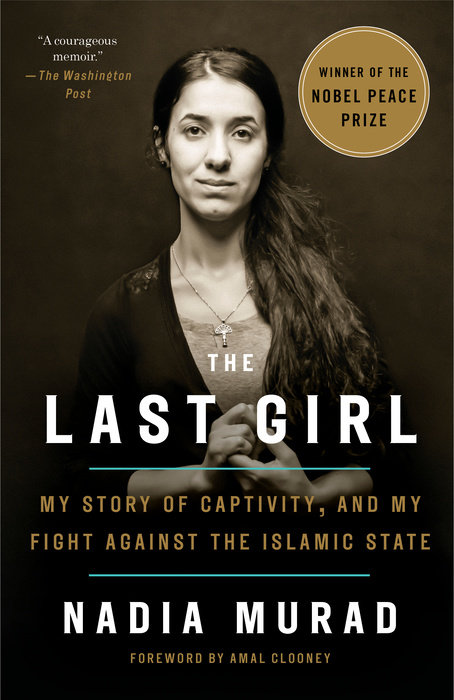

The Last Girl, My Story of Captivity, and My Fight Against the Islamic State

A memoir by Nadia Murad

Penguin Random House

ISBN 9781524760441

Maryam Zar

Nadia Murad’s tale of captivity and humiliation at the hands of ISIS, and her eventual escape and rescue are a harrowing account, bravely relived for the benefit of the world.

Although few readers will be unfamiliar with the narrative of Daesh or ISIS in the conflict lands of Iraq and Syria — or the ordeal of Nadia and thousands of women like her — the details of fear and humiliation borne by the psyche of girls in order to demoralize and strip them of their identity is a difficult narrative we are all better to endure.

Nadia is the eleventh and last child of a Kurdish family. She was abducted from her hometown of Kocho when she was only 16 years old. Kocho is a Yazidi village in the Sinjar region of Iraq, made up of farmers and shepherds. She has childhood memories of long drives through the countryside, sandwiches along the way with a doting mother and a brave father of whom she is proud. She takes the time to recall better days at the side of brothers and cousins, poking fun and playing pranks, and recalls coexistence with neighbors and friends, like anyone would.

Still, Murad speaks of prejudices hardening into hatred as the war in Iraq dragged on after the US invasion; “relationships burdened by centuries of distrust” beginning to bubble to the fore. Eventually, even the kind coexistence that populates her childhood memories begins to break apart into the seeds of violence — a violence that creeps into her neighborhood with signs of brutality from the start.

The war that the US brought to Iraq in 2003, with the promise of a swift takeover of power and a welcoming populace, bled into a lasting conflict fueled by local rivalries and vicious territorial battles that decimated communities and laid a nation to waste. The Last Girl chronicles the slow slide into conflict and the incremental realization that the coexistence her community had long enjoyed with their Sunni Muslim neighbors was unraveling.

Yazidism, Murad explains, is an ancient monotheistic religion that is spread by folklore through holy men and families, and passed down the generations. It is not what we term as a “book religion” and for that reason, Yazidis have been the target persecution from the Ottomans to Saddam who looked down upon them as idolaters and devil worshipers — all because there was no book. Still, it was Yazidism that held her community together and gave them the sense of unity and pride that infused her childhood, and still sustains her determination today.

In truth, this is an all too familiar story for many refugees who watch in disbelief as their lives succumb to the destruction of war and conflict, waged by faraway strategists whose only calculus is a tactical one, not a human one.

As the Iraq war raged in what seemed like uncontrolled new directions, the Kurdish Peshmerga formed to defend the Kurds near Erbil. People in Sinjar asked to form their own deterrent force, but were rebuffed. Nadia Murad tells of weapons slowly coming into the home, and checkpoints being manned by brothers and cousins as villagers began to realize that the old, comfortable order had receded, and a new brutal reality was setting in.

