Djinns come to life in a broken home in bustling Istanbul to embody intercultural and intergenerational tensions, veiled by silence, in Fatma Aydemir’s grippingly realistic family saga.

Djinns by Fatma Aydemir

Translated from the German by Jon Cho-Polizzi

Peirene Press, 2024

ISBN 978191680602

Identity crises emerge in banalities of everyday life in Fatma Aydemir’s haunting Djinns, a novel exploring questions of home in migration, belonging, shame, sexual desires, gender confusion, feminism, motherhood, and other existential meditations.

Dschinns or “djinns” in English is a Germanized, and subsequently Anglicized, false plural of the Turkish collective noun cin. Its original Arabic root means “to conceal” and “to descend into darkness” with other forms signifying “madness” or even “paradise,” but it has become globally understood through the mythologizing of invisible beings inhabiting Earth known as jinn.

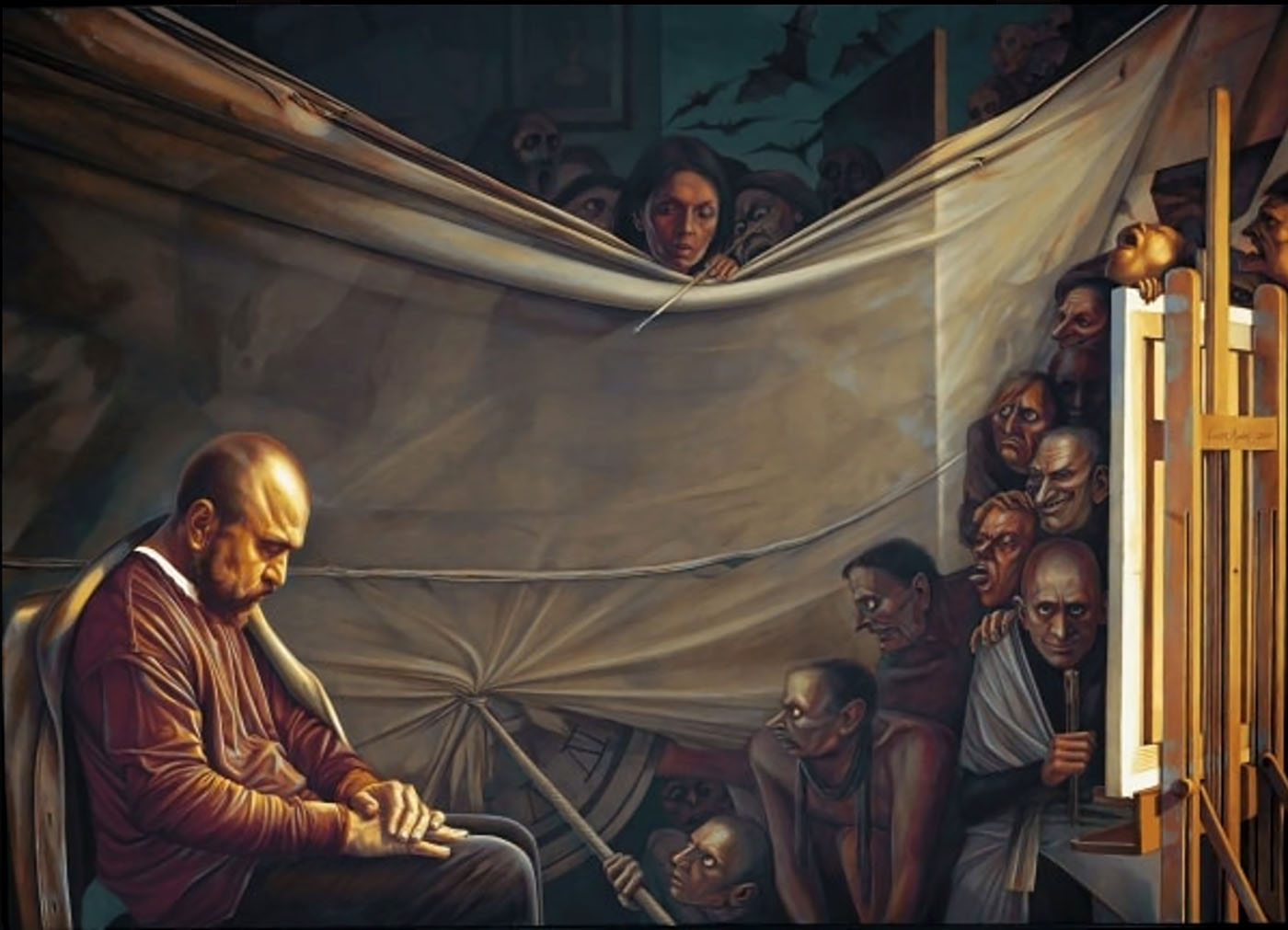

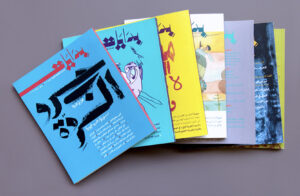

Jinn are a rich well of metaphoric opportunity in literature, which, in its best expressions, can convey life’s incorporeal mysteries. For example, the One Thousand and One Nights comes to mind. In Western cultural consciousness, the archetypal genie from “Aladdin,” which Antoine Galland added to his French translation of the cult text having been told it by Syrian storyteller Hanna Diab, is a key example of the crucial role of translation in transcultural exchanges. The incorporation of jinn into modern literature is popular, often to comment on contemporary reality. Examples include Egyptian artist Deena Mohamed’s graphic trilogy Shubeik Lubeik, or Your Wish Is My Command. Jinn are also present in the magical realist literary worlds of Turkish writer Latife Tekin, whose debut novel Dear Shameless Death (1983) follows a girl’s move from superstitious rurality to the “modern” city.

Fatma Aydemir was born in Karlsruhe, Germany to children of Turkish “guest workers.” She called her second novel after these beings to explore meaningful silences, intercultural and intergenerational clashes, and identity questions in a grippingly realistic family saga loosely based on her own.

Those who can should read the original German, but Aydemir’s novel is now available to a global audience thanks to Jon Cho-Polizzi’s fine translation. In an email interview, the professor of German and Comparative Literature at the University of Michigan wrote: “The books I translate are labors of love. I translate them because I think they are important and make critical contributions to contemporary German social discourse that readers in the wider world should be aware of.” Cho-Polizzi engages himself politically “by highlighting different literary voices that move us past … tired expectations” of world literature. Djinns was first published in the U.S. and recently brought to the UK by Peirene Press.

