Select Other Languages French.

When Ala Younis first came to Abu Dhabi, she learned that buildings were torn down and rebuilt in 20-year cycles, due to the inclement weather conditions. These 20-year cycles translate into a historical paradox.

On a drive from Dubai to Abu Dhabi, to visit Saadiyat Island’s cultural district (home to the newly-built Guggenheim and Louvre museums), in order to bypass the traffic bottleneck of the city, those in the know would tell you about a detour through the E12 highway, a scenic route stretching across Yas Island, Fahid Island, Al Jubail Island, and finally Saadiyat Island, with an unobstructed view over Mangrove Beach and Ramhan Island. But these are not the continental and oceanic islands of the Mediterranean imagination; instead, these irregular sandy flatlands, a series of loosely interconnected barriers, ridges, and depressions, are the result of relatively recent aeolian, tidal, biological, and anthropogenic processes. The wind, the sea, microbes, and human intervention have shaped these landmasses not into a defined landscape, but rather, into a nebulous space awaiting a final architectural form.

Far away from the monumental skyline of the city center and the multilane Sultan bin Zayed The First Street, connecting Rawda Roundabout and the Corniche across 17 kilometers, on the E12 you can better observe a city in the making — vast spatial voids flanked by wide roads, obviously planned for a densely urban future, spots of carefully manicured greenery meeting straight lines that separate it from sprawling constructions. Sidewalks have not been built yet, and in the near distance, the sea is pristine, both untouched and inaccessible. It is a haphazard combination of different temporalities, some of them still unrealized futures, not yet streamlined with the present. At the end of the ride, on the other side of Saadiyat Island, overlooking the skyline of Reem Island, lies the NYU Abu Dhabi Gallery, where a major exhibition by Kuwaiti-born Jordanian artist, researcher, and curator Ala Younis interrogates these temporalities.

Past of a Temporal Universe, on view in the NYUAD gallery until January 18, 2026, is a mid-career retrospective only in the sense that it traces back two decades of Younis’ work. Trained as an architect in Amman, she uses architecture, visual culture, and archives to excavate lesser-known connections and stories that link the experience of everyday life and its many objects with the transtemporal and transnational networks of politics, economics, industrialization, and state-making in the modern Arab world. Yet once the viewer becomes immersed in these polyphonic and polychronic narratives, where the artist’s voice is almost intentionally absent, complex spiderwebs of ambiguous meaning appear through unexpected connections in history. The ordering and prescriptive nature of chronology breaks down, opening up fresh temporary spaces in which time percolates, leaking out chaotic, fleeting images from vanishing worlds.

One of her most recent projects in the exhibition, Climate Conditions (2025), is anchored in the urbanization of Abu Dhabi, but it will also bring us back to the beginning of architectural imaginaries in the Arab world and her first visit to the emirate. In 2001, when Younis first came to Abu Dhabi, a colleague offered to drive her around to see the city — in the Gulf it is impossible to have a true idea of the scale and shape of urban texture from the perspective of a pedestrian. She thus learned that buildings were torn down and rebuilt in 20-year cycles, due to the inclement weather conditions. Younis then found a technical book about construction works in the Gulf between the 1970s and 1990s, which explained that engineers faced a tremendous challenge in building high rises above ten stories, because the steel becomes rapidly corrupted by water from humidity, and unless they are treated in a certain way, the buildings will collapse.

