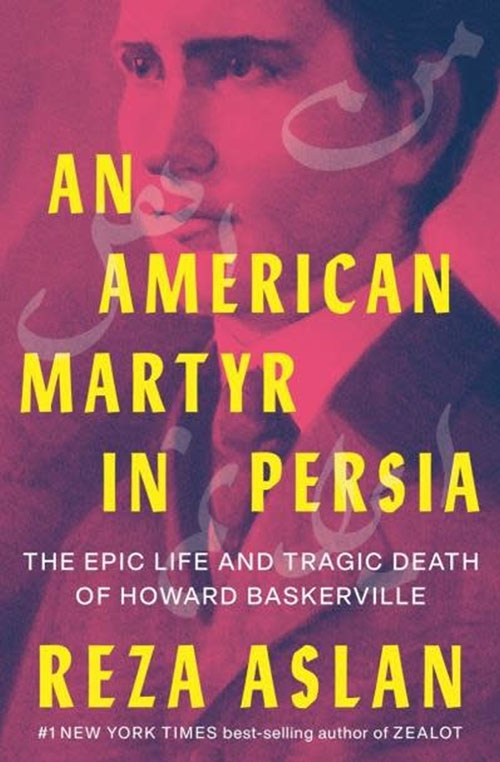

Every year, thousands of Iranians would visit Howard Baskerville’s grave in Iran to honor the American who gave his life for their cause. In this rich and illuminating biography, Reza Aslan presents a powerful parable about the man whose fame would be tied not to his life, but to his death, while investigating the universal ideals of democracy — and to what degree Americans are willing to support those ideals in a foreign land.

An American Martyr in Persia: The Epic Life and Tragic Death of Howard Baskerville, by Reza Aslan

W.W. Norton and Company 2023

ISBN 9781324065920

Dalia Sofer

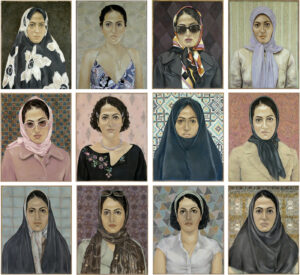

If the Qajar kings, who ruled Iran — then known as Persia — from 1789 until 1925, were alive today, they would most likely be avid social media users. Astute curators of their public image, they portrayed themselves as both inheritors of an ancient civilization and proponents of modernity. Fath Ali Shah, in power from 1797 until 1834, commissioned multiple oil paintings that depicted him not in realistic terms but as an idealized symbol of both power and refinement. These paintings decorated his palaces (among them Negarestan and Golestan in Tehran), and were sent as diplomatic gifts to such nations as England, France, and Russia, with whom he wished to foster closer ties. His descendant, the Europhile Naser al-Din Shah, who ruled from 1848 to 1896, developed a fascination with photography and formalized its instruction at the Dar ul-Funun, an academy of sciences that he founded in 1851. He commissioned multiple photographers to portray him and his court, and dabbled in the art himself, frequently photographing his 84 wives in various states of leisure. After his assassination in 1896, his son Mozaffar ad-Din, now the new Shah, developed a preoccupation with cinema.

