Select Other Languages French.

Faced with internal turmoil in Iran — and competing, troubling narratives of what's happening — can art guide us to understanding?

LONDON—The images coming out of Iran over the past days have taken me back, unexpectedly and powerfully, to the year 2000, and to the first time I encountered the work of Shirin Neshat at the Serpentine Gallery.

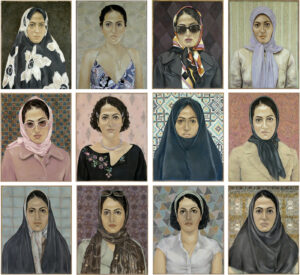

Neshat’s exhibition was stark and unsettling. Black-and-white photographs of women wrapped in chadors, their faces, hands, or feet inscribed with Persian calligraphy. At first glance, the images refused to tell you what to think. Were they celebrating the Iranian Revolution of 1979, or indicting it? The aesthetic borrowed from the visual language of revolutionary iconography, but it never resolved into propaganda. Instead, it held you in a state of moral and political uncertainty.

That ambiguity was deliberate. As several critics noted at the time, the Women of Allah series forced Western audiences to confront their own assumptions about Iran, Islam, and Iranian women. But if the still images left room for doubt, Neshat’s accompanying video installations did not.

One work in her trilogy, Turbulent (1998), has stayed with me ever since. On one screen, a male singer performs before a full, rapt audience. On the opposite screen, a woman sings alone, facing an empty hall. Her voice raw, almost primal. The piece was a devastating critique of Iran’s ban on women singing publicly, an indictment of enforced silence, made audible.

The Serpentine is one of my favorite art spaces in London, and I return to it often. I’ve seen many exhibitions there since, some excellent, some forgettable. But nothing has ever landed with quite the same force as Neshat’s did then. It wasn’t just art; it felt like an education.

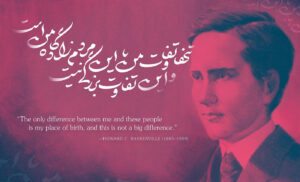

What has always impressed me about Neshat is her refusal to make easy or expected work. When she came to make her first feature film, Women Without Men (2009), she could have focused directly on the contemporary Islamic Republic. Instead, she went back to the 1950s, to the CIA- and MI6-backed coup that overthrew Iran’s democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, in 1953.

That coup is where so many of Iran’s modern troubles begin. Mosaddegh’s crime was nationalizing Iran’s oil industry, challenging British and American interests. His removal led to the consolidation of power under the Shah, an authoritarian regime that was pro-west, deeply unequal, and brutally repressive at home. The Islamic Revolution of 1979 did not emerge from a vacuum; it was shaped by decades of political suffocation that followed the coup. By choosing this moment for her first film, Neshat put her finger precisely on the historical fault line.

I fear deeply for the people of Iran when calls for “outside intervention” are made lightly. We have seen this film before.

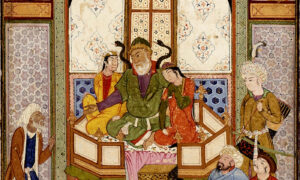

Years later, I was asked by the Iranian American actress Nazanin Boniadi to write a film treatment about the life of the poet Forugh Farrokhzad. Researching Forugh was a joy and a revelation. She was radically ahead of her time: fiercely independent, sexually frank, politically alert, and artistically daring. Her poetry articulated a yearning for personal and social freedom that existed well before the revolution. Forugh died in 1967, long before 1979, but her work captures the progressive dreams of an Iranian cultural elite that never got the future it envisioned.

At a screening of Shirin Neshat’s later film about the Egyptian singer Umm Kulthum, I introduced myself and later emailed her the treatment. She read it and responded generously. Sadly, Nazanin and I were never able to secure a producer. It remains one of those projects I wish had found its moment.

Forugh’s life, and Neshat’s work, remind us that Iran has always contained multitudes: radical artists, secular thinkers, feminists, modernists. The Islamic Republic did not invent repression in Iran, but it has perfected it. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini initially formed alliances with leftist and communist groups, only to crush them once power was secured. The result has been decades of violence, censorship, imprisonment, and fear.

Recently, there has been a disturbing claim circulating: that those of us who support freedom for Palestinians have somehow been “silent” on Iran, or worse, sympathetic to its regime because it backs Hamas. This is a slanderous oversimplification. I have no truck with any repressive regime. I believe politics and religion should be kept separate, everywhere.

At the same time, I fear deeply for the people of Iran when calls for “outside intervention” are made lightly. We have seen this film before. After 2003, Iraq was plunged into chaos following the US-led intervention, with estimates of excess deaths ranging from several hundred thousand to, in some studies, approaching a million. Whatever the precise number, the human cost was catastrophic. A similar collapse in Iran would devastate its people and unleash a refugee crisis on an unimaginable scale.

What I wish for Iran is change from within, however difficult, however unlikely it may seem under a regime willing to kill its own citizens en masse. And this is where I return, again, to Shirin Neshat. Her work has always resisted binaries: secular versus religious, victim versus villain. She critiques Iran’s rulers without erasing the complex history that led to their reign and condemns oppression without inviting catastrophe.

In this dire moment, her art feels newly urgent. A reminder that solidarity does not require simplification, and that justice, if it is to mean anything, must be rooted in nuance, memory, and care for human life.