A debut novel, set in a real-life Kabul neighborhood, captures the absurdity and distress of life during wartime while presenting a microcosm of Afghan society.

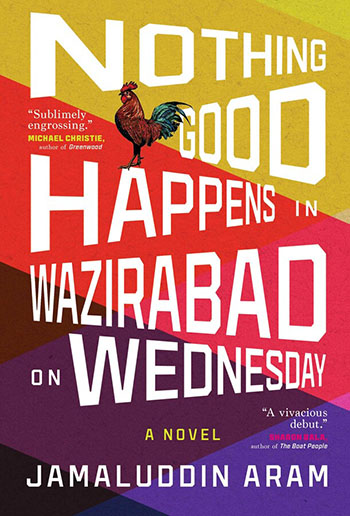

Nothing Good Happens in Wazirabad on Wednesday by Jamaluddin Aram

Scribner Canada 2023

ISBN 9781668009871

Rudi Heinrich

Something beyond war weariness informs author Jamaluddin Aram’s depiction of 1990s Afghanistan in his debut novel. Set in a real-life Kabul neighborhood during the factional struggles that followed the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, but before the Taliban took control in 1996, Nothing Good Happens in Wazirabad on Wednesday features characters who go about their business during the chronic street battles almost as casually as one ducks out of the downpour during a summer rain. We see bonesetters, barbers, storekeepers, and artisans stepping indoors, out of the line of fire, or casually watching the hostilities for any sign of letup. Wazirabad is home to people for whom war and violence are as reliable as the weather, though an occasional stray bullet shatters their complacency. Through an engrossing series of connected vignettes, the author, who hails from Kabul and lives in Toronto, captures the absurdity and distress of life during wartime.

Moral failings and hypocrisy pervade Aram’s Wazirabad, with middle-aged men who had hoped for opportunities and adventure during the war against the Soviets settling into lives of disillusionment, philandering, and drug abuse. Even the three members of the main local militia, who set themselves up as arbiters of justice, are thoroughly corrupt. Aside from serving as a metaphor for the rapacity of the warring parties following the withdrawal of the Soviets and the collapse of the Moscow-backed Afghan government, it is implied that the three are behind a rash of robberies in the neighborhood. One rumor has it that these men, equally criminal and God-fearing, were heard “saying the Morning Prayer on the veranda of the house they had just robbed.”

The vignettes making up Wazirabad are related by a third-person narrator as well as the neighborhood’s characters themselves. Most of the characters are referred to by their profession: the Bonesetter, the Baker, the Electrician, the Bucktoothed Tailor, and so on. Aram’s descriptions of the neighborhood stir with quotidian scenes, details of which a casual visitor might overlook. The Bonesetter grinds herbs and reads poetry to his cat. Aziz, a 15-year-old disturbed by dreams of home-invading marauders, reinforces a wall with glass shards to guard against the phenomenon. Seema, his little sister, sells scorpions to the hashish-smoking militiamen, who seek a more potent high. A prancing rooster makes his rounds to the neighborhood’s hens with an uneasy urgency, getting what he can. The rooster is emblematic of the resigned desperation of people living in a place where things can suddenly collapse into violence and instability.

In honest but sentimental fashion, the author highlights the pieties of a society that is traditional, superstitious, and hopelessly banal. One gets the impression that unceasing political instability and infighting are not so much the problem. Wazirabad’s residents are little removed from folk traditions, their thoughts shot through with the fear of curses, a belief in magic, and an unshakable faith that dreams have meaning.

Indeed, dreams, angels, and the spirits of the departed are a feature of the neighborhood. The Prophet Mohammad’s image is supposedly seen by a muezzin in a purplish soap stain in a window of the neighborhood mosque. The muezzin whispers to himself: “A miracle doesn’t have a sign on its head shouting, ‘Miracle.’ This is it.” Afterwards, the Prophet himself appears in a dream had collectively by all the neighborhood’s residents, wherein he visits Wazirabad to inspect the window supposedly bearing his image. Sikandar, a young man who dozes off while visiting his mother’s grave, beholds the dead conferring over glasses of tea; his mother is there, too, and she tells him that the afterlife isn’t bad, as there is no longer anxiety about anything that can kill you. Dreams and portents, as well as individual ailments, are brought before the Bonesetter for interpretation and relief; he is given more reverence than the district’s sole medical doctor, who does not seem to know what to make of the behavior and superstitions of the residents.

Intriguingly, there are few puritans to be found in Wazirabad, and no longing for anything resembling religious stricture of a kind that would emerge later with the Taliban. An impoverished widow who offers sex so that she might make ends meet is the talk of the neighborhood. But even as she is hissed at and branded a curse on the place, many of the men indulge in her services. Another woman asserts her independence by angrily leaving the family and getting married without the male members’ consent. Yet another woman, one who is unhappily married, takes a lover under the guise of friendship.

One wonders at the dynamics of the novel’s urban setting. Would the choices these women make have gone unpunished in Afghanistan’s countryside, where the murder of daughters and wives to guard familial honor is longstanding practice? It might be encouraging to any readers who see a foreshadowing of an honor killing that the expected murder by male relatives never takes place. The wrath of fathers and brothers, while ugly enough, does not escalate to the point of butchery.

That said, there are red lines, and transgressing them can prove fatal. Malem the Calligrapher, an erudite teacher, is murdered for reading heresies propounded by freethinkers — “he said something to the effect that in essence loving a man or woman was the same as loving God” — and, worse yet, teaching them to his students. His murderers are the three militiamen-cum-thieves. For all the resentment they generate, on this occasion the trio is praised by some of Wazirabad’s residents. These goons with guns who extort and even rob the populace as a matter of course are nonetheless looked to for maintaining some kind of order, however raw.

Elsewhere in the story, a cleric suggests that another man murdered by the militiamen for his transgressions might have found refuge in the mosque, as his pursuers “wouldn’t have dared to enter the House of God.” Yet the mullah may be wrong. The congregants at his mosque respond by saying, “[D]on’t you know the war has changed people, particularly those who fought in it? They have lost their fear of death and of God, and they have power. They are the ones with guns.”

Admittedly, Wazirabad does not situate mid-’90s Kabul within Afghanistan’s historical trajectory. The reader would have benefited from a bit of contextualization. This is especially true of vignettes whose poignancy or pointedness lies in the fact that they depict realities different from those that prevailed under the recently departed Soviets or that would come to prevail under the fast-encroaching Taliban.

Wazirabad’s neighborhood gossip and its street scenes will have to compensate for this shortcoming. For the most part, they do. Though the setting is Afghanistan’s capital and its most populous city, Wazirabad is a kind of village. The characters share an intimacy that Aram renders with confidence and care. There is also the building of a suspenseful inevitability in the run-up to certain characters meeting their destiny and/or doom. The action never leaves Wazirabad’s precincts, with larger events referred to only as “the fighting.” Yet that is generally not a problem; Aram presents the reader with a microcosm of Afghan society.

A thoughtful and well-constructed review by Rudi Heinrich. An excellent review.