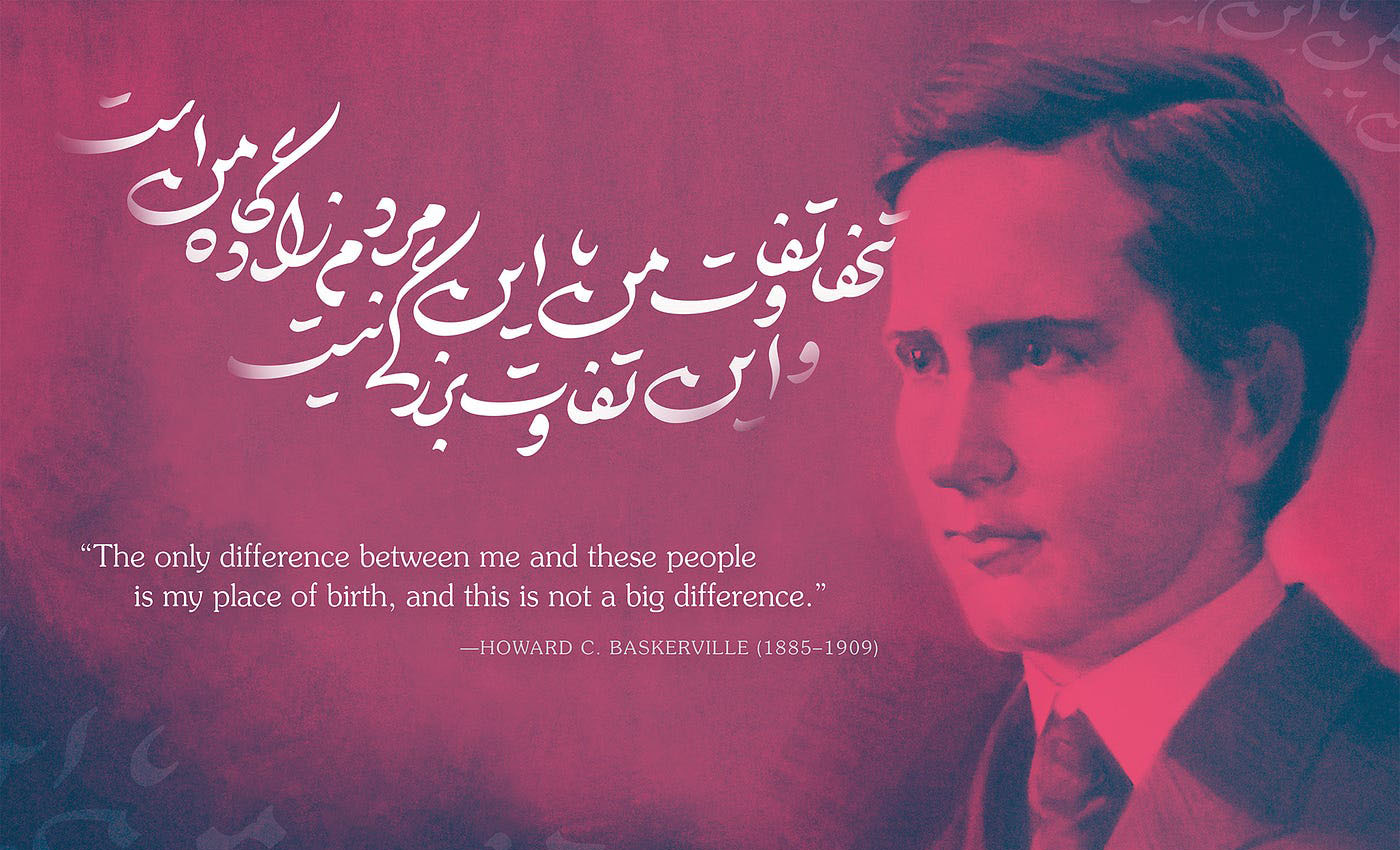

The popularization of photography and film meant that these mediums could no longer be limited to the court’s public relations messaging. As discontent with the monarchy’s economic concessions to foreign powers — especially Britain and Russia — grew, uprisings paved the way to what became known as the Constitutional Revolution, resulting in 1906 in a constitutional monarchy that Mozaffar ad-Din begrudgingly recognized but which his son and successor, Muhammad Ali, vigorously fought against. Essential to this revolution were photographs and postcards of the revolutionaries (known as “nationalists”), images that negated the established narrative of the Qajar kings and presented a counter-narrative of a nation steeped in the ideas of the Enlightenment. Among the pivotal figures who gained notoriety thanks to their widely-circulated images were the leaders Sattar Khan and Baqer Khan; another was the American missionary Howard Baskerville, whose fame would be tied not to his life, but to his death.

It is this latter figure that Reza Aslan explores in his captivating book, An American Martyr in Persia: The Epic Life and Tragic Death of Howard Baskerville.

Aslan, a religion scholar and television host who has previously written about such enigmatic figures as Jesus (in Zealot, the Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, Random House, 2013), and God (in God, a Human History, Random House, 2017), here turns his attention to yet another perplexing, albeit earthlier, figure. Howard Baskerville, a Presbyterian preacher’s son born in Nebraska and raised in South Dakota, studied at Princeton University (a school founded by Presbyterians) with the future president Woodrow Wilson — at that point the college president and a sought-after lecturer who emphasized the propagation of American democracy and viewed religion as a vehicle for public service. In 1907, after adopting Wilson’s belief that “individual salvation is national salvation,” Baskerville traveled as a missionary through the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions to Persia, becoming a teacher at the American Memorial School in Tabriz, a multicultural city that had played a pivotal role in the revolution and was still at the forefront of the resistance to Muhammad Ali’s efforts to undo the constitution. (In August 1907, prior to Baskerville’s arrival, Russia and Britain — unbeknownst to Persia — had signed an agreement in St. Petersburg known as the Anglo-Russian Convention, dividing Persia into two zones of influence, with Russia controlling the north and Britain the south. This only fueled the revolutionaries’ exasperation with the Shah’s ineffectuality.)

