Leaving aside impassioned declarations, what role has Paris really played in the creation and dissemination of Arab literature? As something that reveals, perhaps, more than “makes,” writers and intellectuals, a vision that contributes above all to the myth that Paris aims to maintain. An exclusive excerpt from Coline Houssais’s Paris en lettres Arabes (Actes Sud 2024).

Coline Houssais

Translated from the French by Lina Mounzer

April, 2022, in the branch of a bakery chain in the La Défense shopping center. Before me is a small man with woman’s hands, with a liveliness of body and mind that seem to belie his ninety-two years. At once praised for his literary output and scorned by some for his political stance, Adonis is unquestionably a major figure in contemporary Arab poetry. The meeting almost didn’t take place; a few weeks earlier, an initial telephone exchange had begun like this:

“Hello, I’m calling on behalf of […] because I’m working on a book about Arab writers and poets in Paris and…”

“You can leave me out of it, I’m not an Arab poet, just a poet!”

From gathering points for each community to places where humanity in its entirety mingles, Paris opens its arms wide enough to welcome whatever pieces of home we might have left elsewhere, and with that same gesture also introduces everyone to the world.

Perhaps for those who aren’t from Paris, there is a constantly renewed sense of wonder at the encounter with Paris, that fascination of the periphery with the center. Beyond the abundant literature that deals with this phenomenon of provincial blooming upon contact with the capital, from Stendhal to Balzac and Maupassant, the myth of that Paris that creates artists and thinkers goes beyond the borders of France to resonate in all the corners of the world. Paris inspires, and not just those who have come to describe it. First, there’s the creativity that’s always stimulated by a physical distance from the literary object. Then there’s that cultural attraction that the City of Light has always held for Europe in general, and then for the whole world from the period of the Enlightenment onwards. And finally, there’s a self-fulfilling prophecy that comes to pass for all those who come to sample — and therefore contribute to — this Parisian myth.

The invisibility of Arab literary figures over the centuries has led to them positioning themselves with their backs to Paris, drawing on the intellectual and personal experiences the capital has to offer while remaining resolutely focused on their countries of origin.

The relationship between Paris and its writers is first and foremost a story of representation: Like many living myths, the City of Light is loaded with symbols that belong only to those who formulate them. For many, Paris exists before one arrives in Paris, an idea only reinforced by the long presence of a genealogy of Arab intellectuals within its walls. One’s arrival in Paris is motivated by the desire for Paris as both a physical and imaginary space, a place of inspiration in which to discover oneself as a writer. As a cultural reference and source of inspiration, Paris encourages the writer to position herself in relation to it, as the transition takes place from a dynamic of demand, where writers are invited to come and dispense their knowledge, to a dynamic of supply, where their spiritual heirs are invited to France to be nourished by the latter’s contributions to culture. By contrast, the invisibility of Arab literary figures over the centuries has led to them positioning themselves with their backs to Paris, drawing on the intellectual and personal experiences the capital has to offer while remaining resolutely focused on their countries of origin. It’s an approach that applies equally to those just passing through Paris as those who have put down roots here, particularly those long-term exiles and those who, having grown up in France while claiming a heritage from the other side of the Mediterranean, must perform the sometimes delicate dance of dual identity through their own flesh and blood.

Leaving aside impassioned declarations, what role has Paris really played in the creation and dissemination of Arab literature? As something that reveals, perhaps, more than “makes,” writers and intellectuals, a vision that contributes above all to the myth that Paris aims to maintain. More often than not, the seeds have already been planted: at most, they germinate in the City of Light before bearing fruit back home or in a more familiar environment, in a strange parallel with the personal development of the writer or intellectual who, as a young adult on the banks of the Seine is simply affirming the appetites and interests awakened earlier in his or her country of origin, when they will go on to experience intellectual maturation elsewhere. Paris is thus the antechamber of Maghrebian and Levantine thought and literary creation; a sounding board, a ground for experimentation in both form and content. Paris also contributes to the very idea of an Arab literary and intellectual “whole” through the fact that it operates as a Maghreb-Middle East junction both on an organic and institutional level, particularly at a time when, more than a thousand years after the collapse of the Umayyad Empire, a new political impetus at the turn of the 20th century aims to unite the peoples of the region against European and Ottoman imperialism. From outside the Arab world, France is an anchor that helps bring this construction to life, and thus represents a place of balance and contact, a “point of view” between these two geographical and cultural subsets, whose impact is felt beyond France.

