Select Other Languages French.

Arabic, France’s second-most spoken language, was featured at this year’s Avignon Festival, but is Arabic is still the outsider's tongue?

The evening before traveling to Avignon for the theatre festival, I was invited to a dinner in a chic part of Paris. The conversation languished around anti-ageing treatments, the dangers of parmesan cheese (“it’s incredible that people still eat dairy”) and everyone’s plans for the summer. I mentioned my upcoming trip to Avignon, which was greeted with gasps of joy for the beauty of the city and its acclaimed festival, founded by Jean Vilar in 1947. When I enthusiastically added that the “invited language” this year was Arabic, the gasps turned to horror. One guest, in a position of influence, proclaimed “I cannot stand to hear this ugly language on the streets of Paris!” to general murmurs of agreement. Disgusted, I defended the language and the festival’s choice, but it was difficult to shake off the violence of this encounter. A few days later, someone from the festival told me of the tsunami of criticism they had received on social media since announcing this year’s program.

Arriving in Avignon, the first stop is the hub of the festival, in the courtyard of the Cloître Saint-Louis. Here, many of the live interviews, debates, conferences, and professional meetings take place. One of the first to speak was the Franco-Lebanese journalist Nabil Wakim, whose influential documentary La Mauvaise Langue (a play on words, meaning both gossip and implying that Arabic is “the bad language”) was screened as part of the “Territoires cinématographiques” selection. The film looks at the place of Arabic in France, the prejudices around it, and why, though it is the country’s second most-spoken language, it is barely taught in the national curriculum. A self-proclaimed “illiterate” in his mother tongue, Wakim’s talk, “Comment j’ai perdu ma langue” (How I lost my language) looked at the reasons behind this and the impact it has had on his life and the others whom he interviews. I had seen the film in Paris six months earlier, having been drawn to the topic after another unsettling encounter, this time with the Algerian born French artist, Mohamed Bourouissa. At a talk about his exhibition at Palais Tokyo in Paris in the Spring of 2024, he described his move to France from Algeria as a child, and the prejudices he had experienced growing up. Curious about his relationship to Algeria today, and knowing he uses language in his video art, I asked him if he worked in Arabic as well as French. He did not like where I was going with that. “I find your question naive. You should understand,” he said, “we live in France and must speak French!” He added that he did not speak fluent Arabic. Later in the bar, he came to apologize for the way he addressed me and we had a nice exchange in French and Arabic.

Yet it was not until I saw Wakim’s film that I began to understand his position. First, there is the prejudice around the language — too often seen as the language of “Islam, of terrorism.” Second, the lack of opportunities to learn Arabic in schools in France — there are only 150 teachers of Arabic employed in the whole state education system — and attempts to change this, such as former Minister of Education Najat Vallaud-Belkacem’s project to improve the teaching of the language, have been blocked by right-wing politicians, claiming it would breed extremism. I have heard, first hand, parents at a top Paris public school saying, “We would withdraw our child if Arabic was taught at their school.” The result is that Arabic is the least transmitted mother tongue in the country.

Following the success of the film, and his book L’Arabe Pour Tous, Pourquoi ma langue est taboo en France (Arabic for everyone, Why my language is taboo in France), Wakim has become a symbol, if not ambassador, for this “not speaking” of Arabic, appearing everywhere from the Institut du Monde Arabe to INALCO (Institute national des langues et civilisations orientales). The Avignon festival asked him to curate a series of talks around this question. Despite the fact I was starting to wonder why he didn’t just learn Arabic, I was glad that he had been invited and the subject was out in the open. The issues he raised were echoed by Jack Lang, director of the Institute du Monde Arabe, in his booklet written for the festival, La Langue Arabe, Une Chance Pour La France (“The Arabic Language, An Opportunity for France”). In this time of fanaticism and popularism, we need to dare. Tiago Rodrigues [director of the festival] has dared to break with clichés, prejudice and above all, ignorance. He has dared to confront the fear-mongers.” Without Rodrigues, he stresses, the Arabic language would not have been celebrated in Avignon.

Having thus established the context in which the festival was presenting its program, namely the prejudice towards Arabic in France, I assumed the selection would move the debate on to challenge this ignorance. I was excited to discover a program with performances in Arabic — both international and local — and curious to see how they would be received. However, the “absence of Arabic” was echoed in the program with a selection that mainly included dance, translation, and discussions about the language rather than in it.

In an interview with Les Inrocktibles, France Culture’s publication about the festival, in reference to the Arabic program, festival director Rodrigues is quoted: “We found that the relationship to language in the context of a spoken dance, was more poetic than in the medium of theatre. This relationship to language that puts the body in play…” It is not clear if this idea was in his mind when he went looking for the Arabic language in work from the region and in Europe, or whether this theme evolved in response to the work he encountered. It is true that to see contemporary dance from a region that is often wrongly associated with hiding the body, the female body in particular, was an important programming decision. I overheard many audience members commentating that they were happy to discover this contemporary dance from Tunisia, Morocco and Lebanon. But I did not understand why dance should be the dominant, almost exclusive programming choice.

