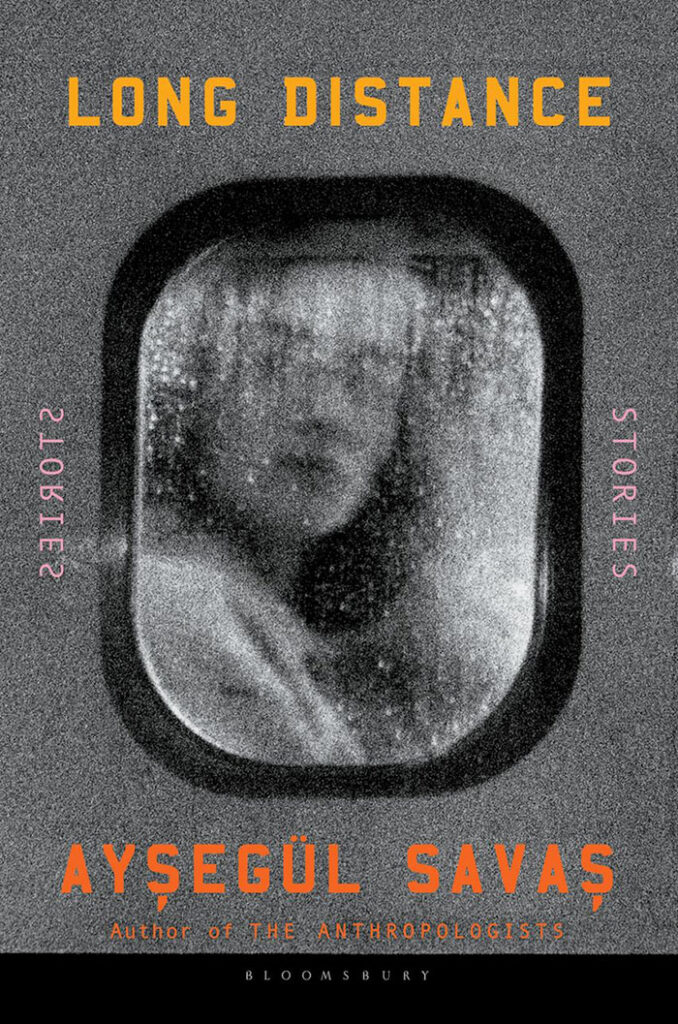

In the new story collection by Turkish writer Ayşegül Savaş, cities — Paris, Rome, Istanbul — become the characters.

Long Distance by Ayşegül Savaş

Bloomsbury Press, 2025

ISBN 9781639733101

Ayşegül Savaş, author of the recently released compilation of short stories, Long Distance, is a master at eloquently weaving cities as a character into her fiction. Her approach, exhibited equally in her stories and longer fiction White on White, Walking on the Ceiling, The Anthropologists, teeters between explicit mention of a city, grounding the story in a specific place, or not mentioning the city at all. Even in the latter case, Savaş’ characters are so affected by their locations that it’s impossible to regard them as anything but fellow characters, used to tease out the protagonist’s arch.

Born in Turkey, Savas, who subsequently called a series of places “home,” currently resides in Paris, and writes in English. Perhaps these intimate moments spent abroad are the foundation of why cities are often a source of tension in Savaş’ protagonists, adding a layer of understanding to their journey, particularly in their respective phases of life. A city is never accidental; it is a tool used to color the past, present, or future of her characters. How that character operates within that space sets the tone for how they perceive themselves and how they operate within the context of the story. A city has the power to tell an infinite number of stories. Does Paris mean a new beginning? Istanbul, a bittersweet step into family history? Rome — somewhere in between?

Over the thirteen short stories comprising Long Distance, Savaş transports her readers into the lives of her female protagonists, consumed with an array of refreshingly honest human conditions. Written over different life stages and places of residence during Savaş’ career, there is a story for everyone; some, remembrances of the past, others, a warning for the future. Savaş’s characters face head on themes of grief, love, jealousy, and mourning, all set against a backdrop of a city sometimes defined, sometimes left open, presumably to avoid manipulating the biases of the audience but giving just enough to taste their surroundings.

