"Sayed" and "Sultana" are an unlikely pair: one, a single man accustomed to his solitude, the other, an older woman with a tragic past in Syria. And yet, a healing friendship develops over Turkish coffee and seemingly miraculous meals.

September in Lebanon carries the melancholy that follows a mass exodus. The beaches close their shacks, and the village squares, filled with diasporans drunk on arak and nostalgia, fall silent. Most of my friends couldn’t handle this stark shift from party to monastery, so they’d travel elsewhere, but I appreciated the quiet time it offered. This was the first Sunday I had to myself in months, and I spent it alternating between reading on the balcony and watching TikTok videos on the living room couch. I was about to fall asleep when I heard a loud, hurried knock on my door. I opened it and found a woman with thin, tattooed eyebrows and large, brown eyes the color of manuka honey.

“Marhaba,” she said, “I’m Jameeleh.”

“Ahlein, how can I help you?” I asked.

“Well, I just want to clarify that I am not begging,” she said firmly.

“I didn’t think that you were,” I replied. A smile crept onto my face because I remembered my late father and how upset he would get when volunteers for Jehovah’s Witness knocked on our door on Sundays.

“Can I come in?” she asked.

“Sure,” I replied. “Excuse the state of the house; I’ve been away for most of the summer.”

I walked her to the balcony and told her I’d come back with a pot of Turkish coffee for us to share. “No cardamom. It raises your blood pressure,” she said.

In the kitchen, I wondered what she might want from me. Was it money? Or was she here on behalf of someone interested in buying the apartment, as is often the case?

I brought back coffee and some almond cookies, and we sat on the edge of the balcony facing the Hypco gas station. She thanked me and said, “You must have been a tiny boy when this gas station was a park. It had the tallest pine trees I’ve ever seen in Beirut.”

“Yes, and jacaranda trees that had lilac blooms in the spring. Now we have a loud gas station,” I said.

“I know the owner. He’s the worst of the worst. A thug. These poor men wash cars for him day and night, dreaming of getting on his good side so they can secure a residence permit,” she said.

“A thug indeed. The mayor protects him,” I said.

She took a small sip of the coffee and complimented it.

“I learned the art of foaming from my grandma,” I said.

“Hajjeh Anbara, may she rest in peace. She was a man of a woman,” she said.

“She was,” I said. “How do you know her?”

“She stood by me when my own family didn’t,” she said, offering me a cigarette. “Having Turkish coffee without a cigara is like marriage without love.”

“Yalla,” I said, taking one from her.

“Sayed, I won’t take up much of your time,” she said. “I need a job, so I’ve been knocking on doors to see who might want a cleaner or a cook. Anwar, the natour, told me you live alone. I thought I’d offer my services.”

“He’s known for having a big mouth,” I said.

“And a big appetite for you know what,” she said. “He’s living with that poor woman with eight kids, in a room smaller than a scorpion’s pussy.”

I wasn’t expecting that kind of comment from her, and I nearly choked on my coffee.

“Allah Y’eeno, we all have our burdens to carry,” she added.

“Jameeleh, I’d love to help, and I can give you some money, but right now I don’t need someone to take care of the house,” I said.

“Habibi, listen. You live alone. A busy man like you — what with all these books and notebooks on the table — probably doesn’t have time to cook. These Toters* motors delivery your generation orders for breakfast, lunch, and dinner will only give you acid reflux and high cholesterol,” she said, crossing her right leg over her left. “My cooking is so scrumptious; you will devour your fingers while eating it. And my son is into fitness, so I can also make you diet meals,” she said.

Impressed by her enthusiasm, I was about to agree, but I paused for a moment. I grew up in a busy house where people from all walks of life came and went at any time of day. We weren’t allowed to turn away guests, and if my grandmother were too tired to entertain, she would close the curtains on her balcony to signal to visitors outside that it wasn’t a good day for a chat. When I moved into my house, I appreciated the solitude that came with it; I no longer shared space with half the neighborhood.

