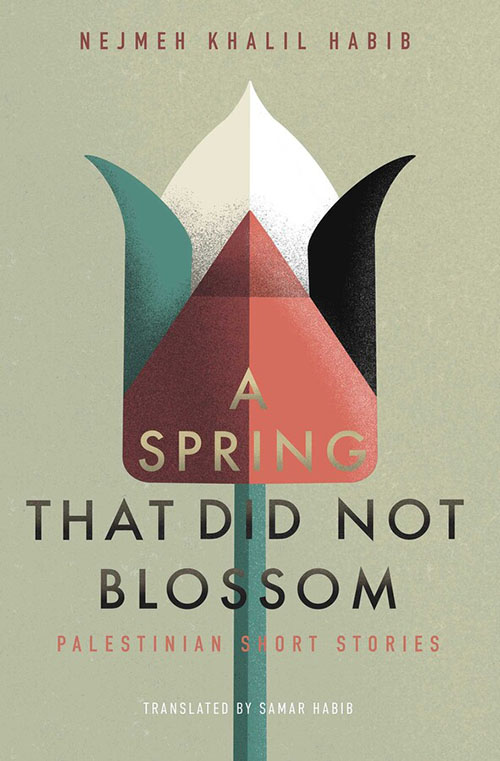

Set among Palestinian refugee communities in Lebanon during the 1970s and early 1980s, Nejmeh Khalil Habib’s stories of love, loss, and annihilation anticipate the horrors of Gaza today.

A Spring That Did Not Blossom: Palestinian Short Stories, by Nejmeh Khalil Habib

Translated from Arabic by Samar Habib

Interlink Books 2025

ISBN 9781623716639

Known throughout the Arab world as a poet who has cultivated a unique style of prose poetry, Nejmeh Khalil Habib is also a literary critic who has published studies of Ghassan Kanafani, Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, and other key figures in Palestinian literature. Presently a lecturer at the University of Sydney in Australia, her writings are entirely in Arabic. In addition, she has penned two works of fiction: And the Children Suffer (2001), and A Spring that Did Not Blossom, which first appeared in Arabic in 2003 and has now been rendered into English by Samar Habib and published by Interlink. In the six interlinked fictions that comprise the book, we become immersed in the inner lives of Palestinians living in Beirut as they navigate their relationships, their lives, and their frustrations, and are ultimately destroyed by Israeli bombs.

Although framed as a short story collection by the English-language publisher, the book could just as easily be classified as a non-linear novel, and it is indeed described as such in Arabic media. (I follow the conventions of the English and refer to each separate chapter as a “story.”) What makes A Spring that Did Not Blossom different from most novels is that there is no single protagonist. The stories move rapidly in and out of the minds of a wide cast of characters, some of whom are only loosely connected to each other, and others who don’t know each other at all. In this way, we are introduced to the full spectrum of Palestinian society residing in Lebanon. The characters live in Palestinian refugee camps such as Bourj el-Barajneh, Ain al-Hilweh, and Shatila, the latter of which will be forever associated with the massacre that took place there in September 1982, the subject of Jean Genet’s famous essay. They find ways of leaving the camps and relocate to apartment buildings in West Beirut. Some characters fight for the Resistance while others do their best to lead a quiet life.

The intimate tone of Habib’s narratives sets her stories apart from much fiction where the action unfolds against the backdrop of war. Snippets from newspaper headlines and news briefings are incorporated into her prose, generating tension between the two discourses, the personal and the mediatized. Violence runs deep through the core of Habib’s stories, but it does so with intimacy and even delicacy, less as a grand event or an ideology worth fighting for than as unobtrusive suffering that silences, maims, and kills.

