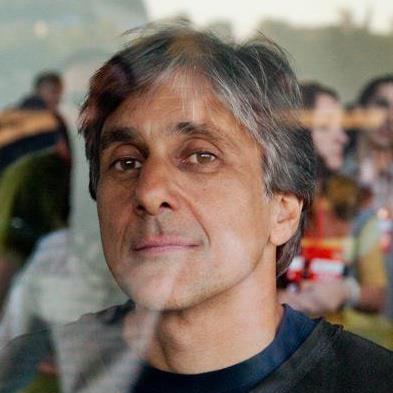

Writer-photographer Ara Oshagan mediates on the borders between North and South Korea and the blockaded enclave of Artsakh.

This essay is accompanied by three other stories, from Seta Kabranian-Melkonian, Mischa Geracoulis and Mireille Rebeiz, leading up to the annual remembrance of the Armenian Genocide, on April 24th.

Artsakh has been colonized and decolonized countless times. But for the past thousand years, since the fall of Ani in 1064 to the Seljuk Turks, Artsakh and the Armenian highlands have been under the grip of settler-colonizers who, over time, have become increasingly more violent. Artsakh in the 20th century reads like a Shakespearean tragedy.

Perceptions can falter at the demilitarized zone (DMZ) in Gimpo, South Korea. Double fortified military fences stretch all the way to the horizon and tower over you —menacing, seemingly impenetrable even though transparent. Fortified concrete bunkers are nearby and guards with military-grade weapons are at the ready, just beyond your periphery.

Beyond this fence is the verdant natural estuary of the Han River, easing, ebbing, flowing. It is stunning, deeply colorful, and layered with moving sediment. The thin band of water massages the floor of the estuary, creating a staccato chorus to accompany the racket of waterfowl. It’s a deep whooshing sound, vaguely guttural. It is as if the river is talking to you in an obscure foreign language.

Beyond the estuary, on the other side, is North Korea. The landscape you ponder, the geography across this lush expanse and across an abyss of ideology, is not any different than the one you are standing on. You imagine someone on the opposite side, standing and watching you in an identical posture. You feel as if a certain forbidden dialogue can happen at the border here, where the two Koreas try to connect.

It is hard to envision a border separating the two Koreas, even though it is very much there, more palpable than a wall. All borders are fictive — omnipresent across maps and sometimes part of our consciousness, but impossible to pin down, at once unavoidable and fleeting. They are drawn in the chimeric constructions of history and man, almost always in the chaotic aftermath of war. One day nothing is there and the next an impenetrable wall and armed soldiers guarding it. Or the exact opposite: fortifications and trenches that have existed for generations disappear overnight. Nowhere do you get that sense more than here in Gimpo, at a border that has divided a country and a people who share a language, a history, and a culture. Nowhere else do you see less the need for a border. And nowhere else is the border more fortified and divisive.

A divided country is not a country. It is a country in limbo, in perpetual wait. And a border is not a border like a country is not a country. What does it mean to have a border inside your country? To not be able to even see or cross to the other half? You are disallowed a relationship with your own country, disallowed a relationship with yourself. A border dividing a country divides you from yourself. It creates an identity crisis. One half looking for the other. An incomplete being. A split country is not a country.

The border at the Han River estuary at Gimpo was shaped and reshaped by a history of war and upheaval. A space of contention for centuries, Gimpo first appears in history in 475 AD. Named and renamed, conquered, reconquered, and freed multiple times, it is the famed site of the repulsion of the French in 1866. Japanese imperial occupation in Gimpo began in 1910. The airfield, now the Gimpo International Airport, was built by the Japanese who used Koreans to haul rocks from quarries 10 miles away. After the defeat of Japan and the end of colonization in 1945, the Korean peninsula was summarily split roughly along the 38th parallel by the two occupying armies — the South came under the command of the United States and the North under the Soviet Union. Korea slipped into the shifting sands and battle lines of the Cold War.

At the northern tip of South Korea, Gimpo was the first point of contact of the Korean War in 1950 when North Korea invaded the South. Gimpo airport was attacked within hours of the start of the war, with several military air transport planes destroyed. Three days later, Gimpo was captured. In the subsequent weeks, US and South Korea airstrikes targeted enemy positions in Gimpo and its airfield. In the fall of 1950, after the US landing on Inchon, Gimpo was back in US and South Korean hands. A few short months later, in January of 1951, Gimpo was overrun by Chinese forces supporting the North. A month later, it was back under South Korean control. For three years, retreating armies destroyed everything they could and advancing armies bombed everything they could. By the end of this grisly war in 1953, over 1 million South Korean civilians had died.

