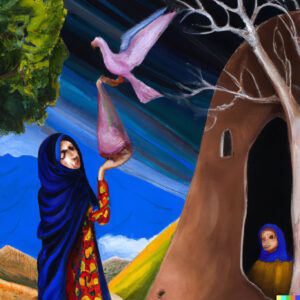

For a Taliban fighter, nationality is linked to religion and identity. For a woman living under strict Sharia law in Afghanistan, religion threatens the meager personal freedom she has left. Haunted by fear and fragile hope, two couples cross the Afghan capital and accidentally meet. Where is the common ground between them?

Translated from Pashto by Asad Narim

Sara

It was the middle of summer. The weather had turned blisteringly hot. As soon as the sun rose above the mountains, Kabul began to boil like a pot on the fire. With electricity often cut, fans and coolers would sit unused most of the time. People would get through the daytime heat inside the house, but the nights were unbearable.

The rooftop where Sara lived was enclosed by a low wall and railings. She was grateful for this and during the summer she slept there with her husband. Cool air drifted across the roof and a breeze swept over their heat-stricken bodies. The experience reminded Sara of her childhood, when she had delighted in sleeping under the stars with her parents, sisters, and brothers.

Every morning after waking, Sara folded and stacked the bedding, and carried it back into the room. Because the sun struck the rooftop directly, the chore always left sweat streaming down her face. Wiping her forehead, she straightened her back and let out a long “oof” in protest. She gathered the beds and went down the stairs to the hallway, then into a room where her husband sat in the corner, absorbed with his phone.

“Waheed, this year’s heat is brutal,” she said.

Without looking up, he replied, “It’s not that hot — you’re exaggerating.”

As she obsessively smoothed the wrinkles on the stacked bedding, Sara retorted, “You’re sitting comfortably in the shade. If you were hauling the beds in the sun, you’d know how hot it is.”

Still preoccupied, he said, “You didn’t need to bring them in. We’ll be sleeping on them again tonight.”

Her throat tightened with frustration. “Yes, of course. I’ll just leave them outside so the mattresses and covers rot in the sun — since we don’t have the money to buy new ones.”

Waheed had no answer. He had lost his position with the government when the Taliban returned to power. Their situation was getting worse by the day. However hard he searched, he could not find work. She knew he consoled himself with the thought that half the country was unemployed. But she, too, had no work; Sara had lost her job with the NGO, and now because of the ban on women’s work, she could no longer earn money; even worse, she was confined to four walls, as if she were under house arrest.

She returned from the kitchen, carrying a tray with a thermos and glasses. She let it drop harshly onto the floor, as if the tray and its contents were to blame for all her troubles, and she was taking revenge on them. The glasses clinked against one another. Waheed lifted his head at the noise but said nothing.

Sara spread the cloth on the floor. With a lump in her throat, she said, “Come, have breakfast.” She spooned sugar into her glass, poured tea from the thermos, and tore off a piece of bread, chewing and swallowing it with a loud gulp. Her movements were hurried, restless, dissatisfied.

Waheed moved over to the food, put down his phone, and poured a glass of tea.

Moments later, Sara suddenly broke into sobs, tears spilling from her eyes and running down her cheeks.

Waheed stirred sugar into his glass and looked at Sara. She seemed depressed, her face pale. She was no longer the woman who began her mornings full of energy, chatting cheerfully over breakfast about her work, friends, and goals. Now she was sensitive, often moved to tears without warning.

She had also developed a strange obsession: when she thought she heard noises she constantly shifted the hiding places of her education and work documents. She explained it was out of fear — because she had been employed by an international organization, she believed she might be arrested if the papers were found. Waheed tried to prevent her from surrendering to these anxieties, but his efforts were fruitless. He reassured her that she had done nothing wrong, and reasoned that her work with the NGO was purely humanitarian. But she wouldn’t be convinced: she continued to feel she was in constant danger, listing all the terrifying stories she had read on social media, and heard from others, to justify her fear.

Waheed felt sorry for her. Gently, he asked, “Sara, why are you crying?”

A tear slid down her cheek. “I don’t feel right,” she answered, “Mornings are meaningless when you have no purpose.”

