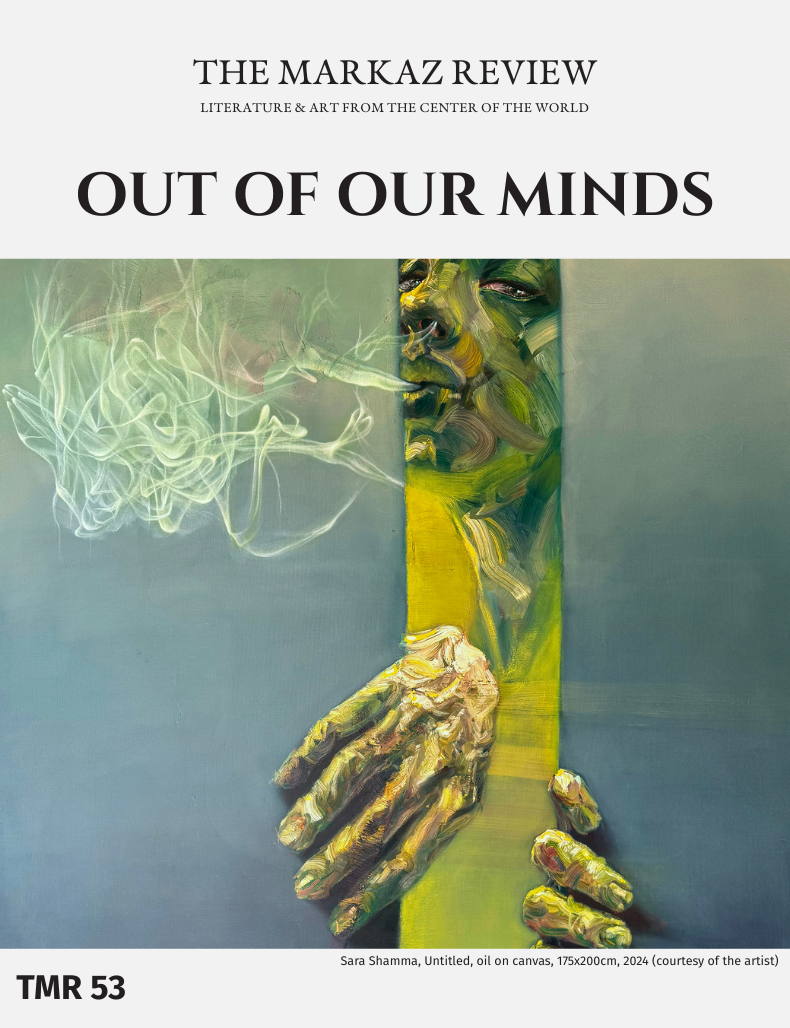

As more countries turn rogue and the mental health of populations are affected, salutary lessons come from Iran. Depression there is at an all time high and in the aftermath of the Women Life Freedom protests some people feel a sense of hopelessness. Iranian doctors, psychotherapists, and human rights advocates in exile explore new horizons in talk therapy and combat despair in lives blighted by authoritarianism.

Trust and rapport are the basis of strong therapeutic relationships. But what if a therapist sees clients through video sessions or faceless phone calls thousands of miles away, in Iran? Can talk therapy to address issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder, heightened levels of anxiety, or debilitating depression be beneficial from this far away?

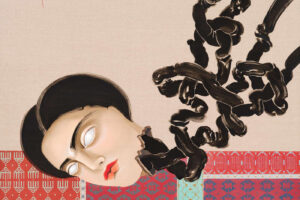

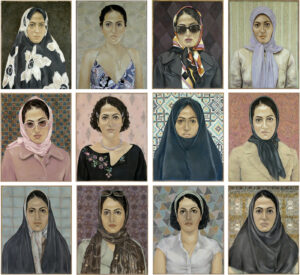

The narrative of the Woman Life Freedom (WLF) movement was mainly triumphant. The 2022–2023 nationwide protests changed global perceptions and gave new visibility to a young generation of Iranian women who challenged a draconian and violent Islamic republic. Yet, for many still living in the country or forced into exile because of their political activities, scenes of cosplaying Hollywood actresses cutting their hair in solidarity seem a lifetime ago.