The Korean War in Gimpo and across the current border ebbed and flowed like the river itself. The land, the river, the people, the whole ecosystem was ever-shifting, destroyed and replenished, and destroyed again. The sediments and soil of the Han River, the landscape, and the communities at the border are all witnesses to that war, and carry with them that embedded history. The villages near the border are now part of the Civilian Control Zone (CCZ), and their calmness belies their tumultuous history. They are monitored only slightly less than the border itself. And up until very recently, North Korean propaganda broadcasts were beamed across the DMZ to these villages. Some facilities in the CCZ have built concrete walls in front of their north-facing entrances to guard against surprise artillery attack.

Once a border, always a border.

In the final armistice of 1953 that ended the Korean War, the Han River estuary became part of the border itself, as part of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). In the agreement, this zone, the estuary north of Gimpo, was designated as neutral — a free zone for civilian maritime travel and commercial shipping. For military and political reasons, neither the North nor the South has complied with this agreement, and both sides have forged ahead to arm their borders with barbed wire and heavy weaponry. This is what we see today: a thin but heavily fortified membrane on either side of a space that has been untouched by man for nearly 70 years. It is an unintended pristine sanctuary rich in wildlife, pregnant with war.

Gimpo, a region which used to be surrounded on three sides by water, is now hemmed in by a perimeter of barbed wire. The Han River estuary cannot be approached. Its three ports stand unused and inaccessible; its fishermen do not fish; its residents do not wade into the water. Gimpo has lost its river, the life-source and healing power of water. Its sole connection to the world now is through the south, through the municipality of Seoul. Gimpo has lost its independence and resembles a being with only one lung — unable to take full, deep breaths and open its arms and connect to the world. Gimpo is faced with an identity crisis, compounded by the border and a divided country.

The border permeates all. But all borders are not created equal.

Just east of the current-day Armenian republic is the eastern edge of the Armenian highlands. Beyond those final fierce mountains, the flatlands of Azerbaijan begin, leading to the Caspian Sea and then to Turkmenistan and Afghanistan beyond. Perched on that eastern edge is the indigenous Armenian region of Nagorno-Karabakh, or Artsakh to Armenians. Its cliffs are vertical, its forests lush, and its mountainscapes stunning. At the edge of the cliffs of Jdrdouz in Shushi, you are left breathless and feel as if you are at the edge of the planet: here land runs out and outer space begins.

Within this rectilinear landscape, indigenous Armenians have lived for millennia. According to Greek historian Strabo, the Armenians populated these loamy lands at least since the 2nd century BC. And foreign invaders have come and gone for just as long. Artsakh has been colonized and decolonized countless times. But for the past thousand years, since the fall of Ani in 1064 to the Seljuk Turks, Artsakh and the Armenian highlands have been under the grip of settler-colonizers who, over time, have become increasingly more violent. Artsakh in the 20th century reads like a Shakespearean tragedy.

After the First World War, with the formation of the Soviet Union in the early 1920s, the Bolsheviks effectively enabled Azerbaijan to colonize a region which had a 94% Armenian indigenous population. In the ensuing decades, Armenian language, culture, art, and history were severely suppressed, and in some regions nearly erased completely — not unlike what had happened in Korea at the hands of the Japanese. The Armenians of the region never ceased to demand autonomy or integration with Armenia from the Soviet authorities — but to no avail. On paper, they enjoyed an autonomous status with distinct borders. In practice, they were ethnically cleansed in a number of towns, such as in Shushi in March of 1920; the violent Azerbaijani response altered that town’s demographic composition from an Armenian majority to an Azeri one. In 1923, the Soviet Union turned Artsakh, or Nagorno-Karabakh, into an autonomous Oblast within the Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan, which was adjacent to the Soviet Socialist Republic of Armenia.