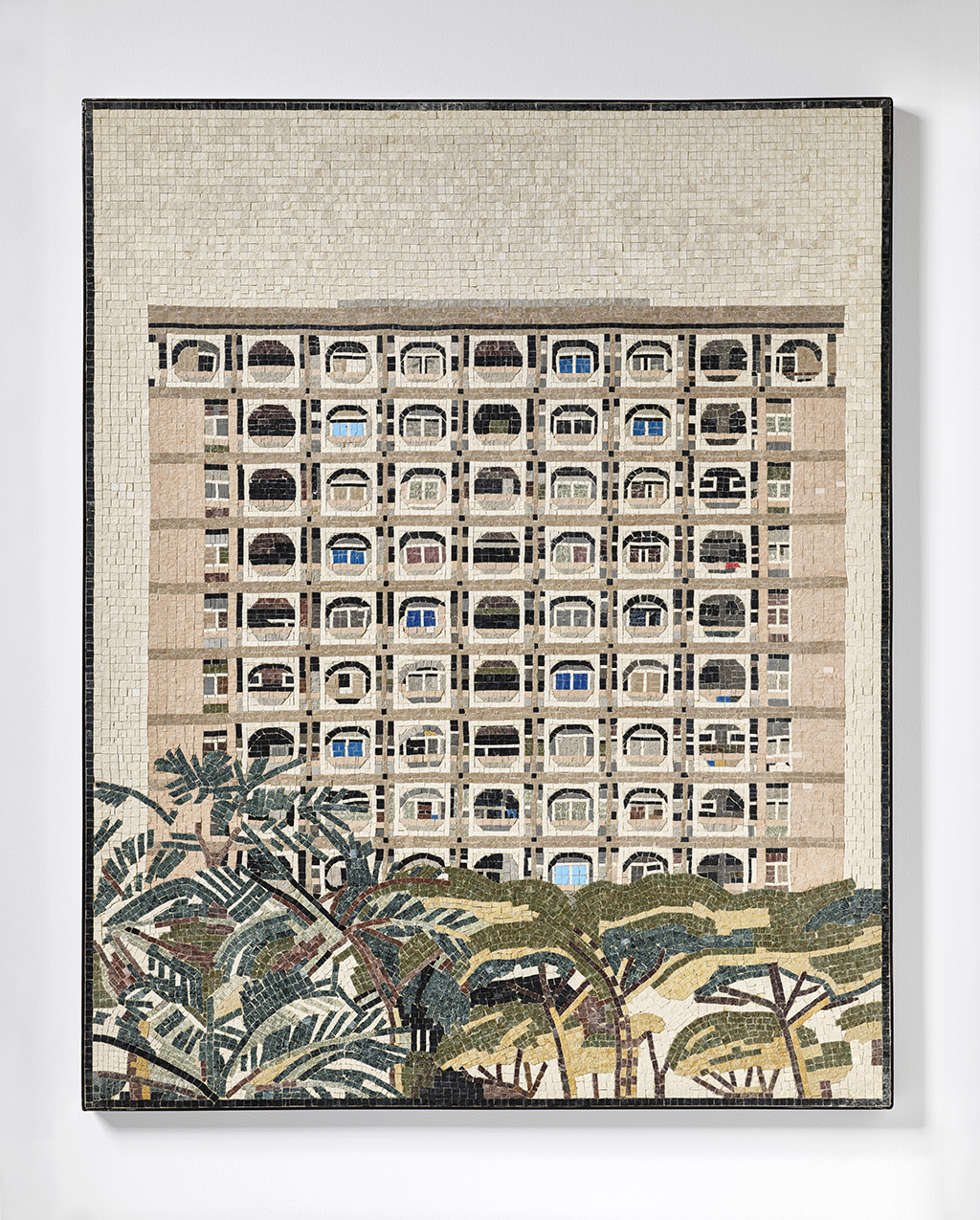

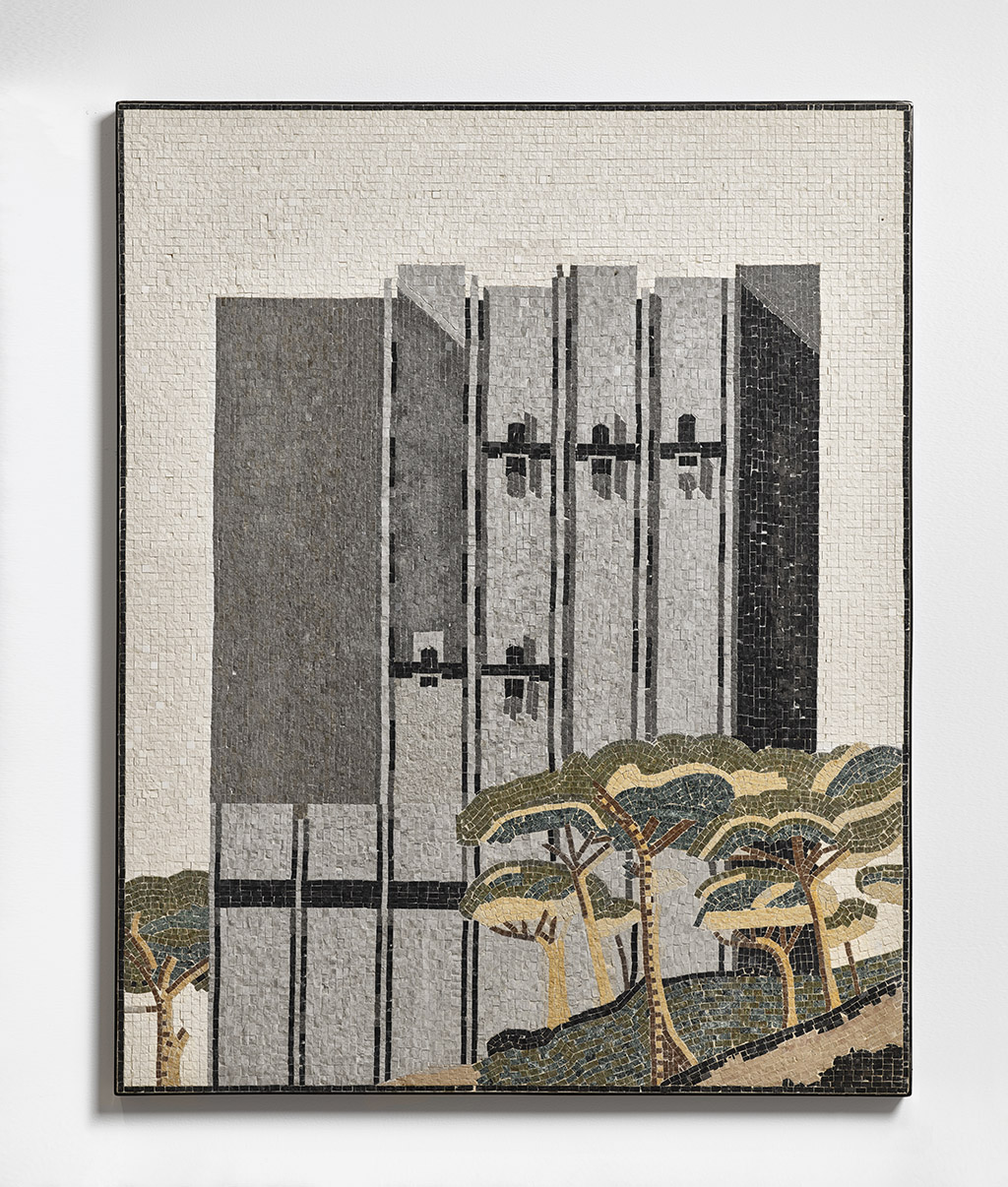

Younis lived in Abu Dhabi for four years, and during that time she began to hear the cracking sound that buildings make in the city, especially at the end of the day, when temperatures are changing and heavy materials began shrinking or expanding, trying to settle back into their natural states after a long day of weathering the intense heat. Climate Conditions is a series of mosaic panels of real buildings in Abu Dhabi, using calcareous materials similar to those of the iconic and largely demolished buildings from the city, in which the tesserae, or mosaic pieces, stand for those cracking sounds, and reminds us of the inescapable relationship between architecture and the environment, at a time when stress heat is one of the most pressing issues in a region that demands extraordinary consumption of natural resources to make human habitation and state-making possible.

In these subtle works that resort to the aesthetic of heritage, Ala Younis inscribes the history of cities beyond the medieval Islamic city, characterized by fortifications, the four-iwan plans of Islamic architecture arranged around a central square, hypostyle mosques, and the use of arches, all indirectly derived from classical monumental architecture and that were meant to last forever. She points us here to the temporary nature of cities in the Gulf that were shaped by weather systems. The same aeolian processes that shaped the islands of Abu Dhabi are at work in the social and physical design of cities on the Arabian Gulf: As the ground heats up, the movement of air between land and sea, from low pressure to high pressure and vice versa, creates benign but seasonal conditions that in turn created these fluid port cities, cities that temporarily attracted merchants, workers, building materials, and generally, encouraged mobility.

But these 20-year cycles translate into a historical paradox: If the life expectancy of a building is two decades, the new structure wouldn’t be a reconstruction as it would be built in the style of that present moment. Thus, the styles from the previous decades would rapidly disappear, which is a double entendre that has led to the idea now commonplace in the western imagination, that Gulf cities do not have a history. Yet today, the Gulf remains as it always was, ever since the emergence of the ports such as Dubai or Manama in the 19th century: a cyclical place; a place in which you remain only for a number of years and not permanently. Younis’ “Corniche Tunnel Art” (2025) is an installation of domestic objects she collected during her time in Abu Dhabi, laid on IKEA shelves, speaking to this temporariness, in which the transient populations making home in these cities choose household items that are easily disposed of and which do not carry loaded memories.