Jameeleh noticed I was hesitant, so she stood up and said, “How about we do a taste test?”

“I only have potatoes and a few other vegetables in the fridge,” I said, embarrassed.

“Perfect. You stay here and enjoy your Sunday afternoon, while I make us a light dinner,” she said, walking toward the kitchen with the confidence of someone familiar with the place.

While she was in the kitchen, I called my mother to tell her what had happened. She was also abroad, visiting my sister in Qatar. “Eh, haram, help her,” she said. “I heard her daughter kicked her out because she ate too much and didn’t pay enough for groceries. Imagine what Lebanon has come to. Your kids throw you out and demand fresh dollars for your share of chicken and onions.” Hearing this, my stomach squirmed with sadness.

About an hour later, a sweet aroma of oil infused with seven spices filled the house. Jameeleh returned with a bowl of tabbouleh bursting with shades of red and green. She wrapped a handful of crispy, golden French fries in pita bread, sprinkled something from her pocket, and finished it with ketchup and paprika. After the first bite, my eyes widened like a child’s, and I looked at her and said, “Can you come every day except Monday and Saturday?”

“Inshallah,” Jameleeh said.

In a month, Jameeleh turned my house into a farm. There were molokhia leaves drying on the window overlooking Abdallah Al Machnouk Street and jars of tomato sauce filling the balcony in preparation for winter. The dining room table became a lab for sorting pebbles from lentils and checking whether salt was coarse or fine. In the kitchen, there was always something simmering. Today, it was stuffed zucchini slow-cooking in a broth of tomatoes, lemon, Seven Spice, and Jameeleh’s secret ingredient, which she kept in a small plastic wrap in her pocket and often added a teaspoon to all her dishes.

I walked into the kitchen and tasted a spoonful of the broth, which only made me dream about what was to come at lunch. “Wallah, I don’t know how your food is this good. You could unite all of Lebanon with the smell of your koussa,” I told her.

“Wallah, ya Sayed Malek, the only thing that can unite Lebanon is money,” she said. “Your neighborhood has Sunnis, Christians, Shia, and Druze. They’re not fighting each other. Why? Because they can live a stable life,” she said, moving to the kitchen balcony, which she had transformed into a spice cavern with racks of oregano, jars of dried lime, and onions knotted into dangling sacks. She stood in the middle staring at her collection with the pride of a maker.

“Well, it’s not always this stable. Since May 7, this neighborhood has lived in fear of conflict returning. I remember hiding in the bathroom while my grandmother fought off armed men with her rolling pin,” I said.

“She was a tough woman,” she joked. “That was in the past, inshallah.”

“Inshallah,” I said. “But for the millionth time, stop calling me Sayed.”

“You’ve been nothing but a gentleman to me, and the men in my family are always called a Sayed,” she said.

“Fine, then I’ll call you Sultana,” I said.

“Sayed and Sultana, we sound like a Turkish soap opera,” she said with a wild laugh.

At two p.m., we sat down together for lunch. Jameeleh had spread the table with various vegetables, from radishes to arugula leaves and lettuce. She never mixed them into a salad; instead, she nibbled them separately like a rabbit. “Fresh food keeps our spirit light,” she would say.

I placed three pieces of koussa on my plate, and Jameeleh insisted I add more. “This is all healthy. I don’t use lard or vegetable oil in my cooking. Be careful of those ingredients. A cheap shortcut, and they give one a big ass. I’ve seen photos of your mom. Ya’ne, all I’ll say is, be careful,” she said.

“Sahten,” I replied. Biting comments like that never seem to hurt from Jameeleh because I know they come from a place of love.

Over lunch, Jameeleh was talkative, discussing everything from politics to the fake news on WhatsApp. Today, she was quieter, and her voice, hardened by years of smoking, sounded softer.

“Is everything all right?” I asked.

“It’s nothing,” she said. Jameeleh rarely shared details about her private life with me. All I knew was that she had lived in Tripoli for ten years, and after her recent eviction, she rented a house with her son Omar in Kola. Her daughter, Feryal, was now dead to her.