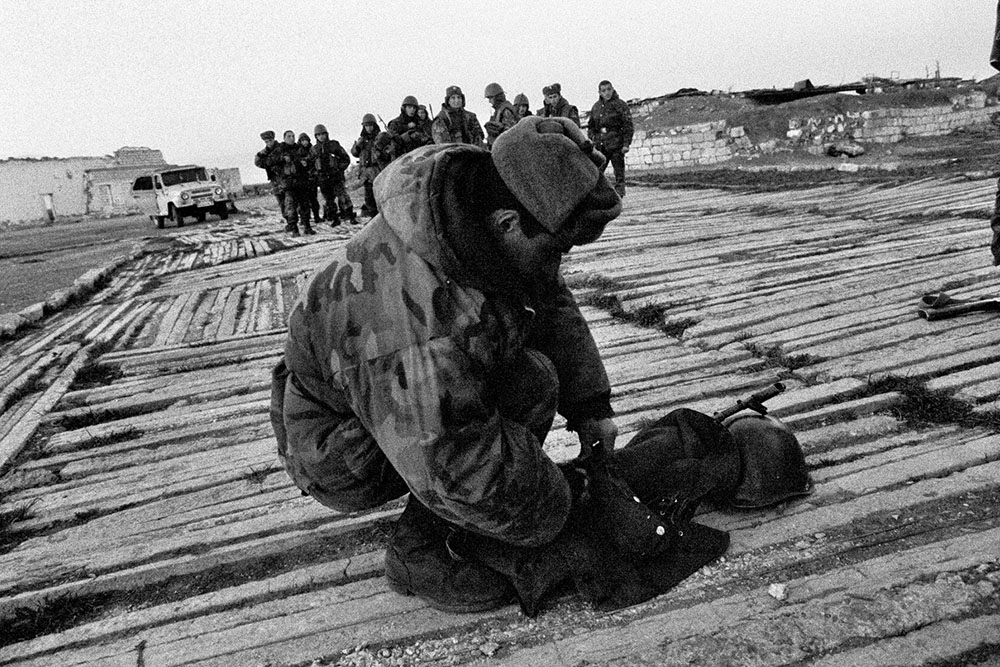

In 1988, with the impending collapse of the Soviet Union, the majority Armenians of Artsakh voted to secede from the union and proclaimed independence. The Azerbaijani response was simple: a repeat of the violence seen in Shushi. Extremist groups started to attack Armenian civilians living in Azerbaijan. First was the Armenian neighborhood of Sumgait — the third largest city in Azerbaijan. For three days, Armenians were beaten, raped, and killed in the streets and in their homes, as local police stood nearby. A similar massacre followed in the town of Ganja, the second largest city, and then a large-scale slaughter took place in Azerbaijan’s capital city of Baku. Particularly violent, with reports of dismemberment and Armenians burned alive, this slaughter and riot lasted seven days. It stopped only when Soviet troops entered the city and violently imposed order. In Artsakh and in Armenia proper, Armenian militias responded by expelling large numbers of Azeri civilians and in some cases resorting to retaliatory killings.

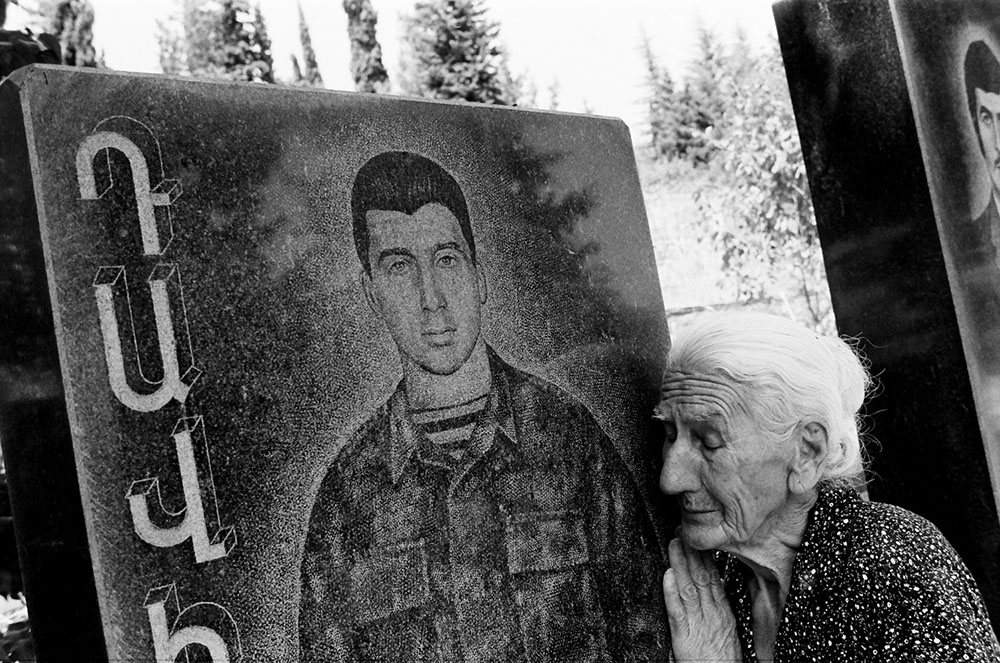

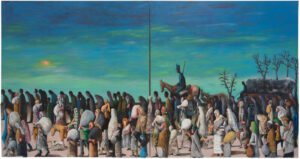

Against this backdrop of extreme violence, full-scale war between Azerbaijan and the Armenians of Artsakh erupted. Backed by a newly independent Armenia, the Armenians beat back and ousted a much larger and better-equipped Azerbaijani army and decolonized their land. The Armenians and Azeris both paid a high price — estimated 30,000 dead — via warfare, ethnic cleansing, and outright massacres by both sides. Civilians were expelled from their homes: 300,000-500,000 Armenians and nearly 800,000 Azeris, creating a massive refugee problem that is still largely unresolved. Nagorno Karbakh was left without any Azeri residents and a plethora of ghost towns and villages. But the Armenians triumphed on the battlefield, restored their country to a state of wholeness, and reaffirmed their identity. They shook off 70 years of erasure, set up a border, and dug trenches to defend themselves.