Now in the streets of Tehran and Iran’s smaller cities, women regularly appear in public sans headscarves. Sporadically the government reacts, with arrests by black chador-clad female morality police; phone calls threatening taxi drivers with the confiscation of their vehicles for ferrying veil-less passengers; and the banning of women not wearing headscarves in banks or public offices. Still, life in the Islamic Republic sputters along under never ending US economic sanctions and periodic Israeli threats.

For each inch of public space hard-won by the WLF movement, darkness persists for many. Demonstrators wounded in the eye or shot 100 times by the security services with a BB gun, sometimes in the groin, live with their disabilities. Some protestors released from prison have returned to antagonistic patriarchal and religious households. Then there are those without any visible injuries who feel like the walking dead. They suffer from lasting psychological effects of the failed promise of the woman-led movement, which brought out on the streets thousands who dared to hope for a radically different national life.

Since the pandemic, the numbers of people in therapy have skyrocketed. Is therapy of any real use to people in totalitarian states?

This is the story of Iranians who care.

Psychotherapists Shirin Amani Azari and Shahrzad Pourabdollah left Iran after the 1979 Islamic revolution and still feel a deep affinity with the Persian people and culture. As well, Dr. Kamiar Alaei and Dr. Arash Alaei were imprisoned in Iran after working with HIV patients. In exile in the US they founded Mahsa (Medical Alliance for Health Services Abroad) during the height of the WLF protests; and provide emergency mental and physical healthcare to wounded demonstrators and activists inside their country. Still others, like the editor-in-chief of the IranWire news service, Maziar Bahari, believe that reporting news from Iran comes with a duty of care. Online systems of counseling and mental healthcare by overlapping networks of engaged health professionals and human rights activists provide a template for helping not just Iranians at risk from their government. Customized versions of this model could alleviate the suffering of people living under authoritarian rule anywhere.

Tale of two psychotherapists

Shirin Amani Azari specializes in PTSD and counsels WLF protestors over a smartphone app. People in Iran are wary of revealing their identities in case their families or, worse, the government find out. For that reason Azari doesn’t know the names of the people she speaks to. She never sees their faces nor do they see hers. Her sessions with individual clients last for one hour, once a week, and end after a year.

During our conversation over zoom, I ask how she as a therapist can bring people suffering from PTSD back to resilience, and themselves.

She counters in that extremely polite way that Iranians do when they disagree. “You’re looking at it from a point of view of someone losing something in the west. It’s not about bringing them back. It’s like walking with them through the journey, or working with someone who’s in a war zone and doesn’t know when the war will end.”

She volunteers for Mahsa Medical and works with clients who “see the country as a prison. It’s not as if they say, ‘Oh, I’m not happy in this country, and I have an opportunity to leave if I want to.’ It’s more like: ‘I don’t have the option of doing anything else, and I’m imprisoned in my own family home.’ Many of them came home from prison and were beaten up by their dad or brother for having voiced their objections” to the Iranian regime.

Instead, Azari focuses on “coping mechanisms”: how people feel; how they can regulate their emotions; and how they can utilize skills and strategies that might be helpful to them, such as during panic attacks. She characterizes her work as “having someone follow or shadow you on that journey to see how it evolves. They can trust that this is a safe space, which is basic in the therapeutic world.”