At the launch of Djinns’ UK edition at London’s Goethe Institut, Aydemir explained that after throwing away multiple attempts at a light-hearted romance, she turned to writing the story of a character loosely based on her grandfather. Hüseyin Yılmaz returns to Türkiye after spending the better part of his life working in Southwest Germany as part of the 1960s and 70s Gastarbeiterprogramm that saw hundreds of thousands of Turkish workers fill a labor shortage in the post-WWII German economic boom. After decades of back-breaking factory work — and ironically though unsurprisingly little experience of Gastfreundschaft, or hospitality — aged 59, he buys an apartment in Istanbul. Aydemir writes in the first chapter:

“Hüseyin! You’ve finally found a place you can call home … Germany was not what you had hoped it would be, Hüseyin. You’d hoped for a new life. But what you received, instead, was loneliness … How the time flies … You want to breathe, Hüseyin. You don’t want to die. Not now, even though you are devout.”

His wife and four children follow him to Istanbul, not for the homecoming he had dreamt of, but for Hüseyin’s funeral. In a tragic early twist in the story, he dies from a heart attack as swift as his brief taste of retirement freedom, on the day he moves in.

With her main character expiring within the initial pages, Aydemir turned a short story into a substantial page-turning novel by giving voice to the next generations: her parents’ and her own.

Cacophony of silence

The short opening chapter suits a man of few words while still alive. Hüseyin’s death opens a void that substantiates his life beyond the silence that governed it and is embodied by the otherworldliness contained in the apartment, which his widow Emine considers “cursed.” One of their children describes the dynamics of this space as follows:

“The silence of this room hurtles around his ears like a screaming siren, like a fire alarm. Like the sound of rolling tanks … This family never argues out loud. In this family, fights always happen this way: with meaningful glances and diverted eyes, with all those things that can never be said and so hang all the heavier in the air between them … Something must have happened. Something so terrible there were no words for it. And now Hüseyin is gone, now here they all are, those he left behind, sitting around with his only legacy. Silence.”