Rome

The eponymous story of the Long Distance collection was first released in The New Yorker, in 2022. I serendipitously read it late in 2024, just a few months after moving to Rome. Never underestimate the power of works of art to appear at a time when you need them most. Like Lea, Savaş’s protagonist, I too had just started to call Rome my home, becoming fiercely protective and particular about an adopted city now an extension of my own identity; a reflection of myself.

Lea, a postdoctoral fellow, is in a long-distance relationship with her partner Leo, who is based in California. Their relationship is fresh; a romance unfolding from an intimacy formulated during their time apart rather than together. During Leo’s first visit to Rome, Lea is anxious to maintain her persona, constructed during their cross water communications. For Lea, Rome represents a departure from reality, from her life back “home” in California. Rome offers a chance for Lea to live out a fantasy of being a certain type of woman, in a certain type of relationship, but how sustainable is this reality?

“She wanted to portray another version of herself; a young woman in Rome, enchanted in life.”

Her efforts to show Leo her version of a good time in Rome (e.g., visiting the Colosseo, eating from specific gelato shops) surfaces the tension between her internal expectations and the external reality of their relationship, unfolding into a series of miscommunications between a couple seeped in uncertainty over their budding romance. “Long Distance” is a tragically candid depiction of the dissonance between what we want to say vs. what we actually say.

Paris

“The Room” dips a toe into both of Savaş’ operating worlds — the exterior and interior. The protagonist, Leyla, like so many before and after her, has come to Paris to be a writer. Yet after an initial period of stimulation inhabiting the city with fellow artist roommates, she yearns for solitude.

Paris is still an unreal city to them all, with the elusive promise of inspiration, though it requires confirmation to believe this, when their lives can just as easily seem to be floating without direction.

Leyla rents a chambre de bonne — erstwhile servant quarters now listed as a working studio — from an elderly couple who seemingly turn a blind eye to Leyla’s intention to illegally live in the space. As Leyla begins to find comfort in her coveted room, Savaş’s locations graciously fold into the other. The lure of Paris metamorphoses into the lure of a Virginia Woolf-like “Room of One’s Own.” Is it Paris, her own room, or a combination of both that makes Leyla feel whole? In Leyla’s world, one cannot exist without the other; it is the symbiosis of the city and room that afford her the autonomy to come into her own. Vis-à-vis Leyla’s studio, Savaş quietly captures that uniquely specific moment in a younger adult’s life just after the post-college roommate phase, where even a meager inkling of personal possession holds the promise of a fulfilled future.

But what matters to her is that she feels welcomed in her own life, and free. She is surprised that it’s been this simple — making herself useful enough to be paid; living in a beautiful place where she can close the door and be alone… but Leyla doesn’t want to be swept away from her life, from the room where her thoughts have only just begun to settle.

“Layover,” also set in Paris, takes a different point of view of the city. Though Lara, Savaş’ protagonist, is not native to Paris, Savaş differentiates her from the wide-eyed, hopeful, younger Leyla in “The Room.” A long-time resident, settled in her ways and routines, accepting that she will never conquer the city’s unending attractions, Lara feels like a continuation of Leyla. Perhaps Lara represents a future Leyla, one who has spent time reflecting on her younger self, intentionally constructing her new identity separate from her life back in Istanbul.

The city was full of such places. Their inaccessibility had charmed her when she first moved here, as if it were an invitation to explore, to make the city her own.

When an old childhood friend from Turkey, Selin, visits her while on a layover, Lara sets the tone of a cool, jaded Parisian juxtaposed against Selin’s earnest excitement of the city. Through Lara, Savaş paints a portrait of a character whose carefully applied enamel over her identity begins to chip, revealing her insecurities within. When old friends drift away, we have the natural tendency to view that friendship from the perspective we left it at. Savaş displays the mildly cringe-worthy complexities of this dynamic as Lara almost infantilizes Selin — treating her to a classic Parisian breakfast, assuming her ignorance of Lara’s city, judging Selin’s professional and romantic decisions. In typical Savaş fashion, she slow drips her characters’ layers until the very end, when one piece of information from Selin flips Lara’s perspective upside down. Is it possible to detach yourself from your past self? While Paris signifies a new beginning for Leyla, Paris is a hideaway from Lara’s past.