Waheed knew she was right, but he felt powerless. There was nothing he could say that would help.

A few minutes passed in silence. When her tears subsided, Sara said, “There was a lot of noise in our street last night. I think the Taliban searched the neighbor’s house.”

Before he could reply, she asked with a frown, “What did you do with the previous government’s tricolor flag?”

Waheed tried to lighten the mood with a joke. “This morning, while you were busy collecting the bedding, I hung it over the courtyard door.”

Sara gave him a pained look.

Softly, Waheed said, “Relax. You don’t have to be afraid. Don’t overthink — those thoughts will only create needless worries.” He continued, “Go for a walk around the market today. I’m heading out to meet a friend and then I’ll look for work.”

“Where should I go? At least you can search for a job. I have nowhere — parks and entertainment venues are closed to women,” she replied listlessly.

“If the parks are closed, then walk through the streets. Even if you don’t buy anything, it will lift your spirits to see the shops and people,” Waheed said with a smile.

Sara said nothing. The thought of walking through the city after being shut indoors for so long didn’t displease her.

The midday sun was scorching, but Sara didn’t mind. It was the first time she had left the house in nearly a month. She enjoyed taking in the sights of people, shops, and passers-by. The everyday scenes she had once overlooked while busy with work now fascinated her. It felt as though she were seeing her birthplace, a city she had lived in half her life, for the very first time.

She decided to visit a market known for its good trade and female shoppers. Boarding the city bus, she found all the seats occupied. When the driver asked her to get off, she refused, insisting she would stand. The driver begged her to leave, until two women on a double seat shifted over and invited her to join them. Sara sat, but was upset by the driver’s behavior.

“Sister, don’t be angry with me,” the driver explained. “The doctors are patrolling the streets today. If they see you standing in the bus, they’ll arrest me and take me to the police station.”

Sara glanced at the woman beside her, puzzled. The woman laughed and explained that the driver was referring to the morality police of the Vice and Virtue Ministry — they wore white coats just like doctors. Sara, finally grasping the joke, smiled too.

The market was crowded. Women wandered around shopping, while shopkeepers bargained busily with their customers.

Sara went into several shops. In one, a beautiful Afghani-style dress caught her eye. She lifted it from the hanger and held it before the mirror, sizing it against herself. The dress was a rich shade of purple that complemented her pale skin perfectly.

“How much for this dress?” she asked.

“Three thousand Afghanis,” the shopkeeper replied. “But if you’re serious, I’ll give you a discount.”

The price stunned her. She had no money for clothes. Handing the dress back, she hurried toward the door.

“Come back! I’ll let it go for two thousand!” the man called after her, but Sara walked quickly away, her chest tight with sadness. Their loss of income broke her heart. She recalled the time when she was paid monthly in dollars, and could buy any clothes she desired.

Sweat burned above her lip. The heat had intensified. She pulled the mask down from her nose and mouth to rest on her neck, and wiped her face. She kept walking until she reached a row of flower shops. Their freshness and color brought her joy: bouquets of red and white roses, daisies, irises, and pansies spilled from the vases outside. They had been put there to attract customers. Sara closed her eyes and inhaled deeply, the mingled scents of the flowers dancing through her senses.

She exhaled easily, and was about to draw another breath when a harsh voice startled her: “Cover your hair, sister! Why aren’t you wearing your mask?”

Sara froze. Her skin seemed to melt, as though she were a plastic doll held to a flame. Fearfully, she turned toward the voice. A man with an overgrown beard stood nearby, turbaned, dressed in a white coat. His eyes burned with anger.

Morality police, Sara whispered to herself.

The voice rang out again: “Pull your headscarf up and put on your face mask. You are a Muslim woman.”

She snapped to attention, lifting her veil to her eyebrows and pulling the mask back over her nose and mouth.

Satisfied, the Vice and Virtue inspector moved on, stopping next before a boy who was passing by. “What kind of pictures do you have on your phone?” His tone was sharp.

“Family photos, mullah sahib,” the boy stuttered.