Joining the devoted community of American missionaries who had been in Persia for multiple generations, Baskerville initially avoided politics as he was instructed to do, but after forming friendships with his Iranian students and others, he joined the fight, much to the displeasure of both the West Persia Mission and the American government, causing the first to disown him and the latter to revoke his American citizenship. The 24-year-old Baskerville didn’t waver. He relinquished his passport and allied himself with Sattar Khan and his fighters (known as Feda’i), and on April 20, 1909, he was shot during a standoff with the Shah’s forces. Hailed by the locals as a hero, he was nicknamed “The American Lafayette,” and his funeral, attended by thousands, contributed to the Shah’s decision to lift a devastating siege on Tabriz and concede to his opponents, at least for a time.

Aslan vividly portrays, in the book’s first part, Baskerville’s early life and education, his travels from the United States to Persia by way of Europe, his gradual embrace of his role as teacher, and the history of the West Persia Mission, whose strategy was to focus not on direct conversion of Muslims, but on an initial conversion of local Christian communities (including Armenians, Assyrians, and Nestorians), whom it considered as belonging to “the degenerate churches of the East.” Once converted, these communities would be encouraged to evangelize to Muslims, in a process known as “the Mohammedan work.” The book’s second part offers an absorbing account of the Constitutional Revolution, focusing on the dynamic figure of the commander Sattar Khan, the involvement of the clergy (some of whom were in favor of the revolution, some virulently against), and the pervasive influence of the Russian government on the Shah. The last part returns to Baskerville, recounting his entrenchment in the fight and his subsequent death, concluding with an epilogue that traces the downfall of both the revolution and the Qajar dynasty, and the eventual rise of Reza Khan, a commander of Muhammad Ali’s Cossack Brigade. After declaring a military coup in 1921, Reza Khan would go on to become prime minister in 1923 and king in 1925, attempting, as had his Qajar predecessors, to imbue himself with the aura of the Persian Empire. (The surname “Pahlavi,” which he adopted, was the name of the language of the Sasanians — the last dynasty prior to the Muslim conquests of the seventh century.)

What makes Aslan a gifted storyteller is his knack for evocative language. He describes Woodrow Wilson’s face, for example, as “an almost perfect rectangle framed by a high, flat forehead and an aggressive jaw that jutted out like an admonition.” The city of Tabriz is likened to “an old clay vessel that had been repeatedly shattered and put back together again, the cracks and fissures no longer concealable.” And the tips of Naser al-Din Shah’s mustache are portrayed as “so sharp, you could impale a prisoner on them.” He is also skilled at narrowing down complex historical events to their essence, making them accessible to a wide readership.

But one risk of simplification is oversimplification, as happens for example, in the description of Paris in 1907, when Howard Baskerville passed through the city on his way to Persia:

These were the final few years of La Belle Époque, a period of supreme civilizational confidence for the French: an era that produced the Eiffel Tower, the Grand Palais, the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur. A brisk stroll down the Montmartre and Baskerville could glimpse Monet, Matisse, and Modigliani sipping au laits at a sidewalk café. A stop for tea at the Hôtel Ritz and there’s Marcel Proust, who has his own private room, tinkering with Remembrance of Things Past. Across the Seine, Marie Curie is giving lectures on physics at the Sorbonne: the first woman ever to teach there. She had just won her first Nobel Prize four years ago; she will win another in four years’ time.

While this is an alluring portrait of Paris at the turn of the last century, it omits the harsher realities of the time, including, for example, the fact that the Sacré-Cœur was built just after France’s defeat in the 1870 Franco-Prussian war and the brutal 1871 massacre of the Paris Commune, as a rebuke by conservative factions to a population that they believed had lost its “moral compass”; or the fact that in 1907, as Baskerville passed through Paris, France was still feeling the tumultuous reverberations of the recently concluded Dreyfus Affair, which for over a decade had split society into the opposing camps of “Dreyfusards” (supporters of Dreyfus, among them Marcel Proust) and “Anti-Dreyfusards,” (his detractors).

