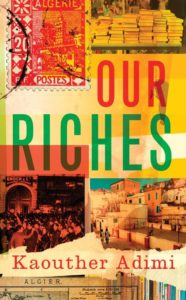

Feurat Alani, a novelist of Iraqi descent, succeeds in capturing the connections between two disparate cultural spheres.

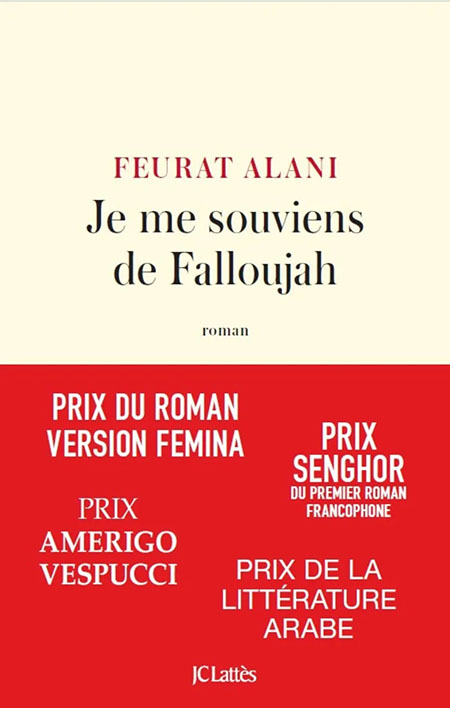

In his critically acclaimed, award-winning debut novel, the French writer and journalist of Iraqi descent, Feurat Alani, explores his father’s history in order to “live precariously through the memories of his remembered loved one.” It is the captivating story of a child from an immigrant background, who finds his voice and discovers his identity amidst the dynamic environments of two cities, two languages, and two cultures.

“Oblivion is the true shroud of the dead,” opens the debut novel, quoting George Sand. The name of the author is a reference to the Euphrates River which in its lower course encompasses the region of Mesopotamia, where the writer’s father, Rami, in a display of masculinity, nearly drowned — a short while before he lost his mother. Mother, I crossed the Euphrates for you. I swam with you atop my head in hopes of drowning your wounds, says the refrain of a popular poem in Fallujah.

In room 219, ensconced in a hospital in the Paris suburbs, Rami battles with cancer and partial amnesia, as he tries to recollect fragments from the early chapters of his life. The ones before the exile, about which he has always remained silent. Did I succeed in life? is the challenging query he presents to his son. In order to address this question, Alani will make efforts to reconstruct Rami’s memory, whereby in turn he too, will reveal all that he is aware of.

“In that hospital room, illness changed everything. It all became urgent and necessary. From then on, only the fundamental basics remained. The story of a man. The hope of a son. The transmission. Memory. That evening, I started at the beginning. I bought him a notebook. On the first page I wrote down some names, just as he had done for me long ago. The first: Euphrates.”

Between reality and fiction

And so, Feurat Alani became a writer. He was born in France in 1980, and initially served as a senior reporter for French media organizations in Baghdad prior to establishing his own production firm. His documentary Iraq: the sacrificed children of Fallujah (2011) won awards at multiple film festivals.

In 2019, amidst social unrest in Iraq, preceding its descent into a profound political crisis, Alani won the prestigious Albert-Londres prize, for his first graphic novel The Perfume of Iraq (Nova/Arte éditions). The jury characterized it as “foreign literature” due to its unique and unparalleled form: It consisted of one thousand tweets, each comprised of a paragraph containing 140 characters, all of which were posted during the summer of 2016.

This was soon followed by another graphic novel, Fallujah, My Lost Campaign (Les Escales, 2020), in which he reminisced about his childhood in a city that gained notoriety for being conquered and destroyed by the Islamic State in 2004.

The English translation of I remember Fallujah, due for release in September of this year, has already received the French Femina Novel Prize, the Senghor Prize, the Arab Literature Prize and the Amerigo Vespucci Prize. In this debut novel, the narrator endeavors to reconstruct his father’s past, in Iraq, in comparison to his own story, employing a reflective approach akin to a mirror game. “It seemed natural for me to describe the commonalities and differences in the violence or injustice between the two stories, those of a father and a son,” confided the author during an interview with The Markaz Review.

What distinguishes this work from its predecessors is that Feurat Alani does not feel obligated to strictly adhere to factual reality in his writing. “I like this freedom, being able to keep a porous border between reality and fiction which nourish each other.”

Memory is a fallible cognitive process that operates in conjunction with the truth, while words serve as mere representations of factual information. I didn’t betray you, Rami. I talked about your dream, father, the one you were unable to fulfill. The one that took me thirty years to achieve. We engaged in dishonesty possibly to facilitate uncovering the truth that had been inhibited by modesty. Yes, father, you passed on your silence to me. And silence is neither a truth nor a lie.

However, when composing fiction, Alani is unable to resist maintaining his journalistic instincts. Additionally, the narratives of Rami and Euphrates are interspersed with the historical context of Iraq that include landmark events, such as the first and second Gulf Wars and the embargo, which provide the backdrop to this personal story. This context allows us to understand what is happening in the lives of the characters.

On the night of March 19, 2003, everything changed.

