Liberating Women’s Bodies for Whom? The Abdellatif Kechiche Controversy

and the Scope of Cinematic Voyeurism

There is no need to call on statistics to see that it is largely women who have to go naked in front of the camera, particularly for sex scenes.

Viola Shafik

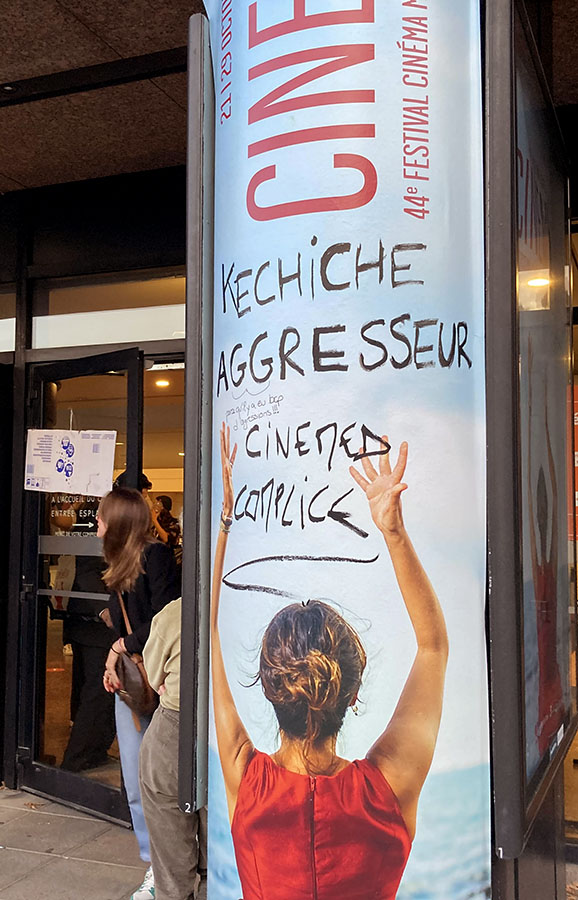

One nice late afternoon on my way to this year’s CINEMED film festival in Montpellier, I found myself in front of closed doors. Security personnel had locked the festival’s central site, the Corum. In front of the main entrance, a group of protesters had gathered, chanting, holding banners and distributing leaflets in the name of the Mouvement H/F Occitanie LR. With their intervention they wanted to draw moviegoers’ attention to a fact they considered unacceptable; namely, that the festival had invited the French-Tunisian director Abdellatif Kechiche (b. 1960) to run a masterclass at this year’s edition:

“We want to remind people that this director has been accused of sexual aggression.”

What they hinted at was the case of a 29-year-old woman who had gone to the press in 2018. She had filed (in vain) a lawsuit against the director for sexual abuse but was belittled as a “person who did not find any other means to get herself known than attaining the status of a victim,” according to the group’s leaflet. The activists also asserted that in France only two percent of sexual aggression allegations are made on a false basis, while 90% of the cases get closed without further action. Blaming a cultural event such as the CINEMED for siding with the alleged perpetrator at the expense of women made sense, of course, particularly because the director had had other complaints lodged against him. Another Mouvement leaflet explained:

”Those who work in cinema, on film shoots, are familiar with Mr. AK’s reputation. They know, as testified by the actresses with whom he worked but also the assistants and the technicians, and the service providers, that this director employs methods that endanger the physical and moral integrity of the people who work with him and for which he bears the responsibility as head of the project.”

These lines, written by the Mouvement H/F Occitanie LR, points to a much larger problem to which female performers are exposed due to contemporary media practices, that is, gazing, voyeurism and, occasionally, sexual harassment. The nature of these practices, I would claim, are largely informed by unequal power relations on set as well as behind the scenes; they are tied to several factors: economic, social and, last but not least, visual representation in general.

There is no need to call on statistics to see that it is largely women who have to go naked in front of the camera, particularly for sex scenes. In 2018, US actresses launched the anti-harassment group “Time’s Up,” which emphasizes the precarious state of affairs in the industry that puts women in that context, at risk to be exploited sexually for the sake of their careers.

The Egyptian film scene, as well, had witnessed complaints voiced by aspiring actresses on the occasion of the premiere of Islam El Azzazi’s feature film About Her in 2020. It goes almost without saying that the media has been constantly pushing the borders towards sexploitaiton for the sake of profits and all the side effects women shoulder as the weaker players in a global economy, an economy still dominated by patriarchal heteronormativity.

