Deborah L. Williams

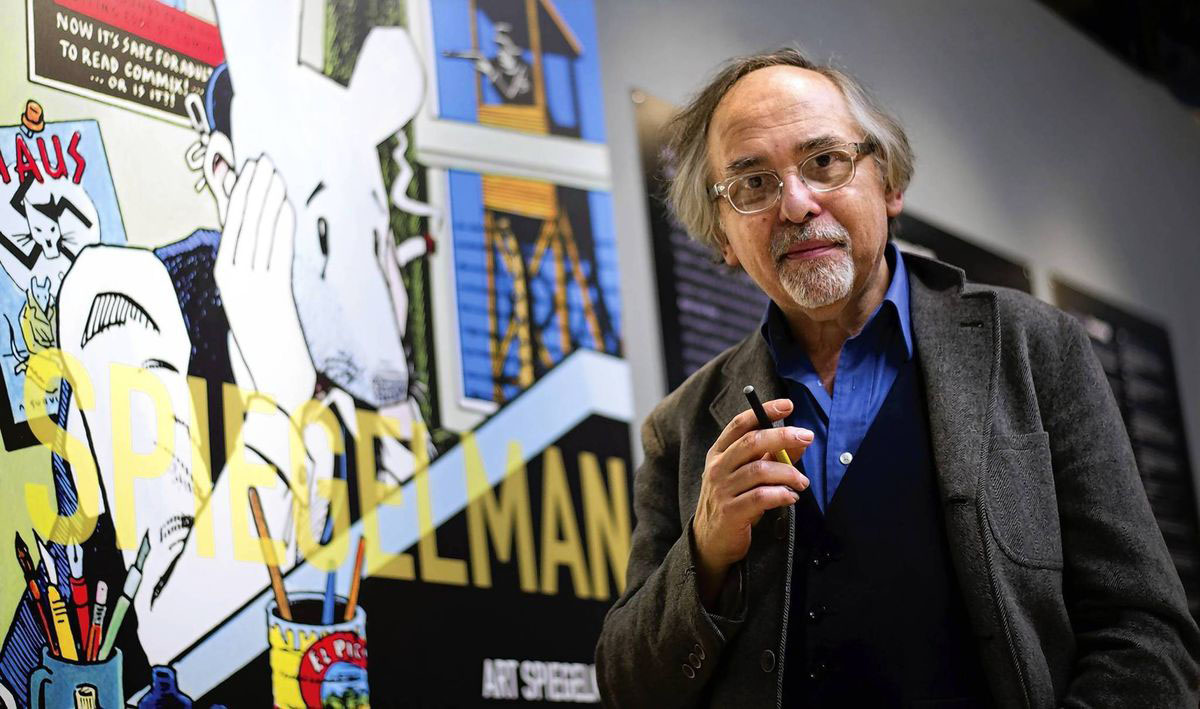

When I saw in the newspaper that a school board in Tennessee had decided to ban Art Spiegelman’s book Maus because because “of its unnecessary use of profanity and nudity and its depiction of violence and suicide,” I realized that my office bookshelves at NYU Abu Dhabi would make the school board members twitch with despair.

What would they think of the shelves full of what can only be called critical race theory, or the rows of books about gender studies and queer literary history—Terry Castle’s Apparitional Lesbian nestled against Foucault’s Discipline and Punish—or, horrors, the stacks of YA fiction, full of representations of magic, human-made climate crises, alternative universes, and revolutions. And, of course, scattered across my shelves are several different editions of Maus, which I’ve taught almost every year for the last ten years.

In fact, my shelves would be a surprise to my colleagues and friends in New York, most of whom were sure that when I moved to NYUAD ten years ago, I wouldn’t have the freedom to teach any of those things. From the moment that the NYUAD project was announced, people were sure that “we” would never be able to teach “them” the things that mattered—an attitude that smacks of more than a little cultural superiority, as if the NYUAD project was intended to somehow bring the light of Western liberalism to the benighted Middle East. There was very little discussion about the NYUAD project might actually involve exchange, conversation, circulation—ideas mixing and being changed in the process.

Some of the course titles for classes in the NYUAD Core (every student is required to take at least four courses in the Core) tell a different story—or rather, they tell multiple stories: “Gender and Representation,” “Novels that Changed the World,” “Feminism and Islamism,” “Revolutions and Change,” and a class taught by the former president of NYU, John Sexton, “The Relationship of Government and Religion.” This last class was mentioned by a faculty member in a 2008 article in New York Magazine, as an example of a course that probably wouldn’t be welcomed in a country that has no separation between church and state. Sexton has been teaching this class in Abu Dhabi since the university’s first year and has continued to do so (interrupted only by the pandemic).

