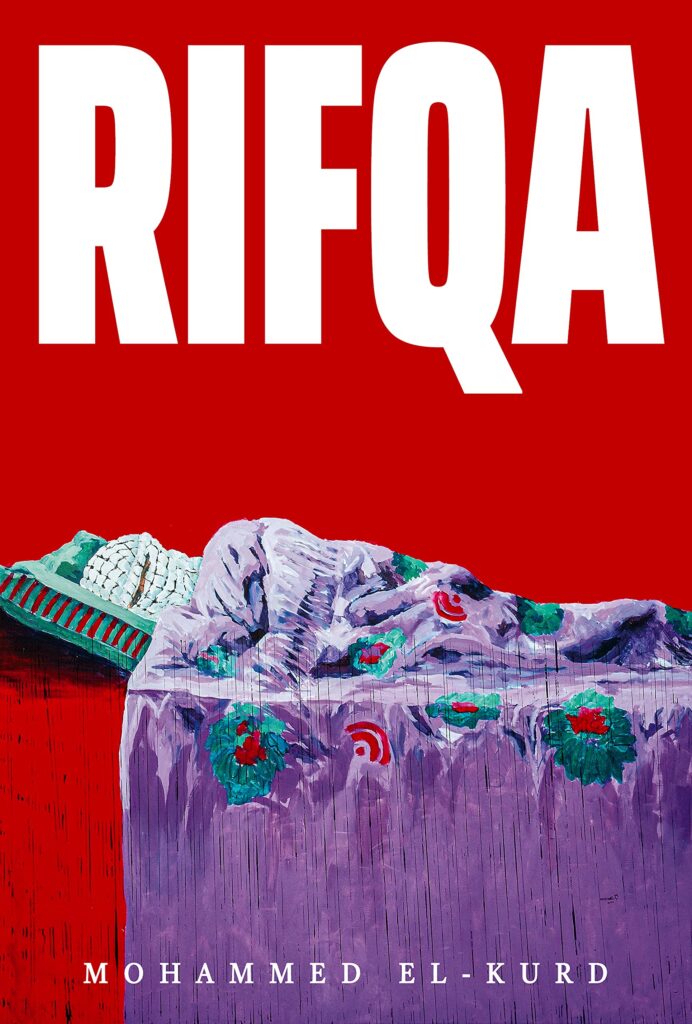

Rifqa, poems by Mohammed el-Kurd

Haymarket Books (Sept. 2021)

ISBN: 9781642595864

India Hixon Radfar

Poet Mohammed El-Kurd often plays by pairing his words, thus doubling or halving their meanings. He is himself a twin. You could easily miss it. Three short lines hold the story: “I /and my sister/ were born,” two infants born into the dichotomy of Israel and Palestine on the 50th remembrance day of the Nakba. “You are the orphan,” “You are the womb.” Mohammed and his sister shared their nutrients in the womb but entered a world where one group is trying to take all the nutrients from the other without really thinking how that will end. The Nakba, or Catastrophe, is celebrated the day after Israel commemorates its Independence Day.

There is conflict outside the hospital on the day Mohammed and his sister are born; the words of protest and liberation chants are retaliated against in significant ways. People die right outside the hospital on the day Mohammed and his sister are born. “Birth lasts longer than death./ In Palestine death is sudden,/instant,/constant,/ happens in between breaths.”

I had already formed a hypothesis about Mohammed’s doubling from the very first moment I saw the book’s title. Rifqa is the Arabic spelling of a name I have also seen transliterated from the Hebrew as Rifka, or Rivka. I did not yet know that Rifqa is also the name of Mohammed’s grandmother.

It turns out that the Arabic version is a common name for girls. It means kindness, gentleness, company, companionship. As I get to know Mohammed’s grandmother through his poems, I appreciate the choice of name. But this Rifqa also has a tough side: she is an activist fighting tirelessly for her cause, becoming harsh when she must in order to achieve a more lasting and universal kindness.

Arabic words often have their twin in Hebrew, and the Hebrew definition of Rivka takes the mind some time to get around. Rivka is no longer a common girl’s name in Hebrew by the way; in fact, it hasn’t been used much in the past 100 years. The name Rebecca is a form of Rivka, which has the specific meaning of “to bind.” Rifqa el-Kurd was alive 100 years ago and surely knew girls around her age who were named Rifka or Rivka. But as her grandson was growing up, he probably did not.

Rifqa El-Kurd and her family had to leave their house in Haifa in 1948 on the day of the Nakba. And they had to keep moving after that until they finally landed in what they hoped would be their permanent home in East Jerusalem. Rifqa experienced multiple catastrophes in her life but also much success as an activist until her death at the amazing age of 103. Her grandson doesn’t tell us the day and year she died. In ways, he can’t believe she is gone, and he still can’t write her eulogy. This book is not her eulogy. Instead, as he tells us in his afterward, she just always ends up in a lot of his poems. She was the ultimate fighter. “Even in the face of eviction, monetary punishment, tens of trials, and threats of imprisonment, she persisted. ‘I will only agree to leave Sheikh Jarrah to go back to my Haifa house that I was forced to flee in 1948,’ she famously said, demanding her right of return.”

