At 22, Mohamed Mahdy was named among 12 emerging young photographers to watch in a New York Times story. A visual storyteller who achieved international stature early on, in 2022, he was featured in The Guardian's five young photojournalism talents, and last year, WorldPress Photo recognized Mahdy for his Here the Doors Don't Know Me project.

Mohamed Mahdy first became aware of the impermanence of things as a child, when he had to move frequently because of his father’s job in the port industry. Tossed about from one place to another, without being able to build friendships over time or feel a sense of belonging, this experience left a lasting impression on him and played a major role in the way he approached his artistic practice.

When he arrived in Alexandria as a teenager, Mohamed was looking for a passion, until one day, by chance, a colleague of his father’s suggested that he should try his hand at photography. “It was like a trigger, I told myself that it was a response to the feeling of temporariness that was in me, and a way of preserving memories,” he says. He joined a photography club and roamed the streets of Alexandria in search of models. The terrain was ripe for new discoveries, and the young man lost himself in previously unknown, sometimes very popular neighborhoods, meeting passersby from all walks of life. In Egypt, interactions between different social classes can be quite limited, which sometimes gives the feeling that several parallel and impermeable realities are adjacent to one another, without often meeting. Listening to peoples’ diverse stories during many chance meetings gradually altered Mohamed Mahdy’s perception of the world around him. In particular, he recalls an episode that he now considers “decisive”:

Back then, I would give a photograph to people who had posed for me as a thank-you. Two weeks after a session, as I returned to Labban (a very popular industrial district near Alexandria harbor) to give Ammo Saïd his photo, a man recognized me and told me that he had died a few days earlier. Stunned, I gave the stranger the photo and hastily wrote a message of condolence for Saïd’s family. A week later, when I returned to the neighborhood, someone asked if I was the photographer, and I assented. He informed me that Saïd’s widow wanted to meet me, and took me to her home. She was an elderly woman, crying and holding in her hands the portrait I had taken of her husband. She looked at me for a long time before asking me how I’d managed to do it, and told me that Ammo Saïd hated having his picture taken, so this was the only photo she had of him. As she thanked me, I realized that photography was a subjective thing, that you could capture a precise moment and freeze it, and that it could mean something else entirely to someone. It was then that I felt the need to create more stories that meant something to others.

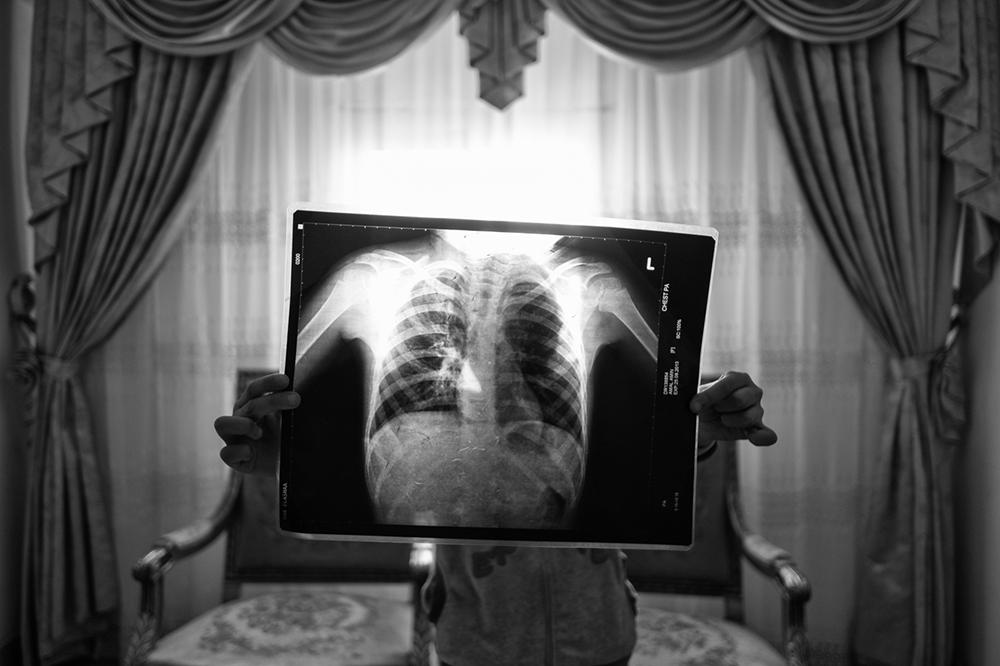

In 2015, while taking part in the Dubai Photo Forum invited by the HIPA Foundation (Hamdan International Photography Award), he met Spanish curator Monica Allende, who took the time to advise him, explain the ins and outs of the profession, and push him to embark on his first real photographic project. While he was looking for a subject, one of his university friends related that he had to move because his younger sister was seriously ill due to pollution in the city where the family lived. Mohamed decided to investigate in this suburb of the Alexandria governorate, where the Portland Cement Factory is located. Seeing the deplorable living conditions of the 60,000 inhabitants, half of whom suffer from chronic respiratory illnesses, including lung cancer and other eye and throat infections, he soon began to question the ethics of his approach: “How can I photograph and report if I’m not really experiencing the situation myself?” Thus, he decided to make regular return visits to a family, in immersion, and gradually met other residents. For a year, he photographed them in the intimacy of their homes, where illness was omnipresent. His own asthma worsened, much to the dismay of his mother, who didn’t understand his stubbornness in putting his health at risk.