One of the first times I taught Maus in Abu Dhabi, a student in the class, who went to high school in Islamabad, looked at me in shock: “did that really happen?” He was pointing to a picture of Auschwitz prisoners being beaten by Nazi guards. The fact that the prisoners are mice and the guards are cats does not lessen the impact of the images; the student, who had gotten only a very general outline of World War II events in school, was shocked. His surprise was echoed—surprisingly—by a student who grew up in Jamaica, another who grew up in South Africa, and another who went to high school in Qatar and said her school’s librarian kept a copy of The Diary of Anne Frank (wrapped in brown paper) behind her desk. “She would loan it to us if she trusted us,” the student said. And another student, who grew up in a former Soviet republic said that she and her friends felt like World War II was the only thing they learned about.

Those different experiences and the fact that no single experience was in the majority is one of the delights—and challenges—of teaching at NYUAD and, in fact, of living in Abu Dhabi. Yes, the language of instruction at NYUAD is English, which is perhaps best explained as a necessary evil—a polyglot community needs some semblance of a lingua franca—that is also a teaching tool: we talk deeply and specifically about translation and translation theories, about languages of intimacy and estrangement. Each student has a different relationship and yet, at the same time, in the having of these relationships with language, they find ways to connect with one another, despite their differences.

You could say that all of us in the classroom are a bit off balance—students who have never been in a co-ed class, or read a novel for school, or written an essay, or spent time in the company of people unlike themselves. I thought about my student from Islamabad, now long since graduated, when I read about the complacent school board in Tennessee. How will the students in those schools react when they (eventually) encounter unsettling truths or meet people whose experiences are radically different from their own? It isn’t easy to be off-balance, god knows; it takes practice. It is a practice. And if we don’t practice, we end up stuck in our own certainties and fear, unable to imagine lives other than our own.

Ten years into this expat life, I am still asked by friends in the States if I have to cover, if I can drive, drink, wear a bikini. They wonder about the repressed veiled women, about laborers being exploited to the point of death, about the tyrannical Sultan who runs the country. I send photos of people (men and women) on the beach in itsy-bitsy bathing suits; I tell them about the veiled woman I saw the other day gunning the engine on her Mustang when the red light flicked to green; I share my favorite story of how a former student, a Muslim woman, gamed the system of Ladies Nights that are offered at bars all over town: she’d go with her gay male friend, who happily drank her free “Ladies” drinks while his presence as her plus-one would prevent her from getting hit on by other men.

The UAE has a population of about nine million, of which only about 11% are Emirati. The largest non-Emirati group comes from India, followed by Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Philippines. Europe, the UK, and the US get lumped in with “all other countries” in a group of about 1.8 million people. In Abu Dhabi, these groups bump up against each other on the streets, in the malls and parks, on the buses and on the bike paths. While only Emiratis are guaranteed citizenship (there is a complex citizenship application for other nationalities), it is a place where—for the most part—difference is tolerated as a source of strength. Tolerance has become a bit of a buzzword, in fact, as illustrated by the recent creation of the “Ministry of Tolerance.” There is a whole kaleidoscope of diasporas and migrations here; most of us are here to create, in some way, better opportunities for our families, wherever they may be. Living here reminds me that we are all of us wrapped in multiple narratives that sometimes overlap, sometimes entangle, sometimes collide.

That multiplicity exists in Maus, too, which reminds us that in addition to Art’s relationship to his father and his father’s memories of the Holocaust, there is the unspoken story of Art’s stepmother, who also lived through the war, and Art’s mother who kills herself for reasons that Art does not know.

I thought about these multiple narratives when I went back to look at the 2008 New York Magazine article about the founding of NYUAD. The writer referred to Abu Dhabi’s plan to “sink $27 billion into the adjacent Saadiyat Island, which over the next decade will be transformed from a deserted sand bank into the most highbrow cultural theme park on Earth.”

Is “highbrow cultural theme park” the best way to describe a collection of world-class museums, a university, and the buildings devoted to the Abraham Accords? Or perhaps the writer simply couldn’t imagine a narrative about the UAE in which the country is anything other than fuel pump to the world. An actual place where art gets made? That doesn’t fit the story.

Sitting in my office on Saadiyat, I had to laugh at the irony of Maus being banned: the US seems to be closing down while the UAE, contrary to Western expectations, is getting more open.

Except you know what? Watching American fundamentalists gain control isn’t funny. Not at all.