The title of the first show, They always come back [sic] by Franco/Moroccan choreographer Bouchra Ouizgen, raised the questions “Who will always come back? And to where, and to what?” As I watched the performers, I was conscious of my need to translate the dancers’ movements into words. “Perhaps that movement is a reference to welcoming someone home,”’ I asked myself; “is that music referencing a wedding?”, and in which language should I pose such questions? Is it possible to have a “dialogue” with this spoken dance if I myself do not reply in movement?

Nor was there any spoken language in the opening show that followed it: NÔT by this year’s “artiste complice,” Marlene Monteiro Freitas. A version of 1001 Nights that divided the audience: many booed and walked out in disgust, finding it had nothing to do with the tales and was needlessly provocative, while others cheered in ovation. I fell into the second camp, finding it an original take on the folly and madness of absolute power and on the genius of Scheherazade. Rodrigues’ notion of “spoken dance” communicated itself more fully to me in this performance, and my urge to translate the movements I saw on stage into words, was significantly less.

The next day after leaving the dance performance Laaroussa Quartet Un Corps Libre qui invente son proper geste (Laaroussa Quartet a Free Body that invents its unique gesture) by Tunisian choreographers Selma and Sofiane Ouissi — a performance about the transmission of movement through generations of women — I saw a group of twenty or so women picnicking under a tree in the park opposite. They were celebrating a child’s birthday, clapping and singing in Arabic. I approached them and they told me they lived in Avignon. I asked them if they’d had a chance to see the performance in the theatre across the street, but they hadn’t heard about it. That same evening, heading to another performance at the spectacular Carrière de Boulbon (a former quarry turned theatre), I overheard the taxi driver speaking in Arabic, and asked him how he felt about Arabic being the invited language this year. He said he didn’t know about it, but told me that the year before, his brother, also a cab driver, had been invited by a passenger to attend a show at the Carrière as he had an extra ticket. His brother had enjoyed it. I listened attentively, trying not to make any assumptions. But I did question why the festival, which included Arabic in its leaflets and handouts, had omitted it from the main posters they’d put up everywhere in town. I sincerely hoped it had nothing to do with the social media attacks they’d received.

Ali Chahrour’s When I Saw the Sea had a long line of people all hoping for someone’s extra ticket. The hybrid dance-theatre piece tells the story of three Ethiopian women, who perform as themselves, as they struggle to escape the kafala domestic worker employment system in Lebanon during the onset of war last Autumn. It was the first time I’d heard Arabic being spoken on stage thus far, and it was chilling to hear the women share their stories of semi-slavery. They did not have the luxury of choosing whether or not to learn this language; even their names had been changed for Arabic ones, and they spoke it well, albeit with strong accents. But as the performance showed them liberating and reclaiming their true selves, they switched to Amharic, their mother tongue, and Arabic was largely left behind. It was particularly strong programming: as well as being excellent, it gave space for “foreign” voices from within the Arab region: a reflection of the actual diversity that exists there, but which is all too rarely shown in Arab festivals or those in Europe (despite the emphasis they usually place on diversity and inclusion in their own territories). However, the performance could not really be categorized as theatre in Arabic, so I continued searching.