Ellipses govern this assembly of excerpts, gathered together like the shrapnel of a destroyed building…

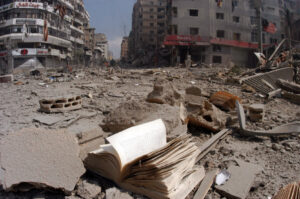

Like much of her prose, Habib’s title, A Spring that Did Not Blossom, is a double entendre. It refers both to the term as translated, that is, the season, as well as to Rabih, the young boy around whom the lives of many of the characters are centered. Miriam and Awad get married in their forties in the hopes of conceiving a child. They succeed, and Miriam gives birth to her only son, Rabih. Then, at the end of the first story, everyone dies in an instant, an Israeli airstrike erasing their building from the face of the earth. The remaining stories narrate life under the 1982 Israeli siege of Beirut from the vantage point of the survivors. Sometimes they look back in time, to the moments shared with those who were killed when the apartment complex was bombed. Even when they are not enduring a campaign of incessant bombs, the reign of terror produced by the war permeates the atmosphere.

In “Miriam,” the story that opens the collection, Palestinian refugee Abu Rabih (father to Rabih) returns to wartime Beirut to reunite with his family after a stint spent working in an unnamed Gulf state in order to provide for his family. The Israeli invasion looms on the horizon, the streets already tumultuous with the violence of the Lebanese civil war. As Abu Rabih approaches the building where his family lives, he comforts himself with the reason why he believes they will remain safe: “the Israelis care about public opinion; it’s impossible that they’d bomb this building.” So thought many in 1982 — and so imagined many before October 2023. Yet the actual Akkar building (Banayat Acre in the English text) where the fictional Abu Rabih’s family lived was in fact completely destroyed by Israel in 1982, in what is now known as the Akkar Building Massacre. The atrocity was eulogized by Mahmoud Darwish in his long prose poem “Memory for Forgetfulness” (1986), and by Jordanian writer Amjad Nasser in his published diary of the siege of 1982. It was also featured in Under the Rubble (1983), a documentary by Jean Khalil Chamoun and Mai Masri. Now we have it rendered unforgettably, in all its horrific detail and from the vantage point of its victims, in fiction.

Just as Abu Rabih comforted himself by imagining such atrocities were impossible, so have many observers of Israel’s genocide in Gaza comforted themselves since. Then and now, red line after red line posited by politicians, media commentators, even common laws of warfare have been violated so quickly it was as if they never existed. In this respect, Habib’s text is disturbingly relevant to our present moment. So too is her description of the psychological terror that Israel inflicts on the civilian population. “An unprecedented kind of war was being waged on Beirut and its people,” the narrator recalls. In this “psychological war,” pamphlets are “dropped from airplanes, drifting onto balconies and sidewalks, waking people from their naps.” In a gentler version of the nightmare currently transpiring in Gaza, the pamphlets “advised the people of Beirut to leave and promised them no harm if they were to take certain roads.” They “pretended to show empathy but concealed a significant threat.” In the dropping of leaflets across a territory targeted for annihilation, we see some of the same tactics used in the current genocide, if in milder form.

Translator Samar Habib (no relation) compares Nejmeh Khalil Habib’s terse prose style to that of Kanafani. There is truth in that characterization, further substantiated by the direct references to Kanafani’s short story “Men in the Sun” (1962) in the text as well by the fact that Nejmeh Khalil Habib published a book on Kanafani’s fiction. I was also reminded of the prose of Toni Morrison: Both writers render violence in an intimate style that is shocking in its delicacy yet brutal in its documentation of atrocity. They capture violence as it is experienced in the bodies of women, and by their bewildered children.

Like Morrison, Habib draws on the world of documentary fact, especially journalism. For Morrison, a newspaper clipping she encountered about Margaret Garner, an enslaved woman in the American South who committed infanticide in order to prevent her child from being sold into slavery, led to her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Beloved (1987). Morrison reworked that barest outline of story into a rich, fully textured novel that narrated the steps Garner took to prevent her daughter from becoming enslaved.

