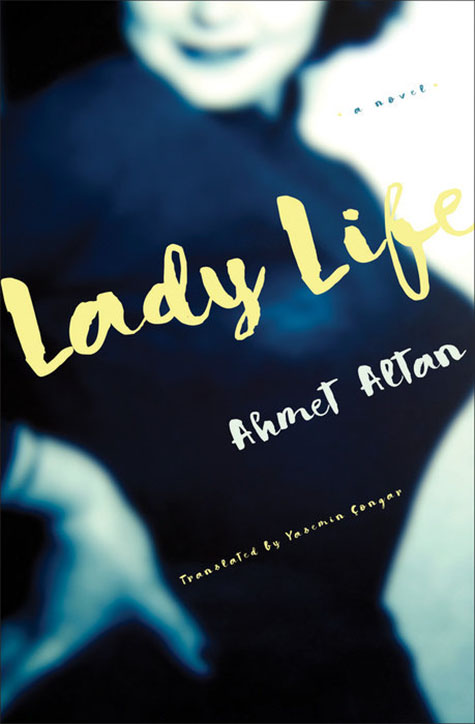

Kaya Genç’s review of Lady Life first appeared in the Los Angeles Review of Books and is published here by arrangement with LARB.

Lady Life, by Ahmet Altan

Penguin

ISBN 9781635422887

Kaya Genç

IN 2016, Ahmet Altan, one of Turkey’s leading novelists, fell victim to the Turkish government’s post-coup purges. Cops detained Altan at his home in Istanbul, drove him to a police station (and confessed to being fans of his books on the way), and locked the author up in a basement prison populated by hundreds of shocked dissidents. Altan had to wait two years before a judge handed him a sentence: life in prison without parole. His crime? Attempting to topple the government using “subliminal messages.” Fifty-one Nobel laureates, including Kazuo Ishiguro and J. M. Coetzee, signed an open letter calling for Altan’s release.

Luckily, Altan got out, but only after spending four years and seven months inside a cell. He was 71 when freed in April 2021. In captivity, his fierce mood didn’t diminish, and he wrote three books: I Will Never See the World Again: The Memoir of an Imprisoned Writer (2019); Zar, a yet unpublished historical novel; and Lady Life (2021), a novella that documents the widespread purges that began in the wake of the failed 2016 coup and subsided with the opposition victories in 2019’s mayoral elections. I Will Never See the World Again was translated by Yasemin Çongar and published by Other Press in October 2019, and now the same duo have brought us an English translation of Lady Life.

Lady Life may trigger its Turkish readers. I identified with its hero, Fazıl, an impressionable college student whose life goal is to become a literary critic. He reminded me of myself in college and what I saw with my own eyes in the late 2010s. Fazıl’s problems begin when his father goes bankrupt overnight after a “major country” announces it will stop the import of tomatoes from Turkey. This is based on reality: in January 2016, Russia imposed a tomato-import embargo on Turkey after an Islamist militant aligned with Turkish soldiers downed a Russian fighter jet in 2015. With thousands of acres of his land turned into a “scarlet-colored dump,” Fazıl’s father loses all the money he had invested in the crop. The following day, a stroke delivers the bankrupted man to the grave.

Feeling like he’s “free-falling in an unfamiliar void,” Fazıl has no idea what he is falling toward. In the course of the book, he finds out he is not alone in this free fall. Lives are changing overnight everywhere in Turkey, a country driving headlong toward economic collapse and pervasive authoritarianism. The days of luxury are over for Fazıl and the Turks, who, after enjoying the benefits of neoliberal capitalism for years, are now being damaged by its demise.

One week after his father’s funeral, Fazıl boards a bus to Istanbul and heads to Pera, the city’s refuge for the politically and sexually marginalized. He finds “a room for rent on a street of dive bars […] in a six-story building from the nineteenth century.” Purple wisteria climbs the face of the building, which houses a non-functioning “wooden elevator […] in its antique cage.” Fazıl sells all his clothes and books; even his laptop and mobile phone are gone.

Altan sketches the daily life of Pera in attractively drawn vignettes. As Fazıl sits on his room’s small balcony, we survey the cobblestone street with him:

A cloud of anise, tobacco, and fried fish drifted up. There were sounds of laughter, whistles, joyful whoops. It was as if once you entered that scene, anything that happened outside was forgotten, and a transient bliss enveloped everyone. I watched from afar that fleeting vivacity in which I could no longer take part.

In the boarding house, Fazıl befriends Gülsüm, a cross-dresser; “Poet,” a young dissident who edits an opposition magazine; and “Mogambo,” a handbag seller of African origin. To support his education, Fazıl finds part-time work with a casting agency. After his classes, he heads to a studio to participate as a spectator in a program premised on filming dancing people on a podium. Before the shoot ends, Fazıl notices a feminine face on the screen: “[It] had a teasing joviality about it, as if she were getting ready to crack a joke. She seemed on the brink of laughter.” Infatuated with the 40-something woman in the honey-colored dress, he accepts her offer to share a meal.

