HARLEM, NY—American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer, educator and singer John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie was an outspoken Baha’i. The double mural by artists Brandan “B Mike” Odums from New Orleans and Marthalicia Matarrita from Harlem, celebrates Gillespie’s hundredth anniversary of his birthday, in 2017. It was painted above Gillespie’s plaque on the Harlem Walk of Fame on 135th St.

Saleem Vaillancourt

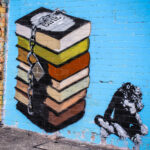

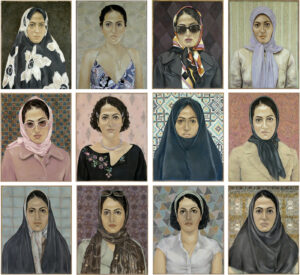

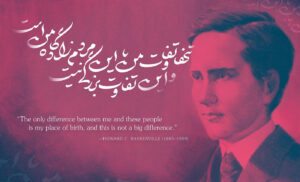

In Sao Paulo a young girl reaches up for books swirling in the sky. A snake coils round her leg on the ground. Women across New York stand reading or gazing into their own futures; though in Brooklyn, one woman wears a headscarf, her mouth erased, reminding us that oppression can sometimes win. A boy in Delhi is half-buried within the masonry of a building — his arms struggling from the brickwork to grasp at books and papers just out of reach. The eyes of the first black United States poet laureate, Robert Hayden, peer through thick glasses at a line of his own verse pasted on the side of a cinema in Detroit: “Undiscovered suns release their light.”

And in Harlem the most direct message of all stands painted across two chimney columns on a wall over a garden: the columns are bright yellow and have become the two halves of a broken ruler. The words “Made in Iran” stand high at the top.

Each of these murals was produced by the Education Is Not A Crime campaign to tell the world of a 40-year story of injustice.

kennardphillipps raise awareness of the persecution of the Baha’is in Iran. South African street artist Faith47 painted Atena Farghadani in a headscarf without a mouth. In 2016, Iranian artist and political activist Farghadani was sentenced to 12 years in prison for drawing a cartoon. She was released after 18 months. The mural was removed after being defaced by local reactionaries and later featured in the New York Times.

The Islamic Republic of Iran has persecuted the Baha’is, the country’s largest religious minority, since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. More than 200 Baha’is were executed in the early days of the new regime. Baha’is have been barred from public sector jobs, arbitrarily detained and jailed, defamed in the media and denounced as “unclean” and “apostates” from the pulpit. And just as Baha’i cemeteries were desecrated with bulldozers, so too were Baha’i children harassed by their teachers at school; the entire lifetimes of thousands of people have been shaped by state-sponsored religious persecution.

One of the most violent acts the Baha’is have faced has been the denial of their right to attend university. The move was a conscious policy, captured in a 1991 memorandum signed by Iran’s Supreme Leader, to “block the progress” of the Baha’i community and to try to strangle their existence.

The Baha’i community in Iran found a unique and positive way to overcome this discrimination. In 1987 they created the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education: an “underground” university that held classes in people’s living rooms so that young Baha’is could study. Today thousands of its graduates have attended some of the best universities in the world for postgraduate work and the BIHE still serves a community dedicated to education regardless of the ban.

The constructive resilience of the Baha’is in Iran inspired Education Is Not A Crime. The campaign was started by Maziar Bahari, an Iranian-Canadian journalist and documentary filmmaker, himself not a Baha’i, who was looking for an uplifting yet effective way to defend the rights of the Baha’is in his native Iran. Between 2015 and 2017 the campaign produced more than 40 murals in New York, Detroit, Atlanta, Los Angeles, London, Sao Paulo, Cape Town, Delhi and Sydney, celebrating education and drawing attention to the denial of this right to the Baha’is.

For years the Baha’i community and organizations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, as well as United Nations special rapporteurs and an array of diplomats, human rights experts and public figures, have used every tool available to raise awareness of the situation facing the Baha’is. Reports were issued and UN resolutions passed — all of it helping to mitigate the worst of the Iranian government’s actions. But with our campaign we also wanted to involve the public in these calls for justice.

Public art was the solution offered by Education Is Not A Crime. My colleague Rachel Wolfe and I moved to New York to help our curator, Andrew Laubie at Street Art Anarchy, and our community lead, Ayana Hosten, to produce more than 20 murals across Harlem in just a few months. Dozens of street artists from across the US and around the world joined us. And in the course of our work in Harlem we befriended local pastors, anti-gang mothers of sons lost to gun violence, the NYPD, cultural ambassadors and artists.

Harlem became the spiritual home of Education Is Not A Crime. Many African Americans related to the situation of the Baha’is; after all, here was one community of struggle recognizing the efforts of another, to achieve justice, to live in equality, and to be free.

Our film about the campaign, Changing the World, One Wall at a Time, was broadcast on satellite inside Iran. Millions of people saw it during its repeated airings. The subject of one of our murals, a woman named Nasim, now living in California but originally a Baha’i from Tehran, says she received many messages of support from her fellow Iranians.

I do wonder sometimes: what did we achieve? The Baha’is in Iran are still denied the right to study. No amount of media attention has changed that so far. But then I remember the words of George Faison, the first African American winner of the Tony Award, who welcomed our mural on his Firehouse Theatre in Harlem. “We are all in the same battle,” George said. “And any time you can give inspiration, even just subliminally … it will come back to you. That’s what art does.”