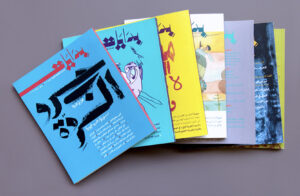

Shubeik Lubeik, a graphic novel by Deena Mohamed

Pantheon Books (Penguin Random House) 2023

ISBN: 9781524748418

Katie Logan

In the summer of 2019, Egyptian comics artist Deena Mohamed led a workshop on comics translation as part of London’s biannual Shubbak Festival, in which she shared with the participants that her already award-winning comics trilogy, Shubeik Lubeik, would be published in her own English translation in 2021. In a nod to the workshop’s preoccupations, she also explained that she had yet to settle on an English title for the project. The trilogy constructs a world in which wishes as material objects are bought, sold, and used to varying degrees of effectiveness; though Shubeik Lubeik might be most closely translated as “your wish is my command,” the change robs the phrase of its playful sonic qualities and its Arabic literary history.

The world has changed many times over since that summer of 2019; those of us eagerly anticipating Shubeik Lubeik’s arrival on the U.S. literary scene had to wait an additional two years past the planned 2021 publication date. And when the English-language Shubeik Lubeik finally did arrive in January 2023, courtesy of Pantheon Books, it showed up wearing its original title.

It would be difficult to discuss the content of the English-language Shubeik Lubeik without first marveling at the care with which Mohamed has shepherded this project across linguistic and cultural borders. From the outset, it’s clear that Mohamed intends to confront English-language readers with the ghost of the Arabic original. In addition to retaining the original title, the striking hardcover is bound on the right, and the inside cover greets readers with the following inscription: “This book was once in Arabic, so it is read from right to left. You are now at the beginning” (the back cover offers a similar note-cum-admonition, telling readers habituated to reading from left to right that “you are now at the end”). While Cairene signs and billboards remain in their Arabic original, Mohamed includes footnotes for key information and for building a jocular familiarity with the audience; for example, an early footnote explaining “yalla” acknowledges that it’s “a word you’ll be hearing a lot.” In an article for Big Issue, Mohamed writes that this unconventional approach to translation — at least to those who don’t read manga — “opened up” the process for her.

Mohamed’s expansive, playful, yet rigorous approach to translation mirrors the expansive, playful, yet rigorous world of Shubeik Lubeik. Both narratively and visually, this trilogy is a knockout. Detailed storytelling flirts with dystopia, fantasy, psychological drama, domestic sagas, and political intrigue. As with other comics artists publishing in Arabic or in Arab-Anglophone contexts, including Leila Abdelrazaq, Iasmin Omar Ata, Magdy El Shafee, and important collectives such as Samandal (Lebanon), TokTok (Egypt), and Maamoul Press, Mohamed engages the surreal, the magical, and even a bit of noir as she constructs a world where the logic of wishes co-exists alongside contemporary Egyptian bureaucracy. Each of these artists has described the way in which recourse to the medium of the graphic novel as well as genres that engage the fantastic allow them to narrate histories and circumstances they would otherwise consider un-narratable. Recounting her experience drafting the black and white graphic novel Baddawi (Just World Books, 2015), Leila Abdelrazaq explains that in narrating her father’s life, the visual language of comics allowed for a range of representational options: “Because I will never understand what it’s like to grow up in war and to grow up as a refugee . . . I resort to more surreal imagery that gives more of a feeling and implies something than trying to replicate something exactly.”