For that reason the Montpellier incident made me want to slide further into the debate. The festival’s decision to showcase the cinematic oeuvre of Kechiche for art and film historical reasons is understandable. Nevertheless, I wondered how they could neglect the controversy and the entailed legitimate question to which extent the industry’s exploitative manners can be tolerated and how strongly they even get promoted when disregarded by the festival circuit, as in the case of CINEMED and more importantly the Cannes Film Festival in previous years, which incessantly rewarded Kechiche’s controversial work.

Naturally, thinking at first of the director’s impressive artistic achievements, the professional recognition he received for his original and innovative film language, plus his success in France despite his immigrant background, I felt hesitant to point fingers. Born in Tunisia, he was brought to France at the age of six. His career in cinema started successfully first as an actor in France, then in his country of origin. There he featured most prominently in Bezness (1993) by Nouri Bouzid who like others defined Tunisia’s new wave of critical auteur filmmaking. Politically, these directors pushed the boundaries of censorship to the extreme, also in terms of sexual representation, just remembering the notable hammam scene in Férid Boughedir’s Halfaouine (1990), which showed for the first time in the Arab world an immense number of topless women — a great success for freedom, we thought at the time.

Kechiche, in 2000, eventually joined the rank of film directors with his first film It’s All Voltaire’s Fault, an illegal migrant’s story, and had another great breakthrough with Couscous (better known as The Secret of the Grain, or La Graine et le Mulet in French) in 2007. Finally, for Blue is the Warmest Color (2013) he was awarded the Palme d’Or in Cannes. The most remarkable feature of his work has become his distinguished direction of actors that enables him to extract even from amateurs an amazing degree of realism, an overwhelming physical presence and expressive depth, a fact that made critics attach the label of “naturalism“ to his directing style.

The question remains, however, why did Kechiche in parallel to his distinguished career amass such a growing list of accusations? It started with the two lead actresses of Blue is the Warmest Color, despite the fact that the film was so lauded. They had objected publicly and vehemently to Kechiche’s directorial style, which included pushing them to the limits in a very intense and long lesbian love-making scene. Coming back another time to Cannes with Mektoub My Love Intermezzo (2017), a new controversy arose. The 27-year-old Ophélie Bau had her agent stand up against Kechiche to remove some shots from one central scene in the film before its launching. It caused her such embarrassment that it made her slip through the back door during the premiere.

At the press conference in Cannes and again in the absence of his lead actress, the director claimed to have tried, “cinematic experience as free as possible, breaking the narrative codes.” Sure, but what about the accusation “Of Plying Actors With Alcohol Until They Performed Unsimulated Sex,” which included the above mentioned infamous scene? It represented a 13-minute-long graphic cunnilingus between Bau and Roméo de Lacour as part of the film’s 3h28 hours long chain of partying. Praised by some as “the most radical portrait of a free woman,” others saw it just as “a crass, four-hour movie about twerking butts.”

To the film’s disadvantage, critics counted 178 (according to a last count) shots on the buttocks of young women in all kinds of positions, often stretched towards the lens, enlarged through the use of wide angle, sometimes filmed from below or at the same level instead of the eye-level that is commonly favored in cinema. Even during conversations, such as on the beach, the camera would spy along the uncovered thighs and hips of Bau to catch a bit of her face at the far end of the frame. In short, the mise-en-scene uses any possible occasion for female bums to fill the screen.

I am aware that my words can be easily misread as a polarizing moral debate, libertinage versus puritanism, or at best, machismo versus feminism. “It’s almost absurd to talk about the role of the male gaze in a film for which the male gaze is more integral than, say, the screenplay or the camera equipment. It’s the foundation on which the entire enterprise rests, and it doesn’t even supply the nuance for a worthwhile discussion,” wrote a (frustrated?) reviewer of Mektoub. But is that really a reason not to reason about the male gaze? Or shall I better say voyeurism in cinema?