The romanticization of Paris does not, in itself, detract from the overall point of the book, but it does bring up an important question: how does the historian writing for a general audience write a “good story”? Aslan, who straddles both academia and popular media, is no doubt familiar with this conundrum, and to a large extent, he gets it right. But on occasion one wishes he would go a little deeper. He mentions, for example, that the nationalists’ “fundamental goal was to marry traditional Islamic principles with modern concepts such as individual rights and popular sovereignty to create a truly indigenous democratic movement,” and goes on to explain that the constitution they founded guaranteed basic rights and freedoms for all Persians. But a more thorough investigation would have shed light on how the movement, while “borrowing language and ideas from Europe and the United States, was firmly grounded in a century or more of Persian political thought.” (The political expression of Islamic principles was also at the root of the ideology of many of the thinkers of the 1978-79 revolution, whom Michel Foucault famously referred to as proponents of “political spirituality.”)

It is possible that Aslan did not wish to burden the American reader with the intricacies of Iranian political thought, and this may be a fair consideration. But this leads to another fundamental question: why tell the story of the Constitutional Revolution through the figure of Howard Baskerville? Sattar Khan, after all, to whom the book deservedly devotes a large portion, is a far more dynamic figure. Aslan answers the question himself in the book’s introduction:

I wrote this book because I believe every American and every Iranian should know the name Howard Baskerville, and that name should be a reminder of all the two peoples hold in common. My hope is that his heroic life and death can serve in both countries as the model for a future relationship — one based not on mutual animosity but on mutual respect. Perhaps then, America can once more be known as a nation of Baskervilles.

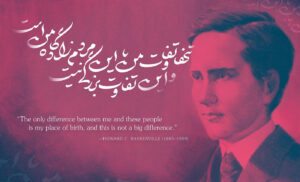

While a desire for a rapprochement between Iran and America is a noble sentiment — and one that many of us hyphenated Iranians only dare dream about — enlisting Baskerville for the cause feels like a shortcut. Baskerville’s decision to take up arms on behalf of the nationalists was laudable. As he said to William Doty, the United States Consul General in Tabriz, “The only difference between me and these people is the place of my birth, and that is not a big difference.” But as Aslan himself argues, Baskerville joined the fight not despite the fact that he was a Christian missionary and an American, but because of it. He had traveled to Persia with the intent to “save the souls” of the locals — first the Christians, later the Muslims. That in the end he chose to manifest this mission through political action doesn’t detract from the fact that he was not driven by humanism but by an evangelical duty. As Aslan eloquently explains, “[…] Baskerville had not abandoned his American identity. On the contrary, this was him exerting it. He had not renounced his faith; this was him putting it into practice. And he most definitely had not withdrawn from ‘the Mohammedan work’; he had merely taken it from the chapel to the streets.” Bearing this poignant clarification in mind, what does it mean, then, to have a “nation of Baskervilles”? Was the evangelical mission in Persia not problematic to begin with?

Baskerville’s death turned him into a symbol of solidarity with the Constitutional Revolution. Sattar Khan, who knew all along that the young man was not a seasoned fighter (he had asked him to research explosives and other military tactics in the Encyclopedia Britannica!), nevertheless named him second-in-command and agreed to allow him to forge ahead in what he no doubt knew would be a suicide mission. This prompted some of Baskerville’s colleagues to speculate that the great commander was using the young American as a public relations pawn. As Aslan writes, “Perhaps there was something to the accusations being flung by the Americans that Sattar had some nefarious plan in place for Baskerville. After all, one American fighter would not save the cause. But one dead American fighter — that could change the course of the revolution.”

And that is, in fact, what happened. Baskerville became at once more and less than a man: he became a symbol. As news of his death and images of his funeral circulated, he was hailed as a hero, and has since often been referred to as “an American martyr,” a moniker that’s confounding at best. Martyrdom, after all, is a religious concept, one recognized by all three Abrahamic religions. In Shiism, it stands as a bedrock of faith, evoking the martyrdom of Imam Hossein in Karbala. Yet Baskerville was no Shia martyr. If he died as an “American martyr,” he did so as a proponent of Manifest Destiny — the belief that America has a God-given destiny to duplicate its own image elsewhere. To remember why he died feels just as crucial as specifying how he died.

Aslan’s book, rich and illuminating, would have been even more eloquent had he allowed Baskerville to be just a man — no more, no less.