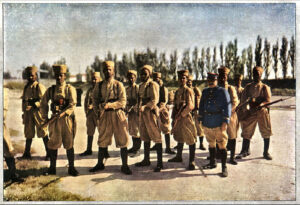

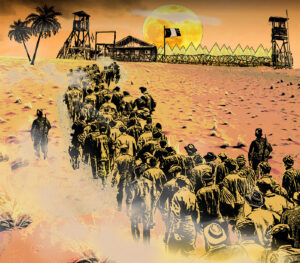

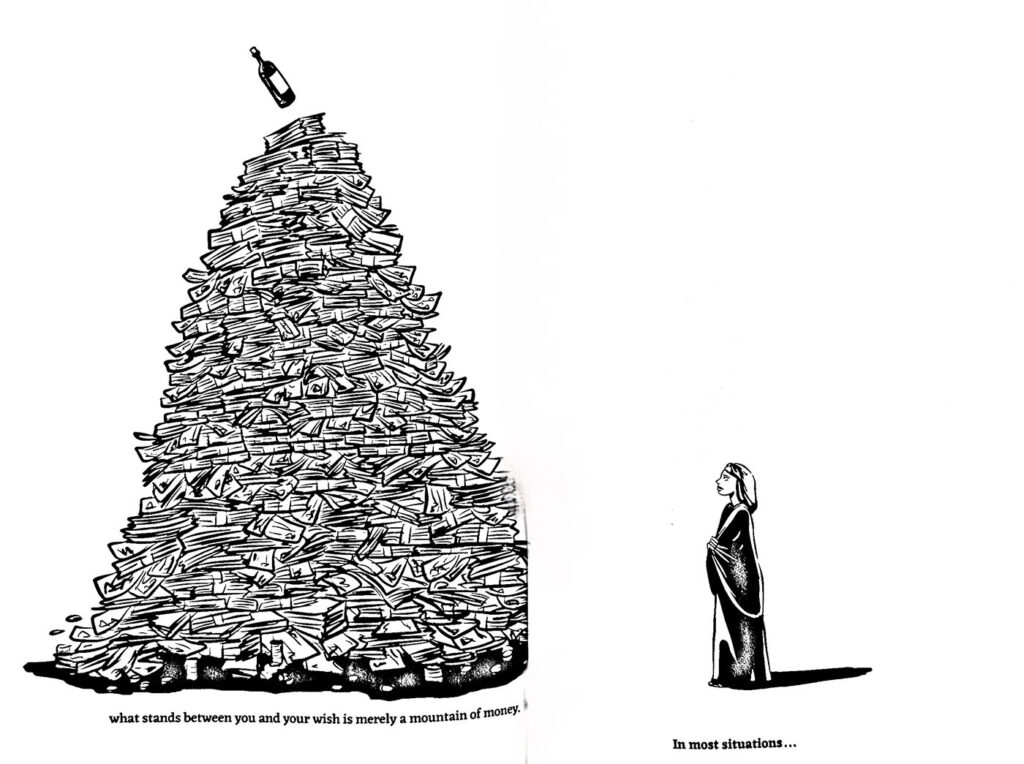

Similarly, Mohamed’s efforts to narrate day to day life in contemporary Cairo benefits from the way she introduces wishes as a commodity that people buy, sell, trade and use. In her deft hand, fantastical wishes become the mechanism through which the reality of one’s circumstances is revealed. In Shubeik Lubeik, the wishes characters make throw into relief the extractive, exploitative, racist, and misogynistic practices that swirl around the trilogy’s characters. Readers will not be surprised to learn that the mining for the “raw material” of wishes occurs primarily in the Middle East and Africa, while the refining, marketing, and profiting off these goods takes place in Europe and the United States. Additionally, wishes are sorted into classes based on effectiveness, governed by a complex global bureaucracy that exacerbates pre-existing wealth disparities, and morally censored by religious authorities and activist groups.

Mohamed shapes this world so thoroughly that, for the reader, each discovery of a new stakeholder, a new regulation, or a new wrinkle in the wish system is simultaneously an intellectual delight and a sobering reminder of the way even generosity and community are conscripted into neoliberal economic orders. For example, when a former wish charity must turn down donated wishes, one character explains:

People [have to] donate money, and then those funds are used to buy subsidized wishes that the government provides at a discount . . . Those subsidized wishes are actually a requirement for all countries who signed the second wish equality amendment of ’94 . . . and based on that, we qualify for the public-interest wish loans from the International Wish Federation.

Over the course of the trilogy, readers follow three “first class” wishes, all of which initially languish at Shokry’s kiosk. The wishes — whose provenance is revealed in compelling fashion in the third section — are a proverbial albatross for Shokry. To get rid of the wishes, he offers his customers major discounts, which only raises suspicions about their quality. It’s not a big revelation to say that each section of the trilogy follows a wish to a new home, although the form each wish takes and the buyer’s decision-making about how and whether to use it is too well-plotted to spoil here.

