Defying a pervasive climate of self-censorship in Turkey, Kurdish artist Ateş Alpar grapples with cultural assimilation, historical erasure and methods of state control.

In Kurdish-majority southeast Turkey, the rugged terrain itself becomes a tool of government control, with patriotic slogans etched into stony mountainsides and the construction of massive dams forcing the relocation of rural populations to urban areas. It’s a physical and political landscape that artist Ateş Alpar knows intimately.

Alpar was born in 1988 in Nusaybin, a district of Mardin province just on the Turkish side of the border with Syria, but the family fled to the city of Adana in the 1990s — a period of bloody conflict between the Turkish military and the armed insurgency group the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) that ravaged the countryside, destroyed villages, and killed tens of thousands of people. This history grounds the artist’s new solo exhibition, Possibility and Probability, which draws from personal and family experience to examine methods of cultural assimilation and erasure, while also suggesting avenues of resistance.

Visitors to the exhibition at Depo, an independent cultural center in Istanbul, are greeted by “Barricade” (2025), a steel installation resembling the crowd-control barriers that have over the past decade become an increasingly permanent fixture on city streets around Turkey, as repressive security measures have spread far beyond the southeast. (Police fence off large swaths of Istanbul’s central Beyoğlu district, where Depo is located, at any hint of action by labor, LGBTQI+, or women’s rights groups.) Placed in front of “Protest” (2025), a tiny vintage TV set showing fuzzy scenes of unrest, the pairing evokes memories of police barriers being repurposed by demonstrators during the anti-government Gezi Park protests in 2013, reminding the viewer that the barricade is neither inevitable or inviolable.

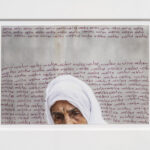

Video and photographic portraits from Alpar’s 2021 series What We Carry allude to a less visible form of state control, the restrictions on public use of the Kurdish language that have silenced people like the artist’s grandmother, who never learned to speak Turkish. One video image of her sits on top of a mound of soil, emphasizing deep connections to the land that transcend official narratives about who belongs to a nation.

The shape of this pile of dirt echoes the form of a barren slope in the image hung next to it, Alpar’s 2025 photograph “How Happy,” which shows these words in Turkish — part of the full phrase “How happy is the one who says, I am a Turk” — written onto the land. This is a common sight especially in heavily Kurdish parts of the country, where the slogan (coined by Turkish Republic founder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in the 1930s) is seen by many Kurds as both an erasure of their identity and a warning to stay in line. By only picturing the first two words, however, Alpar references this context while also seeming to imagine a possibility for a different, more open-ended conclusion to the sentence.

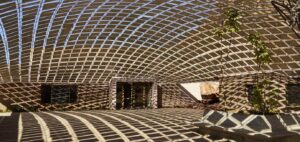

The arid landscape in “How Happy” recalls Alpar’s previous solo show Stone Shell Silent — the artist’s first — at Istanbul’s nearby Merdiven Art Space in 2023, which documented the ecological and cultural devastation brought about by construction of the Ilısu Dam. This US$1.4 billion project submerged the 12,000-year-old town of Hasankeyf and displaced tens of thousands of people, many of them of Kurdish or Arabic descent, from villages across the Tigris Valley. The artist’s photographs capture Hasankeyf in the midst of its slow death, with paved roads leading into rising waters, bodies being disinterred from the local cemetery to be reburied in higher ground, and people trying to go about their lives amidst a radically changed landscape. The body of work, created over a period of five years, is eulogistic but not passively so; it demands that the viewer also bear witness, that what has happened not be forgotten.

In May 2022, Alpar, who is also known as a performance artist, carried a photographic print of the battered multilingual road sign (in Turkish, Kurdish, and English) that had once welcomed people to Hasankeyf through the twisting alleyways and sunbaked squares of nearby Mardin during the opening weekend of the Mardin Biennial. Just 80 miles southwest of Hasankeyf, Mardin is famed for its picturesque array of honey-colored limestone buildings clustered around a hilltop. Many have been restored into tourist facilities that draw visitors from western Turkey and around the world who would likely not venture anywhere else in the country’s southeast. Alpar’s walking performance, “Looking at the Ruins,” served as a reminder that the ancient, multicultural heritage being touted in Mardin has met a much different fate elsewhere.