Over the next 30 years, the indigenous Armenians of Artsakh held free elections, elected presidents and parliamentarians, and established a complete government infrastructure — replete with a country emblem, a diplomatic corps, and a military. A democratic country by any measure. And they rebuilt their war-torn land, brick by brick. Difficult economic conditions hampered progress. And the geopolitics of the region was such that no other nation would recognize them as a nation. The international community, pushed by Turkey, Israel, and the US, insisted on recognizing the pre-1992 borders, which placed Artsakh inside Azerbaijan. Artsakh did not appear on any map as a country — it was merely a region inside Azerbaijan. A de facto, but not de jure, country.

Not unlike Gimpo, Artsakh also had a militarized and fortified border: an eight-foot deep trench running all the way around the country. A territory hemmed in on three sides by this border: its only view of the world through Armenia via a narrow strip of land called the Lachin corridor. For 30 years, this border stood as physical demarcation on the landscape, a scar, a trench, and fortifications to keep the Azerbaijani army out, a safeguard against re-colonization. An impenetrable border by most measures. But at the same time, it was not a border at all, as it was unrecognized by any other nation, even by Armenia. On world maps and international negotiating tables, Artsakh had no borders — period. Despite several peace efforts by the Organization of Security of Co-operation in Europe Minsk Group, Artsakh was never allowed a seat at the negotiating table. Artsakh had a physical border, but not a political one. Artsakh was a country that was not a country.

In September 2020, Azerbaijan attacked Artsakh. It overran its borders in six short weeks and re-colonized large parts of Artsakh itself. What had been there, fortified, built up for over 30 years, was gone overnight. Like a chimera. Like fiction. Could the line of demarcation that encircled Artsakh even be called a border? What do you call something so precarious and brittle that it can be swept aside with such minimal effort? Didn’t the Armenians realize the border they had created was not a border at all? Over the span of 30 years of independence, a national amnesia had set in regarding what this line of demarcation around Artsakh represented. The fragility of the border had become muddled and lost. For 30 short years, Armenians had imagined a future for themselves. They had imagined a reversal of a nearly 1,000-year history of loss, erasure, and colonization. Armenians had imagined a border and a possibility.

Korean and Armenian borders and political realities have certain parallels and abiding similarities. Both societies have lived through the indignities of oppressive colonization. Both peoples have seen the extreme violence of war for multiple generations — destruction and rebuilding and destruction again. The memories of these traumas persist today. Both nations are now split: Korea between North and South, Armenia/Artsakh between homeland and diaspora. One arising from the Korea War, the other from the Armenian Genocide and subsequent wars for nearly 100 years. Both nations still face concerted attempts at erasure of heinous past crimes against them by their colonizers. The Turkish state still denies the Armenian Genocide ever happened. And the Japanese government denies it had any culpability for the “Comfort Women” system of sex slavery during WWII. These denials are still happening now, 70 and 100 years later.

Borders — militarized, chimeral, invisible, imagined, uncrossable — are part of the very fabric of these nations. Armenians and Koreans carry their border with them.

In 2007, I was at the border in Artsakh, in a bunker on the front lines. Through a slit in the heavily fortified bunker wall, you could see the flatlands leading to the adversary’s positions. In terms of geography, the ground that stretched to the other border was not unlike the border in Gimpo. The level river expanse covers more or less a similar space, a flatness extending from your feet outward. I met a young man, an Artsakh soldier, in that bunker. He was at the ready, rifle in hand, with a shy uncertain smile masked by innate self-assurance. Yes, his eyes said, I am here, I have a weapon, but I have no idea if this is an actual border, or if the enemy will attack in five minutes or five years or five decades. But I am here.

I now wonder where this young man (who is no longer young) is today. Was he still in the military during the 2020 invasion, 13 years later? Did he imagine a future in this country that is not a country? Did he imagine a time when that flatland could become a space of cooperation and understanding, shared by the two nations? Did he dream of a time when Armenians and Azerbaijanis could live peacefully among each other?

In a similar dream, one can perhaps see the Han River Estuary also as a space of sharing: crossed by North Koreans traveling south and Southerners traveling north. Can borders be spaces of cooperation and sharing, rather than division and conflict? Can the verdant and harmonious natural habitat of the DMZ be a model of human harmony? One can imagine the deeply colorful and layered geography of the Han River estuary without barbed wire fences or heavy military fortification on either side. One can imagine Gimpo breathing again and its ships shuttling between its ports. One can perhaps imagine Korea restored to itself and Artsakh decolonized once again.