Of course, I do not equate the male gaze plainly with voyeurism, which is an oscillating notion in any case, as it previously signified clandestine peeping on others (regardless of gender) in correlation to sexual arousal only. Now, in the era of audio-visual media and observation technologies, it has become a more general notion and is not necessarily tied to sexuality, at least not in a direct sense. Also the situation of gazing itself has changed. Except for candid camera programs, the ones filmed usually know they are being observed. Only the spectator still shares one common denominator with the classical peeping Tom. He or she are truly passive observers; in a movie theatre they come together as a sort of collective voyeurs who receive pleasure without exchanging it with others. This last characteristic certainly applies to male gazing as well.

In 1989, feminist critic Laura Mulvey aptly analyzed the strategies of the “male gaze” in film language, pointing out that it relied basically on isolating body parts through framing and editing as an ultimate objectification of the female body. “One part of the fragmented body destroys the Renaissance space, the illusion of depth demanded by the narrative; it gives flatness, the quality of a cut-out or icon.”

This might be indeed the real reason why the critics got frustrated with Mektoub. As with splatter or action films, the fragmentation of the narration and the excessive almost ritualistic repetition of isolated elements (here the butts) have become an end in themselves. The film is no longer about the story nor about female freedom, it is about the object itself, the fetishized body cut-out.

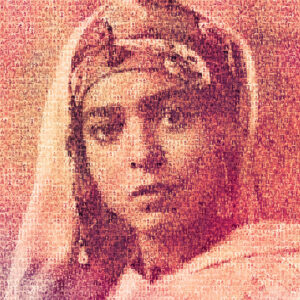

Years ago, like the above mentioned critic of Mektoub, I had a similar moment of puzzlement and frustration when watching one of Kechiche’s previous films, Black Venus (2009). I would have very much liked to have considered it a revelatory moment of post-colonial filmmaking, had it not been spoiled by the filmmaker’s ambivalent style. Starring the Cuban-born actress Yahima Torres as the tragic Hottentot Venus, the film told the true story of the 20-year-old South African Saartjie Baartman, who had been captured and brought to Europe in 1810, where her master exposed her caged body to the audiences of London’s freak shows. People flocked to see her because of her enormous buttocks and her visibly enlarged labia (both in reality the result of a disease).

The Hottentot Venus remained on display for five years during which she changed proprietors and was additionally forced into prostitution. After her premature death in 1815 in Paris, parts of her body including her private ones were conserved and exhibited at the Musée de l’Homme for 150 years, until Nelson Mandela claimed her remains back to be finally buried in her homeland.

Cultural critic and sociologist Stuart Hall, in one of his analyses of racism, when explaining his theory of Othering, cited Saartjie Baartman and her “fragmented” body as a prominent example of fetishization. Fetishization figures as one of the basic means by which the spectacle of othering, or, the cultural construction of the Other operates. Fetishization happens when the body of the Other turns simultaneously into an object of admiration and disavowal; we submit to a fantasy in denying ourselves access to it. Non-reciprocal gazing seems integral to this, as another case that Hall evoked in his analysis, may tell. For this he presented Nazi filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl’s photo series on Nubians during her African expedition in the early 1960s. In the pictures, the spectacular beauty of the predominantly young male naked bodies is juxtaposed with their people’s “primitive” way of existence, seemingly untouched by modern civilization.

Kechiche’s Black Venus, as the filmic plot unfolded, did of course underline the black African woman’s ordeal and the horrible effects that European racism had on her fate. But did the visual representation of Torres alias Saartje’s add to dismantling of fetishization, or release her body in any way from the inherent aggression of the gaze? I have to say, no, it didn’t. In realistically recreating for his actress Torres the same situations of violent and abusive voyeurism in front of the camera, perpetuated and excessively prolongued in many scenes, Kechiche turned the film into an ambiguously torturous experience for us.

As one critic who saw the director’s “punishing shocker of a film” at the Venice Film Festival contended: “One of the most repulsive scenes takes place before an audience of libertines, who push Saartjie to exhibit her private parts for their amusement and arousal.”

By implicating today’s audience in the same way, this “deliberately put the viewer in the extremely uncomfortable position of turning Saartjie into an object of sexual voyeurism once more.” And not only her, but also Torres who had willingly put on 15 kilos of weight to fit the role and had to offer all of her body endlessly to the camera.

Today, in thinking of these painful scenes, I find it even harder to distinguish between Kechiche’s critique of voyeurism and his — I should say affirmative — use of the very same technique. There is indeed only a thin line between criticizing abuse and inflicting on a woman performer — who admittedly gave her consent to be filmed — the same violence. The end does not always justify the means…