Each subsequent chapter is told from the perspective of the family member it is named after, starting with the youngest teenage son Ümit, followed by the eldest daughter Sevda, then Peri and Hakan, the middle two. Emine, the mother, gets the final word.

The novel progresses chronologically in time, from Hüseyin’s death through his family’s journeys to Istanbul for his funeral, until a both crushing and uplifting ending. Each character’s account moves between inside and outside lives, revisiting memories that together mold the family’s history and present.

The Yılmaz family’s Kurdish origins are suppressed by assimilation policies introduced under the Republic of Turkey. Notably, Kurds were referred to as “Mountain Turks” for the better part of the 20th century, and Kurdish languages were banned after the 1980 military coup that followed more than a decade of political violence and ever-more-right-leaning nationalist tendencies. Hüseyin’s legacy of silence is rooted in this forced renouncement of his own language and identity.

As distant relatives and friends flood the apartment to mourn its deceased owner, the language they speak mystifies the youngest son, Ümit. He guesses, correctly, that it is Kurdish, “because the Kurds are always in the news these days.”

Ümit’s panic-inducing sensory disassociation from his surroundings through his unfiltered observations and unlikely associations establish a distance between his newfound community and the reader. Introducing “a mountain of dusty grandma shoes” in the hallway, he then compares the black-cloaked praying women to zombies in the horror films his brother watches.

Aydemir balances humorous stereotyping and complex nuance as she blunts the orientalist razor’s edge between authenticity and modernity, giving space to the exploration of agency in existential questions of identity and home in the context of migration.

Cracking tiered terror

The Yılmaz family leaves Türkiye only to reach Germany, a nation mired with its own history of genocidal silence. At the book launch, Aydemir pointed out that, as she learnt from interviewing immigrants in Germany, many of them became aware of the Holocaust concurrently with their first-hand experience of racist xenophobia in Germany. Perversely labeled as “Turks” in Germany, the Yılmaz family and many other “Turkish” immigrants are made to re-live the very persecution they fled.

Hüseyin’s grandchildren are left alone one night, when their father goes out drinking instead of looking after them while their mother Sevda worked a night shift to pay the rent. They are rescued from their burning building instants before being “Incinerated. Burnt to dust. Exterminated,” as their mother imagines in a picture gruelingly evocative of Nazi extermination camps. With this incident, Aydemir recalls the fatal arson attack against a Turkish family in Solingen, Western Germany, in 1993, and brutal acts of racist violence that take place around the world to this day — from last summer’s anti-migrant riots across the UK to the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

Djinns unravels layers of systemic terror that the most vulnerable individuals — many migrants foremost among them — live under, revealing in the cracks lives that cannot but be subversive to homogenizing myths. These stories are vital in today’s bulldozing political landscape. The vote gains achieved by the extremist Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), representing the steepest rise in popular support for the far-right since WWII, threaten the collapse of the Brandmauer, a metaphorical “firewall” denoting mainstream political demands and strategies to protect German democracy against the far-right.

Sevda’s younger sister Peri asks, “Is it easier to worry about djinns than to worry about Nazis?” She is the most politically aware and outspoken in the family, taking it upon herself to educate her mother Emine about feminism and mental health. She accompanies her to a therapy session, only for Emine to walk out five minutes later, confounded, and resorting to her usual recitation of suras. Aydemir gives space to various grief coping mechanisms, levelling spiritualism with intellectualism. She also deconstructs the more-often problematized image of the young male migrant through the older son Hakan.

His journey to Istanbul is a breakneck road trip “down the A8, blasting past roadside churches, grazing fucking cows and the Chiemsee. He’s still on the German autobahn: anything goes. The only freedom this piece of shit country hasn’t taken away yet.” But in the infamously conservative state of Bavaria, the police arrest him.

“The first time the cops brought Hakan home” was for tagging N.W.A.’s FUCK THA POLICE in the train station. His American hip-hop-inspired slang meets the harsh AUSLÄNDER RAUS (“foreigners out”) tags that Jon Cho-Polizzi kept in German. The translator explained, “most of the translation work I do has some sort of transnational element where multilingualism plays a role. This is part of the experience of global modernity, and it’s really important to preserve this even in translation — though of course this becomes difficult, particularly in German-language literature, where a lot of the code switching actually deals with the use of English in a German text. One solution that I’ve come up with is to turn this around and re-insert German words to remind the reader that this is a translation.”