At home, we were all gathered in front of the TV set. The ultimatum issued by George W. Bush had just expired. News channels around the world were tuned to Baghdad. We all remained silent, watching for the first bombing, for the slightest flash in the sky over the Iraqi capital. For several weeks already, my parents had been worried. The question of post‐Saddam was difficult to ask. It seemed impossible to them. The dictator could not be removed after so many decades of terror. My father, although a victim of Raïs, contested this invasion. He perceived the political ramifications of American deceit.

From Paris to Baghdad

The wars in Iraq have displaced entire populations, whereby thousands of Iraqis can no longer return to their country. “This tragedy is reminiscent of that of the Palestinians and other countries in the Middle East,” notes the author.

My father harbored a silent dream. To succeed in a life away from Iraq. This dream was shattered in the 1970s at the Paris sub-prefecture.

Mister, if you don’t collaborate, don’t dream.

This dream was contained in a small rectangular piece of plastic. A political refugee card brandished by one of the agents. The exchange was brief.

By choosing to exile himself in France, the fate of Rami’s father takes a divergent path. The man views the decision as a societal descent. Formerly employed as a guide for foreign delegations at the Ministry of Youth, he now finds himself selling postcards on the streets, in a predicament similar to that of his Algerian peers.

Like Ali and the others, he sold postcards to tourists. The square in front of Notre‐Dame was one of the most frequented places in the world. My father had a difficult job. He was required to walk the city streets regardless whether it was under a scorching sun, or through the harsh and unforgiving cold of Parisian winters. He had to exercise discretion at all times and be prepared for apprehension by the authorities.

However, his son Feurat felt differently. In contrast to the predominant North Africans and Portuguese in his neighborhood, he and his family represented a unique minority from a distant location. A minority within a minority.

When people asked me about my origins, I answered the only way I knew: I am from Iraq. Kader, who was originally from Morocco, had already asked me about this:

—Iraq? What is Iraq? Is that Arab? You couldn’t be Moroccan or Algerian like everyone else? It’s so weird, you’re not normal.

Like many children of immigrants, Feurat Alani was forced to learn a language that was not native to his country of birth. At a young age, he had to integrate the Iraqi dialect spoken in his household with the French language acquired at school, which ultimately became his primary form of communication, and in a sense his mother tongue.

My father didn’t travel the world. It came to him. Everyday, he walked the cobblestones in front of Notre‐Dame in Paris to sell postcards to tourists. Every evening, he came home exhausted, sat on “his” chair, silent, with a few vegetables, a bottle of wine and his Walkman headset plastered to his ears.

Juggling his home culture, which included Arabic literature, a poet father, and Iraqi maqâm music, with his education in a French school focused on literature and the classics, presented a significant balancing exercise for Alani. We lived in a tiny apartment located in the suburbs of Paris, situated on the first floor of a dilapidated white building on the outskirts of the Cité des Tilleuls, which was devoid of even the slightest lime tree (…) We were on the outskirts, in a ZUP, opposite a freight train station. Every evening, I fell asleep lulled by the endless convoys of goods that made my bed shake. This dormitory town served merely as a passing point where no one ever stopped. Like the trains, we too were in transit.

Nevertheless, he considers: “We, from immigrant backgrounds, are more fortunate than others because of the wealth that surrounds us. I was overwhelmed with riches.” Far from shying away from comrades immersed in French culture, who were benefiting from the facilities that children from immigrant backgrounds didn’t have access to, Alani instead regards his position in both worlds as an opportunity to broaden his global perspective. “I faced challenges. I was looked down upon, asked to return back to my place of origin. Nevertheless, I still felt at home in Paris,” he affirms.

I considered the haphazardness of trajectories: despite my birth in Paris, it is conceivable that I could have been born in Fallujah, a city I had never set foot in. It seems my name should have been on that list. No one chooses their place of birth. Life always begins with an injustice. Did we really have a choice? From then on, a strange feeling never left me again. I can’t tell if it was guilt at being lucky or regret at an unknown life that was normally predestined for me.

This cultural duality provided opportunities for gaining insights into the world and the nuances of language. It proved to be a valuable asset for Alani when he chose to pursue a career as a journalist. “I found my place in journalism,” he says. “When going to report abroad, you have to deal with people who are used to seeing different perspectives.”

After residing in Paris, his hometown, and Dubai for a number of years as a journalist covering the region, Alani today believes that he has severed all connections. “My true home is writing,” he proudly proclaims. “Paris is for me a little Baghdad. It’s the same type of town, with a river flowing through the middle. When I am immersed in the process of writing, I often draw parallels between the two.”

As a writer of Iraqi descent residing in Paris, Feurat Alani is able to bridge the gap between two distinct cultures, as he strives to capture their essence with precision and thoroughness.

I can now answer your question. Yes, you have made a success of your life – mine is just an illusion compared to yours. Where your dream failed, I dreamed in turn, I know who I am, I know where I come from, thanks to you, I emptied my invisible suitcase of my bad dreams. I understood that rather than letting time slip away into nothingness, we must retain it, inscribe it into memory, write it and speak it, perhaps make of it what is most beautiful. in this existence. Live forever through the one who remembers.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)