Even in Mardin, such touristification can also obscure harsh realities. During that same biennial opening weekend in 2022, a local festival was watched over by heavily armed guards on rooftops. Over the past decade, Kurdish politician Ahmet Türk has been thrice elected mayor of Mardin — and thrice replaced by a government-appointed trustee, a undemocratic process that has spread from cities in the southeast to other parts of the country. (Last year, Türk was sentenced to 10 years in prison for alleged PKK membership; he remains free pending appeal and was in fact part of recent government negotiations with jailed PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan that resulted in an agreement to lay down arms and disband.)

One of the photographs in the Possibility and Probability exhibition, part of Alpar’s “What Seeps in from Outside” series (2016–2025), zooms in on a surveillance camera perched on the corner molding of one of those traditional Mardin-style buildings, showing how the local architecture itself is engaged in constant monitoring of the populace. Another piece, “Resistance of Opacity” (2025), comprises a grouping of stainless-steel-coated souvenir renderings of Mardin landmarks, emphasizing how such heritage is often stripped of its specificity and context when packaged and sold for tourism, sidelining or erasing the people who inhabited the place.

The themes of collective memory, how histories are created, and who gets to tell their own stories link Possibility and Probability and Stone Shell Silent with Alpar’s earlier projects photographing the struggles and resistance of Turkey’s LGBTQI+ community. The artist’s vivid series on queer nightlife and Pride events focus on how marginalized individuals create spaces of possibility, safety, and self-definition despite increasing political pressure and homophobic rhetoric at the highest levels of government.

An exhibition of Alpar’s photos of Pride events around Turkey was itself cancelled as part of a government ban on Pride Week events in 2019; the artist, who has described their photography and activism as “intertwined processes,” instead staged the show guerilla-style outdoors. Two years later, when a government-appointed rector at Istanbul’s prestigious Boğaziçi University nixed a similar exhibition, students carried Alpar’s images aloft in protest.

The current political climate in Turkey has led to pervasive self-censorship across broad segments of society, including in the cultural community. Alpar is not among those who have shied away from potentially troubling topics. Neither is Depo. A project of the nonprofit cultural institution Anadolu Kültür, the venue for Possibility and Probability is one of a dwindling few artistic spaces still willing to host shows that touch on hot-button issues such as minority rights. But the price for the organization’s commitment to democracy and diversity has already been a heavy one.

Anadolu Kültür founder Osman Kavala, a businessman-turned-philanthropist, has been in prison since 2017, serving a life sentence without parole. He and other civil-society figures associated with the organization were convicted in politically motivated trials for their alleged roles in the Gezi Park protests, which were determined by the court to be part of an “attempt to overthrow the government.”

Kavala had already been behind bars for more than four years when he was spotted on the streets of Istanbul in late 2021 — in an oversized photograph carried by Alpar as he walked through the city to remind the public of the imprisoned figure’s plight. The performance piece, titled “Among Us,” referenced the freedom that Kavala could no longer enjoy and — by traversing parts of the city affected by gentrification and vanishing cultural heritage — some of the causes he supported through Anadolu Kültür.

Four years later, Kavala is still in prison, and calls for his release seem to grow ever-fainter. So too for jailed Kurdish politicians Selahattin Demirtaş and Figen Yüksekdağ, the former co-leaders of an opposition party that won 13.1% of the national vote in 2015 parliamentary elections. Since mid-March of this year, the prison ranks include Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu and many of his top appointees — along with many regular citizens who protested against these latest arrests.

It’s not just political opposition that can be dangerous; alternative narratives can be too. Cases of forcible disappearances in the southeast during the 1990s are still unresolved 30 years later and the organizers of weekly vigils calling for justice and accountability have faced prosecutions, bans, and police violence. Last year, an independent radio station had its license revoked after a guest mentioned the Armenian genocide, a description of historical events in 1915 that the Turkish government still disputes.

The final work in Alpar’s exhibition is a framed sheet of rusted steel engraved with its title, the words “The Secret Everyone Knows” (2025). Quiet yet forceful, it speaks both to the sense that past and present injustices are at risk of disappearing behind a veil of silence — and the potential for them to spark renewed action in the future.

Alpar’s show Possibility and Probability, curated by Melih Aydemir and Yıldız Öztürk, is on view at Depo in Istanbul through 5 July, Tuesday to Saturday, 11 am to 7 pm.