It’s the sobriety of the shots in his early series Moon Dust that makes them so powerful: in black and white, they reveal a desolate landscape where dust covers everything, even the joys of childhood. At the same time, he is also making a short documentary film: “Sometimes images aren’t enough, listening to the testimonies of those affected is more powerful.”

By word of mouth, an editor from the New York Times heard about Moon Dust and got in touch to tell him that the daily would like to publish it. Thanks to this international recognition, things quickly got off the ground and doors opened: an exhibition was held in Cairo with the families, journalists came and the factory was again talked about at the national level, prompting those in charge to take action. Three months later, filters were installed, even though the inhabitants had been fighting for this for nearly eight years. The artist realizes the impact of his portraits and now knows what he wants to do: give a voice to the voiceless.

He doesn’t say much about his studies in art and design in Egypt, but he does say a little more about his year in Denmark, where he studied photography from the angle of social justice, as well as photojournalism thanks to a grant from the Magnum Foundation. If his collaborations with the press are rare, it’s above all a choice:

I often refuse assignments except when they correspond to the way I see my work. For me, photojournalism poses moral challenges: a photo is never just a part of reality, it remains subjective and the photographer must be able to be challenged. Citizen photojournalism, for example, enables a community to tell its own story with its own means and without any aesthetic concerns, which gives it great power. We’re currently seeing this with the war in Gaza, where there are no foreign journalists and Gazans are documenting their daily lives.

With Here the Doors Don’t Know Me, he deploys a philosophy of “empowerment” in which those who pose are not just subjects, but actors in their own representation. Until 2020, the population of a fishing village west of Alexandria, at the mouth of the Mahmoudieh canal, lived in the small, colorful houses that gave the area its nickname of “The Middle East’s Venice” for their picturesque character. In 2015, an urban development project sealed the fate of the 1,500 inhabitants: the village of Al Max was condemned to demolition and they had to leave. The authorities offered to relocate them dozens of kilometers away from the sea, which was not only their livelihood but also their way of life. Mohamed, who lives not far away in the Agami district, knows Al Max well, having walked past it for years on his way to university and having worked there as a street photographer.

Between 2016 and 2022, he worked with local residents to preserve their specific identity, which is in danger of disappearing. “One of the fishermen told me that he often found bottles with letters inside. This gave me the idea of using this medium to collect their memories and their relationship with Al Max. I didn’t give them any instructions as to what they should write — they were totally free. Gradually I realized that all these letters formed the collective identity of a community. There are poems, childhood memories of outings at sea, but also tragic tales such as the death of a son in the canal.”

In Here the Doors Don’t Know Me, the artist refuses to steer his work in any particular direction. He asks the question, “How do you want others to see you?” and then lets himself be guided. Residents chose how they wanted to be staged: in their home, with their family, or at the place where a loved one lost his or her life. “The fact that we don’t control anything makes it more authentic,” confesses the Alexandrian. Crowned in 2023 by the prestigious WorldPress (Open Format category), Mohamed Mahdy, combining art with commitment, gives a new dimension to the project by offering the possibility of communicating with the fishing community: “I felt it was the right thing to do to help them. With Moon Dust, people needed money to buy medical equipment, but with Al Max, they wanted to share their story with the world. After the award, they received many letters in several languages. As the WorldPress exhibition travels, I made sure that visitors could drop off a letter either in digital format using a QR code, or physically via an urn.”

Today, he continues to develop this project, using the 800 personal archive images collected as a medium for artistic experimentation, so that they are not just a vehicle for nostalgia: “I had this idea because in one of the letters, a local woman recounted how she made her young son touch everything around him, so that he could develop a sensory memory of the place. So, I began to visually mix these images with textures, like the pattern of wallpaper or the cracks in a wall. More generally, I’m interested in how future generations inherit the traumas of their forebears.”

Winner of this year’s Premi Mediterrani Albert Camus Incipiens, a book about Al Max is due to be published in 2025, thanks to a publishing grant.

Among his desires for the future, there is above all the wish to continue to anchor himself in Egypt with those who live on the margins and in oblivion, to tell their stories, all the more so as the international press no longer seems interested in the country since El-Sissi seized control, and Egypt appears to have turned its back on the aspirations of the 2011 uprising. This doesn’t mean that Mohamed has closed the door on working in other countries, but for now does so only when collaborating with artists from his own region, in order to get to the heart of the matter and meet his ethical requirements. While his portfolio also includes more intimate photographs linked to spirituality or what he calls “images of no importance,” it is driven by questions of transmission and memory that Mohamed Mahdy intends to pursue his path, with altruism as his compass.