gethan&myles

Fever Dreams

“Marseille est une ville qui ne ment pas,” (“Marseille is a town that doesn’t lie”) she said before leaving it for good.

And she was right. And that was her reason to leave. And ours to stay.

Marseille shows you everything — if you take the time to look hard, to explore, to get yourself lost in its twisted streets, its improbable stories, and venture over its suffocated hills into its chaotic, overlapping, labyrinthine neighbourhoods.

It’s a town where poverty is always present. And riches too. The quartiers nord —a place of drug deals, gang murders (the infamous ‘règlements de compte‘), chronic unemployment and chronic neglect. The Roucas Blanc, the white rock where Marseille’s millionaires retreat to barely-concealed summer-palaces and lavish villas. A rich-poor, north-south divide with the once thriving commercial artery of La Canebière as the frontline. Inequality and injustice aren’t hidden here — they rub shoulders every day under the narcotic southern sun.

And yet, it is also a place where everything feels possible. Is possible. At least until you try to get it done today rather than tomorrow.

Marseille is la Ville-Sans-Nom — the town with no name — erased from the post-revolutionary maps to protect the new nation from its anarchic, seditious ways. Too revolutionary for the revolutionaries? It is eternally lawless, eternally ungovernable, “indisciplinée” as Didier so rightly said when we first arrived —struggling to take in the double, triple-parked cars, the ever-present tourist-baiting dog shit, the kleptomaniac postmen, the litter litter litter and the helmetless shirtless moped-riders wheeling the wrong way down one-way streets.

Marseille is a place of transit and transition. Always moving but never going anywhere. A potent, pokey cocktail of French, Italians, Corsicans, Spanish, Armenians, Algerians, Tunisians, Moroccans, Comoreans, Malians, Madagascans — and all the other people that were passing through but then never quite did. Seduced or swindled or just somehow stuck by the sticky, sapping aura of this port in a storm.

Founded by the Greeks (more foreigners) 2600 years ago, Marseille is France’s oldest city. And France’s least French city.

Marseille is not Paris. In fact, it’s the anti-Paris. It dabbled with a couple of Parisian, Haussmannian boulevards —so much more practical for shooting the unruly masses than the tangled alleys that weave the city together. But in true Marseille style they built the gates to the fancy new courtyards too narrow for a carriage —so none of the bourgeoisie moved there, and the first of so many attempts at gentrification, rebranding the beast, failed.

No, Marseille is certainly not Paris (don’t mention PSG). Not France even. Looking towards the setting sun, drawn south, across the Mediterranean to the Maghreb shores and beyond.

It is a town of nuclear sunsets —falling day after day through pyrotechnic polluted skies into the weary bruised stoic Mediterranean.

The sun shines here. People shout. Laugh. Get angry. Laugh again. Play pétanque. Drink pastis. Gesticulate madly. Get excited. Get angry again. Cry. Laugh again. Complain complain complain. Laugh again. Shout again. Shrug. Embrace the clichés of their blue-sky-kissed day-to-day. It could always be better. But it could definitely be worse.

“Marseille est une ville qui ne ment pas.”

Often there’s more truth than you need. More than you could ever want.

Except… Marseille does lie. All the time. So in-love with its stories and its perpetual mythologizing that its truth is a permanent and ever more tantalizing fiction. Not so much post-truth, as poly-truth. It’s not even a city at all —just a bunch of villages and roads that rub hard shoulders with each other but never truly meet up. It is a liminal paradise. Never one thing or the other but all of them at once — and with a double pastis thrown in to trouble the waters even further…

And that’s without even mentioning the blessed virgin Bonne Mère and her alter-ego, the hard-drinking hard-loving cagoles who worked in the sardine factories and gave the men as good as they got. Or OM: the sacred mantra of the fanatical Olympique de Marseille supporters; obsessed with distant glories, always hoping, believing the impossible — that this season will be different; that this season will be like it was before. Nostalgia is our oxygen. We breathe it to survive. Or the Calanques —the earthly paradise where the town hid its toxic factories (lead, arsenic, sulphur, hydrochloric acid… who knew making soap, the famous Savon de Marseille, could be such a dirty business?) for a hundred years, and where the pollution will live on for thousands. Or local politics —where Shakespearean tragedy and farce rub along nicely, the same old hands oiling the wheels for decades on end. Or the sea —the ever present, taste it in the air, dump your litter in it, wash away your worries in it, love it and fear it, just stand in front of it and watch it, wait for it, for something. Or the Nazis —so infuriated by the uncontrollable, dirty, mongrel spirit of the city that they blew up its ancient heart, dynamited swathes of Le Panier to rubble. Or heroin and the French Connection — wilder, more engrained and more dangerous than Popeye could ever know. Or hip-hop — the mouthpiece and the motor, the illusory treasure map for generations of young men for whom the big skies and the big seas aren’t a way out, but a wall. Or the mistral, scouring the skies and whipping our heads — le vent qui rend fada, the wind that makes us mad —an elemental force so perfectly suited to the excesses and imbalances of the city that it’s hard to imagine it howling anywhere but here. Or Zidane, Artaud, Cantona, Pagnol, Tapie, Izzo, Flamini, Rimbaud… Footballers and writers. Dream manufacturers.