Sara hurried away. Still shaken, she decided to return home and went to the bus stop. She blamed herself for having left the house at all. An intense wave of anxiety gripped her. She tore a thread hanging from her hijab, and nervously wound it tightly around her finger. She felt the Morality Police closing in, ready to arrest her at any moment. Her mind went to a girl who had been arrested not long ago. After enduring much humiliation — justified as a warning — she had been released with a guarantee from her father that she would always observe the hijab.

As Sara waited, her phone suddenly rang. Waheed. He asked her how her day was going. Sara answered in a trembling voice that she would tell him about it when she got home. He asked her to meet him in a nearby restaurant, but she refused, saying that she didn’t feel safe and wanted to return home as soon as possible. He said it would do them good to eat out together. He insisted.

In the restaurant, they passed through the dirty dining area where men were eating, and climbed the narrow staircase. The stairs wobbled and creaked under each step. On the second floor, they reached the family section. A waiter greeted them and showed them to a table. Sara was tense.

“We don’t have any money. How are you going to pay for kabab?” she whispered to Waheed.

“I told you this morning. I was meeting a friend. He owed me some money and paid me,” he answered in a lowered voice.

They sat opposite each other and soon the waiter came to take their order.

“Kabab!” they said in unison, and laughed at themselves.

As the waiter left to prepare their meal, Waheed busied himself with his phone. Sara, disliking that he was distracted, looked around the restaurant. It was grimy — the curtains, doors, and windows appeared to not have been cleaned since the place had opened. Tables and chairs were cluttered; the overall mess was hard to ignore.

She observed the other customers: a middle-aged man and a young woman who were cheerfully chatting at a table.

For a moment, Sara was glad to see the woman happy. But her happiness vanished quickly when doubt crept back into her heart — would the Taliban soon ban women from restaurants, too? When the man and woman left the restaurant, Sara and Waheed were the only guests.

She returned her attention to Waheed. “Wasn’t there a better place than this?”

He glanced around, “Why? What’s wrong with it? My friend gave me this address; he said the kabab is delicious and reasonably priced.”

Sara missed the old days when Waheed had taken her to fancy places. Everything had changed now.

The restaurant, which had fallen quiet after the couple had left, grew noisy again. A thin, sunburnt man in his thirties entered, carrying a rifle, followed by a woman in a burka and two disheveled children.

Sara felt a surge of fear when she saw the Taliban fighter. Her anxiety eased slightly when she noticed he was with his family. She found it unusual — she had never seen a Talib with his family before.

The waiter placed a plastic tray with kabab skewers and some bread in front of her and Waheed. For a moment, she forgot the Talib. She sprinkled chilli and ghoora powder on her kabab, tore a piece of bread, and pulled the meat from the skewer. Waheed followed her lead, and they both began eating. The kabab was indeed delicious.

Mid-bite, Sara felt a heavy gaze on her. Turning slightly, she saw the Talib staring at them. At first, she dismissed it as normal, but soon realized his eyes remained fixed on them. Fear shot through her heart. From his expression, she understood he was questioning the nature of her relationship with Waheed — much as she had done with the previous customers. Her appetite vanished. She wished she had brought her marriage certificate, just in case. She ate cautiously, keeping him in the corner of her eye.

The waiter approached the Talib’s table. “What can I get you, Mullah sahib?”

The fighter asked why men and women were seated together. The waiter, seemingly accustomed to such questions, replied patiently, “Mullah sahib, you’re new here. This is the family section. Men come here with their families to eat.” Then he repeated, “What can I bring you?”

“What do you have?” asked the Talib.

“Qaboli, palow, karaei, dashi, kabab, chayneki,” the waiter recited the menu.

The Talib scanned the restaurant and said, “Four orders of kabab.” The woman with him tried to lift her burka’s face screen, but he stopped her with his hand. She obediently lowered it again.

The waiter brought their food. The Talib stood, picked up the tray of food, and motioned for his wife and daughters to follow. The family moved to a table by the window, with their backs to Sara and Waheed.

Sara immediately realized what he meant by this. And for the second time that day, she felt happy to have escaped the Talib’s clutches. She finished her kabab quickly and stood.

“Why are you in such a hurry? Wait until I’ve paid, then we can leave.” Waheed looked up, surprised.

Still hurrying, Sara said, “Let’s go and pay together.”

Outside on the sidewalk, Waheed asked why she had been scared.