Conversely, what role do Arab writers and intellectuals play in Paris? For a very long time, they acted as go-betweens, honorable but anonymous assistants and, in some cases, foils. With their mere presence, however brief, they helped contribute from the outset to the intellectual and artistic ferment of the City of Light, helping to make it a capital, and enabling it to shine like a beacon in the distance for those literary figures steeped in French culture from generation to generation in their own lands. The story of Paris as an intimate, cultural and linguistic part of a certain Arab literary self, the consequence of centuries of mutual exchange and presence, both tangible and intangible, is nevertheless the story of an imbalance that is never more visible than through the guises of an oft-fantasized “Orient,” the representations that have been made of it throughout the years, even by those who have never been there. This historical imbalance gives rise to a double paradox. First, the French fascination with Arab culture and contempt for those who embody it. Then, the Arab paradox of seeing France as both the colonial monster to be fought and the social and political model to be followed; frequently scorning France as the metonym of power but loving Paris, in a strange dichotomy in which the latter seems as though it had been extracted from the territory in order to exist elsewhere. Does the myth of Paris matter more than reality? This double paradox, coupled with a kind of mutual trickery, whereby each uses the other and the representations we make of them — and that they make of us — to achieve his or her collective or sometimes more personal ends, leads to a special relationship between Paris and Arab writers. A real attachment tinged with conflict. In short, a certain neurosis. What could have been the title of this book: A Very Delicate Neurosis.

Maison de la Poésie, December 2023. Samar Yazbek (b. 1970) appears on screen, filmed by Rania Stephan. Turning towards the camera, she nods towards the shelves of books behind her:

“My library is growing. If I start building up a library here in Paris, without buying e-books or borrowing books, I’m staying in Paris. It’s my identity now. I’m staying here. I have a library in Syria, only. Ask me a question!”

Yazbek, like so many others, fleeing the endless repression following the Syrian revolution, arrived in Paris in 2012 without speaking a word of French.

Over the centuries, Paris has, for many, been the place to acquire personal, intellectual and artistic maturity. An experience hinging on an academic or professional career and limited in time — a few months, a handful of years at most. A necessary passage through a focal point of thought and creation before returning home. Even today, the City of Light is the first destination to which to flee, a hand held out in a hurry and seized by survival instinct, even if one will eventually continue one’s journey beyond the Île-de-France region or abroad.

Paris is a relay city, an initial base, a major interchange before leaving for other horizons, sometimes more friendly, certainly less laden with reminders of the lost country. When the Palestinian Mahmoud Darwish finally returned to France for an operation in 1998, in his hospital room he wrote “O death, wait until I pack my suitcase.” The Iraqi Saadi Youssef (1934-2021) wrote Qasâ’id Bârîs (The Poems of Paris) during his time flitting between a number of European and Mediterranean cities before finally dying in London. With the post-independence period, however, came the era of long exiles, reflecting the instability of the regimes people were fleeing or their unwillingness to remain at home in the face of rising religious conservatism or repeated economic and political crises: in the 21st century, the new exile is one of weariness, and Paris the antechamber of a return that never comes. Not to mention the years that slip by without realizing it, for those who “have tasted the cancer of France,” end up in “temporary stays that last thirty years” and who, not initially intending to stay, will inadvertently spend most of their lives there. Living in Paris for an entire lifetime, or even from one generation to the next, is nothing new, as Napoleon’s Mamelukes attested, even then creating “two interlocking spaces.”

Today, however, Paris is a place where people go to grow old or to give birth, and this dual identity, acquired or innate, leads to new dynamics. Sometimes, it’s also a place where people go to die, lifting their anchors in the twilight of their lives to sail off and join relatives who immigrated earlier.

There are many who maintain a pendulum-style relationship with Paris, swinging back and forth, in each return to the banks of the Seine seeking the promise of a definitive reconciliation with the City of Light, or the renunciation of what one has gone elsewhere to seek. In the end, with one foot in each place, we create an ideal city made up of two imperfect halves. This pendulum movement, slow in the case of Algerian writer Assia Djebar (1936-2015), who spent three long periods in Paris, has accelerated with the added ease of travel, which allows us to flit back and forth ever-faster while at the same time creating a gap: we might be physically present while feeling ourselves to be mentally elsewhere, only to end up being nowhere except in an intermediate space that belongs only to ourselves and to others who, like us, are in the same sort of situation. Even when the physical comings and goings cease, the internal pendulum continues to swing, in a movement exacerbated by the development of communication technologies that make it possible to exist in one’s place of origin without actually being there. Or to live in Paris with one’s heart elsewhere. Not yet — if ever at all — from this place, no longer from that place, as evidenced by the gulf that sometimes becomes obvious when meeting with old friends from back home.