Marseille is a fever dream. In ten years living here that expression returns again and again. Now. Writing these words. It is clear why. There’s a strange multi-sensory elation this city can so quickly create, and so quickly destroy. Marseille’s fever dream is kitsch and carnal, implausible and irresistible, tender and brutal and beautiful… Energy and light. Sun and wind and sky and sea. A euphoria of blues. Forget America, Marseille’s dream makes your eyes, your skin, your insides ache. It’s an addictive sucker punch of joy and pain. Pain and joy. Never enough and often too much.

Marseille is all of that. And then none of that. A town of hypnotic contradictions where everyone sees what they want. And when they don’t, they look back out to the sea, take a deep breath. And try again.

And if that doesn’t work, they leave. For good.

Until they come back.

Gold Fever

It’s a strangely pleasant feeling of vertigo. The ground shifting. It’s not the 10,000 euros worth of gold, strewn over the breadcrumbs and congealed baby-food on our kitchen table that gives the pleasure. We don’t even like gold jewelry (though the effect is quite ‘casual-bling’)… It’s the three piles it’s pushed into: Like, Really like, Love. Specifically, it’s our desires for each pile… We’re trying to give this jewelry away — which is odd enough — but it’s the Love pile that we’re most desperate to give away. We’ve created a system where the value isn’t the object, but the idea of the object; its meaning; its story. If we don’t manage to return it to its previous owner, we’ll never get to know its story. And all we’ll really have on our kitchen table is a pile of shiny yellow stuff. Admittedly, a pile that’s still worth ten grand — but we’ve made it so that doesn’t matter. The possession we covet most has become the one we least want to keep…

Some time ago the Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée (MUCEM), Marseille, asked us to create a participatory work for their summer exhibition about gold. We generally like to make work for and with people who aren’t considered as a typical “cultural audience” —and we have a deep love for our adoptive home, Marseille; so we set about making an artwork that celebrated this wild, contradictory city and it’s equally wild and contradictory inhabitants. Marseille is a above all a port, a gateway where the North meets the South — “Europe say hello to Africa. Try to be nice…” — a nexus of historical and actual migration; and we knew that in the specifics of these Marseillais stories, we would be lead to the wider, ever more messy truths of a world that has always been in movement, of human beings doing what human beings have always done: wanting hoping, for more. And so it was that over the course of a year we spent ten thousand euros on gold jewelry. And then gave it away. This money represented both the production budget and artists’ fee (the bit you pay the rent with). In many ways it was a foolish, absurd endeavor. But often they’re the best ones.

The story starts in a concrete, 1970s office block. We’re sitting apprehensively in a big, ugly, almost-empty assembly room. Forget exotic surroundings and the romance of the venerable auction houses. This is the fortnightly auction at the Crédit Municipal. A strange and arcane space where a select group (and us!) come to buy vast quantities of gold.

The Crédit Municipal is, to put it simply, a state-run pawn shop. To the English-speaker the word pawnbroker evokes images of a shark, a predator, someone who profits from the misfortune of others. So, when we came across the Crédit, the “aunt” that the French euphemistically say they’re heading to with the family jewelry, we were moved by the intelligence and the humanity of the French model. The Crédit doesn’t aim to make a profit, but to cover its costs. Its function is to offer fairly priced micro-loans to people in financial difficulty. Of the hundreds of thousands of loans made every year, less than five per cent end up defaulting. If they do, the pawned object which guaranteed the loan is sold at auction, with any profit (sale price minus the initial loan and any unpaid interest) forwarded to the person who pawned it. In its own words the Crédit sees itself as a banque à vocation sociale. Oxymoron anyone?… Lazare / The Space Between How Things Are, And How We Want Them To Be is inspired by this little-mentioned public institution and its beautifully elegant inversion of an aggressive, exploitative, free-market principle (Kick ‘em when they’re down) into a socially-responsible, compassionate one (Maybe help them back up?).