“Don’t be shy, Jameeleh,” I said. “I always talk to you about my problems. Remember the issue with my students a few weeks ago?”

“Those students, you need to smash their phones,” she said before quieting again.

She tore up a bunch of rocket leaves onto her plate. “It needs more salt,” she said.

“No, it’s perfect as it is,” I said.

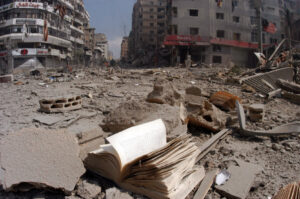

She sighed and said, “I don’t like talking about depressing topics, but with the news coming out of Syria, you can’t help it. I’ve been watching the videos of the freed prisoners for days, and those digging up their loved ones, dead or alive, from Sednaya. I’ve been glued to the phone and TV, wondering if my lover will return too,” she said.

This was the first time I heard about Jameeleh’s husband. I assumed she was a widow because she carried herself masculinely, as matriarchs often do.

“Is this about your husband?” I asked.

“Yes, Abu Omar,” she said softly. She lit a cigarette, offered me one, and asked, “Do you feel a certain way when someone is gone for so long and suddenly you get this strange reminder that they were once a part of your life? A big part of it.”

“Yes,” I said. “I don’t often think about my father, but sometimes I’ll suddenly remember him. The other day, I was flipping through my phone’s photo gallery and saw a video of him dancing on the balcony. I cried, then I laughed because that kind of happiness he lived isn’t common anymore.”

“Allah Yerhamo,” she said, shifting her eyes to his small portrait in the living room. “He was a handsome man, Metlak.”

She started packing the remaining food into Tupperware and told me the story of her husband. “Abu Omar vanished during the Civil War. He was from Syria and part of a student movement campaigning for a free, democratic Syrian state. Just saying it out loud sounds absurd, but he was an idealist, unlike the men of today, who care about their wallets and stomachs.”

She moved to the TV room next to the table and turned on Al Jazeera, where the anchor spoke from a square in Aleppo as people celebrated in the background. “We met at Ajram, the beach in Ein Al Mreyseh. I have a thing for tall guys; he was tall everywhere,” she said with a wink. “I don’t often cry, but this time I cried tears of joy and grief. He dreamed of this moment his whole life, and it’s unfair that he’s not here to witness it.”

“It’s only been a week; he could be one of the returnees. You saw that man who walked into his village in the North after twenty years away. You never know,” I said, trying to reassure her.

“I called my friends from ACT for the Disappeared. I used to camp with them downtown for years, rain or shine. They haven’t heard anything yet. Whatever is meant to be will take its course,” she said. “I spent decades thinking of him. Is he being tortured? Is he being starved? Is he sharing the bathroom? He had crippling OCD. But one day, for the sake of Omar, I had to stop. He was already fatherless, and if I were still trapped in the past, he would be motherless. And now, his father is plunged back into my life years after losing him,” she said.

“You’re strong, Jameeleh, I know you are. Omar will understand the importance of this moment,” I said.

“Last night, I had a beautiful dream. That’s why I’m a bit shaken. I dreamt he walked from Syria to our old house in Aisha Bakar, knocking on my door in the morning, in time for his favorite breakfast tray — za’atar, labneh, and orange blossom jam. I recognized him because his skin was as smooth as marble and his hair was blacker than the olives on his tray. We had breakfast and discussed his plans to revive his old center,” she said.

“Maybe he’s sending you a message. I’ll pray for him tonight,” I said.

“Habibi, please do,” she said. “Look at us being so sad over lunch. We should be happy there’s some good news in our wretched region for once. Let’s not prolong this Turkish soap opera.”

“Yalla, I’ll make us some coffee. This time, with sugar because we both need it,” I said.

“Yes, two teaspoons of sugar. But no cardamom,” Jameeleh said.

“Inshallah,” I said.

* Toters is the main delivery app in Lebanon.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)