Select Other Languages French.

Lebanon's ruling class have long espoused a philosophy of governance that can be summed up as "business as usual." But what of its citizens?

“Injustice Upon Injustice: Lebanon’s Failure to Investigate Israeli War Crimes.” This is the title of the latest report by Badil, a Lebanese research institute that offers an alternative approach to policy advocacy.

To my shame, upon reading it, I caught myself chuckling — hard. In all fairness to me, the sniggers were more at the expense of the Lebanese state than this team of researchers and policy advocates. But I cannot deny that I found their earnestness a bizarre suspension of disbelief. To my shame, again.

Demand anything remotely serious from the Lebanese ruling class, and you risk derision. Of all their achievements, I have little doubt they would agree that this by far is the finest. To reduce a people to a temperament of unexpectancy so deeply ingrained that it makes us reflexive subscribers to our own impotence is not a unique Lebanese skill, but mine actually is a subtle twist on the obvious. We Lebanese are more than mere subscribers to the state’s inconsequence, we are active partisans of it. And therefore of our own.

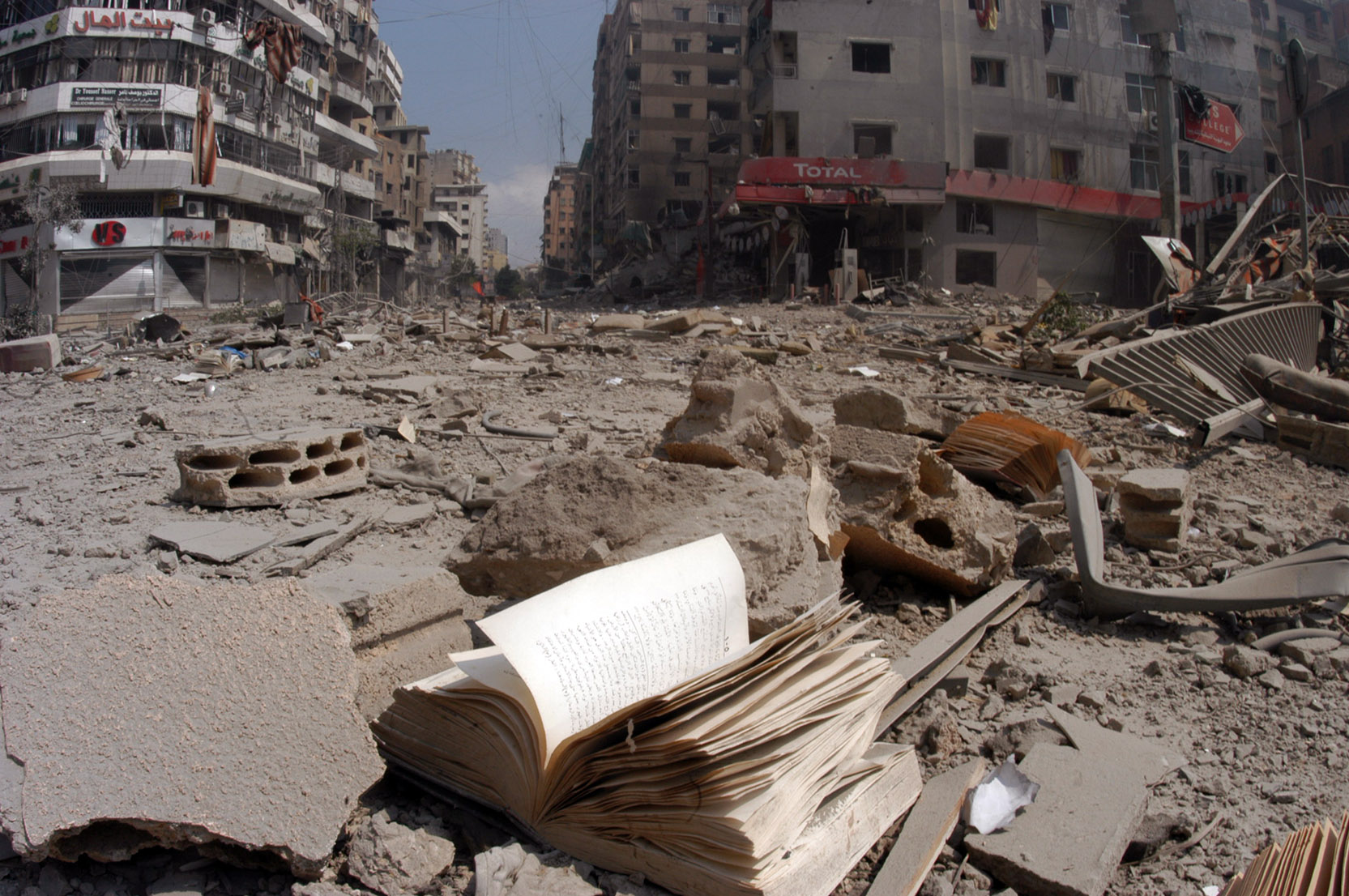

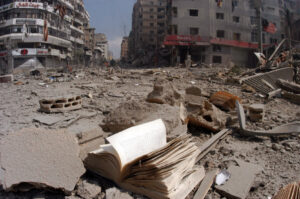

A sham of a state begets a sham of a people! It works just as well the other way around. We both, Lebanon and Lebanese, are victim and culprit all in on this crime. Because of it, we are complicit in countless other injustices, including passivity about the worst of them: Israeli war crimes. That’s the predicament of the powerless, we tell ourselves. We make do with its hardships, mistaking ours for resilience against adversity, when it is nothing more than forgiveness towards our saddest failings.

Our elites, ready to take every liberty, espoused long ago a philosophy of governance best described as: business as usual. After civil strife, business as usual. On the heels of a financial and economic meltdown, business as usual. Right before, in the middle of, and in the aftermath of crippling wars, the same. So it is, in the wake of a simultaneous overrun of all these calamities.

Even as we all keenly sense a scheme being hatched somewhere else on our behalf and at our expense, theirs is also business as usual. I have in mind the menace of even more diminished prospects for this fracturing country as it is cajoled into a peace treaty with Israel that effectively gives it the run of our south, our seas, and skies. And if not, all the better for the Israelis, as we grow ever more embattled, splintered, small, and ignored on a map that barely registers us.

In such dire circumstances, the peers of the realm haggle over ministries, positions, and contracts; freely indulge in sectarian bickering as they, on and off camera, agree between themselves their share of spoils and influence; and, with extraordinary alacrity, forge an airtight consensus to fend off even the most superficial corrections pivotal for the survival of the very system they depend on for wealth and relevance.