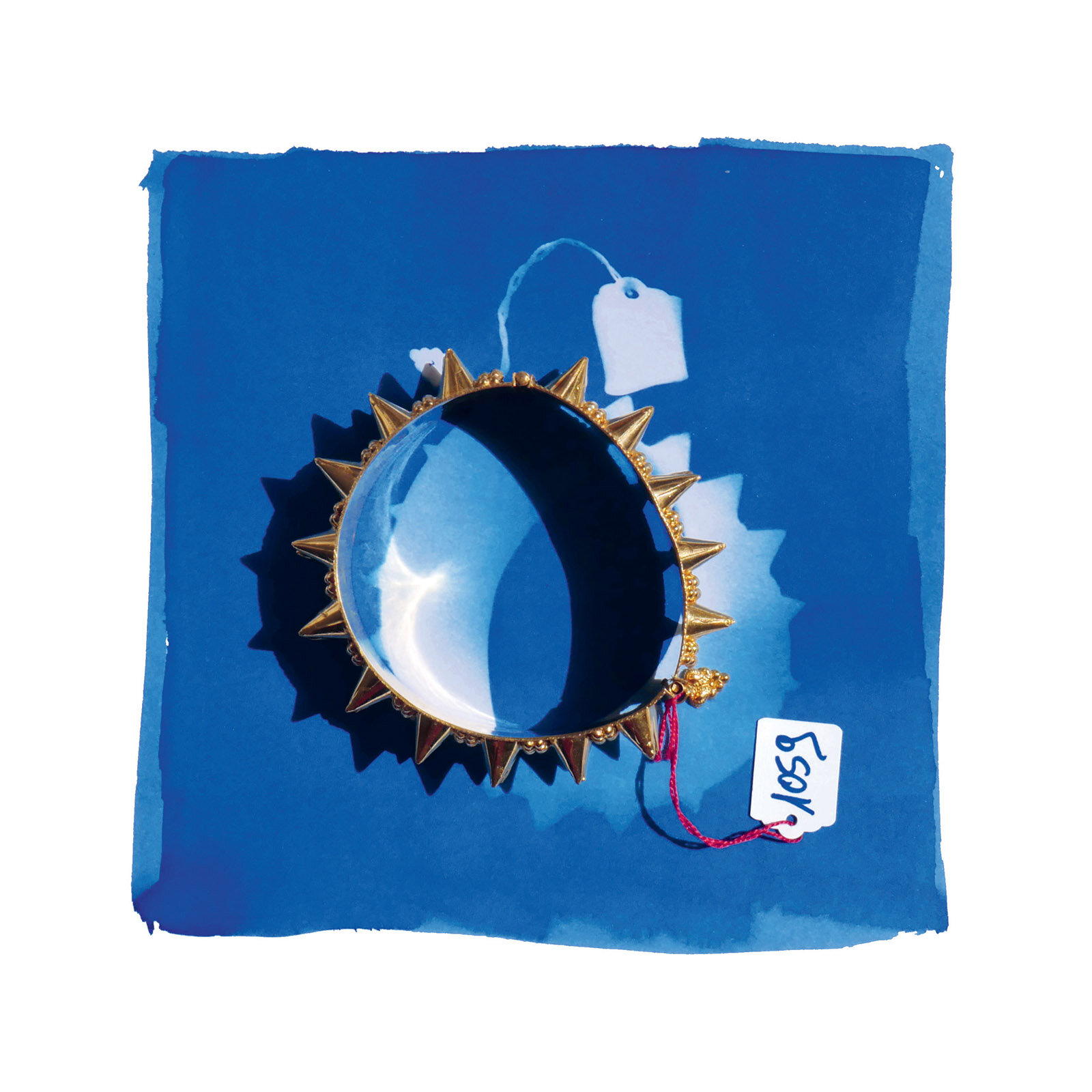

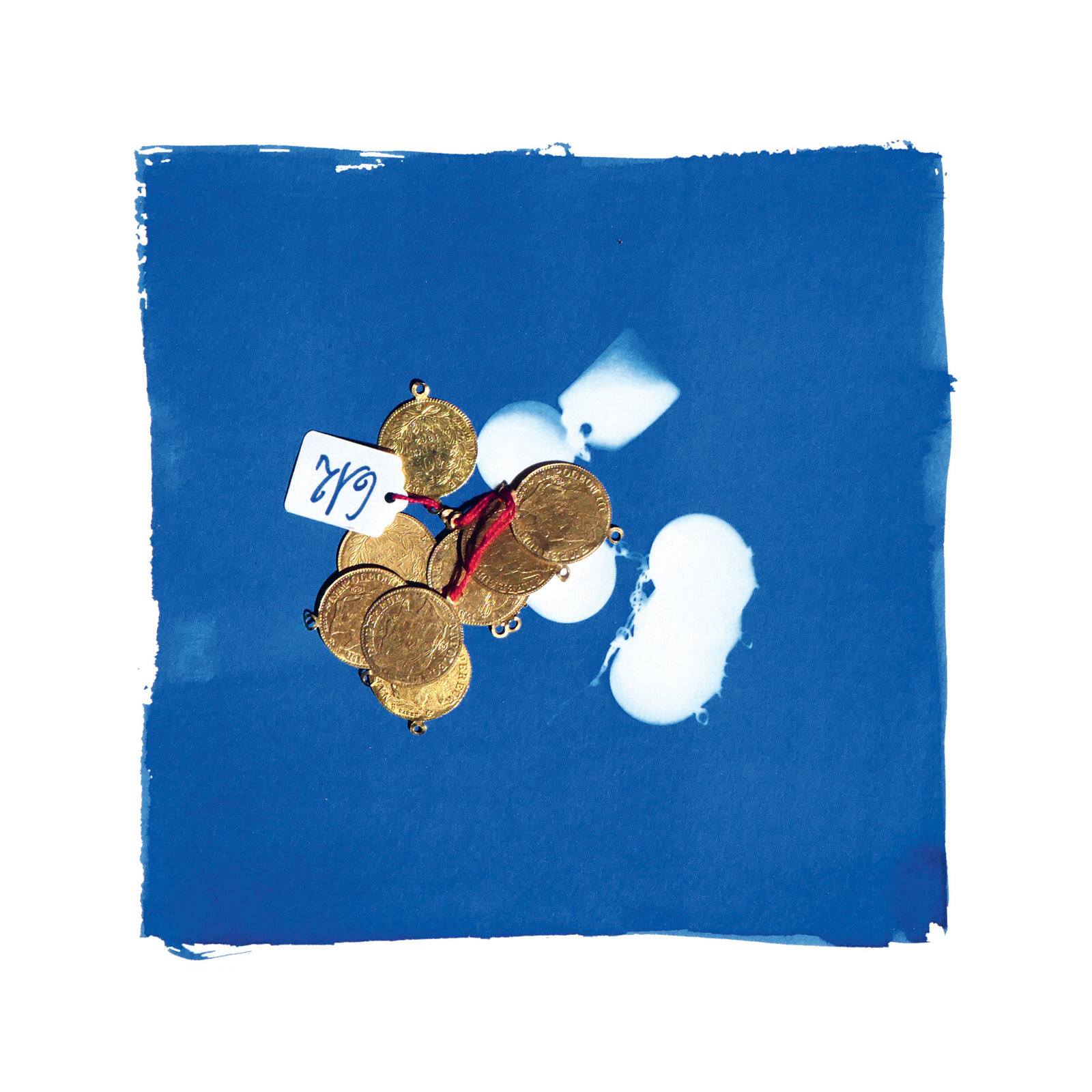

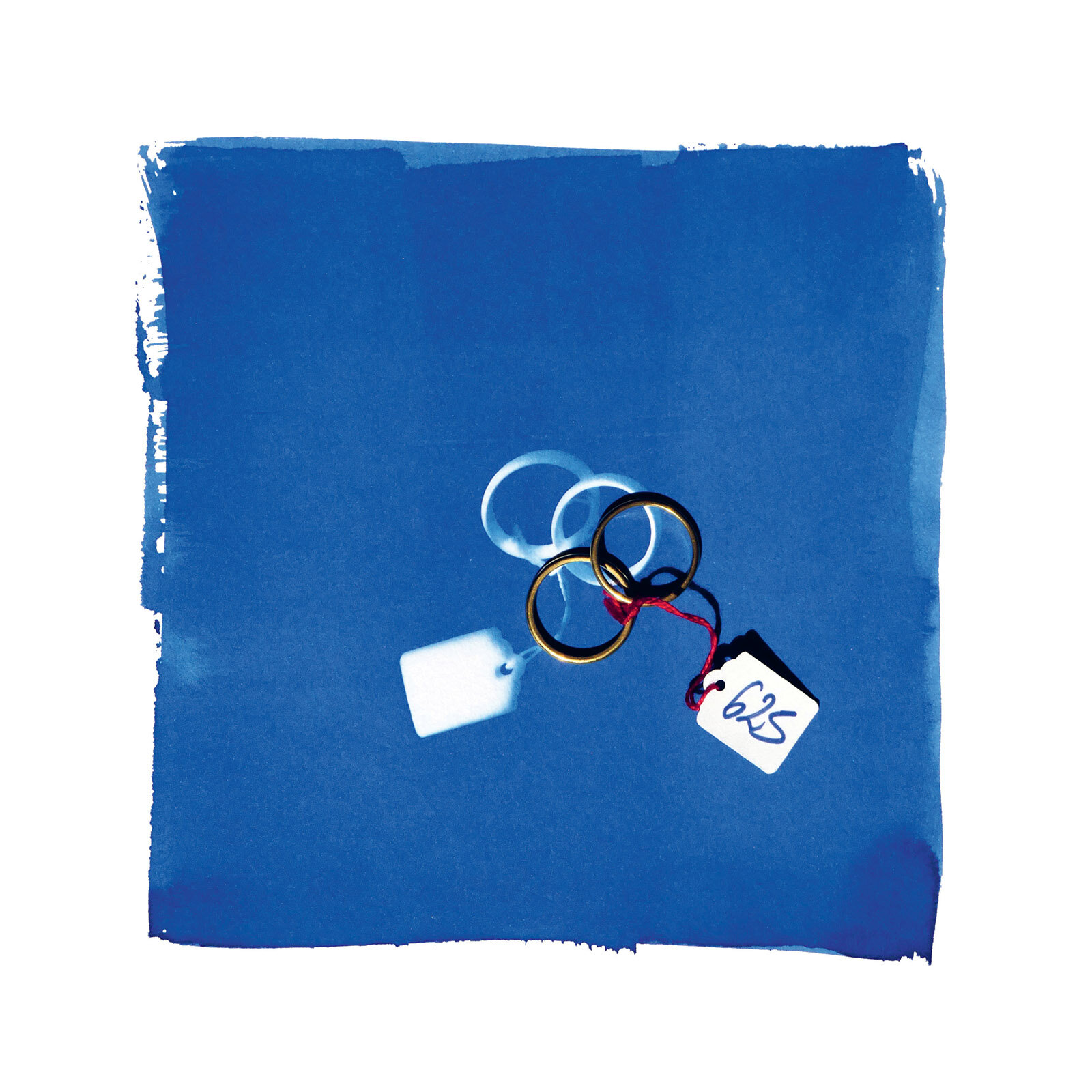

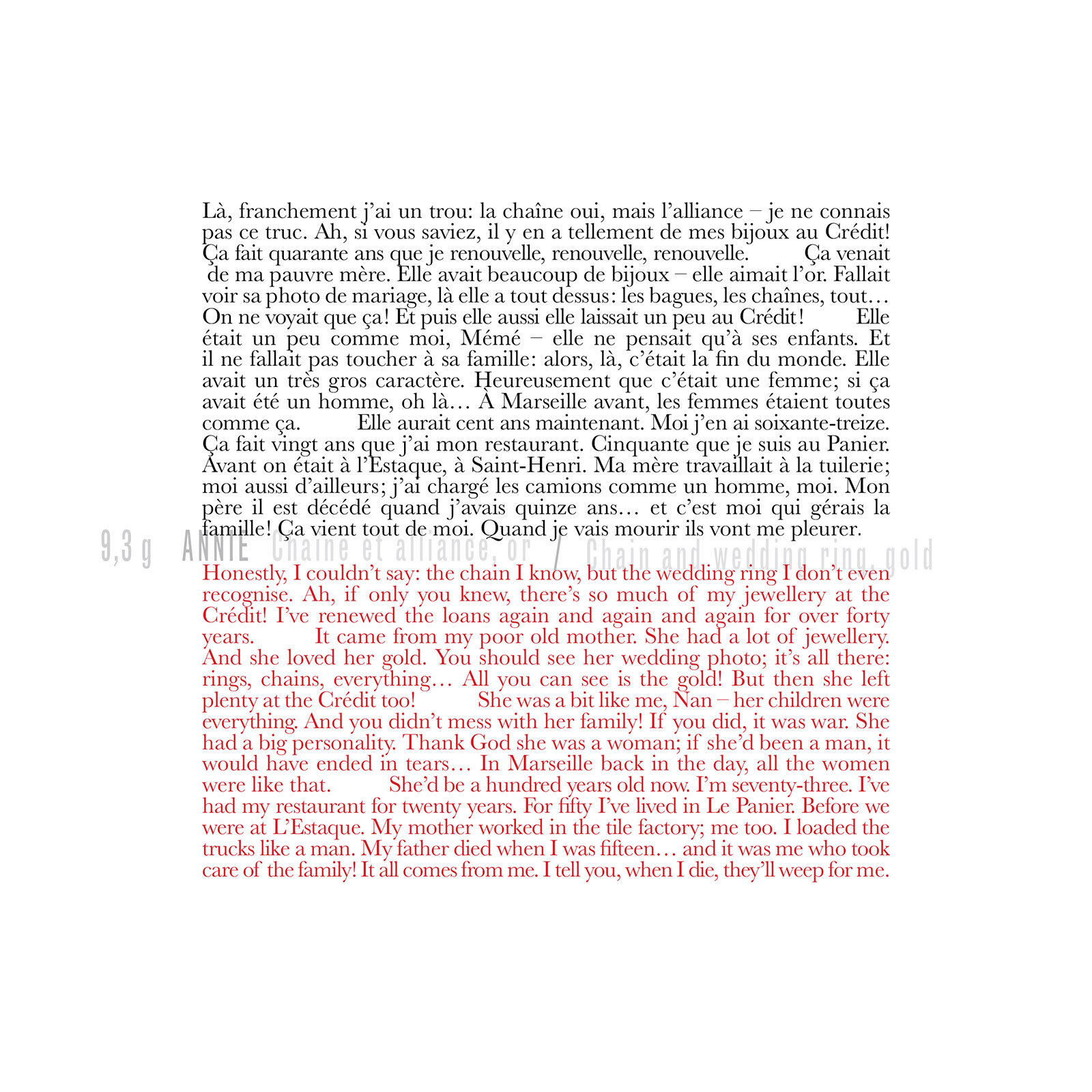

The jewelry used in Lazare was purchased at the Crédit Municipal de Marseille over the course of 12 months. At these auctions the description of an object is concise (to put it politely): “Bracelet, gold, 38.3 g”. Why? Because the only detail that matters is its weight: the vast majority of the jewelry is bought by gold dealers to be melted down. Age, craft, beauty count for nothing. In one brutal acquisitive act its form, but