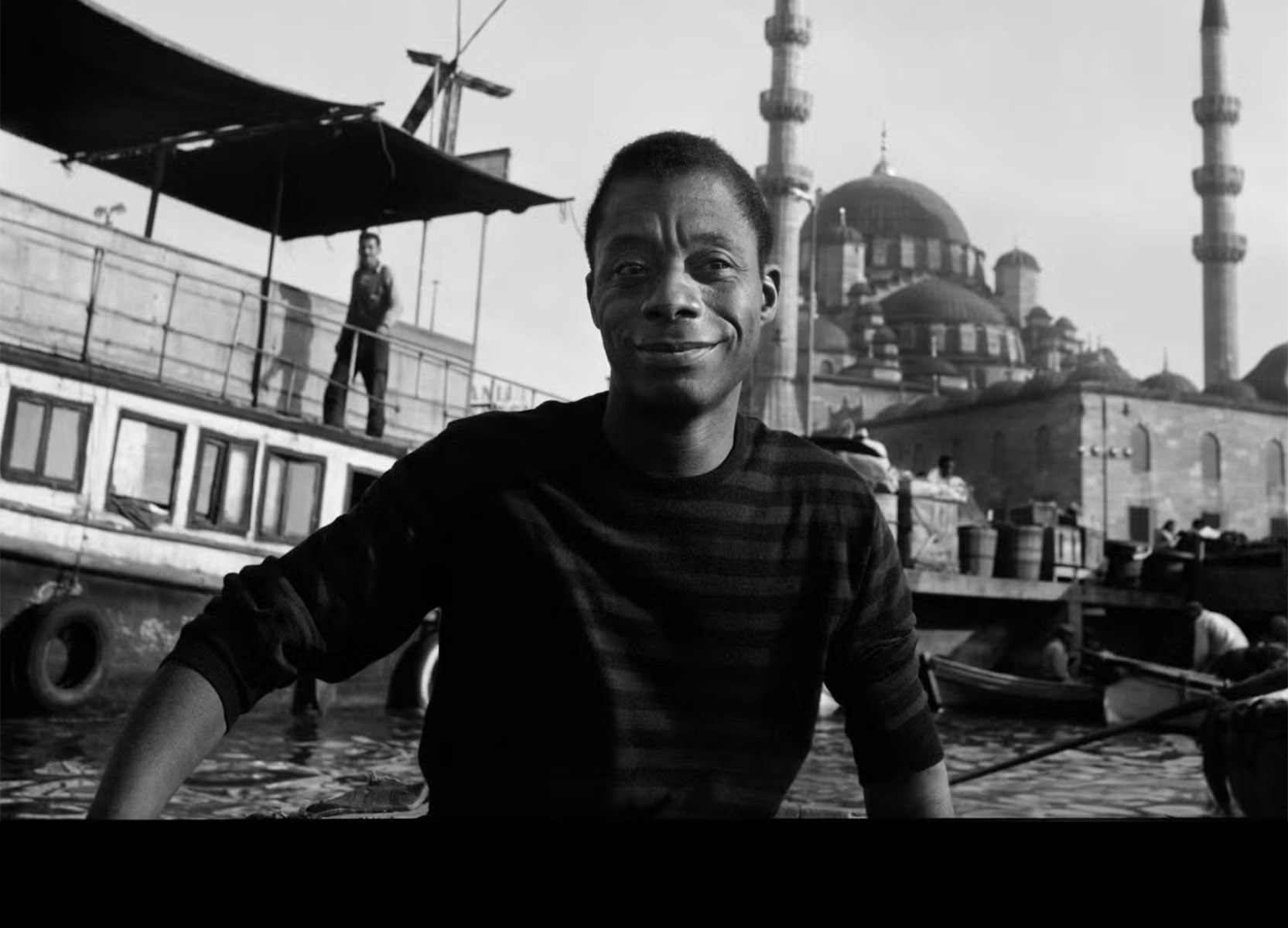

James Baldwin's chosen refuge in Istanbul led to a creative rebirth, notably shaping his vision of race, sexuality, and identity.