Istanbul

Set in Istanbul, “Freedom to Move” is a multigenerational story centered around an unnamed granddaughter who, living abroad, comes to meet her aging grandfather in Istanbul. Like “The Room,” Savaş again plays with two worlds– the vastness of Istanbul contained within the intimate context of a Beşiktaş apartment, to which the grandfather is largely confined.

Savaş introduces a second location into the mix through the grandfather’s Georgian nurse, Ketevan, and her daughter, Natela. Savaş’ choice to name the nurse and daughter but not the other characters deliberately contextualizes both the city of Istanbul and apartment to be viewed through the lens of an overlooked minority service population. Aside from the granddaughter’s loose mention of the neighborhoods she revisits on her short visit, the grandfather’s past travels around the Black Sea, and future trips to seaside Ayvalik, it’s not Turkey but Georgia that dominates this story. Ketevan and Natela serve Georgian food and wine and speak longingly of returning to their homeland. The very presence of this competing location creates tension within the granddaughter. A tension fueled by guilt over her grandfather’s predicament, which, like Ketevan’s request to visit her homeland, she ultimately chooses to ignore. Savaş nudges her readers to question who is entitled to freely move locations and what mechanisms do we employ to hinder that freedom?

“I’d more or less decided that I wasn’t going to mention Ketevan’s request to my father. No doubt it would only anger him and once again, and I didn’t want to spoil our short time together. Anyway, I was in no position to defend the woman, to explain her wish to see her husband and son.”

In “Freedom to Move,” Istanbul’s significance splits into pieces, holding different meanings for each character. For the protagonist living abroad, Istanbul equals guilt for not spending enough time with her family and ailing grandfather, as well as guilt over her privilege to be able to jump between multiple worlds. For Ketevan and Natela, Istanbul is equally the savior and entrapper, enabling them to support their family back in Georgia, who they are inevitably hindered from seeing.

“Twirl,” though set in an unnamed city, also serves as a vehicle for an Istanbul background, painting a more vivid picture of the city than one that is set there. By cleverly omitting the location of her protagonists, Savaş sets the scene for her unnamed protagonist and secondary character, Zerrin, both who are of Turkish origin. Though in different life stages — the protagonist is younger and single and Zerrin is married with a small child — the two develop a friendship through their common language and culture, meeting weekly, and reminiscing vividly over memories of time spent in Istanbul neighborhoods. In Zerrin, Savaş finessely constructs a portrait of a culturally displaced woman who is unable to break free from a romanticized past and youth in her homeland. So much so, that it’s easy to forget “Twirl” is not set in Istanbul, but in an unnamed city.

‘I used to be just like you,’ she often told me, relating anecdotes from her student years in Istanbul, when she would be out all night in Cihangir, spend whole days visiting bookshops.

For Zerrin, Istanbul is a lifeline, a means of escape from what she perceives as an uneventful reality. “Twirl” is a punch to the gut, as it is a reminder of the subtly haunting ways we cope with an unautonomous reality and the stories we tell ourselves to persist, irrespective of our physical location.

•

You’ll find these stories and others in Long Distance. Below you’ll find a few of Savas’ favorite spots in the aforementioned cities:

Savaş’ Paris:

- The Luxembourg Gardens

- Sunday morning at March d’Aligre

- The banks of the Seine

Savaş’ Rome:

- Walking around Monti

- Palazzo Massimo

- Pecorino restaurant in Testaccio

Savaş’ Istanbul:

- Arkeoloji Muzesi

- Breakfast in Çengelköy

- The Kadıköy Ferry

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)