The iconic Moroccan folk songs and radical politics of Nass el Ghiwane were forged not in the Magreb but on the destitute streets of Paris in the 1970s.

In the fall of 1970, the Moroccan playwright Tayeb Saddiki took his troupe Masrah Ennas from the Théâtre des Gens on a tour of France to perform the group’s experimental take on North African folktales and oral traditions. In the troupe were a few young actors from Casablanca’s working class Hayy Mohammedi neighborhood, who contrived to overstay their visas after the tour’s end and Saddiki’s return to Morocco. Destitute and isolated, Larbi Batma and Boujemaa H’gour lived a life of intense deprivations on the streets of Paris. Batma would later describe stealing milk and eggs from doorways to eat, taking costumes from local theaters to keep warm, and sleeping in the metro tunnels. “In Paris there was torture.” He writes in his memoir, “Torture of a different kind, the torture of loitering and sleeping in apartment doorways or on the metro and running from the police.”

Yet something about the revolutionary currents sweeping France in the post-1968 era resonated with the two young Moroccan artists, keeping them in Paris despite the hardships. Eventually they fell in with Mohamed Boudia, an Algerian playwright and leader in the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Through Boudia, H’gour and Batma became enamored with the ideas of radical leftists like Che Guevara, George Habbash, and Mehdi Ben Barka. Boudia “loved us to a crazy degree, especially when we sang our revolutionary songs for him,” Batma recalls. “We spent three months in Paris living on the streets. Three months felt like three centuries. But during that time we wrote a number of things, zajal poetry and song lyrics, which would make us famous.”

Upon returning to Morocco later that year, Batma and H’gour founded a folk band called Nass el Ghiwane which would become the most successful and influential North African band of the 20th century. When they returned to Paris in 1976, they did so to headline a performance at one of the city’s biggest venues, the legendary Olympia Theatre.

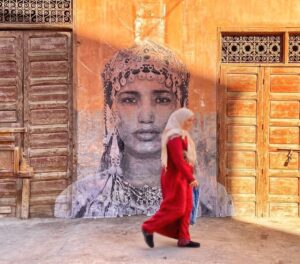

Nass el Ghiwane’s success highlights the importance of Paris as a central junction in the political, social, and cultural networks of North African history. In a postcolonial moment when political conflicts, particularly between Morocco and Algeria, made intraregional travel in the Middle East and North Africa increasingly difficult, Paris served as a meeting point for artists and intellectuals from across the region. Ironically, Nass el Ghiwane achieved success through a folksy, rural, and self-consciously nationalist Moroccan sound, which they actually formulated on the streets of metropolitan France. Paris’s centrality to the questions of national identity and artistic authenticity in Moroccan music demonstrates the increasingly transnational nature of North African political and cultural movements over the past century.

An Unexpected By-Product of Colonialization

Thanks to colonial networks of labor migration and material production, Paris has been an important artistic center since the very beginning of the record industry, in the early 1900s. The Paris-based Pathé Records, which dominated the early market in wax phonograph cylinders, produced the first commercial recordings of North African music, mostly from the classical Andalusian repertoire. European record companies built impressive distribution networks across North Africa, where intermediaries like the Algerian Jewish musician Edmund Yafil would both sell Pathé records and recommend local musicians for recording and distribution. In the mid 1930s, the rrways singer and rebab player Lhaj Belaid traveled from southern Morocco to the Baidaphon Records studio in Paris to create one of the earliest recordings of Moroccan Tamazight music.

Out of this group of recordings, the song “Ammudu n Bariz” (A Trip to Paris) praises the city of lights as a place where many Maghrebi immigrants first encountered the wonders of the modern world: “There are no more troubles, neither on earth nor at sea / He who wishes to travel has no more excuses / In the heart of Paris I had good company / Where you were all gathered oh chleuhs [Imazighen] / Chleuhs and Arabs all happy.” This reference points to Paris’s importance as a meeting point for people from different ethnic groups across the Middle East; the song’s spoken introduction (a common formality of early recordings) suggests that the legendary Egyptian singer Mohammed Abdelwahab was in the studio when Belaid recorded.