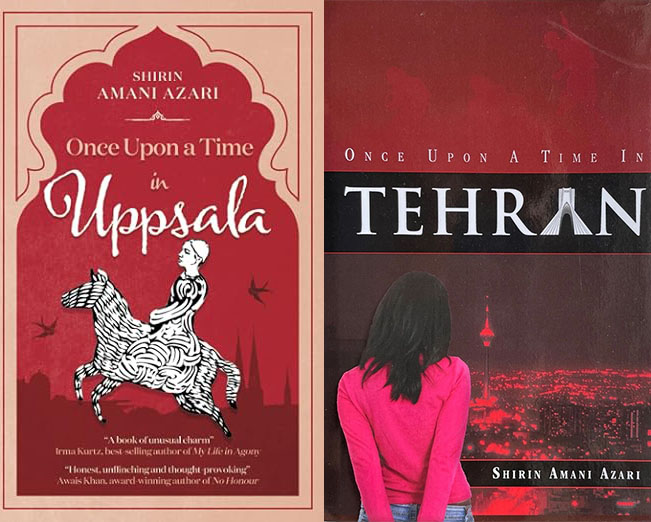

Azari was born in Iran. When she was 11, her family moved to Sweden during the Iran–Iraq war in the 1980s, stories she recounts in Once Upon a Time in Tehran and Once Upon a Time in Uppsala. Today Azari works in one of London’s most deprived boroughs as a supervisor at Docklands Outreach, a preventative National Health Service support agency for children, teenagers, and young adults. In 2022 she had been attending WLF protests in London and Berlin with a friend who told her about the work of Mahsa Medical.

Azari keeps a dedicated telephone line for her Iranian clientele and their therapy. Because she never sees their faces, the human voice is telling. She reveals, “There’s so much going on that we underestimate because we’re so used to seeing. The rhythm of someone’s voice can slow down. They feel you are aware of the shift and notice that you are present with them.”

What does she do when people overwhelmed by emotion stop speaking?

“In the silences a process is happening. It’s ongoing, moving, and towards the end of the silences, there is a shift. As a therapist you’re not supposed to break that silence so that the shift can happen, because otherwise you’re taking control, you’re taking the lead, which you’re not supposed to do.”

One of Mahsa Medical’s founders, Dr. Kamiar Alaei, once told her that at the start of therapy, he noticed that many clients didn’t include a picture of themselves on their smartphone app. Then after six months a photo — perhaps not showing their faces — had suddenly been added. Azari sees this same trend among the Iranians she counsels: after months of working together, a picture of a bird or a sun appears on their account. She says that’s when she thought, “Oh my God, I cannot imagine anything more rewarding that this.”

The internet has provided many more opportunities for advice on mental health issues that were previously not recognized and have become talking points the world over. In July, Azari appeared on a live IranWire Instagram broadcast about ADHD for Persian parents. During the pandemic, counselor and psychotherapist Shahrzad Pourabdollah was regularly interviewed by Iranian journalist Aida Ghajar for IranWire, again live on Instagram, and fielded questions from members of religious minorities, journalists, and prisoners.

Shahrzad Pourabdollah, who specializes in families, couples and individuals, also treats Iranians on a one-to-one basis through an initiative sponsored by IranWire. She lived in Iran until she was 21 and moved to Belgium for 22 years before relocating to London. In 2011, she had been initially skeptical about posting videos on YouTube, about mental health issues in Farsi, but went ahead. Soon after increasing numbers of Persian-speaking clients, initially from Canada and US, contacted her and requested online therapy. This was well in advance of the massive change the field underwent as it moved from face-to-face encounters to online sessions during the pandemic. Unlike Azari, being able to see her clients is essential for Pourabdollah. “I don’t accept a phone call. It has to be a video call because body language is important,” she says.

Some of those she counsels for IranWire include journalists or people in media who have experienced imprisonment and torture. During the WLF protests, both female and male demonstrators and activists, some with eye injuries, came to her for online therapy. Most of them were under 30 or 40. Some were in Iran or they had been forced to flee to Turkey or Erbil, in Iraqi Kurdistan. Others were newly arrived in Germany.

During our Zoom conversation, she recalls, “They were still in shock. They couldn’t talk. They were frozen. Just a few months later they had just started to realize what had really happened to them.”

The logistics of giving therapy to Iranians, at home, challenge long-held western therapeutic practices, which insist that in order to work effectively with traumatized people you need to provide them with a sense of safety.

Pourabdollah is pragmatic. “This is a luxury,” she states. “You’re talking about Iranians still in Iran. We cannot get them out. I have to find a way of working with them. You’re dealing with a situation that’s not going to budge. To enjoy a mental balance you need a sense of safety, security, and certainty. In Iran, there’s no certainty; people lost this sense a long time ago.”

Pourabdollah: To enjoy a mental balance you need a sense of safety, security, and certainty. In Iran, there’s no certainty; people lost this sense a long time ago.