In similar spirit, Habib fills in the gaps left untouched by journalistic narrative. She introduces fictional characters alongside actual ones. Yasser Arafat (Abu Ammar) makes many appearances indirectly throughout the text. His whereabouts are indeed the reason why the entire residential apartment building where Abu Rabih’s family is sheltering in the hopes of safety was blown up by Israel forces, deploying a new American-produced weapon: the vacuum bomb, designed for use in the jungles of Vietnam. Knowing that he might be targeted, Arafat went underground, so to speak. He was sleeping in the backseat of a car when the building the Israelis mistakenly identified as his hiding place was bombed to the ground, killing over two hundred and fifty residents.

There are also cameos from the literary world, including the poet Khalil al-Hawi, who is the subject of the second “story.” The trajectory of al-Hawi’s life coincides with Israel’s war on Lebanon. When he heard that Israel had invaded Beirut in 1982, al-Hawi shot himself in his apartment near the American University of Beirut, succumbing to his wounds immediately. Although he never appears in person, Kanafani is named several times by the characters as a journalist and writer. There is also a character named Darwish, who may or may not be the famous poet Mahmoud Darwish, but the coincidence of names resonates like a metatextual allusion.

The tension between fictional and journalistic ways of representing war is powerfully exposed in the concluding pages of “Miriam,” in which the destruction wrought by the Israeli war machine results in the death of nearly every character we have been introduced to thus far. How to narrate such horror? It cannot be done in the first person, because the consciousness of every potential narrator in the story is about to be annihilated. So Habib breaks with her typically intimate style and shifts to third person. The contrast between this omniscient style and the intimacy of the rest of her narrative makes the narrator’s deadpan monotone all the more striking. “There was no building there,” we read after the edifice has been leveled to the ground. “It was as if the building had been an empty cardboard box whose sides had been compacted against each other when squashed under two strong feet.”

The narrator’s indifferent monotone may seem inappropriate for describing the deaths of the characters in whose lives we have been immersed since the beginning of the story, but what better way is there to expose the atrocity of what has just occurred? The difficulty of finding appropriate language is one that many of us are currently facing as we look upon the genocide in Gaza. We are all grappling with the incapacity of language to capture the atrocity, let alone to stop it. Words do not suffice. And yet we continue to write, bearing testimony to the atrocities, so that the stories of martyrs will be remembered for generations to come.

In its concluding paragraph, “Miriam” splices together journalistic reports that understate the casualties from the bombing. Ellipses govern this assembly of excerpts, gathered together like the shrapnel of a destroyed building, signifying, without fully representing, the horror of what has just happened. The final sentence names the characters who were introduced at the beginning of the story, now all dead: “A relative was able to identify the family of four by recognizing the earrings worn by the mother: they were Rabih, his mother, Miriam, his father, Awad, and his grandmother, Im Awad.”

Through her narrative experiments that flit in and out of her characters’ consciousnesses, Habib writes an intimate history of violence. She captures experiences of terror and loss that the mere recitation of journalist facts often fails to render. She reveals the effects of state terror as it is experienced in the minds and bodies of its targets. Most importantly, she teaches us what it is like to experience what many Palestinians in Gaza are now enduring, and reminds us that, while there are and will always be survivors of such horrors, the trauma is never forgotten.

While Samar Habib’s translation is meticulous and diligent in its quest for the right words to express the untranslatable traumas of war, there were moments where I would have liked to see more creative license taken, less literalist fidelity to the text. This issue arises particularly in the handling of footnotes. To take just one of many examples: details pertaining to the Palestinian folktale of the Green Bird that features in the story “Kawkab” are fascinating and relevant, but they feel wrongly placed, as if we are expected to read two simultaneous texts at once — Habib’s narrative and the translator’s notes — rather than to immerse ourselves in Kawkab’s story. So many of the details that are included in the form of footnotes as informational asides would work better if incorporated into the main text. That would have led to an English version that does not correspond in all particulars to the Arabic, but what, after all, is translation for? To produce a perfect replica of the original or to facilitate the reader’s entry into a text from a foreign world? I would wager that this is a work that wants its readers in any language to experience, in however mediated a way, the horrors of the war Israel waged in 1982, in order to better understand the horrors it is continuing to wage — against Gaza first and foremost, but also against the West Bank and Lebanon — as we speak.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)