This leads to a friendship with benefits. Hayat Hanım (“Lady Life”), whose life philosophy is carpe diem, seems like a character from a medieval romance. The narrator rolls the name around in his mind, thinking, “Hayat Hanım, I repeated to myself in all the languages I could: Hayat Hanım, Lady Life, Madame la Vie, Signora la Vita, Señora la Vida.” Her knowledge of life comes from documentaries: she knows, for example, that “some wood frogs completely freeze in winter, fall and break their icy bodies like a piece of china, but come back to life and are healed in the summer,” and “that leopards fight with baboons.” When she learns that Fazıl studies literature, Hayat says she gets bored with novels: “I already know the things novelists write. What I know about people is enough for me.” She has “never heard of Faulkner, Proust, or Henry James.”

Amid poverty, loneliness, and desperation, Fazıl notices the emergence of a terrifying group of pro-government thugs. These bearded men, who carry baseball bats to beat dissidents on the streets, are fashioned after the notorious sopalı vigilante groups, a trademark of Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II, who organized armed Kurdish groups against Armenians in the 1890s. Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who adores Hamid, resurrected sopalı during the Gezi protests in 2013. From a 19th-century balcony in Pera, almost a replica of Fazıl’s, I watched men with sticks beat rebels on the streets in July of that year. Fazıl watches as they attack an “art gallery in broad daylight, beat everyone inside, saying You can’t drink liquor here, and destro[y] the artwork.” Expressing their hatred for “all kinds of entertainment,” these men “hated everyone who wasn’t like them.”

Gentrification of Istanbul delivers another blow to Fazıl. The arcade where he buys secondhand books now resembles “a patient on his deathbed.” The bookseller informs him that “[n]o one comes here anymore,” and so “[t]hey will soon demolish the building anyway.” For an aspiring literary critic, this is terrible news: “People had abandoned books. I never thought this could happen. No matter what, there were people who would always love books, but they weren’t there today.”

Fazıl’s new classmate from the literature faculty, Sıla, shares his pessimism. She’s a playful bookworm who, in their first meeting, asks him: “If you could have written any fifteen pages of literature from the whole of history, which fifteen pages would you choose?” Fazıl notices that Sıla’s test resembles the riddle of the hat in Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince: only those who notice the drawing of the hat is actually the image of a boa constrictor swallowing an elephant can be trusted: “We would become friends if I gave the right answer; if not, she would lose all interest in me.” Eventually, his response — the “Time Passes” chapters in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse — impresses Sıla enough to make them lovers.

While Fazıl’s difficulties are financial, Sıla’s come from being a member of a family politically demonized by the government. Thanks to her father, once the proprietor of a major company, she spent her childhood in an orchard-covered villa. But after a minor partner in the firm is arrested on charges of “conspiracy against the government,” her world turns upside down. Authorities, spotting an opportunity, detain her father and confiscate all their savings before taking over his entire business. With a single suitcase, the family spends the night of the raid at a park nearby: “That morning we were wealthy, even at dinnertime that day we were wealthy, but by midnight we had become homeless, penniless paupers.”

This Cinderella scenario, where their posh lives turn into a pumpkin at midnight, leads Sıla’s father to work at the wholesale vegetable market as a middleman, buying and selling bruised fruits and vegetables. His daughter’s only hope now is her cousin Hakan, who is in Canada for a year on a scholarship. She plans to join him there.

At the literature faculty, one of their professors, Nermin Hanım, stylish in black skintight jeans and red stilettos, peppers her lectures with truisms. “Literature can’t be taught,” she proposes. “What I will teach you is what one badly needs in dealing with literature, and that is literary courage. Don’t try to exist by repeating other people’s phrases. Be brave. Literature takes courage; great writers emerge from among those who write with courage.” It’s unnerving and saddening to watch Sıla and Fazıl search for the meaning of their lives in the works of Flaubert, Chekhov, and Tolstoy in a culture where loyalty to an autocrat has become the sole remaining public value.

Altan writes voraciously about sex. “I couldn’t stop touching her,” Fazıl says of Lady Hayat. To him, she is a “mythological goddess whose name was yet to be added to the dictionary.” Although she is not classically beautiful (Altan recalls Proust’s words while describing her: “Let us leave pretty women to men with no imagination”), her body casts an arcane spell on him. He has to touch and hold her to feel alive.

But soon reality intervenes, smashing Fazıl’s dreams of a life devoted to Joseph Conrad and cunnilingus. Cops raid the boardinghouse one day before dawn, taking away two guys who live on the first floor who posted critical articles on Facebook. Fazıl describes his plight through an unsettling simile: “It was as if we were sitting in the palm of a giant who, whenever he wanted, could make a fist and crush us in it.”