also its “meaning”, its human history, will be erased. Where did it come from and what does it represent? What sacrifices? What journeys? What joys? What hopes?

Outwardly, the auctions are pretty depressing occasions. On the morning of the auction the 1,000 or so lots are “displayed”, via their brief description and a blurry snapshot, in a tatty A4 print-out. A sad account of a moment of mass loss. You never get to see or touch the object you will or won’t buy. We made all our selections by instinct. The grey and beige interior and the neon strip-lighting don’t much lift the mood. Nor does the emptiness of the room. A funeral that no-one turned up to… And yet the sales are often surreal affairs. “Folklorique!” declared a weary auctioneer after a session that was particularly full of pantomime rage and giggling fits. The key actors are the gold dealers. They’re always the same three: Muscle Boy, Big Mouth and Chouchou (teacher’s pet) as Big Mouth calls him. Names have been changed to protect the (probably-not-very-) innocent. Together they’ll buy about 95 per cent of the lots. They buy gold at the market rate and not a cent more —so as soon as we bid anything above that we’re almost certain to win. The dealers are in a hurry —they have hundreds of lots to buy, and an urgent date with a pastis at 6 pm — and they heckle, harry and cajole the auctioneer at the slightest sign of a pause. This makes for a slightly crazed energy, with the auctioneer in the role of indulgent school-master and them as the unruly pupils. Sometimes the strangeness of it all gets too much and the dealers end up in fits of hysterics. An empty funeral perhaps, but a lively one at least.

And so it was that we discovered that spending ten grand of someone else’s money is alarmingly easy to do.

