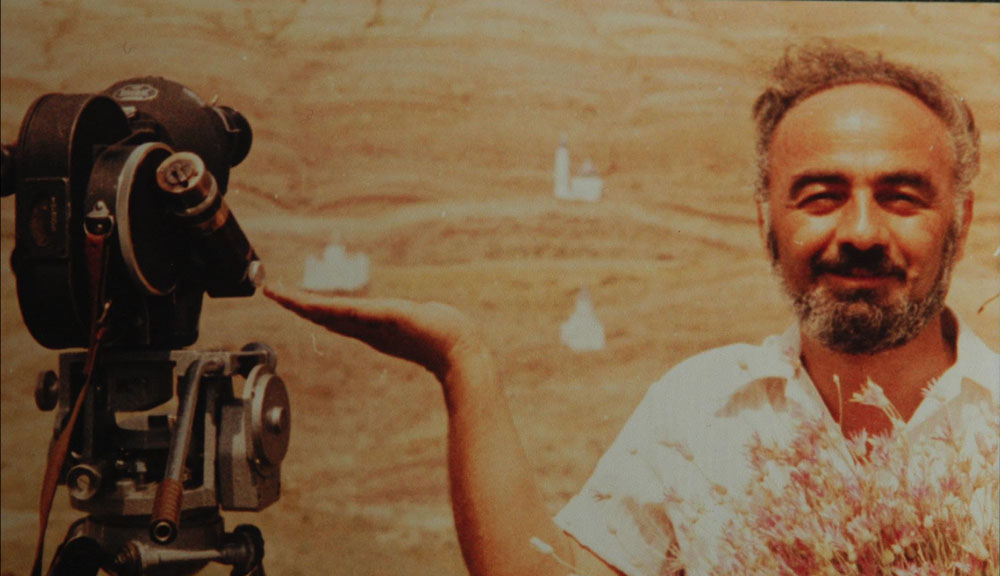

Sergei Parajanov, revered as one of the most innovative directors in cinema history, was significant for his willingness and capacity to blend European and Middle Eastern traditions, tales and vernacular art.

William Gourlay

January 2024 marks the centenary of the birth of Armenian filmmaker Sergei Parajanov, revered as one of the most innovative directors in cinema history. Working for the USSR State Committee for Cinematography, Parajanov created a body of work that has been praised by cinema figures from Francis Ford Coppola to Martin Scorsese and Jean-Luc Godard. His influence can be seen across the visual arts in the movies of Mohsen Makhmalbaf and Lady Gaga and REM music videos.

In a series of movies from 1965’s Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors to 1988’s Ashik Kerib, Parajanov developed his own distinctive cinematic idiom. He experimented with color, sound and filmmaking technique, using jump-cut editing, overdubs, face-to-camera shots and “tableaux” — still images of objects laden with symbolism — to create a quasi-archaic style, building the momentum of his films through painterly metaphor rather than linear narrative. Under Parajanov’s direction characters acted with pantomime affectations in intricately wrought sets awash with allegorical motifs and carnivalesque color.

Parajanov’s major works were interpretations of myths and legends from the fringes of Europe, the Caucasus and Carpathian Mountains. The British Film Institute described his films as “transforming… folklore into visual poetry.” James Steffen, in his masterly examination of Parajanov and his work, remarked that his main accomplishment was to introduce global cinema audiences during the Cold War to non-Russian cultures including Ukrainian, Armenian and Azerbaijani.

Parajanov was also significant for his willingness and capacity to blend European and Middle Eastern traditions, tales and vernacular art. A cultural magpie, he drew inspiration from across religious, ethnic and linguistic boundaries — from Orthodox manuscripts to Persian miniatures, from Georgian legends to Turkish fairy tales. Parajanov once praised the Kurdish director Yilmaz Güney for creating works that “straddle[s]… the Orient and the Western world.” Parajanov himself exemplified this, his cinematic oeuvre documenting the rich artistic overlap between the “West” and the “Orient” and elements of cultural heritage that belonged to both worlds.

Perhaps such an approach to the creative process should not be unexpected given that Parajanov was born an Armenian in Tbilisi, Georgia, in the heart of the Caucasus mountains. In the 1840s, the German traveller Baron Augustus Von Haxthausen wrote, “In Tiflis [Tbilisi], Europe and Asia may be said to meet.” Long the seat of Georgian monarchs, Tbilisi has also been ruled by Arab emirs, Turks, Persians and Soviet commissars. More broadly, the Caucasus region has for millennia been a place of cultural interactions between peoples. Traversing the Caucasus, Von Haxthausen noted “[Muslim] Tatars, Circassians, and Persians, and…Christian Georgians and Armenians, inhabit the same villages…and sometimes even eat together on the same carpet.”