To read Altan’s novel is to observe, from a remove, the shifting moods of a young man undergoing a spiritual crisis. Lady Life’s unfussy prose reminded me of Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf. Altan’s young characters are also at intersections of their lives, aware that a misstep may prove too costly. “My feelings changed rapidly,” Fazıl muses, before coming up with an image that chilled me in the wake of the recent devastating earthquakes in Turkey: “I resembled a building whose foundation had cracked in a major quake, I thought, so that things in that building were no longer safe and reliable.”

But it is Sıla’s disintegration that is most upsetting. When Fazıl buys her 100 grams of orange chocolate truffles and two marrons déguisés — a luxury she had been deprived of for long — she is brought to tears: “I can’t stand that a hundred grams of chocolate is making me so happy.” A more considerable humiliation for her is watching her family’s former driver, Yakup, rise up the ladder of the new Turkey as a contractor, making millions thanks to his older brother, the deputy chief of the district’s ruling party. Sıla is terrified that party members will take her only remaining belongings — her plans for escape — yet they take something of greater value: her father. His lawyers are arrested, too. When Sıla and Fazıl visit the large, fortress-like police department, a cop holding a machine gun tells them off in a threatening tone. They wait four days, taking turns to go home and change their clothes. When the father finally emerges, he has a scraggly beard and a “pale face, sunken eyes. His clothes were dirty.” Inside, says the forlorn man, the police had “made [him] sign a paper declaring [he] won’t sue them to take back [his] property.”

Another morning, police raid the room of Fazıl’s friend Poet. He escapes to a balcony, where Fazıl sees him in his “flimsy shirt” before their eyes meet: “I saw the reflection of clouds on his face. I stretched my hand out to him, but we were too far apart. Suddenly, he pushed the wall he was leaning against and let himself go.” Now burdened with responsibility and guilt, Fazıl devotes himself to dissident publishing, a choice that lifts the lid off life in Turkey for him.

Thanks to his new editorial post, Fazıl can see, in microscopic detail, the truth of his repressive country. He finds “an entirely disparate mode of existence […] a life that resembled what people referred to as Hell.” He notices “fathers […] committing suicide with their families, sharing cyanide with their wives and children” out of sheer desperation; starved people setting themselves on fire in public; hungry children begging on the roads; “workers […] sacked with no severance pay.” All of these stark incidents were “being kept under the cover of a terrifying silence. Daily papers, TV shows, newscasts did not talk about these things. People were free to set themselves on fire because they were starving, but it was forbidden to talk about these acts of suicide.”

Altan shows, with remarkable skill, how the smallest details of life are saturated in a creeping autocracy. When the arcade housing Fazıl’s beloved secondhand booksellers is replaced by a “mud-filled ditch,” he feels violated:

I had come to this arcade many times over the years, browsing the shops and inhaling dust and the smell of old paper, bought many of my favorite books here, observing on their pages the traces left by their owners before me, imagining what might have gone through their minds when they read those paragraphs, leaving my own traces.

He says that it feels as if the gentrifiers “had entered [his] home at night, destroyed everything, written threats on the ruined walls that they would be back. That’s how it felt to [him].” In academia, too, oppression prevails. Nermin Hanım and Kaan Bey, Fazıl and Sıla’s favorite literature professors, are arrested for signing a peace petition: “All fifty of the professors who signed it were taken from their homes before dawn.”

All that horror, those of us who refuse to leave Istanbul well know, is based on reality. As the country is remade for the likes of Yakup, the former driver of Sıla, the sensitive and the creative lose their wealth and freedom. Yakup hires a driver who shares his name, and by shouting orders to another Yakup, the newly rich man presumably feels he is taking revenge for his own past — a form of resentment that Islamism’s reign in Turkey promotes and legitimizes. “If one has commercial sagacity making money is easy-peasy,” says Yakup, and thinks, “this country has never been in better shape.”

Fazıl and Sıla agree there’s no future in Turkey for them. Everything had been shifting over the past decade, but now it seems “as though the pace of change ha[s] increased.” They aren’t unlike frogs being slowly boiled to death. Altan writes beautifully about the mood surrounding departure and self-exile, that hardest of decisions. Fazıl conjures an “image of a ship […] a large vessel getting ready with the tiniest of maneuvers for its final hawser to be withdrawn in order to leave the dock.”

Yet Istanbul refuses to let go. Wandering the city, Fazıl notices the warm weather, the blossoming trees, the playful clouds passing over the sky. “The cool smell” of the Bosphorus engulfs him. At the same time, Fazıl is torn between the two women in his life. Lady Hayat, for whom “[t]here’s nothing to understand” and “[w]hat you see is what you get,” urges him to leave Turkey promptly: “I wouldn’t be able to live with myself if you ended up in prison.” With Sıla, who enjoys “getting into long arguments about all kinds of things” with him, a life elsewhere together is an attractive proposition.

Will they leave or not? Does it matter? Suffice it to say that the book’s ending packs a punch. Closing Lady Life, I imagined Altan writing the final words in prison, presumably home to hundreds of Fazıls who couldn’t afford to leave: “I am waiting. I am here.