An Iranian writer and translator in the heart of Tehran unexpectedly becomes a cat woman, attached to her pets well into adulthood.

Before the word “pet,” entered the Persian lexicon, animals rarely entered Iranian homes unless they happened in storybooks or on television. Our house, however, was one of the few where for a time an animal actually graced our lives, albeit for only a short time. By then I was already twenty years old and my brother and I had managed to convince our parents to adopt a dog. But Maman’s illness was getting worse all the time, which meant we had to leave the house with the backyard and move to an apartment in the heart of Tehran, where we could be closer to major hospitals and the doctors that she needed. This also meant the dog had to be given away. We were heartbroken and vowed never to bring animals into our home again, especially as Baba, in despair over Maman’s impending death, reversed his habitual optimism of years past and during Maman’s last months of struggle with cancer, refused any of his own medicines and doctor visits for his diabetes and kidney function.

The two of them died within 33 days of each other.

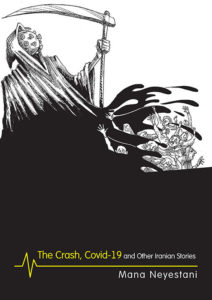

Life itself appeared smothered out of us. And things remained that way until demonstrations erupted on the streets of our city four years later. 2009. It didn’t take long before the protests against the government’s fixing of the elections were met with tear gas, incarcerations and killings. The glimmer of hope we’d enjoyed for a few months vanished. On top of that, a friend of mine disappeared, never to be seen again —though not in Tehran and not during the Green Movement protests, but in faraway Nepal. He had been an avid adventurer, a serious mountaineer, always going on long treks from which he’d send me photos. Before leaving this last time, he’d called to say he wanted a personally signed autograph of one of my recent translations. I no longer recall which book he meant. What I know is that he left and somewhere up there in Nepal he went missing in the Trishuli River while kayaking. I put his disappearance alongside all the other ones that had been happening in Tehran that year, though I still held hope he might come back again. I’d imagine him on the streets of our city, in the crowds of demonstrators, and even once dreamt that he came right up and tapped me on the shoulder and said, “Got you, Farnaz!”

You could say that that year was really just another depressing year in Iran, but even more so. For the first time in decades we saw that there were millions and millions of us who were angry, who wanted change, and who actually had the courage to march silently on the streets — not a peep, not a sound, not a shout — as a monumental gesture of dissent. We were the same people who could barely sit behind the wheel of a car in traffic for a minute before honking like mad and yet here we were, marching arm-in-arm in our elegant silence. There was true spark in the air and the color of our protest movement was a loud and proud green. But in the end, we were crushed, crushed hard, and hope disappeared once again.

With Maman and Baba no longer with us, plus the defeat of the Green Movement and the disappearance of my friend in the Himalayas, it truly felt as if there was no longer any chance of my climbing out of the dark well I’d been tossed into. It was then that Marilyn entered our home and, literally, pulled me out of myself. Even though my brother and I hadn’t forgotten the vow of four-five years earlier to never bring another animal into the house, Marilyn’s case was one we couldn’t turn our backs on. He’d found the kitten off the street, hungry and alone and instantly decided to bring her home. At the time we’d been watching the TV series, Prison Break, which was all the rage in Iran just then and maybe said something about the state of our collective minds too. In the series, there was a cat named Marilyn. It seemed as good a name as any, and so we decided to call the newest member of our household Marilyn.

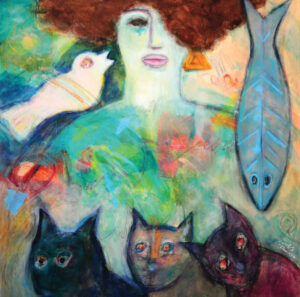

A tabby cat with a mix of gray, black, white and brown, Marilyn turned out to be hugely intelligent, playful and adept at keeping me from sinking back into that pit again. She’d fall asleep on my English-Persian dictionary and woke me up each dawn demanding we play.

Soon my brother’s job took him away from Tehran and so it was just Marilyn and I for a few years, but then, from one day to the next, the household exploded. My older uncle, the patriarch of the family, had decided that my younger uncle’s three daughters — fifteen, fourteen, and seven — were to be sent to live with me since their parents could neither get along nor come to an understanding about how to share the children between them. This was to be a temporary situation, but “temporary” turned out to be the next seven years of our lives.

Chaos came with my young cousins. Everything had to be changed — from the size of the fridge to the bulk and kind of food shopping I did, not to mention the number of beds and drawers and utensils. The size of the pots and pans grew and grew and every day there were more cups and saucers stuffed into the cupboards.

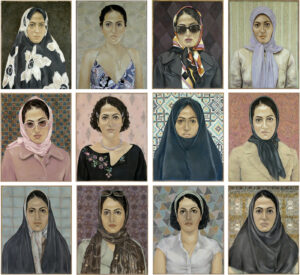

Our “thing” that we did together turned out to be cooking. Cooking created intimacy and immediacy. To say that my job turned solely into running a household of five women — myself, Marilyn and the girls — would be an understatement. For more than a year I put aside any other work to manage the fulltime job of running our lives. I was used to orderliness, while these kids were anything but. This was serious motherhood. Days would float by as if in a dream. It wasn’t a life I would have chosen for myself. The family had parachuted me into the situation. Marilyn, however, didn’t seem unhappy with the setup. She had her own corner and my cousins loved and spoiled her, especially the youngest.