This state of affairs reflects the deep and intimate ambivalence of individuals who are now too French in the eyes of their own country, but still too Arab in the eyes of France, such as the Franco-Lebanese writer Sabyl Ghoussoub (b. 1988), who makes this dual identity the basis of his novels, or the painter Chafik Abboud, who sums it up like so: “I’m no longer Lebanese, I can’t be French. Nationality: foreign, and in general I’m fine with that.”

Paris as a piece of a puzzle, the key to a mystery for those who have trouble finding their place, no matter which side of the Mediterranean they were born on. It’s a solution that allows a person to avoid a total break with the Arab world, or to flee from it, knowing — or even hoping, as if suffering from Stockholm syndrome — that it’ll reappear around the corner in Paris. In the words of Wassyla Tamzali, “when an Algerian arrives in France, he doesn’t leave Algeria, he doesn’t go to a foreign country.”

Four centuries after its great beginnings, the relationship between Paris and Arab writers remains tinged with ambiguity, so disconnected from reality is the city’s symbolic charge. The idealization of the City of Light continues to suit everyone: some continue to see it as the embodiment of a universe both foreign and intimate, as well as the symbol of a modernity of which they automatically become a part by physically being there. Generally speaking, the experience, at least in its expression to others, is a positive one: those who come most often expect to find what they’ve come for — beginning with a confirmation of what they’ve been taught and what others say they’ve found — thus becoming part of that intellectual and artistic genealogy of the city.

Syrian playwright Sadallah Wannous (1941-1997) lived in Paris during three periods of his life. An assiduous visitor to Parisian theatres — especially during his first two stays — and fully aware of the ambiguous relationship between his native region and the West, he lived in a kind of bubble, caught up in a desire to dissect European theater and draw from it only what he could sublimate into contemporary Arab theater without outright imitation. Twenty years after its premiere in 1993, his masterpiece “Rituals for a Metamorphosis” became the first Arab text to enter the repertoire of the Comédie Française. Thus, for a very large proportion of those who come to stay within its walls, Paris exists even before they ever set foot here. And one’s arrival, when it finally comes, will not feel so much like a discovery as it will a reunion.

For those who “have come to make a concrete utopia,” or who came seeking “the refuge of the universal,” leaving Paris, especially to return to a country necessarily tarnished by the image they’ve retained of it, would feel like failure. This smokescreen enables France to sidestep its colonial past and position itself as the seductive spirit of the Enlightenment that preceded it and which is said to have survived it. The deception is cordial and fully assumed by both sides. But few are spared the confrontation with reality. As Ali Benmakhlouf puts it: “In forty years, I’ve been able to encounter French culture, but never French society.” Meanwhile Adel Refaat, over the course of his sixty years in Paris, has “never known anyone who wasn’t intimately disturbed by the France he saw, and whose reality was thus transformed.” He also points to the experience of women writers of his generation, whose “encounter with Paris differs” from his own, owing to the difficulty of obtaining from those left at home the same freedom and esteem reserved for men as well as a necessarily different way of occupying time and public space, where so many are able to elaborate their thoughts and socialize until late at night in cafés.

Beyond the disappointment inherent in any fantasy, and the discovery in a foreign land of codes we thought we knew so well from books, perhaps the most brutal reality is that, however steeped in France they may be, foreigners remain apart from it, contributors to a great national intellectual novel from which they are excluded on arrival. Lost illusions have no shortage of victims, and for every account, like the half-hearted one by Misr al-Qâhira co-founder Adib Ishaq or Vénus Khoury-Ghata’s novel, Une maison au bord des larmes, inspired by the story of the author’s brother, who, shattered by his Parisian sojourn dies in a psychiatric hospital during the Lebanese civil war — how many fall silently through the cracks?

In Arab literature, the City of Light is ultimately only directly present when the author stages themselves inside it, using a first person narration to tell a story whose outlines are sketched out in this book: are we only talking about Paris to talk about ourselves? For some few exceptions, ambiguity taints the appeal of a city that, in the end, doesn’t always welcome those it seduces. In La Vie lente by Moroccan author Abdallah Taïa (b. 1973), who has lived in France since 1999, the narrator ends up confiding in a police inspector on rue de Turenne. His monologue reveals a life made up of ups and downs, as well as a portrait of a Paris that is sometimes nightmarish, but in which the eternal seduction of a dream-city nevertheless remains visible.