In the decades following World War I, tens of thousands of Maghrebi immigrants settled in Paris, creating a trans-Mediterranean market for North African music. In his book Recording History: Jews, Muslims, and Music across Twentieth Century North Africa, Christopher Silver details how Paris became an important center for Maghrebi musicians between the 1930s and 1950s. Rising stars like Salim Halali and Louisa Tounsia sang frequently at clubs like Au Petit Marseillais in the Marais and El Djazaïr in the Latin Quarter. Recording in the Pathé studios in 1939, Halali, an Algerian Jew, gave voice to this immigrant community’s melancholy sense of exile on “Arja’ l-biladak” (Return to Your Country). His plaintive voice calling: “Return to your country man / Why do you remain estranged?” was popular both among immigrants in France and back home in North Africa; it was considered so subversive that Vichy officials in Morocco banned Halali’s record in 1942.

Given this history of dense commercial, technical, and musical networks overlapping in Paris, it seems almost inevitable that the city would be a launching point for the Ghiwani revolution in North African music in the 1970s. The young Moroccans Larbi Batma and Boujemaa H’gour were forced to return to Morocco in 1970 when French police began investigating Boudia’s activities with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Larbi even claims that he and Boujemaa were intended to participate in the PFLP bombings undertaken by the Moroccan sisters Ghita and Nadia Bradley in Tel Aviv later that same year. The trip in France would have a permanent impact on the art and ideas of Nass el Ghiwane, particularly through the songwriting of Boujemaa, who “went from a world of freedom, of democracy [in France],” recalls his friend Miloud Oualla, “to one of backwardness and legend that we were living here [in Morocco].” The exposure to revolutionary ideas from across the Middle East that the pair received in Paris catalyzed an artistic process which would lead them to massive success.