Language is Hakan’s only power, however ineffective in the face of institutional power: his rhythmic and poetic slang reflects his deep knowledge of the dark layers of the society which he sardonically mocks. He re-appropriates the ethnic slur Kanake, putting on “an Oscar-worthy performance” when he interacts with his girlfriend’s father, “leisure-time Nazi” Günther. All for the sake of an Elternhaus, or “family home.” The compound noun in German emphasizes the entanglements inherent to the notion.

The mother Emine is a looming presence in each of her children’s accounts yet only given a voice in the last chapter of the novel, reflecting the societal favoring of the role of “mother” over the woman as an individual. She does not narrate her own chapter but rather is addressed, like Hüseyin, in the second-person du, “you” in English, which underlines her shadow status as family pillar while simultaneously honoring her silence. Aydemir nevertheless establishes a distance between her voice and that of the older generation in a compassionate critique of their silence and inaction.

Language haunts

Aydemir’s use of specific vernaculars and insertion of Turkish words like şekerleme (“sugar sleep”) not only adds to the text’s poetic quality and creates a creative cultural meeting space but also adds a veil of silence and obscurity to the text. For example, the gender-neutral third-person pronoun o creates ambiguities to build tension in a plot mystery that unravels gradually and satisfyingly to ultimately shock the reader.

Jon Cho-Polizzi’s translation continues Aydemir’s linguistic fluidity. He added a glossary and explained, “Fatma Aydemir is making a specific intervention in her novel by not translating Turkish words for a German audience. Because a German readership should know these words. In the U.S., I might make a similar argument against translating Spanish in a novel … But to transfer a work out of its original context through translation also introduces new questions and assumptions about the readership, and the same intervention is not made by a minoritized language in a new cultural context. So I tried to negotiate a balance between staying true to the feeling of the source text, while also making the intervention intelligible to a new readership.”

The translator into English holds, Cho-Polizzi stressed, “a huge responsibility,” that he undertakes through “experiential” research: having lived in Southern Germany and spent time in Frankfurt and Eastern Turkey, he also went on research trips, including to Istanbul. The existence of a “literary kinship” between author and translator is key to the process—and so are multilingual and multicultural networks.

Cho-Polizzi met Fatma Aydemir during their collaboration on the open-access English translation of Eure Heimat ist unser Albtraum (2018; Your Homeland is Our Nightmare, 2019 / 2022 in print), an essay collection that deals with many of the issues, specifically in what relates to migration and identity, Aydemir explores in her fiction. He then translated a sample of Dschinns for New Books in German, which highlights German-language literature for translation into English. This season’s picks include German Iranian Hengameh Yaghoobifarah’s experimental queer diaspora piece Schwindel (‘Dizzy’) and Saudi-raised Rasha Khayat’s Ich Komme Nicht Zurück (‘I’m not coming back’), which also explores silence in family, friendship, and love. Khayat repeatedly writes: “Entire books could be filled with all the unspoken words.” Jinn, or Djinns, give shape to the invisible, just as literature gives words to the unsaid.

Hüseyin’s death brings the scattered and shattered family crashing and clashing together in Istanbul’s cacophony of car toots, music, people, the azan, etc. The domineering “weapon” of silence is challenged by the children’s voices and the family’s heads-to-heads. But as Libyan writer Najwa Binshatwan declared, “words are like gunpowder,” and in Aydemir’s novel, as “the ragged shreds of their words fly past,” they progressively make space for language on the emotional battleground.

Mahmoud Darwish once wrote to his friend the poet Samih al-Qasim: “Do you still believe poetry (qaṣā’id) to be more powerful than planes?” While it is difficult to hold on to this belief in the near-impotence vis-à-vis past and current political terrors, Aydemir proves literature’s power to move the reader from the inside out.

As Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in The Message, “The goal is to haunt — to have [the reader] think about your words before bed, see them manifest in their dreams, tell their partner about them the next morning, to have them grab random people on the street, shake them and say, ‘Have you read this yet?’” Fatma Aydemir’s novel Djinns is haunting.

Though the Yılmaz family’s silent issues remain unresolved by the end of the novel, they have been voiced, spelled out for the reader to think through past and current societal as well as personal questions that are perpetually obscured by silence and even distorted by lies and mythmaking.