During those years there were a lot of parties in our house. There was always a birthday, a valentine, a graduation or some other special occasion for the girls requiring a gathering. But party or not, the housework was 24/7. Cleaning, cooking, shopping, school homework, these all were jobs that were never finished; there was never a time when I could think: I’ll sit myself down and read a book. My translation work, which had been my livelihood, had gone completely out the window. I had to do something. I talked to two of my friends who were filmmakers and together we decided to rent an “office.” Now I went from being a “sudden” mother of three girls and a cat, to one with also a job and an office.

Then one night it happened that we had to leave Marilyn all alone in the house. On our return, she whined and meowed nonstop for the next day and a half. Something had to be done for the cat. And so it was that Mirza entered our house — a pure Persian breed, with blond fur, who had lorded it in its previous home among a clowder of females. But contrary to our expectations, Mirza’s arrival did not sit well with Marilyn at all. The addition of humans was one thing, but another cat, and a male at that, seemed like treachery to Marilyn, and sometimes I could have sworn she was looking at me as if I was guilty of the ultimate betrayal between us.

Mirza hadn’t been long with us when a friend’s dog happened on a sickly kitten hiding under a car. The dog, it appeared, had saved the kitten’s life but did not want her to stick around and made it known quite loudly. So it was that Yam-Yam also came to us. Now the house was truly crowded and Yam-Yam needed constant attention. I had to take her to the vet just about every other day for a while, until the vet declared there was no hope for the kitten and I should just take her home. It was then that Marilyn decided she would take on the same role of motherhood for Yam-Yam that I had taken on for my cousins. Yam-Yam not only survived, but she flourished.

There were seven of us now — me, the three girls and three cats. It wasn’t an impossible situation just yet. We each had our own corner and enjoyed or, in the cats’ case, put up with one another’s company. Until Yam-Yam grew, and as she did so did the attraction between her and Mirza. Before long Marilyn would take one look at the four new kittens that Yam-Yam had birthed, then one look at me and I knew what she was thinking: traitor. The cat population had at last outstripped the humans seven to four.

Neither the girls nor I were willing to give the kittens away. We all had to pitch in to make even more room. But when Yam-Yam and Mirza brought us another litter of five, we decided we would not name any of them so that giving them away could be a little easier. Three months later three of the kittens had been taken off our hands. The fourth let its displeasure be known so much that it had to be returned to us. And the fifth fell off one of my bookshelves, broke its leg, and ended up staying and becoming Kit-Kat.

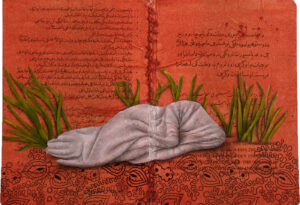

Kit-Kat was the gentlest of cats. As soon as I’d come home, he’d sprint over so I would pick him up and caress him. Even with a broken foot, he’d still revisit the cat litter after his brothers and sisters were done, making sure they hadn’t left anything exposed. At nights he’d put his little head next to mine on the pillow and go to sleep. And then one day Kit-Kat disappeared. My cousins called me at the office to tell me Kit-Kat had found a way to get to the neighbor’s balcony and probably from there down to the street. It hadn’t even been that long since we’d taken the cast off his foot, leaving it smaller than the rest. We spent untold days and nights looking for him on the streets, calling his name, and plastering flyers everywhere. Iranians are a cat loving people, but the flyers were still cause for a lot of jokes in the neighborhood. Sometimes I hit the pavements so long that it felt I was wearing brick shoes. Those were the early days of the news about the Syrian refugees too. On the internet we’d watch them dragging along the roads and valleys of their country with backpacks and bundles. I wondered about their heavy feet, their abandoned or destroyed homes, and if surely some of them — so near to us — had had to leave their own animals behind and move on.

With Kit-Kat gone, now it was me, the three girls, and eight cats. In time the girls’ mom managed at last to settle her life so that they could move back in with her. Three humans gone. Next went three of the cats to my brother’s home. It was me and five cats now, including Marilyn, who was happy to have more room in the house and queened it over all the others as she always had.

And then, just as suddenly as Kit-Kat had vanished, Marilyn came down with cancer. Marilyn’s illness took me back to the last months of Maman and Baba. How joy had left our home overnight. Back then I’d already, by default, turned into everyone’s parent in the quickly diminishing house of Maman, Baba, my brother and me. Yet just to keep hope alive, I had also begun volunteering at a medical center for children with cancer. Even though more than once I did witness miracles of recovery in that center, Maman’s irrevocable march toward death made any sort of cancer therapy forever suspect to me, including Marilyn’s treatments. Nevertheless, dutifully I took her back and forth to the vet, where she also had to endure a difficult surgery, until the day the metastasis of her condition became irreversible.

One human, four cats. Those are the numbers in my home now. Sinking into despair can happen in an instant. I am aware of this. My four current roommates keep me from even considering taking that plunge. Every day I imagine I’ve spotted Kit-Kat somewhere on the frantic streets of Tehran. Time has passed and many Syrians are still traveling with their bundles and backpacks from one country to another. Alongside them now are the Ukrainians, the Afghans, the Palestinians, the Lebanese and the people of Sudan …

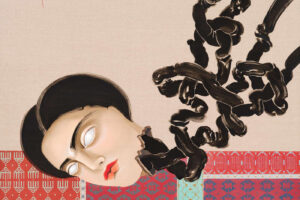

I think about tired feet and lack of shelter and homelessness, and I follow stories of abandoned animals in this war and that war. Sometimes I even imagine that surely over there, right there on the other side of the busy boulevard, must be my friend, the one who disappeared in Nepal, about to sprint over to surprise me and yell “hi!” I think about the year of his disappearance, and of crushed rallies, of hope vanished, and this: not silent marches but silenced ones. And, finally, there’s Marilyn, her picture on the wall of every place I have lived ever since she first came into my life to rescue a single human from an unjust world.