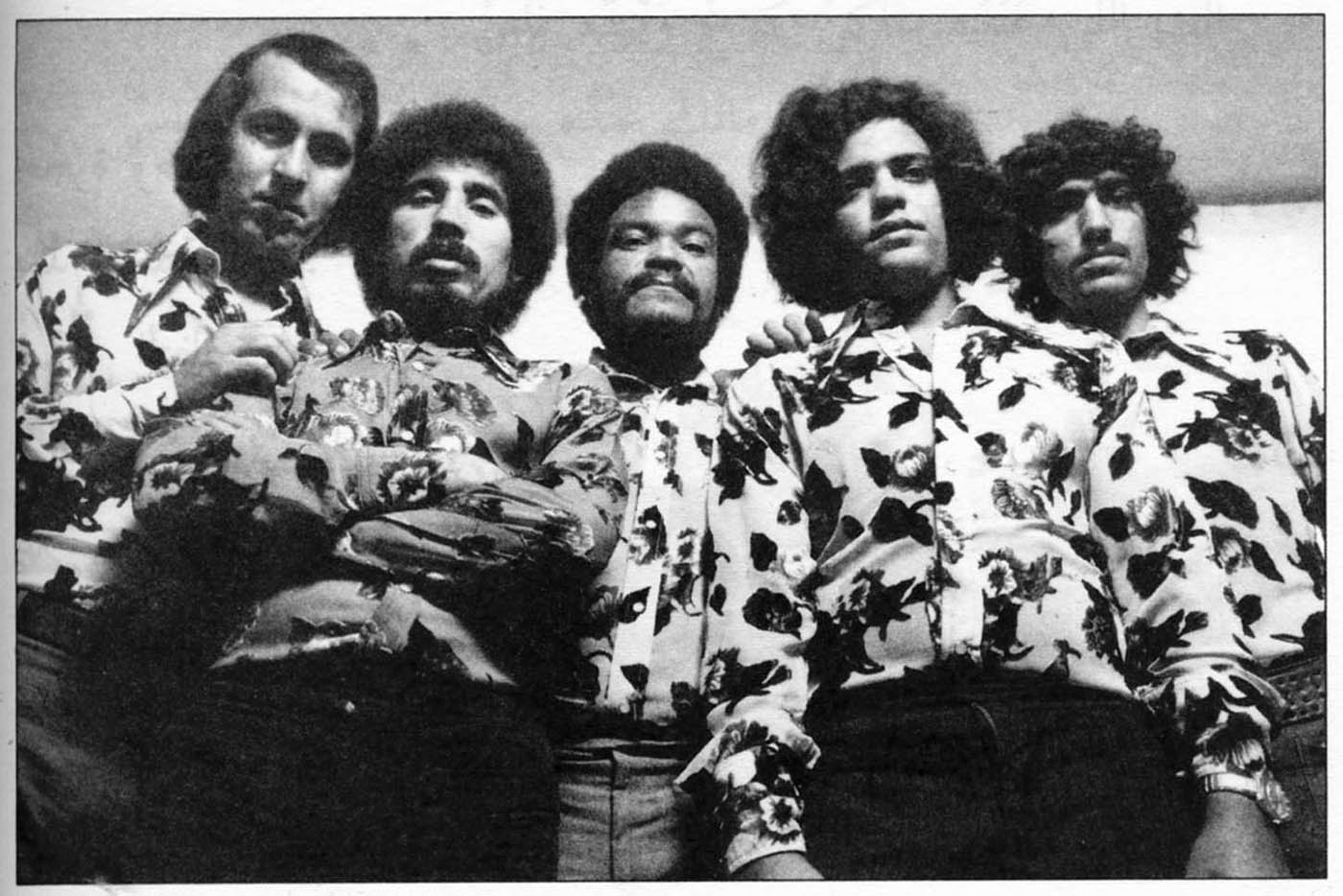

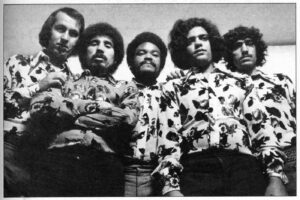

Upon returning to Casablanca, Batma and H’gour began practicing their music with a newfound intensity. During their brief sojourn in France, they had already composed songs like “Mahemmouni,” “Wash Hna Huma Hna,” and “Essiniya,” which would go on to be hugely popular. Recruiting friends Omar Sayed, Allal Yaala, Moulay Abdelaziz Tahiri, and Mahmoud Saadi, they formed a band named Nass el Ghiwane after an old line of malhoun poetry. Blending regional folk styles like Aita with the religious traditions of Sufi orders like the Hamadsha, Gnawa, and Aissawa, Nass el Ghiwane achieved success by renouncing many of the reigning norms of the North African recording industry. They traded string instruments of the classical Andalusi repertoire for simple acoustic instruments of rural folk traditions like the bendir, tabla, and hajhouj.

And they composed, recorded, and performed as a band of equals, rejecting the celebrity culture which glorified singing stars like Umm Kulthum or Abdelhalim Hafez. Their lyrics, sung in Moroccan Darija rather than standard Arabic, eschewed sappy love ballads in favor of poetic ruminations on worry, pain, and loss. At times, these nostalgic laments veered into critiques of the authoritarian regime of King Hassan II, whose brutal suppression of dissent earned this era in Moroccan history the unflattering moniker, “The Years of Lead.”

Indigenous Instruments and Musical Genres

This combative folk music was a radical departure from previous styles of North African popular music, which up until that point had been dominated by orchestral balladeers. In their proud use of local instruments, indigenous genres, and Moroccan language, Nass el Ghiwane represented a threat not just to the reigning stars and the music industry which sustained them, but also to the pro-regime and pan-Arab political commitments which they espoused. The band inspired many imitators and collaborators, who quickly established a genre of radical neofolk music, variously known as “The Ghiwani Phenomenon,” “The Band Phenomenon,” or more simply, “The Phenomenon” (ad-Dhahira), which took the Maghrebi world by storm.

Despite the band’s aesthetic references to rural Morocco as a source of musical inspiration and patriotic authenticity, Paris remained an important meeting point in Dhahira musical networks. Upon emerging in 1970-71, Nass el Ghiwane gained fame through word of mouth, performing at Casablanca cafés and theaters and making occasional appearances on Moroccan television and radio. They signed a contract with the German-British company Polydor, but because Morocco lacked properly-equipped recording studios the label sent the band to Paris in 1973.

The resulting Polydor record, officially titled Nass el Ghiwane but often referred to as the Disque d’Or because of its tremendous commercial success, includes the definitive versions of Ghiwani classics like “Essiniya” and “Ghir Khoudoni.” Highly coveted by collectors, Nass el Ghiwane’s first Parisian record has been copied, re-released, and pirated innumerable times in the five decades since.