The framed works in the installation are diagrams, visually representing the artist’s personal encounters on the Corniche in Abu Dhabi. They are inspired by the public art made of tiles that adorns the shaded pedestrian tunnels, connecting the Corniche and the city. In the absence of the clearly defined public spaces of the medieval town, Younis is curious about those temporary spaces of assembly in Abu Dhabi, often occupied by transient populations during the day and then later abandoned, without leaving any traces. If modernity is indeed a radical break with a past that it treats as something to be overcome, the transient, ephemeral, instant, and temporary city would be in fact the ideal template for this vision, except that western modernity is much more ambitious and circumscribed at the same time: It is a complex and destabilizing process that involves the breakdown of traditional social structures, and an emphasis on the future.

But dismantling the social order leads to a world without fixed foundations that is in constant need to reinvent itself. The now-time of modernity, as a tabula rasa, is also a time of erasure, of conquest, of resource extraction, of antiquities looting, of infinite expansion, and it is only under the condition of absolute dominance that the absolute present is possible. And here comes the next paradox that haunts Gulf cities: Modernity arrives with a new type of monumentality that aims to secure the foundations of the new, perhaps with more anxiety than the traditional social order ever had, lacking the need for constant reassurance over its meaning.

But how can the forever-new have monumental foundations?

European cities, often built on Roman and medieval towns, do not have to face the abyss of this unsolvable question, and therefore eye Dubai and Abu Dhabi with nervous suspicion when they accidentally expose the problem.

One of Younis’ mosaics of Abu Dhabi is titled after Iraqi architect Rifat Chadirji, and depicts an unrealized project, that of the National Bank of Abu Dhabi, a building commissioned in 1984 but never realized. But there’s another obscure story about Chadirji in Abu Dhabi: In 1977, Chadirji won a competition to design Abu Dhabi’s new National Theatre, but it is unclear whether it was he who ultimately built it, as some accounts point to another architect, Hisham Ashkouri. In any case, the iconic building was completed in 1981. The building has some of the characteristic arches, windows, and coffered ceilings of modern Arab architecture, from an era when Abu Dhabi’s monumental buildings were designed by Arabs, embedded in the region’s history, long before the arrival of starchitects. One etching from the unrealized National Bank of Abu Dhabi project is among a dozen of his architectural drawings in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Chadirji, who died in 2020, is widely regarded as the father of modern Iraqi architecture. He designed more than 100 buildings in the country, including the famous Monument to the Unknown Soldier, later destroyed by Saddam Hussein, and others such as the Central Post Office, the National Insurance Company and the Offices, and Tobacco Warehouses. He also created a 100,000-image archive, deposited at the Arab Image Foundation in Beirut before moving it to the Aga Khan Documentation Center at MIT, chronicling Iraq’s momentous modernization of the built environment. But Chadirji was no traditional architect. While he was inspired by historical Iraqi architecture, he set out to streamline this regional aesthetic with the current international avant-garde style of his generation, an approach that he termed “international regionalism.” Chadirji is one of the protagonists in Ala Younis’ projects “Plan for Greater Baghdad“ (2015 & 2018) and “Battles for a Future Estate – Haifa Street“ (2024).

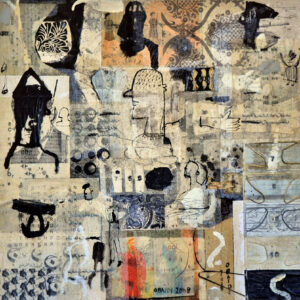

“Plan for Greater Baghdad” centers on the physical structure of the Saddam Hussein Gymnasium, designed by Le Corbusier, composed of architectural models, documents, and found materials. It was inspired by a set of 35mm slides taken in 1982 by Chadirji, depicting the structure, and Younis creates an intoxicating, entropic timeline of the gym’s development as two 25-year timelines leading to its completion in 1980. During this long period, the Middle East and Iraq were engaged in tectonic changes and conflicts, symbolized by five military coups and six heads of state. The artist is probing the ideological associations between monument and state building in the region, with her foreknowledge of future events: How is power designed? Who executes it and who is the audience? What is the relationship between architectural avant-gardes, liberation movements, and authoritarianism?