“Didn’t you see that Talib staring at us?” she replied. Waheed tried to brush it off with a “no” but their eyes met. Sara realized he had seen everything, and was only denying it to calm her down.

Sara vowed then and there: from now on, for her own safety, she would only leave the house when absolutely necessary.

Hafeez

The call to morning prayer roused Hafeez from sleep. Murmuring bismillah, he rose from his floor bed. The sky was still dark as he stepped outside. He sat by the stream running through the courtyard to perform ablution. Smoke curled from the flue above the oven room in the corner, where his wife, as usual, had already risen to bake bread.

After drying his face with a handkerchief, Hafeez left the courtyard and set off toward the mosque. He hadn’t gone far before realizing he had left his weapon behind. Cursing the devil, he felt suddenly exposed. What if an ambush awaited him and he was unarmed?

He turned back and called out, “Anisa, bring my Kalashnikov!”

A skinny girl of five or six, hair tousled and eyes heavy with sleep, appeared in the doorway, scratching her head. Hafeez barked again, “Bring the Kalashnikov!”

She darted inside and soon re-emerged, struggling under the weight of the rifle. Hafeez snatched it from her, slung it over his shoulder, and felt relief settle over him. He hadn’t taken two steps when he remembered something. He had taken the day off work to take his wife to see the doctor in Kabul, but had forgotten to tell her.

He turned to the little girl, “Tell your mother to prepare breakfast early today. We must reach the city on time.”

Hafeez left the house and walked down the narrow alley towards the mosque. He was anxious: he didn’t like the idea of going to the city, especially with his wife and daughters. He didn’t feel safe there, and had heard that when village women went to Kabul their behavior changed drastically, and they were pulled away from their traditional roots.

The corner of the yard where the tanoor stood seemed farther than usual. Anisa skipped towards it, and then delivered her father’s message to her mother, who was leaning halfway into the clay oven.

Momina pulled out a piece of bread and placed it in the basket at her side.

When her mother didn’t respond, Anisa blurted eagerly, “Adi, didn’t you hear me? Father said to make breakfast early so we can eat and head to the city!”

As she set the bread in the basket, Momina gave her a doubtful look. Anisa, used to this, protested: “I swear.”

Momina rubbed her stinging eyes. “Your father didn’t tell me anything last night.”

“He told me just now,” replied Anisa. Momina believed her this time and was excited. Her expression was one of joy.

She put the bread in the basket, and said, “Why are you staring at my mouth? Go wake Zainab. Wash your faces and get ready! If we’re late, your father will be angry — and we’ll only see the city in our dreams!”

She handed Anisa the tea glasses and sugar. Anisa hurried off, only to return moments later.

“I forgot the glasses,” she admitted sheepishly. Bursting with happiness, she snatched up the tray so quickly the glasses clinked against each other. Her mother called after her to be careful.

Anisa shook her little sister awake.

“Get up and wash your face. We’re going to the city!”

Zainab, about four years old and rounder than her sister, stirred and rose. The two joined hands and spun around the room, laughing.

“Will our mother’s illness get better in the city?” Zainab asked cautiously.

“Yes. Maybe we’ll even have a brother, and Father won’t marry another woman,” Anisa replied brightly.

The sun was just beginning to rise over the mountain peak when the family reached the roadside and proceeded to wait for a car. Hafeez raised his hand, but vehicles sped past without stopping. The route taxis were full, and the private cars returning from holidays in other provinces refused to pick up strangers — least of all a Taliban fighter with a rifle. As time passed, Anisa and Zainab grew weary and sat on the ground.

Hafeez’s temper flared.

“The bastards won’t stop because I’m a Talib and armed. If it were up to me, I’d ban them from travelling to other provinces. God knows what immoral things they’re doing there.”

At last, even he grew tired.

“Let’s go back. We’ll try another time,” he told his wife. But Momina pleaded with him to wait a little longer. “When Gul Mir’s wife went to Kabul for treatment, she had a child after seven years.”

Hafeez said nothing. He kept flagging down cars, his silence heavy with frustration — at the harshness of village life, the lack of healthcare, the absence of female doctors to treat women’s illnesses.