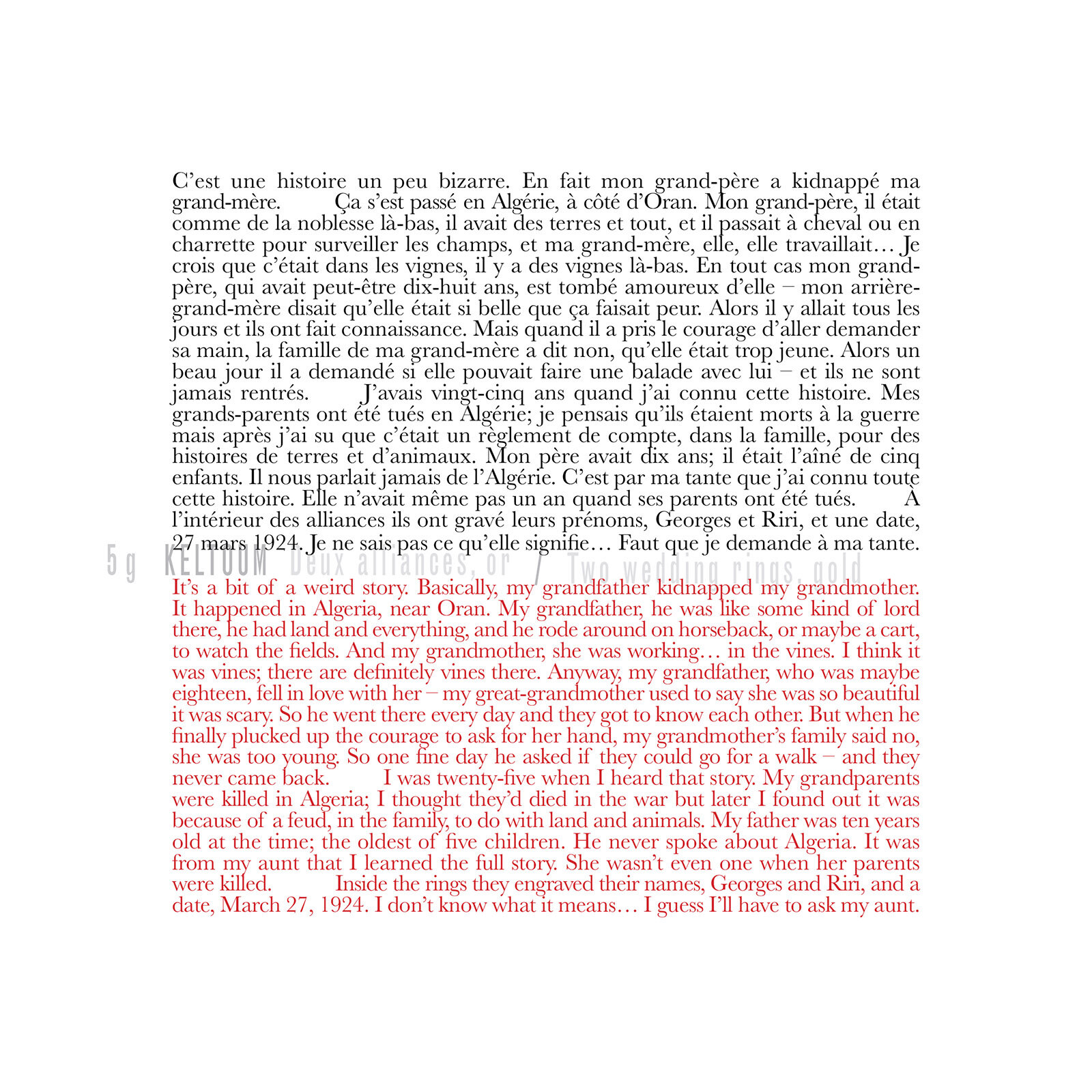

Next, and with much patient help from the Crédit’s administration, we spent many, many months searching for “our” jewelry’s former owners. “Two unhinged artists have bought your jewelry and want to give it back” went the official letter from the Crédit. (More or less). Surprisingly (or not), it was very hard to get people to believe this was not some low-rent scam or a sting for a TV show. Hence the need for our kitchen-table priority piles —there were only so many times we could ask the Crédit to recontact the owners (for reasons of anonymity the first contact had to come from them). “This kind of thing just doesn’t happen,” was the sceptical response from the 15 people we finally met. Over a coffee we explained the project — emphasizing that this was not charity, but exchange; the worth of the stories being at least as great as the monetary value of the object — and they talked about the previous life of their lost treasures. Generally, they started reluctantly, then talked at great length. These meetings were often extremely powerful and emotionally-charged.