The slow demise of life as they knew it reminds me of Malala Yousafzai’s description of the same slow unraveling of the village surrounding her when the Taliban set in. In truth, it is an all too familiar story for many refugees who watch in disbelief as their lives succumb to the destruction of war and conflict, waged by faraway strategists whose only calculus is a tactical one, not a human one.

A defiant spirit with a bold instinct, Murad writes that she never thought she’d live anywhere outside of her village of Kocho. As life would have it, she is now the friend and client of Amal Clooney and a global ambassador for women’s empowerment while being the face of resistance for women around the world who endure the degradation that their gender infuses into their lives. Nadia Murad’s harrowing journey from Kocho to the underbelly of ISIS, where she endured rape and abuse at the hands of Muslim men whom she may well have deemed dirty, all while learning to keep quiet and hide her indefatigable spirit for freedom —which ultimately led her to a daring escape — shows us that we dismiss the strength of women at our own peril.

It is hard to read her story, especially as a woman. There are layers and layers of injustice she chronicles, not just with war and brutality but with small acts of gender-based degradation to which one becomes accustomed, but never quite comfortable with. As she recounts tale after tale, and laments the loss of family members she knows are enduring the same degradation at the mercy of men with power and seemingly no conscience, she writes of her people, “we would, over generations, get used to a small pain or injustice until it became normal enough to ignore.”

She becomes the slave or “sabaya” of a high ranking ISIS commander, Hajji Salman, who proclaims her as his own. Living in his house, Nadia sees ISIS up close and understands the way they relish the pain they inflict upon the communities they overtake. She lives with Salman in a house in Mosul which had clearly been taken from its former wealthy inhabitants —an Iraqi family no doubt taking refuge in some adopted homeland away from the conflict. She watches as they hoist their black and white flags and spread their jihadi propaganda, all while occupying the nicest homes first and looting what’s left of the towns they roll into, turning schools into military bases and destroying artifacts they deem un-Islamic.