Whatever the period, the actors, and the reforms compelled on paper, this has remained their fundamental mode of behavior. Remarkably, even as the profile of leaders in this tight but elastic network of sectarian and business interests has changed across generations and crises, the oligarchy itself stayed true to its excesses and addictions. Inevitably, the effect of this delinquent devotion to the order of things has ensured exactly the opposite for all of us. With the passage of time and the habitual recurrence of crises — each round more absurd and tragic than the last — we have become ever more ridiculous as we proclaim our love for a Lebanon that we know is pure fabrication.

In this world of make-believe, we the people live and move in a constellation of bubbles and geographies. It is a preposterous life, but we readily bow to its logic. I suspect most of us understand now that this will likely remain our mode of existence. And precedent has taught us that the future will only sharpen its degradation.

Of course, the more privileged we are, the better our coping mechanisms; the worse off, the more invisible we become, dropping completely out of sight to the bottom of the rung and into a universe of heartbreaking statistics. Ironically, without these numbers, many of us would be naïve to the tangible repercussions of our supposed stolidness.

I do not know who first crowned resilience as our most winning trait: we Lebanese or admiring outsiders. Resilience, I hasten to add, not as sumūd in resistance to an iniquitous status quo, but as pragmatism in accepting its inequities. Perhaps it’s the feisty life that always seems to stubbornly tick in us as we collapse into rival enclaves and inchoate city-states. I’ve written it before: Lebanon is a story of individual genius and collective failure. But if we insist on celebrating our discrete endeavors in this colossal communal undoing, then let it be in recognition of the islander in us. Because that’s truly who we are: inhabitants of tiny lives on tiny islands. We’ve been in limbo for so long, we’ve carved a nice little space in it, set up house, and resolved to call it home.

On Another Note

I return this week to Robert Harrison’s Entitled Opinions, to share his discussion with Grant Dowling on the philosophy of inaction. Many of my Lebanese compatriots may find it very enlightening.

Vita activa and vita contemplativa! You may have the idea by now that the conversation would be entirely too demanding for a weekend of leisure, but you would be mistaken.

Have a listen!

Amal Ghandour’s biweekly column, “This Arab Life,” appears in The Markaz Review every second Friday, as well as in her Substack, and is syndicated in Arabic in Al Quds Al Arabi.

Opinions published in The Markaz Review reflect the perspective of their authors and do not necessarily represent TMR.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)