New definition for PTSD

The fraught political situation inside Iran, or the onslaught currently taking place in Gaza, has called for a reassessment of PTSD, which some practitioners in the global South believe has an inbuilt western lens or bias. Palestinian psychiatrist and psychotherapist Dr. Samah Jabr has written in the Guardian, “Trauma in Palestine is collective and continuous. PTSD is when your mind is stuck in a traumatic loop. In Palestine, the loop is reality. The threat is still there. Hypervigilance, avoidance — these symptoms of PTSD are unhelpful to the soldier who went home, but for Palestinians, they can save your life. We see this more as ‘chronic’ traumatic stress disorder.”

Iranians at home may not yet live in a war zone but the levels of surveillance and fear of arrest and imprisonment no doubt contribute to, for some, a permanent state of hyper-arousal.

The therapy Pourabdollah gives through IranWire differs in another way from her practice with her private clients. Usually the decision to end their sessions is mutually agreed by psychotherapist and client. The therapy she does through the auspices of IranWire comes with a time limit due to funding considerations.

“With [the IranWire] client, we know from the beginning it would be five sessions. The first would be a kind of assessment session; I always take a history, family background, otherwise you cannot be honest. We would try just to focus on the issue more than outside influences. It was really helpful because they were so lost.

“When you see someone traumatized, it’s like their internal clock is not ticking anymore, or is ticking slowly. Then I see how much five sessions would help them. I’m not telling them that they wouldn’t feel anxiety anymore, but they would know that what they are going through is normal.”

Recognition and acceptance hopefully means that someone can take steps, no matter how small, away from anguish and pain.

Depression in Iran

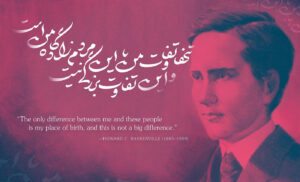

In their video interviews with me, both psychotherapists Pourabdollah and Azari spoke about the high levels of self-medication commonplace in Iran. In 2023, the reformist newspaper Ham-Mihan reported one in every five prescriptions issued in the country is for antidepressants or sleeping pills. A 2024 report by the Tehran Studies and Planning Center reveals 99.7 percent of Tehranis struggle with depression, and this has led to an increase in levels of migration, alcohol and substance abuse, and suicide. “Iranians have been affected psychologically for the past 45 years,” observes Maziar Bahari. He quotes the former mayor of Tehran Gholamhossein Karbaschi as saying they should add Prozac to Tehran’s water because people are so depressed.

Bahari and I have known each other for over a decade and coedited a book together. After his release from imprisonment and torture in Evin Prison in 2009, he returned to London and started IranWire in 2014, which works with “friends and colleagues” — who are citizen journalists, activists, and people inside Iran. They share news and information on the platform but also use the news and information, produced by professionals, in advocacy campaigns. He sees IranWire as having “a holistic approach … rather than just a media outlet. So we try to help people with their legal problems. We’ve had legal advice for the past ten years and psychosocial support for five years now, but it depends on the funding.”

In 2024 IranWire supported the study “The Psychological Health of Iranian Citizens Protesting the Actions of Their Country’s Morality Police,” by Sophia Marchetti and Anthony Feinstein, in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. It found that in the sample group of 63 WLF demonstrators interviewed inside the country by citizen journalists that people wounded in one eye or, in some cases, both eyes, “had less severe intrusion symptoms of PTSD … than the non-eye wound group.” These people had experienced a positive mental effect from protesting, although that might not necessarily be the case for the population at large.

“In general Iranians need psychosocial support,” says Bahari, “because there are issues in Iran in terms of economic problems [as well as] social issues, drug addiction, prostitution, poverty, homelessness, divorce, separations. So a journalist or an activist or a lawyer who works with us can be affected by any one of these. On top of that, they have to deal with censorship or [in some cases] losing their income when their newspaper shuts down. Or they have to deal with being in prison.”

He points out that the costs of therapy inside Iran constitute “a big chunk of your income,” while being realistic about the scope of his Iran-focused wire service. “We try to do as much as we can, and of course, we know the shortcomings, but this is a reality we deal with.”

In 2017, during a speech for World Health Day, Iran’s then health minister, Hassan Ghazizadeh, admitted, “In our country, girls suffer from depression more than men, and presently this mental disorder has multiplied by 50 percent.”