By the time a car finally stopped, the sun was fully up. Hafeez hurried his wife and children inside, and then climbed into the front seat.

“Mullah sahib,” asked the driver attentively, “where are you going?”

“To Kabul,” Hafeez replied. The driver switched on the radio. A Talibani nasheed — without music — filled the vehicle. Hafeez was pleased with the choice, and remarked that he was glad the jihad had succeeded and the infidels had left the country.

“Indeed. I only wish poverty and unemployment had left as well,” the driver muttered, mocking. Hafeez caught the sneer but stayed silent. They had no alternative transport, and his superiors had ordered him to treat people well. Often, he resented how bound he was — forced to compromise, to overlook violations that gnawed at him.

An hour into the journey, Momina felt stifled. As the sun climbed, the heat inside the car grew unbearable. Beneath her burka and scarf she could hardly breathe. At last, she lifted the face veil. Even then, only her eyes showed, so Hafeez ignored it. Her nose and mouth were still covered.

Moments later, the driver adjusted his rearview mirror. Hafeez reacted instantly. He spun around and ordered his wife to lower her veil, then, without a word, snapped the mirror upward.

“Why did you do that, Mullah sahib? Without the mirror we might crash,”protested the driver.

“The rearview mirror is an invention of infidels,” Hafeez shot back. “It’s good for nothing but staring.” Frightened by his tone, the driver fell silent.

After three hours over difficult roads, they arrived in Kabul and got out of the car. Hafeez’s watch read eleven in the morning. Unlike their father, the girls were thrilled, taking in the cars, shops, and bustling people around them. The village could not compare to the city: one was monotonous, the other alive with sights at every turn.

Anisa and Zainab’s attention was caught by an ice cream shop. They paused in front of it. A little girl, standing with her father, licked her icy treat with delight. Zainab was so enamored with the sight that she stuck out her tongue in imitation. Realizing his daughters had fallen behind, Hafeez turned and pulled them along by their hands. Yet even as they walked away, both girls kept glancing back, longingly at the ice cream.

After some time, they reached a tall building, a private hospital. Hafeez led his family inside. An employee at the door directed them to the waiting area, crowded with people queuing to see the doctor.

Hafeez noticed that most of the women were heavy madeup, had carefully shaped eyebrows, and wore no hijabs. While their appearance was striking, it blatantly ignored Sharia law. Hafeez found this unacceptable, certain that his comrades would feel the same. For years, they had fought in mountains and deserts, often without food or water, all for God’s sake and the establishment of an Islamic government. Yet by flouting Sharia, these women dishonored those sacrifices.

Frustrated once more at his inability to correct others due to his superiors’ orders, Hafeez clenched his rifle. He felt a surge of self-disgust for noticing the women’s beauty. Lowering his gaze, he sought refuge silently in God from the devil’s temptation.

After some time, it was their turn. Hafeez and Momina approached the doctor’s office. At the door, he was told not to enter because it was the women’s ward. Hafeez felt a measure of relief — at least here, the clinic observed proper rules. He murmured Subhanallah before returning to sit beside his daughters.

In his heart, Hafeez prayed for his wife’s recovery, hoping they could have another child so he would not be forced to take a second wife. He knew that as a Muslim, he was permitted another marriage, but he disliked the idea. He distrusted women: they were the source of men’s misguidance and corruption in society. Lacking in intelligence, weak-willed, and in constant need of oversight.

Even with Momina it was a struggle. In their seven years of marriage, he was always reminding her to observe the hijab, to restrict her interactions with men, to stay home unless permitted — and to follow countless other rules whose enforcement left him weary. But it was necessary. Stories of women who strayed, who succumbed to moral decay, disobeyed their husbands, and brought corruption to society, haunted him.

Momina emerged from the doctor’s office. Hafeez and his daughters stood immediately.

“What did the doctor say? Can you have more children?” Hafeez asked. His wife handed him the prescription.

“The doctor prescribed this medicine and said that if I still don’t get pregnant, I should come back.”

Hafeez’s irritation was immediate; the thought of returning to Kabul displeased him.

“You should have asked for a stronger prescription so we wouldn’t need to come back.”