As James Steffen records, Parajanov grew up in the cosmopolitan atmosphere of Old Tbilisi, familiar with the folk art of Niko Pirosmani and the traditions of ashiks (ashugh in Armenian), the multilingual poet-minstrels of the Caucasus. Parajanov’s initial inclinations were musical. Enrolling at the Tbilisi State Conservatory, he proved a talented singer and violinist, but in 1945 he won a place at the State Institute of Cinematography in Moscow, and followed a new artistic path. In 1951 he produced his graduation movie, A Moldovan Fairytale, based on a short story. In a later essay for the Russian film studies magazine Iskusstvo Kino, he remarked, “The poetics of this work came to me almost at once… I was attempting to build an expressive system originating directly from folk poetry and mythology.”

Several feature films including a reworking of A Moldovan Fairytale followed, during which Parajanov refined his craft in Ukraine, without achieving a major box office hit or winning critical acclaim. Seeing Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1962 dream-like, anti-war feature Ivan’s Childhood, however, was a watershed experience for Parajanov. He allegedly disowned all of his earlier output and embarked on a new creative trajectory.

His next feature was his breakout moment. Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, a tale set among the Hutsul people of the Carpathians, based on a short-story by Ukrainian writer, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, attracted worldwide attention, winning awards at festivals across Europe and North America, and enjoying an extended run in French cinemas. It was while creating Shadows that Parajanov forged the signature style that was to define his subsequent works. This approach, described by Steffen as “poetic cinema,” involved innovative use of sound, music and voiceovers, and the recurring positioning of objects — handcrafts, textiles, ornaments, artisanal tools — as “symbolic motifs to provide an overarching thematic structure.”

Local and international acclaim, however, did not ensure a comfortable future or ongoing success for Parajanov. Political circumstances got in the way. During his time in Ukraine, he had associated with dissidents, which, in combination with his departure from the prescribed Socialist Realism creative doctrine, his outspokenness and propensity for challenging prevailing hierarchies, saw him fall foul of Soviet authorities. His ongoing projects in Ukraine, including the never-finished Kyiv Frescoes, were blacklisted and he left Kyiv for Yerevan.

After moving to the Armenian capital, Parajanov created The Color of Pomegranates. Many regard this as his masterpiece. Theoretically, the film offers an account of the life of the fabled 18th century Armenian bard, Sayat Nova, but a direct narrative is difficult to discern as the viewer is gifted with a flood of symbolic images and scenarios. Upon seeing the film Martin Scorsese remarked, “I didn’t know any more about Sayat Nova at the end of the picture than I knew at the beginning”; nonetheless he declared it a “timeless cinematic experience.”

Ahead of the film’s release, Parajanov stated, “We want to show the world in which the ashugh [Sayat Nova] lived, the sources that nourished his poetry… National architecture, folk art, nature, daily life, and music will play a large role in the film’s pictorial decisions.” The shoot was completed in the Armenian monasteries of Haghpat and Sanahin, in Georgia’s Kahketi region and the Azerbaijani capital of Baku. Levon Gregorian, assistant director on set, observed that it was Parajanov’s intention to “reveal the culture of the three peoples of Transcaucasia.” The figure of Sayat Nova provided a perfect medium for such an endeavor. He was the most celebrated of the ashugh, a tradition that was common to Armenians, Georgians and Azerbaijanis. Indeed, Sayat Nova’s canon includes poetic works in Armenian, Azerbaijani, Georgian and Russian (and, according to some scholars, Persian).

The ashugh tradition was heavily influenced by cultural currents that entered the Caucasus from the Islamic world. The name itself is derived from the Arabic term ashiq (“lover”), although it was Persian poetic conventions and musical ideas in particular that informed the arts of the minstrels. Persian influences are also immediately apparent in The Color of Pomegranates. There are frequent shots of Qajar-era Persian frescoes, while central characters in certain scenes wear costumes from the same period. In a later interview, Parajanov remarked that he intended the movie to resemble a “Persian jewelry case. On the outside its beauty fills the eyes; you see the fine miniatures. Then you open it, and inside you see still more Persian accessories.”

Despite the acclaim that The Color of Pomegranates received, Soviet authorities continued to regard Parajanov with suspicion. In 1974 he was sentenced and imprisoned in Ukraine on politically motivated charges. An international campaign for his release saw him win his freedom in 1978, but he was imprisoned again on bribery charges in 1982. During this period, he managed to sustain his artistic output, creating a series of collages and sketches that are now housed in the Sergei Parajanov Museum in Yerevan, Armenia.