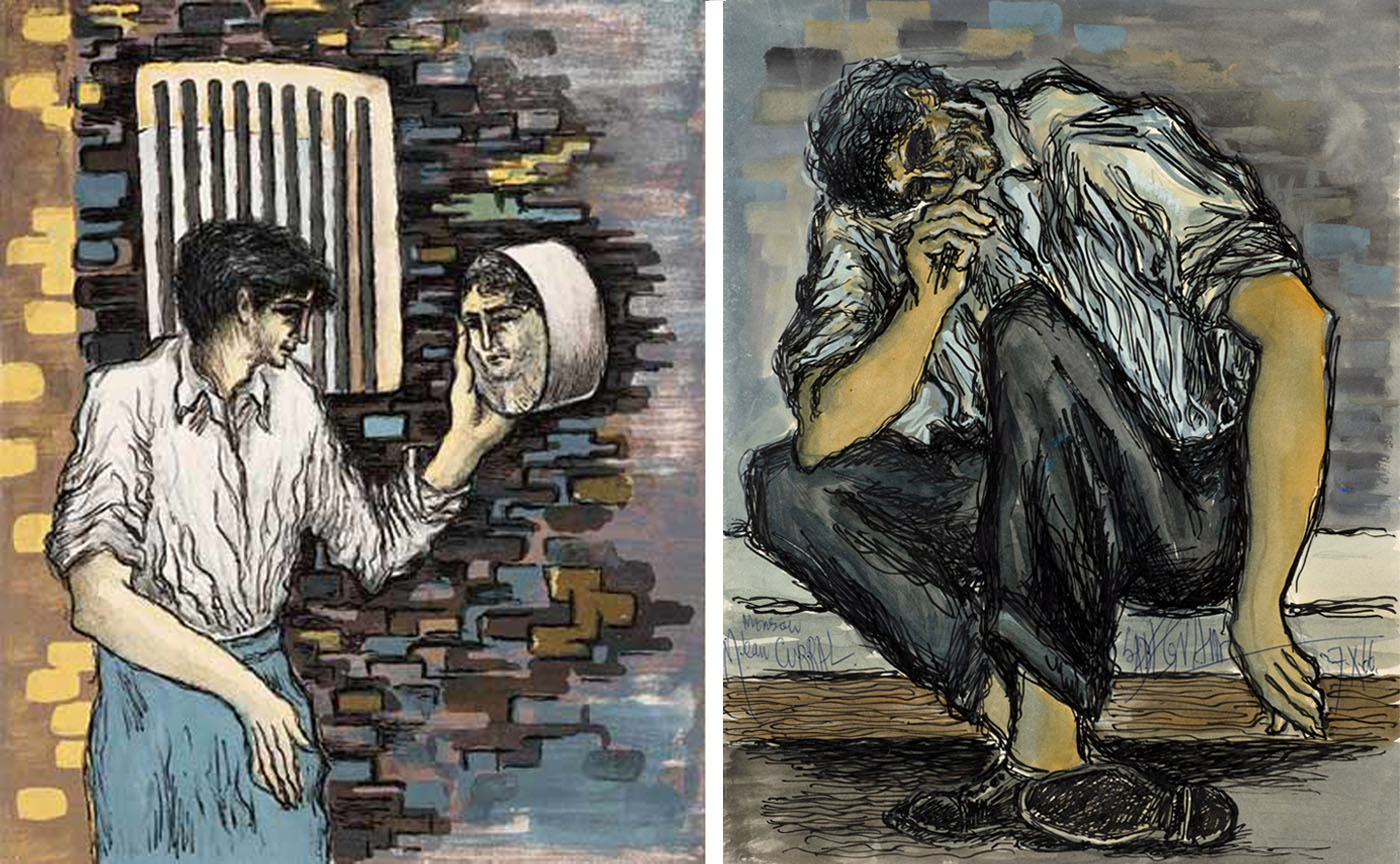

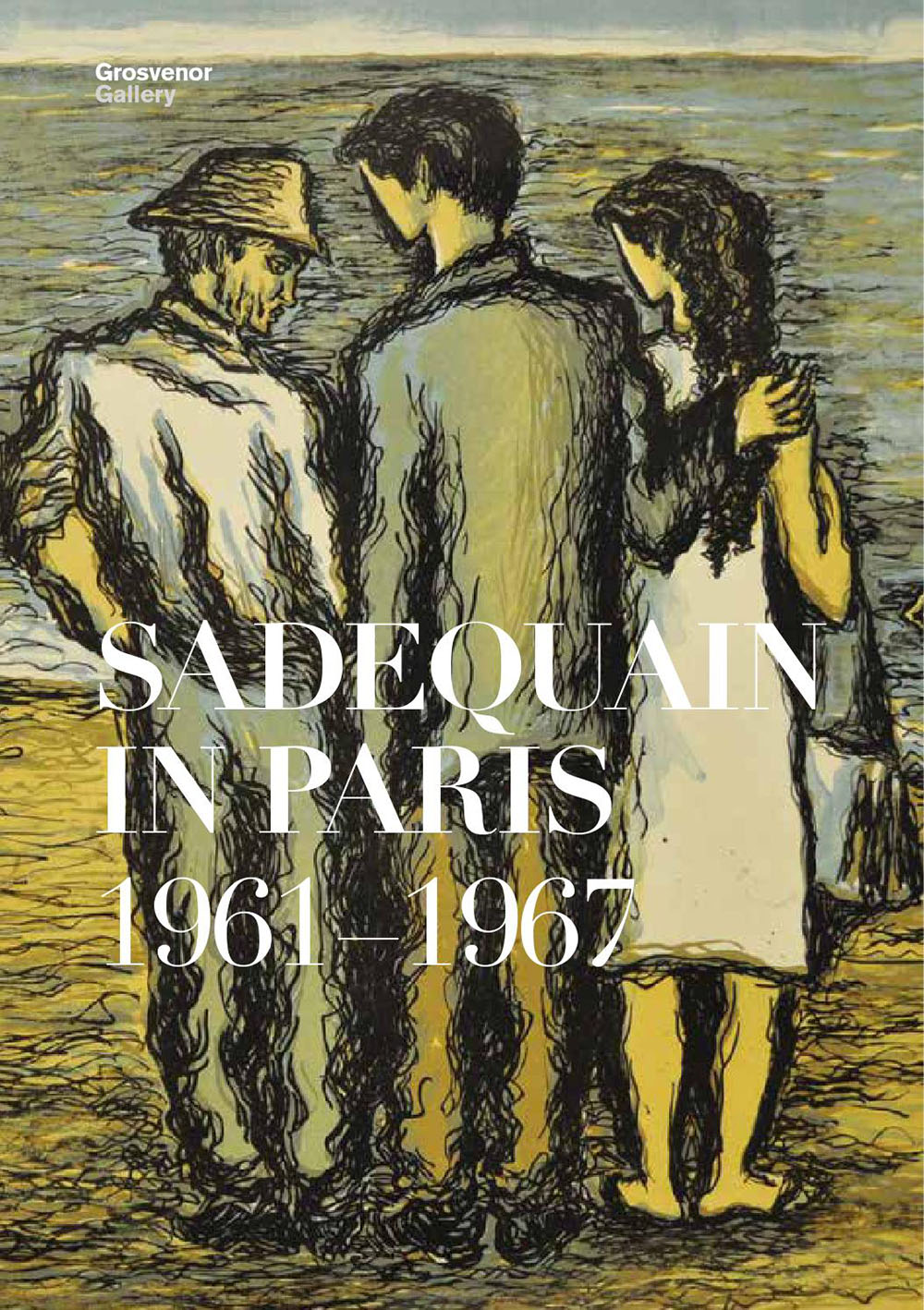

After La Nuit de l’étranger, whose main character is a young Tunisian worker in Paris, La Voisine du cinquième, the eleventh novel by Habib Selmi (b. 1951) depicts the bourgeois daily life of a university professor of Tunisian origin, a distant echo of the author’s own life as a teacher of Arabic in preparatory classes and a resident of the 11th arrondissement, in a house incidentally just across the street from that of his publisher, Farouk Mardam Bey. In addition to stories that glorify the city and serve above all those who are at its center, whether travelers or intellectuals, these examples show a Paris with a tarnished aura. How can one be oneself in relation to one’s country of origin in a city that is more a setting than a character? Living in Paris becomes a particular way of living out one’s dual literary identity, so much so that the City of Light has historically always been part of a cultural and intellectual frame of reference for the Arab world, particularly for certain countries.

In spite of this, Paris offers a cozy setting into which one can deeply plunge, and where one can “experience a chosen solitude more easily than elsewhere.” With some distance, the relationship with the homeland left behind becomes easier, sometimes to the extent of becoming rewritten entirely, where it is unacknowledged or on the contrary claimed as an integral part of the process of literary creation. Such is the case of Lebanese novelist Souhaib Ayoub (b. 1989), who declares: “If I were in Tripoli, I couldn’t write all this; I’m not a historian, and I need access to an imaginary world that develops thanks to distance.” Then he adds: “Paris has given me this invisibility… I’m a ghost who enters, searches and rummages everywhere.”

Though rarely absent, the country of origin remains permanent for some authors, like those few districts of Cairo for Albert Cossery, or conversely, for Vénus Khoury-Ghata, a place always acquiring new frontiers and “inhabited by this Arab world that recurs in [her] novels.” As for the exiles and the disappointed, they write about the world they would have liked to create at home.