Her clinical method is the uncovering of archives in all kinds of modalities — past and present, truth and fiction, imaginaries and chronicles, politics and social sciences, landscapes and buildings, hearsay and text. In the exhibition catalogue, she lists the types of archives she accessed, including “Le Corbusier. Concrete structures. Master plans. Iraq’s negotiated oil revenues. Other projects by modern architects for Baghdad and the region. The archives of others and Iraqi archives. The interests and fates of Heads of States. Deputies to Heads of States. Rifat Chadirji, his Iraq Consult, and his peers. Statues and monuments. The Stadium versus the Gymnasium. Jewad Selim. The Tigris River and its meandering through Baghdad. Palm groves, helicopters, informants, doubles and film productions.” The overload of information is crucial here, for it makes it impossible to adopt any singular, unilinear viewpoint.

We are trapped inside a temporal, almost cinematic universe. Avant-garde architects redefine the language of the built environment while building monuments for dictators. As well, landscapes are changing faster than the biosphere can cope; enormous pockets of wealth are created overnight while refugees are roaming the region in all directions; traditional lifeways are being annihilated in the name of progress, although countless opportunities are being created for a nascent middle class. Traditional social values are vanishing while vulgar inequalities are growing; the liberation of women is en route but national projects are failing; nostalgia is stronger than ever in a moment of seemingly infinite progress; wars are lost while pride is swelling; laborers become movable commodities; museums are being built while other museums are being looted. All of these things are true, and all at the same time. Historical time is but chaos.

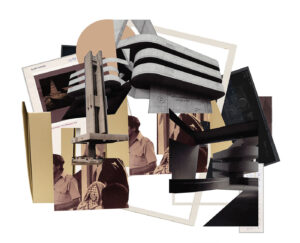

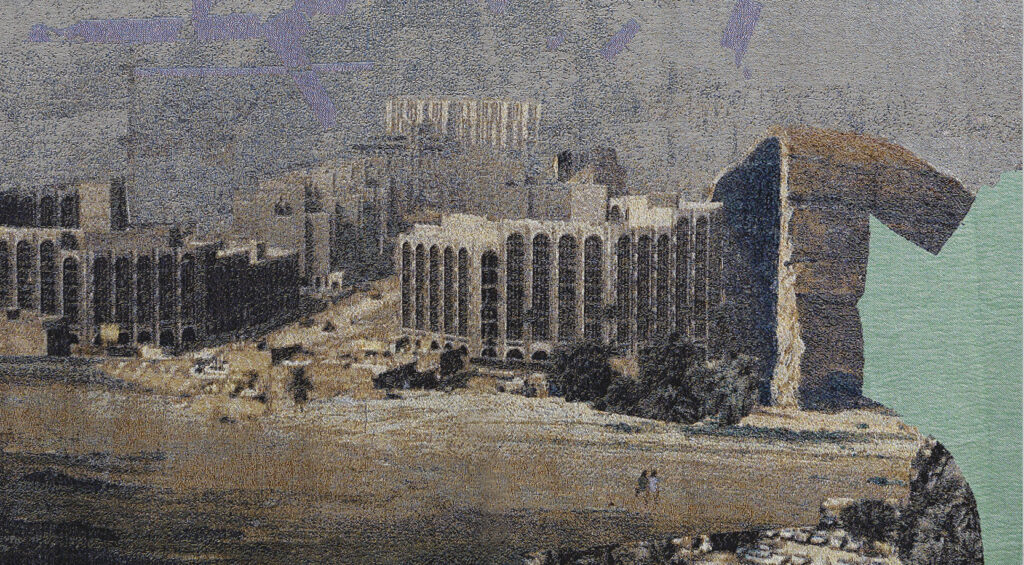

In the project “Battles in a Future Estate – Haifa Street” (2024), the temporal vertigo caused by archival entropy continues to emerge out of architectural forms: A careful forensic investigation into the four decades of the urban and architectural project of Haifa Street in central Baghdad interweaves oil politics, the Iraq War, nationalism, and internationalism — all contradictory elements — reflected in an ambitious plan after 1979 that included the construction of eight large-scale highrises, in a project led by Rifat Charidji, and built by international firms. The long-term goal was to host a nonaligned movement summit in Baghdad, and construction took place during the Iraq-Iran War. These highrises occupy an important place in the intellectual and economic history of the city, as they housed the academics on whose skills the country relied for the production of new realities of development and progress.