On his release from prison, Parajanov bounced back promptly. His next feature, The Legend of Suram Fortress, first screened in 1985, was based on a long-standing Georgian folk tale about a youth entombed in the wall of a castle to fortify its structure. Like The Color of Pomegranates, created over 15 years earlier, the new release was liberally endowed with Turkish and Persian motifs and symbols, both active, such as a muezzin performing the call to prayer in Arabic and bazaar-goers exclaiming in Azerbajiani, and passive, such as now-familiar “tableaux” shots that featured hookah pipes, Turkish porcelain bowls and copperware. There were also innovations, including a more clearly discernible story line and broader framing of some scenes using widescreen landscape shots. Parajanov shot in locations in Georgia as well as the Palace of the Shirvanshahs in Baku, again bringing a trans-Caucasian aspect to the movie. James Steffen notes that alongside Parajanov’s use of Turkish and Persian imagery, he also emphasises “Georgian visual motifs,” in so doing evoking “a Georgia that possesses a distinct cultural identity but is nonetheless permeated with Persian and Turkish cultural influences.”

This movie, too, won international awards, including the prize for the Most Innovative Film at the Rotterdam Film Festival in 1987, which Parajanov was able to attend. Indeed, in the era of emerging perestroika in the Soviet Union, he was able, for the first time since the early 1960s, to proceed to his next project without official censure or harassment.

Sure enough, in 1988 he produced Ashik Kerib, which was to be his final complete feature. Here, again, he drew on Caucasian folklore, and, again, his creative vision emerged from cross-cultural seeds. Parajanov recounted that when he was ill as a child in Tbilisi, his mother related the story of Ashik Kerib, a much-loved Turkish fairy tale that had been retold by Russian author Mikhail Lermontov. Ashik Kerib is a penniless, Muslim ashik from Tbilisi, who is denied the hand of his beloved and takes to the road to make his fortune in order to win her back. As film critic Laleen Jayamanne explains, Parajanov uses this tale, and the tribulations that Ashik Kerib encounters, to examine Sufi Islam, which has had a pervasive impact across the Caucasus. The roaming ashik “does not know what he will encounter,” Jayamanne notes, as he follows a path that “does not previously exist, but is created with each step,” thereby creating “the Sufi way.”

Russian folklorist Mark Azadovskii noted that Lermontov’s story, which inspired Parajanov, is laced with Turkic, Arabic and Persian terms, as well as Georgian and Armenian places and names, and thus is an example of the “cultural interpenetration” of the Caucasus. There are numerous examples of this in Parajanov’s movie. Persian influences are apparent everywhere, from costume design to the use of Persian miniatures in signature “tableaux” scenes, dialogue is in Azerbaijani, the soundtrack juxtaposes church choirs with Azerbaijani mugham music and while most of the movie was shot on location in Azerbaijan, initial scenes were staged in a wooden mosque from Georgia’s Adjara region.

Once again, Parajanov was lauded for his ebullient creative vision, winning awards internationally, including the Jury Special Prize at the Istanbul Film Festival in 1989, where he travelled to engage with cinema goers. Yet, again, Parajanov’s creative triumph was undermined by political circumstances, this time on a wider scale. Escalating conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis from 1988 delayed the distribution of Ashik Kerib in Armenia. According to Steffen, Parajanov had great affection for the Azerbaijani capital, Baku, and he felt intense sorrow at the violence that erupted between the two peoples. Over 30 years later, ongoing tensions and nationalist acrimony between the two Caucasian states mean that there is no way that a movie such as Ashik Kerib could be shot on location by an Armenian production team.

Meanwhile, Parajanov moved on to his next projects, an autobiographical film, The Confession, and a screenplay titled The Treasures of Mount Ararat. Both remain unrealized, as Parajanov was hospitalized with lung cancer in Yerevan, dying at the age of 66 in July 1990. He was widely mourned in his home city of Tbilisi and across Armenia, and by cinephiles globally, a group of Italian directors, including Federico Fellini, declaring, “Cinema has lost one of its magicians.”

In terms of number of feature films produced, Parajanov’s output was relatively modest but his dazzling imagery and unbounded imagination have had an enduring impact, winning hearts and minds and bewitching cinemagoers worldwide. His legacy lives on in his museum, inaugurated in Yerevan, Armenia, in 1991, and a recently unveiled statue. The affection that Georgia holds for him is apparent in the recent naming of a street in his honor in Tbilisi.

In 2023, UNESCO voted to recognize the 100th anniversary of his birth. Indicative of affection for him across Europe, the UNESCO application was jointly submitted by Armenia, Georgia and Ukraine, and was supported by Cyprus, France, Italy, Lebanon and Poland.

Ultimately, Parajanov was an auteur with a distinctive vision who created jewelled cinematic moments from objects, legends and rituals from across Europe, the Caucasus and Western Asia. We are left to imagine what else he may have created had he not been hobbled by the strictures of the Soviet regime and had his life not been cut short by illness.