James Baldwin, a literary giant and fierce voice of the twentieth century, found a second home in Istanbul during a transformative decade from 1961 to 1972. While his voluntary exile from America is well-known, his time in Turkey — particularly his semi-residency in Istanbul — remains a lesser-told chapter, one that shaped his vision of race, sexuality, and identity in profound ways. In this city straddling two continents, Baldwin discovered a haven where he could breathe, write, and reimagine what it meant to be Black and queer in a world that often rejected both.

After a trip to Israel, Baldwin arrived in Istanbul for the first time in the fall of 1961. He had come at the invitation of his friend Engin Cezzar, a Turkish actor and Yale graduate whom Baldwin had met in 1957, at the Actors Studio in New York. That same year, Cezzar played the title role in Baldwin’s New York staging of Giovanni’s Room, marking the beginning of a long artistic partnership and a deep friendship that unfolded across theatre, film, and continents.

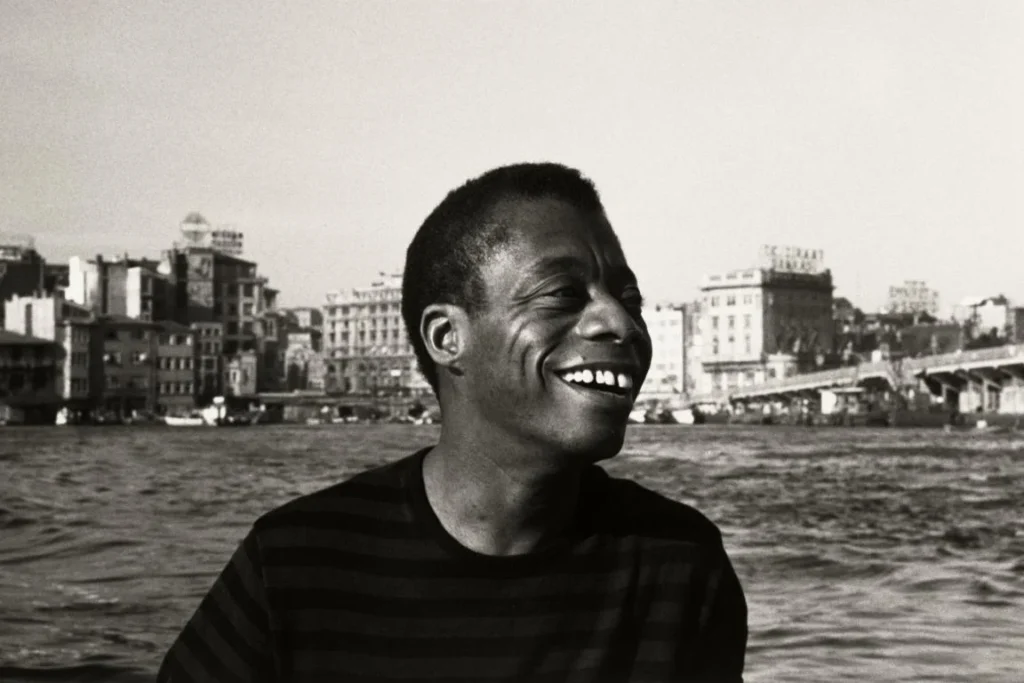

In his preface to Dost Mektupları, Cezzar recalls the night Baldwin appeared at his home unexpectedly — just as he and Gülriz Sururi were celebrating their wedding with close friends and family. Baldwin, he writes, arrived in a state of deep depression brought on by a prolonged writer’s block. After a few drinks, he fell asleep with his head on the lap of a Turkish actress he had met only hours earlier. During that first visit, Baldwin stayed nearly four months in the couple’s home, recovering, meeting Istanbul’s artists and writers, and wandering the city that would soon become a refuge.

In Istanbul, Baldwin’s pen found its rhythm.

By the time Baldwin sought shelter in Istanbul, he had already spent more than a decade living in self-exile in the south of France. In an interview with Josephine Baker, when asked why he left the United States in 1948, he answered simply: “I left because I was a writer. I had discovered writing and I had a family to save. I had only one weapon to save them: writing. And I couldn’t write in the United States.” The America he left behind was still shaped by Jim Crow laws and the systemic violence that kept African Americans politically and culturally invisible. Outside the newly desegregated military, the only sanctioned visibility granted to Black people came through racist caricatures and hypersexualized images produced by white culture. The early Cold War climate only intensified this repression. Black writers, artists, activists, and intellectuals — especially those associated with the political left — faced federal interrogations, harassment, intimidation, and persecution.