“I did,” Momina replied calmly. “But the doctor refused and said that if I want to have more children, I’ll need continuous treatment.”

Hafeez clenched his fist in frustration and slammed it into the palm of his other hand. He had brought his wife and daughters to Kabul half-heartedly, worried that its sinful splendor would tempt them. He now prayed that his wife would be cured by this prescription alone, so that they would not be forced to return.

Fortified by prayer, he took the prescription to the pharmacy, and returned with a plastic bag full of medicine.

Adhan reverberated through the city. Hafeez whispered a prayer, raising his hands to his face. He told Momina that they would eat first, and then he would perform ablution and offer the afternoon prayer.

They stopped at the nearest restaurant along the way. Climbing the narrow iron stairs that creaked underfoot, they entered a large hall. Hafeez looked around. The restaurant was far better than any he had visited in his home province, but that mattered little to him. What stunned him was seeing a man and a woman eating together. He had never imagined such a sight. In all the restaurants he knew, men and women were always seated separately.

He chose a table perfunctorily, and motioned for his wife and daughters to sit.

A waiter approached and asked what he would like. Hafeez, still preoccupied with the couple, asked why men and women were seated together.

“Mullah sahib, this is the family section. Men come here with their families to eat,” the waiter explained. Hafeez then asked about the menu. The waiter rattled off dishes: Qaboli, palow, karaei, dashi, kabab, chayneki…

“Bring four orders of kabab,” Hafeez commanded, not consulting Momina or his daughters. The girls brightened. Anisa nudged Zainab with her elbow.

“What do you want?” Zainab asked.

“How soft are these chairs?” whispered Anisa. Zainab laughed and agreed. Hafeez, agitated, told them to be quiet.

Hafeez eyed the couple suspiciously, wishing his superiors had granted him the authority to question people about their relationships. But only the Vice and Virtue Inspectors were granted such power. In his mind, the man and woman were clearly boyfriend and girlfriend, visiting the restaurant to have fun. The city teemed with people engaging in immoral behavior; he had heard countless stories of their depravity, all in violation of Sharia law. One of the Jihad’s primary objectives, he reminded himself, was to eliminate the licentiousness that foreigners had brought to Afghanistan.

Again, his gaze met that of the woman. Hafeez quickly looked away, uneasy. His wife reached to lift the face veil of her burka. He stopped her with a sharp hand.

“What are you doing? Where is your modesty?”

“May I eat?” she replied quietly.

Hafeez reminded her that the food had not yet arrived and told her to wait. For no particular reason, he angrily picked up the rifle resting on a chair and placed it on another. His suspicions left him with nothing to do but stare at the couple as they ate. Their eyes met his several times. These two aren’t satisfied with each other, he thought. They’re staring at me and my wife. I wish I could hand them both over to the Vice and Virtue Inspectors.

The waiter brought the kabab skewers on a dirty plastic tray. Momina’s stomach growled as she waited for Hafeez’s permission to lift her face veil. Anisa and Zainab also looked to their father, unsure whether to begin eating.

Hafeez scanned the restaurant for a solution. He decided the table by the window was the safest. Lifting the tray of kabab, he motioned for his wife and daughters to follow. At the window, he positioned the four chairs with their backs to the man and woman.

“Now, sit down and lift the face veil of your burka,” he instructed his wife, giving his daughters permission to start eating as well.

Hafeez, however, had lost his appetite, due to the day’s events. He complained that the kabab was bland and tossed his skewer onto the tray after a few bites. He waited impatiently for his wife and children to finish so they could return to the village.

Regret gnawed at him for bringing Momina to the city. He was frustrated at having waited so long for a car and then been unable to respond to the driver’s insult. He despised the lustful driver who had stared at his wife through the rearview mirror, and the couple in the restaurant who had come seeking pleasure. He was exhausted by his inability to curb vice among the people, restrained by his superiors’ orders.

He vowed to himself that even if his wife did not become pregnant again, he would never bring them back to the city. Perhaps it would be better, he thought, to take a second wife instead.

This story was produced as part of Paranda, a writer development program and global network for women writers in Afghanistan and the diaspora, facilitated by Untold Narratives, a development program for writers structurally marginalized by community or conflict, and supported by KFW Stiftung.