

As a result, Cutting Through Rocks looks more like a carefully crafted feature than a documentary. Each scene tightens the coil; each encounter is an ominous step toward a climax. One must remind oneself that it’s a documentary, because it’s hard to believe all of it — both the images and actions — aren’t scripted.

And at the center is Sara, determined and defiant. But this isn’t fiction, and reality, she soon learns, does have its limits. She continues to push, until the town pushes back harder. She inspires, until the system smothers. She wins battles, but the war remains impossibly large. Near the end, Sara begins to sense the hard truth: the ingrained patriarchy will bend only so much in a short time. The filmmakers don’t offer triumph or defeat — they offer something far more truthful: the realization that resistance is not a single victory, but a long, grueling journey.

Cutting Through Rocks leaves you breathless not because of its outrage but because of its clarity. It shows how change happens, through persistence, through friction, through the refusal to be silent even when the world demands it. Sara’s story, at least for now, isn’t so much about conquering patriarchy, but confronting and unsettling it.

Sara doesn’t shatter the system. But she cracks it — and that’s enough to offer hope for the future, anywhere people are waiting for their own Sara.