Like many other African American writers and musicians of his era, Baldwin searched for a safer place to work and imagine a creative future, and Europe became that space. But he never viewed crossing borders as a way to shed his identity or escape the realities of his country. Nor did he assume that any of his adopted homes were free of racism, sexism, or political coercion. For Baldwin, distance offered clarity: a vantage point from which he could see America more sharply, without being suffocated by its daily violences. In the opening scene of Sedat Pakay’s short film James Baldwin: From Another Place, Baldwin reflects, “perhaps only someone who is outside the States realizes that it is impossible to get out.” Later he adds, “One sees one’s country better from a distance… from another place, from another country.”

Magdalena Zaborowska, in James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile, states that Baldwin regarded “Istanbul as a neither-here-nor-there liminal space” that provided him with the necessary distance from the racial and political turmoil of America. The city, with its ancient Byzantine walls and layered history, also offered him “a certain silence, a certain privacy that is not, at least for me, to be found elsewhere.” Choosing not to learn Turkish, he preserved this solitude, engaging with the city’s vibrant life through the veil of translation, always an observer, always apart. Yet, this distance allowed him to see clearly, to weave the threads of race and queerness into his work with new depth.

This distance was not isolation but possibility. In Turkey, Baldwin encountered a society that did not frame the world in the same racial and sexual binaries he had always been forced to navigate in the west. As Zaborowska notes, Istanbul also became for him a “third space for queerness,” an in-between where categories blurred. Turkey in the 1960s was far from a utopia of freedom — politically turbulent and hardly progressive by western standards — but there were striking absences. No “black” and “white” as rigid racial designations that defined (and still defines) America. Homosexuality, though seldom named and often treated as taboo, was not criminalized. Same-sex relations existed as part of the social fabric, albeit in an Eastern way: visible yet unspoken, acknowledged but never claimed as identity. The public silence over homosexuality was usually contradicted by “the open and often deceptive homoeroticism among men, which took Baldwin some time to understand.” Baldwin needed this ambiguity, this silence, to carve out space for himself.

In Istanbul, Baldwin’s pen found its rhythm. The city became his creative crucible, where he completed his novel Another Country in the winter of 1961, marking its final lines with the city’s name — a rare gesture for him. Other seminal works followed: The Fire Next Time, Blues for Mister Charlie, Going to Meet the Man, Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, One Day When I Was Lost, and No Name in the Street. Each bore the imprint of Istanbul’s quiet embrace, a space where Baldwin could wrestle with America from afar.

His artistic journey took a bold turn in 1969 when Engin Cezzar invited Baldwin to direct John Herbert’s Fortune and Men’s Eyes at the Sururi-Cezzar Theatre, one of the first and most important avant-garde theatres in Istanbul, which Cezzar founded with Gülriz Sururi. Turkey was on the brink of another military coup, yet its cultural scene buzzed with daring experimentation.

The play itself was already charged. Set in a juvenile detention center, Fortune and Men’s Eyes follows young men brutalized by violence, repression, and desire. In Turkish, the play took on an even sharper edge. Ali Poyrazoğlu, who later starred in it, and Oktay Balamir, who worked at the British Consulate, translated it with a striking new title: Düşenin Dostu — “The Friend of the Fallen.” The phrase flips a Turkish proverb, Düşenin dostu olmaz (“The fallen have no friends”), into its opposite.

As Zaborowska points out, Baldwin must have been drawn to the parallels between Herbert’s characters — society’s unwanted children — and his own lifelong confrontation with questions of home, exile, and identity. Directing a play about white homosexual men for an Istanbul audience with no fixed vocabulary for either race or sexuality echoed Baldwin’s insistence on redefining and re-articulating the most difficult questions of human difference. He believed, too, that “Turkish theatre of the 1960s was more radical in many ways than American theatre,” and in Istanbul he had the freedom to try what would have been impossible on Broadway.

In a note for the theater company’s newsletter, Baldwin framed the play’s themes through Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard:

Fortune and Men’s Eyes is concerned with prison homosexuality in precisely the same sense that Chekhov’s play is concerned with cherry orchards. As Chekhov’s play ends, we hear … the sound of the axe beginning the destruction of the trees — the destruction of a human possibility doomed by human folly. The boys in Fortune and Men’s Eyes are, like those trees, cut down, and, in this case, before our eyes. The play, then, confronts us with the question of how people treat each other, and especially with the question of how we treat our children.