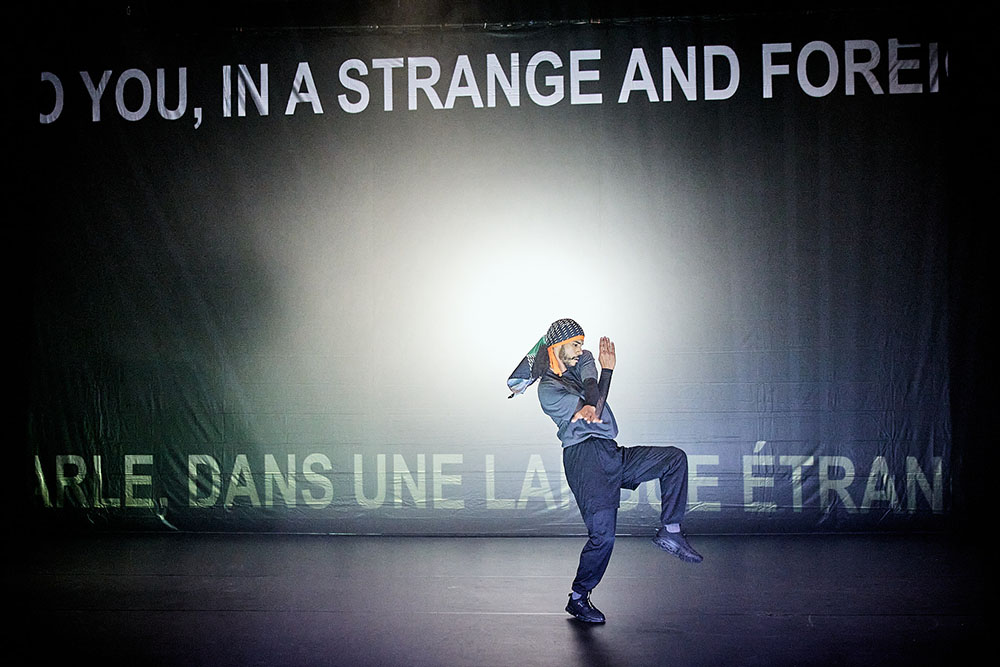

Tunisian choreographer Mohamed Toukabri’s choreography Every-Body-Knows-What-Tomorrow-Brings-And-We-All-Know-What-Happened-Yesterday, explored the crossroads between the three languages he uses in his daily life: English, French and Arabic. He did not speak, rather his theme was explored through words projected on the screen behind him as he danced. It began in English and French asking us which language should he use? Then Essia Jaîbi’s text appeared in Arabic without surtitles, rather accompanied by the words “I will not be translated” in French and English. This idea was developed with more English and French words, informing us he did not want to share everything about himself. It was an interesting performance, the dance a strong mix of hip-hop and contemporary dance cultures, exploring what it is to be an outsider in Europe. I can imagine it will have a strong impact in Belgium where he is based, when it tours to different cities this fall. Belgium has its own linguistic tensions between Flemish and French, but to my knowledge less of a conflict with Arabic. But here in Avignon, seeing the performance in the setting of France where Arabic is the second language, and in the context of Arabic being the invited language at the festival, it threw up many questions. Is refusing to translate Arabic the way to address the prejudices against it? Why did the festival program a work that assumed no one in the audience would understand the Arabic? If this was the case, then what is the function of choosing to celebrate a language, without ensuring that members of the community who can speak it, are also present? And finally, why was the notion of putting unfiltered, spoken Arabic on stage at the festival becoming so complex?

My first and only encounter with literary Arabic in a theatre performance was unexpected. The official program included many works that weren’t part of the Arabic language invitation. One of these was Joris Lacoste’s Nexus de l’adoration, a gorgeous, ironic and acutely relevant imagining of “all the things in the world.” From electronic cigarettes and laundry detergent to social media speak, the talented cast performed a sort of post-postmodernist, joyful collision of the disconnected. This idiosyncratic work imagines a new religion that in Lacoste’s words “wants to be as welcoming as possible… that celebrates all sides of life and non-life, that accepts all and rejects nothing.” Halfway through the performance, with no introduction, one of the actresses recited a poem by the late Palestinian poet Hiba Abu Nada, followed by her own translation into French, with the last line being “nous sommes tous Gaza” (we are all Gaza). The inclusion of the poem went beyond a moment of solidarity for Gaza; I found in it a statement of solidarity and acceptance that Arabic is part of the fabric of France and of everyday life, and does not need introduction, translation or explanation. I congratulate Lacoste for placing it as he did.

During his closing speech, Tiago Rodrigues acknowledged the criticism in the French press that there had been insufficient Arabic on stage. He rightly reminded us of the two evenings organized by the Institute du Monde Arabe, the first celebrating Oum Qulthoum, the second, Nour, dedicated to Arabic music and poetry in the original. He also reminded us of a number of films in Arabic and the theatre-dance performance Yes Daddy from Khashabi Theatre, Haifa, performed in Arabic, written and directed by Bashar Murkus, with dramaturgy and production by Khulood Basel, to come during the last three days of the festival (I had sadly already left and was unable to see it). There was also the semi-staged, performance reading by Wael Kadour entitled Chapître quatre which was totally sold out — proof if it was needed that people really did want to hear Arabic theatre. Rodrigues shared that two other performances had cancelled due to the political situation in the Arab region, and he hoped they would come next year. He did not say what they were or if they are text based. He was proud that this was the first time in the festival’s history that the country of Palestine was attached to an artist’s name, and he reminded his listeners of the organized and ongoing attacks against his programming choices from the Far Right.

