In these excerpts from her memoir in verse, Abacus of Loss, poet and translator Sholeh Wolpé evokes a day in the cemetery with her parents and a decisive moment while in transit at the airport.

Sholeh Wolpé

Practicing Absence

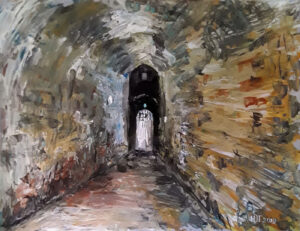

We’re attending a funeral in the same cemetery where our

parents have bought their burial plots. After the service they insist

we walk over and see. There’s a bench, says Daddy, and a shade

tree. In case you want to come and visit. Often, I hope.

She doesn’t come often when we are flesh, says Mama, why would

she come when we’re just bones? She then rings an arm around

mine and we navigate the graves.

Mama’s knees buckle with every step.

She, who always glided as if on rollerblades.

Daddy walks ahead, careful not to step

on the names of the dead.

We goad our parents to lie down.

And to our surprise, they do.

Even the sparrows suddenly fall silent

as we lift up our phones to capture

our parents practicing their own absence.

At The Airport

Sitting with three open books black with the meandering

calligraphy of a “terrorist language” at an American airport

is a terrible idea.

But five hours early, what’s a girl to do but risk it, open what

she must under the watchful eyes of TSA and cameras that

blink when a person of unknown dark curly-hair origin is

spotted with undecipherable texts, possibly manuals for mass

destruction of something.

A few people pass by, too casually perhaps, and peek at the

books, but in the end, it’s a sweeper who soft-shoes his way

towards me, a Latino Fred Astaire with fake bushy mustache.

He runs his broom to and fro, moving dust closer and closer to

my ridiculously high-heeled red shoes, then stops. He pretends

to notice me for the first time, puts his small chin on the stick of

his broom, gathers his mouth as if around a cut lemon,

squints, then asks in Spanish, ¿Que es esto? Greico?

Good move, I think, so you no hablas inglés, amigo. I look up

and give him a sly smile. He parts his lips, slightly. His teeth are

corn-yellow. A smoker for sure. But that mustache? It takes all my

strength to not reach up and pull. To see if it comes off.

I answer in Spanish, No, this isn’t Greek, it’s Persian poetry.

He lifts his chin, says, ¡Bien! ¡Hablas Español! He then bends over

the book for a closer look. I say, this time in English, Poetry, and

point to the shape of the couplets. See? I say, A line of Persian

poetry consists of two hemistiches separated like this. I point to the

blank space between separated texts. He ungathers his lips

from their concentrated pose, nods, mumbles something

about how he hated memorizing poetry at school, then in

perfect accent-less English: Don’t miss your flight.

With that, he turns on his heels and just as deliberately, soft-

shoes back, towards some place, over there, broom still in

hand, past a door that appears and disappears like an itch,

scratched.