The Jacquard-woven cotton textiles in the project, not unlike the mosaics in Climate Conditions, are not a return to heritage or materiality, but an operation that is far more photo-visual and analog, resembling the fragmented grids and textured surfaces of architectural renderings and blueprints. A number of images, temporalities, and historical moments are juxtaposed to form a tapestry, as if we could simultaneously look at so many different perspectives at once, but being fully aware that we cannot. And while the dominance of a singular viewpoint or narrative over another is avoided, grand historical narratives and hegemonic structures are still omnipresent. In “Battles in a Future Estate — Shelter” and “Battles in a Future Estate — Deconstruction,” Younis depicts Haifa Street after the Fall of Baghdad in 2003, when American soldiers entered the apartments in the highrises by force, capturing their interiors on video.

But a historical reference subtly lurks in the background and splits the image on the right: a 1940 painting by Abdul Qadir al-Rassam, Taq Qasra, the ruins of an eponymous palace completed in the year 540 CE. That these works were first shown in Athens at the Tavros Art Space is significant: The Greek city operates in the artist’s imagination as one of those porous borders of the colonial construction of the Middle East, shifting between European capital, site of political and economic struggles, holiday town, migration hub, and heritage symbol. Younis recalls how during her childhood, before the introduction of the euro and the Schengen border, the local currency, the drachma, was devalued to the point that anything would cost millions of drachmas, making Greece a familiar space of uncertainty, western domination, and historical paradox.

The drachma inspired the spectacular installation “Drachmas” (2018), which deals with another currency in the modernization of the Arab world, that of the rise of popular Arab daytime television and its now iconic dramas. Younis describes the mobility of this industry in times of upheaval: “Reproduced exteriors and interiors in studios made way for large numbers of cast and crew not just to move between Beirut, Amman, Baghdad, Cairo, Athens, Kuwait and Ajman studios, but also to navigate war, evade boycotts, save small capital despite currency devaluations and amass a great popularity, in a time that was continuously going through political predicaments.” In the installation, Younis reproduces 42 models of different TV sets spread across these cities, creating a visual transnational history of a cultural phenomenon through built structures, although these structures were neither real nor meant to last.

Returning to the temporary city in the Gulf, the relationship between the monumental modern architecture of Iraq and the rise of Gulf cities is not merely incidental. It’s not simply that Gulf rulers were carefully watching the developments, styles, and pace of construction elsewhere in the region and bringing architects from Iraq in particular, but that they were also learning about how architecture might reshape the state. The monumentality of the built environment in the Arab world that translated into anti-hegemonic, revolutionary, and pan-Arab ideologies came to the Gulf as a sign of economic power in a more diffuse fashion, in which architecture isn’t only built form but an entire management model based on complex supply chains that integrate infrastructure, technology, labor, finance, and land. Perhaps the city is no longer temporary after all and transitoriness is only one representation among many different possible narratives.

In her more recent investigations with Masha Kirasirova for the ongoing project “Study Structure,” on the High Dam in Aswan, Egypt, Ala Younis demonstrates, for example that infrastructure and architecture are more than knowledge transfer from west to east, as it was first conceived in the work of architects such as John Harris who developed the first urban plan for Dubai in the 1960s. At the same time, it served also as a tool of decolonization, particularly in the light of the Egyptian-Soviet cooperation at the height of the Cold War, which extended far beyond architecture, and also included visual culture and artistic education. In Past of a Temporal Universe, once again, the timelines are not unilinear or parallel, but a cross-pollination between contradictory elements that remain always in tension, and that through their fragmented nature, produce a political reality that is neither unified nor stable.

Looking back at the amorphous landscapes, structures, and disjointed timelines in Abu Dhabi on the E12 from Yas Gateway Park to Saadiyat Island, all the incongruous elements can no longer be separated as if they were pieces in a puzzle; they form a strange contemporary assemblage of many different crypto-influences, economic operations, physical forms, and cultural phenomena. This makes us question whether concepts such as “global” or “universal” aren’t slightly obsolete today, particularly in light of all the new grand museums built on the island, since they are the heritage of a slowly fading era of western dominance. Through her practice, Ala Younis cleverly tells us that redistributing historiography doesn’t alter very much the chaos and entropy of our lived experience. But this much we know: We will always live in more than one time and one world, and always have.

Acknowledgements: The title of Younis’ exhibition was inspired by the title of an artwork by the artist commissioned by Darat al Funun – The Khalid Shoman Foundation, in 2018. The writer wishes to thank Mohammed Al Ali, Maya Alison, Gregory Buchakjian, Maria-Thalia Carras, Taymour Grahne, Hoor Al-Qasimi, Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi, Todd Reisz, Vangelis Vlahos, and Ala Younis.