I agree with the much-voiced criticism in the press and among the audience, that having made this bold choice to have Arabic as the invited language, there should have been much more unfiltered Arabic on stage: without music or dance to soften it, without being explained or categorized, translated with surtitles certainly, but spoken in the original. It would be tempting to conclude that the lack of Arabic language on stage was due to the attacks the festival had received, or to a failure to break from the culture of silencing the Arabic voice in France. But this is too simplistic. The criticism they were receiving was not only about the language, it was also about the presence of artists from the Arab region. If they had been put off, then why include any Arab artists? The answer as is so often the case, may be more complex. First, there is the question of how programmers select performing arts from the Arab world and what access they really have. How work is too often bound to the editorial position of European overseas cultural organizations such as the French Institute, British Council or Goethe Institute, in the absence of or because of conditions attached to State arts sponsorship in the region. These questions are beyond the scope of this article, but they certain merit further examination. Then there is the fact that at this 79th Édition of the Avignon Festival, dance, along with doc-performance, dominated all the programming, not just the Arabic language.

I’m still asking myself: is the playwright old-fashioned or just out-of-fashion? I believe part of the “not-speaking” Arabic was also part of the “not-writing” theatre.

The playwright was conspicuously absent. Yes, there was Rodrigues’ new play La Distance, which he himself directed. In his introduction, he strongly defended theatre as “part of the human adventure,” and there were performances of Ibsen’s Wild Duck and Aeschylus’s The Persians in which latter Gwenaël Morin’s uncompromising staging became a humbling and challenging experience in listening, after so much watching. However, there was very little new writing featured. Days later, I’m still asking myself: is the playwright old-fashioned or just out of fashion? I believe part of the “not-speaking” Arabic was also part of the “not-writing” theatre. There was much talk of the “language of the body” with dance implicitly replacing, rather than co-existing with the spoken word. Docu-performance was strongly present, with Aurelie Charon, director of Radio Live, even reassuring the audience none of what they were about to see had been “written”; it was just their conversations. Affaires Familiales staged transcripts of interviews with lawyers; Le Procès Pelicot re-enacted parts of the trial using journalists’ notes to pay homage to this remarkable woman. There was a silent drama-dance, Mami, from the talented young Albanian director Mario Banushi, and deconstructed language in Swiss director Christoph Marthaler’s Le Sommet (“I recognize a part of humanity that should be able to communicate but which is no longer able to”). Taken individually, the majority of these shows were compelling and important. Taken collectively, they appeared to condemn the playwright.

And so my biggest reflection after two weeks of the festival is: having identified a breakdown in our language communication, as artists such as Martheler, Lacoste and Toukbraki have done, should theatre merely mirror it back to us, or resist this bleak diagnosis? Should we be content with putting our own mothers and fathers on stage — as in Israel and Mohammed and Radio Live — rather than crafting the story of a Mother Courage for our dark times? Is this the end of theatre’s capacity for transmission — through texts that can be studied at schools and re-performed? and through texts that can be translated and transmitted throughout the world? If you are not physically present at the moment of the original performances, will you miss out entirely?

Some young theatremakers at the Off Festival had a different perspective and made the text the thing. If you are part of the fashion of “non-playwriting,” you could argue this is due to inexperience, but it may also be because they are free from the weight of all the explaining, contextualizing, categorizing and translating that seems to accompany those in the French spotlight. Yes, their work was less sophisticated visually and conceptually, but it achieved a power that I had missed in the main festival. In a bilingual Arabic/French production of Racine’s Bérénice, the director Marie Benati (Nuit Orange Theatre Company) gave form to the idea that the two languages are equal and need no justification for their presence side by side. Then there was the first show from Saudi Arabia at Avignon, The Hoop, presented by the Saudi Theater and Performing Arts Commission, written and directed by Fahad Aldossary, performed in literary Arabic with surtitles. It was my sole experience at the festival of an Arabic speaking audience, and contradicting those who claim literary Arabic has no place on the contemporary stage, it was greeted with spontaneous clapping and enthusiastic cheers of approval throughout. The play tells the story of five employees stuck in autopilot on their pathway to freedom. With wit and humility, the characters called for change and a new start. They are clearly referring to their own country in the midst of monumental change, but their words might well apply to us all.

On the train back to Paris, hearing the TGV announcements in French, English and Italian, I found myself missing the pre-show reminder to switch off our phones in French, English and Arabic. Later on in the metro, there was an announcement in French, Spanish and Japanese. I wondered if the real litmus of change in this country will be when the transport announcements are finally made in France’s second language. Perhaps only then will Arabic finally become a “Chance pour La France” (an opportunity for France) as Jack Lang writes, and as Tiago Rodrigues surely intended when he chose it for the invited language. A “chance” for many things, not least to celebrate the beauty of this language, and bring people together rather than force them apart. To put an end to those who try to prevent it from being spoken in public because they do not wish to hear it, from fear of what it will provoke. And to allow the language to be transmitted naturally through education and the family. It could well be the moment for a playwright to take up this challenge.

More information about each Avignon show and its upcoming touring schedule can be found on the official website.