In the poem “Portrait of My Nose,” El-Kurd writes “My grandmother’s is beautiful, mine is/ one nose away from beauty.” The book is Mohammed’s tribute to Rifqa. There is deep love between grandmother and grandson. He is on her path. She is in his poems even while he is studying in America. Sometimes he wants to hide his thoughts from her when he is not proud of them. In America, Mohammed’s family is acutely absent to him. So is the anger and drive Rifqa taught him to channel into activism ever since he was a child.

Even in the face of eviction, monetary punishment, tens of trials, and threats of imprisonment, she persisted. ‘I will only agree to leave Sheikh Jarrah to go back to my Haifa house that I was forced to flee in 1948,’ she famously said, demanding her right of return.

Mohammed shows us how he becomes despondent when he is away from the fight. “Despair without people tastes different than collective despair.” He does not make it home to Palestine in time to see his grandmother before she dies. Rifqa is gone, yet another rift in Mohammed’s life.

100 years ago, when Mohammed’s grandmother was at the beginning of her life, the Hebrew name Rifka would have made more sense to use for an Israeli girl with a Jewish background. The Levant was bound together then, it was cohering, people coexisted. Maybe we have almost forgotten this other meaning of the word ‘to bind’: that we can also bind kindly, companionably. Now the people of the Levant have mostly lost their bond. At the very least, there is a gigantic rift, and the meaning of a name flips to its twin, becoming ‘to hold and restrict by force.’ Who would name their daughter after a political and moral bind? Who would name her with a word that also means ‘to wrap around with something’, ‘to enclose or cover’ as a captor might?

Mohammed tells us that he was 12 when he started writing his first “typo-ridden” poems, as he calls them. His mother is a poet who was getting published as well as censured in Israel’s literary journals at the time. But there is another important event that happened in Mohammed’s life when he was 12. This is the one that I think pushed him towards the halving and doubling of his words. I am speaking of the 2009 confiscation of half of the El-Kurd home in Sheikh Jarrah, East Jerusalem by some settlers. Mohammed’s grandmother tried everything she could in the courts to get the settlers out, to get their house back, but they still lost half of it and ended up having to live with the settlers, actually sharing half of their home, the lives of the two families “separated only by drywall.” The El-Kurd family became internationally known for this and Rifqa used the fame of her home as an international platform for her work as an activist. Mohammed’s life had been changed irrevocably from that moment on.

Often what is most disorienting in life is most beautifuI in poetry. Sometimes El-Kurd’s twinning doubles, as in “tomatoes and cucumber,” the perfect combination, but sometimes it halves: “Tear gas and tea” — words that are uncomfortable to hear together, words that tear at each other. I personally find as an American reader that the poems in Part One emote a surprising beauty. Later, Mohammed wants to disown these poems, but I am extremely glad he includes them here. They are not his typo-ridden poems of twelve, but sixteen or seventeen, and he is already approaching masterful in them. Too timid, he critiques them later: “English calls sentimentality tacky.”

There are four parts to the book that proceed chronologically. Somewhere along that chronology, probably in college in Atlanta and definitely in graduate school for poetry in Brooklyn, he feels he knows more about poetry than he did when he was seventeen. But what do we ever really know about writing a poem? At what age do we learn it? Where? Who teaches us? Starting his book with his early poems is a brave and good place to begin.

It is true that later his poems become more complex. He takes on new forms, tries new things. “I’m bored with the metaphors,” he states in the first poem of Part Two, weary of the words he used in Part One. Of course he is. Of course his poetry will have to change in America.

By Part Three he has stopped writing exclusively about home. By Part Four he finds himself apologizing for the liberties he is taking with his syntax to those back home: “My apologies for my inverted syntax/ I am reluctant to say what I write about.” He is starting to hide in his poems, as so many American poets do. Is this what an American education has taught him?

After quoting Nicki Minaj at the beginning of a poem about his time in Atlanta, he writes, “Female rap is the highest form of poetry.” In New York he says, “I have never once felt free anywhere,” “Bike through Brooklyn:/ Jewish neighborhoods/ Radio Israel.”

He sees his grandmother again for the last time before she dies, but her mind is already more poetic than lucid. She may not be sure who he is, but when he tells her that he is studying in America, she says “Why America? Be careful! Tell them,/ America is the reason.”

By the end of Part Four, in a poem called “Bush,” El-Kurd writes “Shoe to the head./ I’ve never felt pride/like this.” In a poem entitled “Why Do You Speak of the Nakba At the Party?(after Rashid Hussein)”, the last line simply reads “Oh,/I forgot to tell you, I spoke of the massacre at the party.” His humor is back. “If we don’t laugh, we cry,” Rifqa often said. Later on in that same poem called “Bush,” he says of an Iraq war veteran he meets, “They think they’re the only ones/ with PTSD.” Then, of himself and his people, he decimates us by writing “we live like walking debris.”

At 24, Mohammed El-Kurd is already a poet of note. He is also a visual artist, and an activist like Rifqa. He has synthesized and overcome his American education in poetry. He no longer feels like he has to hide in his words.