Disques Cleopâtre and a Moroccan Music Entrepreneur

At around the same time, a Moroccan expatriate named Brahim Ounassar founded Disques Cleopâtre to cater to Maghrebi immigrants in France. Ounassar would become a close friend and sponsor of Nass el Ghiwane, releasing many of their subsequent records like Hommage à Boudjemaa and Taghounja. He describes the Barbès neighborhood of Paris as “the center of the immigrant world” in the 1970s and 1980s. “On the weekend, people would come to Barbès to purchase this music which connects them to the Bled. The neighborhood was the center of Maghrebi music production in Europe.” Cleopàtre sold over 100,000 Nass el Ghiwane records in the 1970s.

Ounassar also organized Nass el Ghiwane’s 1976 tour of France, a watershed moment in the band’s career. Alongside the popular Moroccan sketch comic duo Bziz and Baz, Nass el Ghiwane performed for audiences of thousands across France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. This included a May 1 performance at the Olympia, again, one of Paris’s largest and most prestigious concert halls. Moroccan observers were proud to note that Nass el Ghiwane were among the first Arab artists to be invited to perform at the Olympia only after the legendary Umm Kulthum and Abdelhalim Hafez.

The Parisian audience, mostly young Maghrebi labor migrants and university students, went wild for this radical Moroccan folk band. Nass el Ghiwane’s performance created “a kind of social delirium,” the Moroccan newspaper Al Alam reported. “Two girls were seized by a strong nervous attack, and some of the chairs were smashed. [The audience] was able to let out their pain and commotion inside a concert hall not made for them.” At least ten people climbed the barriers at that concert to dance on stage with the band. Nass el Ghiwane’s concerts were notorious for this kind of youthful exuberance which reflected the power of the band’s radical aesthetics.

On numerous occasions throughout the 1970s and 1980s, authorities shutdown Ghiwane concerts after crowds descended into riots. That the band was able to elicit such a powerful response on one of France’s largest stages reflects the extent to which Paris was incorporated into North African social and cultural networks of this period.

Belleville Rocks

Paris would continue to be key to Maghrebi musical networks throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Nass el Ghiwane would return to the Olympia in 1977, this time accompanied on tour by fellow Moroccan Dhahira bands the Megri Brothers and Ousmane, the first group to record popular music in Tamazight. Starting in 1981, Parisian listeners could tune into Radio Beur, which played a mix of Dhahira music, Algerian rai, and Maghrebi rock bands like the Rockin’ Babouches and Carte Sejour, which featured a young Rachid Taha. Reporting on the 1982 New Generation Festival in Paris, Moroccan magazine Lamalif noted that: “The Maghreb plays the lead role in France in a new emergent culture derived from the many contributions by children of immigrants […] African, Arab, and Antillean.”

Nass el Ghiwane returned for another concert in Paris in 1980, where the magazine Jeune Afrique (founded in Tunis but relocated to France due to Bourguiba-error censorship) reported that “the spectators were jumping, clapping, even crying, shouting words which the brouhaha rendered incomprehensible. It was a hysterical release. [The band uses] a language which is familiar to the listener, whether he is an immigrant or a simple fellah from the Souss. The ambiance of Paris, its Belleville and Goutte d’Or and Barbès, everything harmonizes with this language.” In addition to many Moroccan and Algerian immigrants, the magazine also interviewed several young French people in the audience, including one who had taught in Morocco through a state-sponsored exchange program. “Making money is not our objective,” Omar Sayed told Jeune Afrique. “A night like this, that is the goal.”

Since then, Dhahira music has lost much of the potency which led its Parisian fans to such hysterics in the late 1970s. Larbi Batma passed away in 1997, leaving Nass el Ghiwane without its charismatic lead singer. Commercially, the band was eclipsed by genres like rai and chaabi distributed far and wide via the then new medium of the cassette tape. Yet Paris remains an important meeting point for Maghrebi musicians and a launching pad for many young artists. In February 2024, Nass el Ghiwane came back for a sold out concert at the Casino de Paris. The night was such a success that the band will return yet again this coming May for another performance. The revolution in Moroccan music which the group initiated on the streets of Paris remains alive and well.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

No visa process in the ’70s. Schengen Area and Maastritch Treaty are from the ’90s. This is completely wrong.