He blamed depression on widespread migration from the village to the city, changing lifestyles, and the “extreme psychological and spiritual damage” of poor living conditions on the outskirts of cities. He didn’t mention the discrimination against women and their lack of opportunity, underlining causes for the anti-hijab protests that were to rock the country five years later.

Academics, social scientists, and researchers inside Iran produce highly respected statistical-based psychiatric research. In the peer-reviewed journal Archives of Iranian Medicine published by Iranian Academy of Medical Sciences, the 2022 study “Major Depressive Disorder in Iran: Epidemiology, Health Care Provision, Utilization, and Challenges” by Masoumeh Amin-Esmaeili et al., concludes that “One in eight adults in Iran is estimated to have major depressive disorder (MDD) — a leading cause of disability in the country.” The study provides a detailed overview of the psychiatric services and education and levels of treatment available in the country, yet the root causes for MDD were not within the purview of the study.

Inside the country, criticism of the Islamic regime remains a red line. Bahari says, “Even among some pro-governmental institutions, they try to do good research. But the problem is that the government or the regime doesn’t listen. Or in some cases, they put them in jail because of their research and studies, if the government finds them too sensitive or if they get attention. I think after the 12-Day War with Israel, the government became even more sensitive because they think that people are helping the enemy by divulging such information.”

Maziar Bahari quotes the former mayor of Tehran Gholamhossein Karbaschi: they should add Prozac to Tehran’s water because people are so depressed.

A model for dictatorships

Drs. Kamiar and Arash Alaei experienced firsthand for themselves government blame, backlash, and subsequent imprisonment for health initiatives that the Iranian authorities disliked, found threatening or strengthened ties to foreign powers.

In 1997, the two started their first Triangular Clinic for people living with HIV AIDS, sexually transmitted diseases, and who injected drugs, in a storage room in their home city of Kermanshah. Dr. Kamiar recalls, “This was at a time that medical treatments were not available. We did the first study to see what the main cause of mortality is among people with HIV AIDs. In other countries it was opportunistic infections due to immune-compromised [conditions]. [In Iran] 58 percent committed suicide during the first year, which means they could have survived ten more years without medication. But they decided to terminate their lives due to social isolation, misbelief, and disinformation. This was when we realized that more than a fancy clinic they needed somebody to talk to them and, more importantly, to their families.”

The clinics were eventually set up in 67 cities and 57 prisons, and provided social care alongside clean needles and methadone. In 2003, the Triangular Clinic was awarded best practice model by the WHO. Three years later Dr. Kamiar participated in a US-Iran diplomacy health exchange program and brought US medical students to Iran. The methodology and practice of the Triangular clinics were copied in neighboring Afghanistan and Tajikistan.

Despite international acclaim, or perhaps because of it, in 2008 the doctors were tried in a one-day, secret trial for colluding with the US. Dr. Kamiar was sentenced for three years, and was released after two and a half years. For similar reasons his brother Dr. Arash, declared a prisoner of conscious by Amnesty International, was sentenced for six years. In 2011 Dr. Kamiar accepted the Jonathan Mann Award for Global Health and Human Rights on behalf of the brothers. Later that year Dr. Arash was pardoned by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei and released with 100 other prisoners for Ramadan.

Their experiences only hardened a lifelong commitment to humanitarian healthcare that entwines treatment for both the mind and the body. Dr. Arash describes how growing up in Kermanshah, a frontline city in the Iran–Iraq War, contributed to this approach. “We saw numbers of attacks by the Iraqi Army on our city and we were displaced for months during the war. So during war, conflict or even protests, the main and first reaction is a mental reaction, anxiety and stress.” He goes on to say that then after physical injury, mental trauma would manifest itself again later on.

They’ve worked on humanitarian healthcare projects during war, including opening a Center of Woman’s Heath for Yazidi women who were raped by ISIS, in Iraqi Kurdistan. From the US, with a network of students and faculty members, they provided long distance online medical lectures to internally displaced Syrian medical students during the Syrian war. The project laid the groundwork for the technology and the techniques the doctors would use for Mahsa Medical.

As Dr. Kamiar explains, “People who are internally displaced are more vulnerable compared to refugees because refugees receive support through UNHCR. But the lives of the internally displaced are in danger. They have to relocate every night. The first night we met virtually in the basement of a restaurant. The next day they had to move to another place but fortunately most of them had a smartphone, which was a good alternative. They could use a charger one hour a day.” The efficacy of the smartphone in Syria gave Mahsa Medical clinicians a flexibility they rely on today.