Working through a language barrier, Baldwin relied on journalist Zeynep Oral as his translator and production assistant. He forged a familial bond with the cast, calling them his children, as noted by biographer David Leeming. This intimate, inside-out directing style was new to the actors, sometimes unsettling, but deeply effective. Despite claiming little theater knowledge, Baldwin shaped Düşenin Dostu with more control than he had over his own Blues for Mister Charlie on Broadway.

Premiering on December 10, 1969, after a month of script study and six weeks of rehearsal, Düşenin Dostu became a sensation. Despite a brief state ban, it drew thirty thousand viewers in under two months. “There was considerable buzz around Düşenin Dostu even before it opened. […] Nothing, however, could prepare us for [it].” Even more telling are Reşat Kasaba’s retelling of how the Turkish audience seemed to absorb the play as if with a single, collective consciousness:

Some of us managed to overlook or ignore the theme of homosexuality that was at the center of the play and focused, instead, on the subject of young people in prison. Perhaps this was easier to relate to because it was becoming an everyday occurrence in Turkey in the late 1960s for high school and university students to be arrested for their political activism. For others it was the theatre that really mattered — the powerful staging and, especially, the tour-de-force performance of Ali Poyrazoglu who played the transsexual inmate Quennie. And for many of us, it was being the virtual company of James Baldwin that was the most memorable thing about the play.

When Baldwin agreed to direct Fortune and Men’s Eyes in Istanbul, he was fully aware that its central themes — homosexuality, homosocial tension, and the brutalizing architecture of the prison — would strike Turkish audiences with unexpected force. Its language was profane, violent, and unflinchingly intimate. Yet Baldwin sensed, almost instinctively, that Istanbul offered him a rare freedom, “a unique opportunity to explore some of the issues central to his own work,” he later said, “with no worries about either finances or domestic politics.” Speaking to Ali Poyrazoğlu in the theatre company’s newsletter, he reframed the play not as a provocation but as a diagnosis of modernity itself: “It symbolizes masculine loneliness in this century. This is a universal problem for everyone in our age. Since Turkey is also living in the twentieth century… I believe I will be able to handle this by my instincts.”

To the surprise of many, the production became the hit of the year, hailed as the first Turkish staging in the European wave of “Theatre of Horror.” It was also the first play to feature openly homosexual content in the Turkish theatre scene. Its success deepened as it toured the country, drawing enthusiastic audiences even in cities where such subject matter seemed most improbable — places such as Zonguldak, a coal-mining port town far from Istanbul’s cultural circuits. Poyrazoğlu believed that the play resonated because spectators instinctively understood Baldwin’s deeper point, that “the prison could be anywhere,” and that what they were witnessing was not an imported scandal but an anatomy of men and their own entrenched “culture of violence.”

Even as some critics and audience members attempted to sidestep the play’s open confrontation with homosexuality and homophobia, its very presence on the Turkish stage destabilized longstanding taboos. In a country where public discussion of sexuality — let alone queer life — was nearly nonexistent, Baldwin’s production catalyzed an unexpected and unprecedented public conversation about gender and sexual politics. Whether or not Baldwin calculated its impact, the play’s reception exceeded the expectations of everyone involved.

Yet this remarkable artistic moment, arriving near the end of Baldwin’s Turkish decade, passed largely unnoticed in the United States. Instead, some observers leveled insinuating accusations that Baldwin’s extended stays in Istanbul amounted to “sex tourism” or “sex exile” — charges that revealed far more about Western voyeurism around race and sexuality than they did about Baldwin’s Turkish years. He replied not defensively but by reaffirming his ties to local people, to the artists with whom he worked, and to the city that had given him the privacy and imaginative space necessary for some of his most important writing. Directing the play, he also turned the western orientalist gaze back on itself — operating from within a place long objectified by the west, a place he admitted he had once simplified in similar ways.

Through writing and creating, and through what he often called his refusal of all forms of domination, Baldwin carved out a private haven in Turkey — a site of both retreat and revelation. He reimagined exile not as disappearance but as transformation. He also discovered that the in-between could be a home where the fallen still had friends.