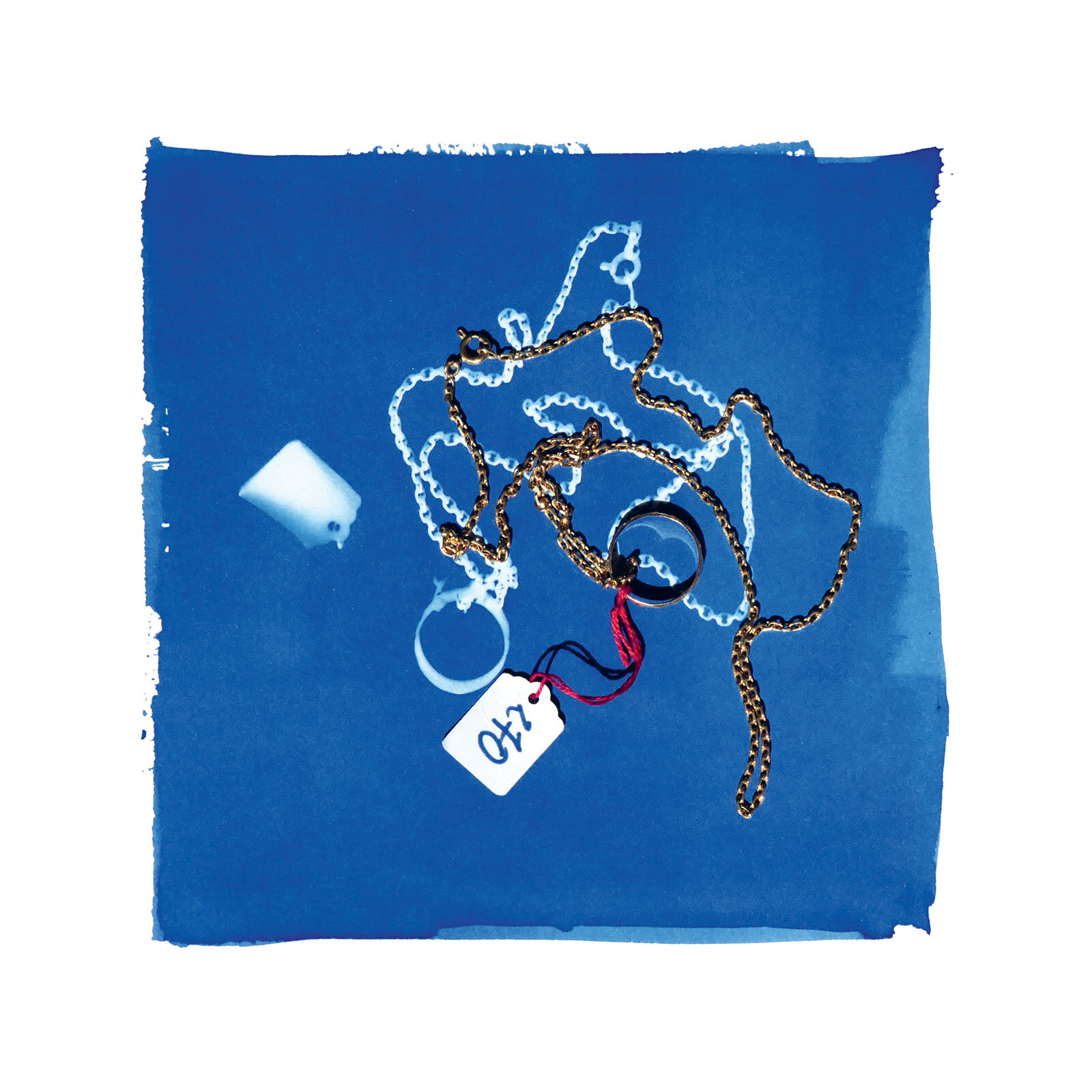

Subsequently the objects and their stories were displayed at the MUCEM’s grand summer exhibition. Holding their own alongside ancient gold crowns and burial masks, haute-couture dresses and modern art masterpieces, they were each placed in a transparent square vitrine, suspended in thin air on a made-to-measure metal stand, the back of the vitrine lit up by a blue cyanotype. Invented by John Herschel in 1842, the cyanotype is a one-off image created by the sun and ‘fixed’ by water. Unlike any other photo, these blue images have a peculiarity: if their color fades you simply store them away from light and their original blues return. They live again. The cyanotypes for Lazare… are photograms, prints made without a camera using the Marseille sun and the water of the Mediterranean. Thus, they depict the “lost” jewelry through its shadows – by its absence.

Sometimes people would queue in front of the vitrines to read the stories. Sometimes they would cry. Sometimes they would share their —slightly embarrassed —memories of a family trip to the Crédit. Many of our co-creators came with us to the opening night. Together we met the curators, ate the canapés, drank the wine —for some it was their first visit to a museum. One of them, Sandès, commented that she might be “less thick” after going to an exhibition — chief-curator Marcel replied in his beautiful, Gallic purr, “Oh I can assure you, I know people who’ve been to loads of exhibitions who are completely fucking thick.” All the co-creators were treated like patrons of the arts. Which they were. Their jewelry was lent for the duration of the show, then returned to them at the end of it.

Which could be the end of our tale. Except that, for us, a key part of telling these stories was that they be heard by as many people as possible; that these intimate family-histories of migration, hope and upheaval keep moving, keep travelling outwards. They are stories that are very much Made in Marseille – but for us they talk about a human experience that resonates far beyond the city… Lazare is the French for Lazarus, the biblical returnee who’s said to have come to Marseille with Mary Magdalene and become the city’s first bishop – not bad for a zombie migrant. We always hoped that these precious stories, so nearly lost to the flames of the gold merchants’ foundry, would live again — and travel onwards. A book which brings together all the cyanotypes, jewels and stories (including two previously unheard testimonies unearthed as a result of the exhibition) was published late 2020. We give it away for free — asking that people pass it on and/or contribute what they feel its value might be to a charity of their choosing. A PDF version of the book (in English and French) can be downloaded here. The pictures tell you a certain amount — and give you a reasonable idea how much gold bullion you can buy with ten thousand euros (not so much it turns out… but still a lot to most of us). But it’s the words that have the real value. We hope you enjoy them, think about them, act on them, share them.