Out of the 23 countries in the Middle East, Syria is the only one where the medical terminology is taught not in English but Syrian Arabic. The Iraqi doctor whom the brothers had found to give anatomy lessons in Arabic to the Syrian students did not work.

“That was a good lesson for Iran,” nods Dr. Arash as the three of us converse over Zoom. He adds, “Even in Iran, the main language is Farsi. But that doesn’t mean that all the people from Sistan and Baluchestan to Kurdistan communicate well in Farsi. Because of that when we delivered service through Mahsa Medical, we have doctors from the Kurdistan region as well as Kurdish doctors living in Sweden. So we had that diversity to solve the language and communication barrier.” Perhaps one of the baseline breakthroughs of Mahsa and other initiatives has been the recognition of a multitude of identities through the languages people speak and understand.

Telehealth as resistance

During the first two weeks of the WLF protests, he says, “the challenge was that the government, army, and police were attacking people who protested. Those who were injured showed up in the hospitals; and at that time our action was document[ing] those who had been tortured. But later we received a message from our friend in the hospital who told us that the police were tracking patients, going to the hospitals, searching for them, and arresting them.”

This was the first time the authorities targeted both demonstrators and healthcare providers. Since hospitals were no longer safe, Mahsa began initiating treatment from afar. Some of the injured had online consultations with Mahsa doctors outside the country. Others who were badly injured went to clinics in private hospitals at specific times, where a supportive healthcare practitioner met and treated them. Again, neither protestor nor healthcare provider knew each other’s identity.

“There were a lot of security concerns,” admits Dr. Kamiar, “at the same time we told medical providers ‘Don’t provide any information about us in case there is a spy’” among those posing as patients. Others who were badly injured were told to immediately seek help at their nearest hospital, even if it meant risking arrest.

Mahsa Medical soon grew into a formidable network. According to Dr. Arash, “When we asked for volunteers, you wouldn’t believe how many healthcare providers we had: Iranian American, Iranian European, Iranian Australian, and different countries, from plastic surgery to orthopedic to child psychiatry to trauma.” WLF galvanized Iranians medical professionals in exile, like Azari and Pourabdollah, who are determined to help their people.

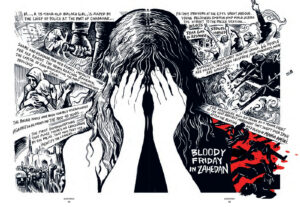

As the demonstrations continued, the numbers of patients using the clinic only increased. Dr. Arash remembers, “In Kermanshah there was a chemical attack on the community. In Zahedan, in Sistan and Baluchestan, it was a massive shooting and killing of people. In Tehran it was more eye injuries. In the eye group, we had 20 eye surgeons. For mental health we had different specialties.”

Despite Mahsa’s focus to not duplicate existing services, such high demand was increasingly difficult to meet. The Alaeis consulted the 225 doctors and healthcare providers working with them, and they developed training videos and brochures for additional support and posted them on social media. Dr. Arash stresses, “Even after the chemical attack on girls’ schools, [we thought] how can we provide services to the students and their families? Again, we had a series of videos, plus one-to-one consultations. When we look at the information we have nowadays, we see that the majority of our clients need mental compared to physical [treatment].

“One question is why does Iran have the highest rate of drug users, the highest rate of mental medication, and mental disorder medication? This is related to social depression. Yes, there is no hope. There is no good economical situation. There is no freedom, no public gatherings. Basic depression and anxiety are there. Now we have social anxiety because of the opinions and actions of the government.”

The problems of Iran appear monolithic yet Dr. Arash remains hopeful. “The key message is that we should do something to help others. The issue is bigger than our Mahsa network. We have a practical model. It works, and not just for Iran. There are numbers of dictatorships. Our model can help others see how you can do something for your own people.”

For many, depression, anxiety, and PTSD are the realities of living in authoritarian states. During civil conflict and war, many more people suffer from these afflictions. A group of Iranian psychotherapists, doctors, and activist journalists have found that with support, encouragement, and understanding, people learn to cope.