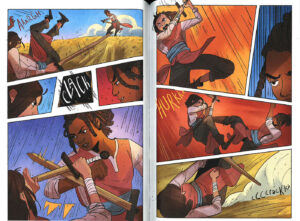

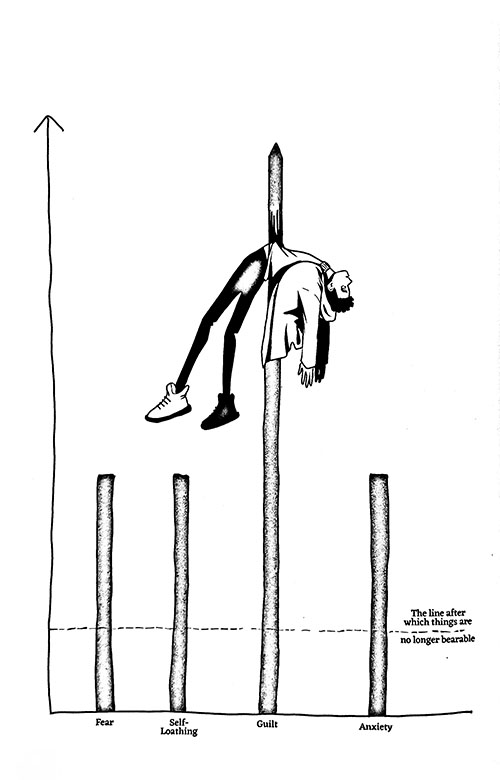

Part One features Aziza, a grieving widow whose wish acquisition throws her into the carceral underbelly of Egypt’s wish institutions, making for a dystopian plotline that rivals Basma Abdel Aziz’s The Queue in its imaginative critique of bureaucracy’s violences. In Part Two, readers follow the wealthy, gender non-conforming college student Nour, who majors in “Wishful Thinking.” Nour impulsively buys a wish to cure their depression only to fall into deeper despair while figuring out what to wish for. Mohamed’s efforts to convey Nour’s inner turmoil rely on creative charts used to devastating effect, as in a full-page panel where a particularly spiky bar graph impales Nour on their own guilt. Part Three delves into Shokry’s backstory as well as his determination to share the last of the three wishes with a friend and customer dying of cancer. In this section, Mohamed’s light comedic touch and gift for plot shine through, as resonances, reunions, and surprising twists abound.

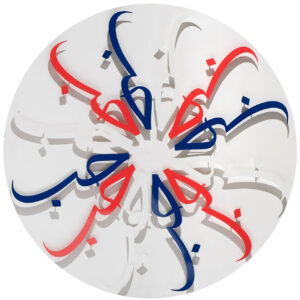

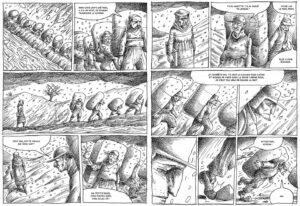

As Mohamed balances a range of narrative tones, her arresting images take on a cinematic quality. It’s rare to think of black and white images as “vibrant,” but Mohamed’s are precisely that. And her crafting temporality through a visual medium is a masterclass in pacing. Even as Aziza takes years to purchase her wish, readers follow every odd job, every pound saved, every ounce of effort in her tired hands, all through a heart-pounding montage sequence. And when Shokry learns a secret that changes everything, Mohamed uses multiple panels to register the complex reactions flitting across his face. Even written text becomes an art form, as dialogue romps across the page and djinn emerge in the form of intricate calligraphy.

For Shubeik Lubeik, myth and myth-making is a form of power. Myth-making is about consolidating narrative and origin stories such that they gain traction with each new listener. As the comic reveals time and again, the strength of those narratives often obscures the exchanges and dynamics under the surface, which don’t always cohere in a neat linear structure. Shubeik Lubeik asks readers to question the power of the origin story. As each part of the trilogy complicates our understanding of what it means to begin or to create change, the focal points we perceive as origins come apart at the seams. Seeking a clear point of origin makes it harder, not easier, for Nour to accept and treat their depression. By contrast, Shokry is committed to an origin story that defines wishes as inherently sinful, only to have his beliefs challenged by young Egyptians researching connections between religious leaders and wish corporations.

Notably, Shubeik Lubeik does not conclude in tidy resolution. Rather than lay the groundwork for a sequel, the trilogy’s unanswered questions seem to tend once again to toward expansiveness. What Mohamed has constructed here is not simply a new myth to replace the old, but rather an open-ended world that invites readers in, challenges them to stay and think awhile, and then ushers them back into their own, wish-less world, where they might pay renewed attention to the structures of power and global exchange all around us.

For further comix reading:

Rushda Rafik, An Interview with Graphic Memoirist Malaka Gharib

Aomr Boum, “Why COMIX? An Emerging Medium of Writing the Middle East and North Africa

George Jad Khoury, Rebellion Resurrected: The Will of Youth Against History

Sherine Hamdy, Women Comic Artists, from Afghanistan to Morocco