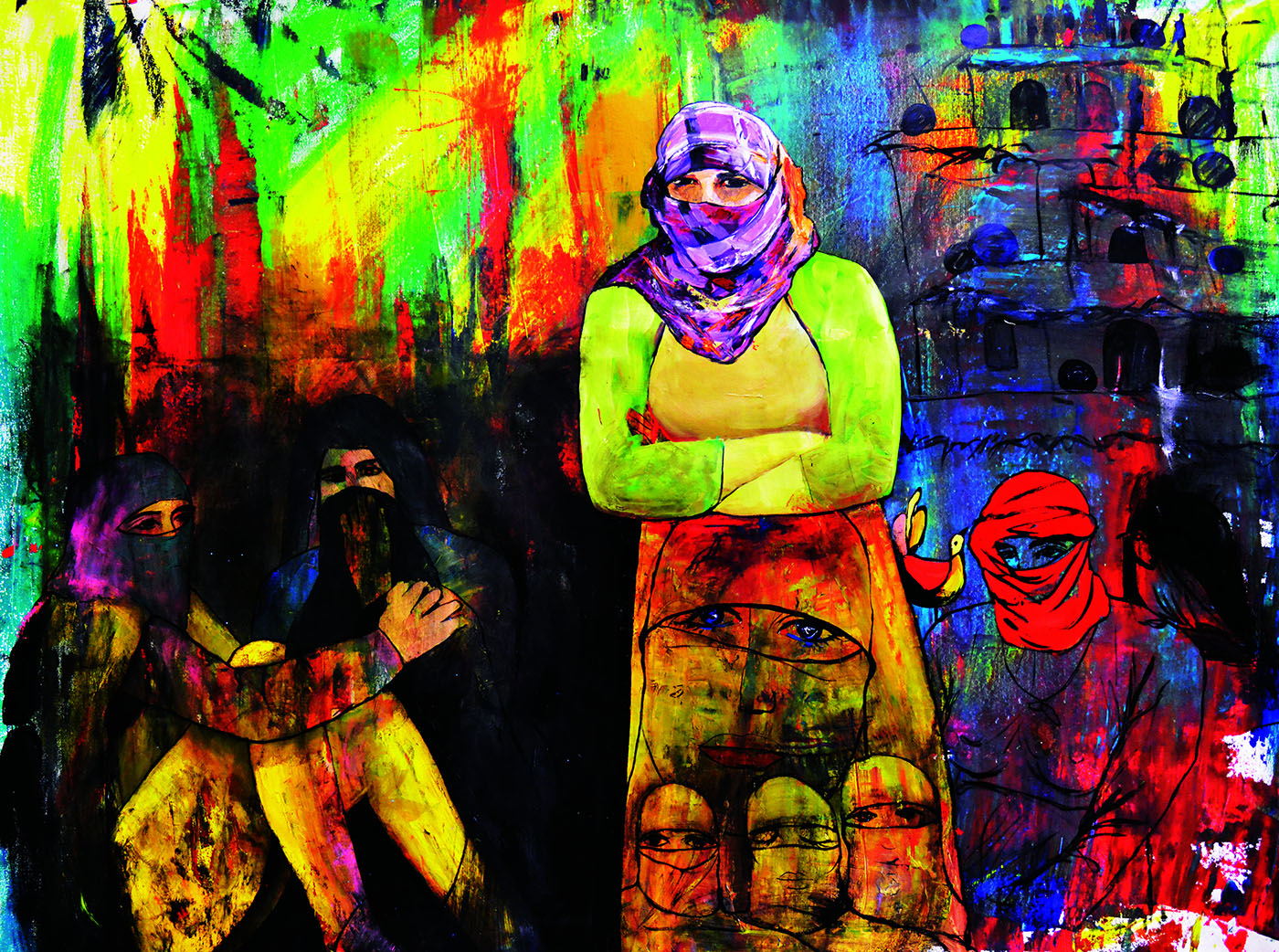

More than anything, this book is a chronicle of the resilience of women. She describes unflinchingly the brutality of the rapes and the humiliation of the slave markets where women are bought and sold randomly like commodities:

We would be bought at the market or given as a gift to a new recruit or a high-ranking commander, and then taken back to his home where we would be raped and humiliated, most of us beaten as well. Then we would be sold or given as a gift again, and again raped and beaten, then sold or given as gift to another militant, and raped and beaten by him, and sold or given and raped and beaten, and it went this way for as long as were desirable enough and not dead yet.

After revealing such horrors, Murad gives a harsh rebuke to the Arab women and the communities who watched as all this happen to Yazidi girls.

As if she knows that this world is desensitized to the violence visited upon women around the world, she reminds the reader that the rapes were the worst part. “It stripped us of our humanity and made thinking about the future…impossible.” Still, she claims that future, even though she endures a brutal whipping after her first attempt at an escape and fears being caught. She finally finds the determination when she realizes that all the abuse, the brutality, the whipping and the rape are designed to sap her of her spirit to be free, and she won’t let that happen.

Given a moment alone and an opportunity to flee, she musters the determination to risk it all again, as she swings her bag over a short wall and rushes toward freedom. “My heart beat so hard in my chest that I worried people I passed would hear it and know what was.”

This is a book well worth reading. It is not an easy read, clear through to the end where even in escape, Nadia Murad is forced to relive Iraq’s war-torn pain. Not so much for the disturbing details of physical and gender-based violence that we might expect, knowing what the Yazidi community has endured, but for its spirit of triumph and its tale of war the way it impacts ordinary people, this is a book we need now more than ever.

Writer’s note: These people who experience brutal conflict and flee their lands for better opportunity are no different from you and I, the writer and reader of this review. They are ordinary people caught in extraordinarily brutal circumstances, through no fault of their own. Remember that the next time you cheer or condemn a conflict far away from your own homeland.