As soon as we announced our plans to travel to Saudi Arabia, friends had questions: how could we give our tourist dollars to Mohammed Bin Salman, particularly in the aftermath of the Khashoggi murder? And had we heard about some wildly contagious virus in a place called Wuhan? We were too curious to be dissuaded. And so in the third week of February 2020, off we went.

Deborah L. Williams

Maraya Hall is covered in mirrors. Its audacity stuns me: a five-hundred seat concert hall, wrapped in 105,000 square feet of mirrored glass and tucked into the hills of Al Ula, a tiny town about four hundred miles northwest of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. On the one hand, mirrors? On the other hand, what better way to honor the setting? The building sits at the top of a long slope, surrounded on three sides by sculpted terracotta cliffs and on the fourth by sand dunes rolling towards the horizon. The mirrored exterior multiplies and extends the vast ancient landscape, playing tricks with perspective: where does the reflected sky end and actual sky begin? Suspended in that seemingly infinite space, I am tiny, an insignificant reflection hovering between here and there, glass and flesh.

From the car, sensibly staying out of the heat, the driver calls out, “worldrecordbiggestmirrorbuilding,” the phrase tumbling from a mouth unused to English. He seems delighted in our delight at the glassy folly. Google confirms the driver’s boast: Maraya — “mirror” in Arabic — does, in fact, hold the Guinness World Record for being the “largest mirror-covered building on Earth.” There is no reason for such a building to be here — or to exist at all, really — and yet there it is, gleaming in the desert sun like a strange spaceship.

Is Maraya a mirrored testament to some sheikh’s desire to be the owner of a “world record”? Does the building glorify its environment or is it an environmental disaster, violating the principles of the Saudi government’s much-ballyhooed “sustainable growth” program? Is it a tacky bauble worthy of the Kardashians? Or a magical mirage come to life?

To all of these questions, yes.

The only way I can explain the power of that shimmering building is to think of it as an architectural manifestation of ostranenie: “making strange.” A Russian term used primarily in literary studies, ostranenie refers to the process of defamiliarizing the familiar: the ordinary is pushed aside and we are invited (or forced) to move away from our usual modes of perception. Letting go of certainty is uncomfortable but it is in that contentious, always disconcerting space of the unfamiliar that we begin to learn — about the world, and ourselves.

Maraya’s loveliness unsettled me: I hadn’t come to Saudi for beauty. I’d come for a quick look at a long-closed country, a larky trip that I figured would simply reiterate what I thought I knew about The Kingdom.

The lark began when my friend Lisa, who like me has lived in the United Arab Emirates for many years, wanted to test out The Kingdom’s newly relaxed visa policies, which allow female tourists to travel unchaperoned and without a non-objection letter from their husband or nearest male relative. The new rules also meant that we wouldn’t have to cover: no face veil, no full-length abaya. “We’ll aim for dowdy,” Lisa said. “Baggy, not much skin.”

I’d wanted to go to Saudi for the entire decade I’ve lived in Abu Dhabi (the capital of the UAE), because whenever people ask me about living in the Gulf, it has served as my go-to negative example. The first question anyone asks me is, “do you have to, you know…” accompanied by a quick swirl around the head, as if indicating a bouffant hairdo or a helmet. No, I say, it’s not like I live in Saudi. Also unlike Saudi: I can drive, I can drink, I can wear a bikini to the beach. Emirati women go abroad to university, hold public office, travel unchaperoned. But in the Western imaginary, all the Gulf states exist as a kind of blur of oil rigs and veiled ladies, with the occasional camel or jihadi frolicking in the background. It’s an easy exotic otherness that is rarely questioned: they are so different from us; and they’re all super-rich, so we don’t have to feel bad about mocking them.

Lisa discovered that we could travel to The Kingdom via the “Winter at Tantora” tour package, which included our hotel rooms in Al Ula, tours of Nabatean ruins, and a “Latin Flavor” concert, featuring the Gipsy Kings and Enrique Iglesias.

Enrique? In Saudi? I thought it was a joke (it wasn’t). And then, the final enticement: Desert X Al Ula, an extension of the site-specific exhibition that had started in California’s Coachella Valley, funded in part by the Palm Springs Desert Council. The Al Ula site would be the first of its kind in Saudi, and would feature Middle Eastern artists, including several from Saudi.

The partnership between Al Ula and Desert X was also — although I didn’t know it at the time — a controversial decision that led some Desert X board members to resign and several artists to boycott the Al Ula project. I knew nothing about Desert X before I went; it was just an unexpected add-on to an already whimsical itinerary. I had no expectations about the art, or anything else — and why would I? The narrative about Saudi that circulates in the West makes no room for art or creativity.

As soon as Lisa and I announced our plans, friends had questions: how could we give our tourist dollars to Mohammed Bin Salman, particularly in the aftermath of the Khashoggi murder? And had we heard about some wildly contagious virus in a place called Wuhan? We were too curious to be dissuaded. And so in the third week of February 2020, off we went.

Our flight to Jeddah, where we’d spend the night before catching the plane to Al Ula, was full of pilgrims — almost all men, many traveling with Mecca-bound tour groups (Jeddah is a common starting point for pilgrimages). Most already wore their ihram, the simple white cotton garment worn by all pilgrims to equalize everyone before God. Even so, there were those whose robes looked like fine linen and others wearing what looked like old sheets. Women’s ihram cover them head to toe but men drape the garment around their torsos, with no undergarment. There was a lot of exposed flesh on that plane.

In Jeddah, we spent the afternoon walking on the Corniche, the promenade along the city’s waterfront, similar to Abu Dhabi’s Corniche, except instead of the Arabian Gulf, we were strolling next to the Red Sea. In both places, families picnicked out of the backs of their cars, children screeched around on scooters, and women with brightly colored running shoes, flashing under black abayas, barreled past on their constitutionals. Abu Dhabi’s Corniche is almost uncomfortably tidy, but Jeddah’s seemed more ramshackle: crumbling balustrades, patchy grass, public art that hadn’t been maintained. I looked around for what I’d seen on Western TV shows — crystal-embellished Bentleys, exotic animals being kept as pets — but all I saw were parking lots full of Camrys, Corollas, and Hondas.

The wealth I didn’t see on the Corniche appeared on our domestic flight to Al Ula: women in abayas sparkling with beading and embroidery, Hermès bags in hand and vertiginous Louboutins on their feet; men in pristine white dishdashas (the traditional robe worn by men in the Gulf), accessorized with au courant sneakers by Yeezy and Balenciaga. The glitteriest people were met on the tarmac in Al Ula by tinted-window limos; the rest of us filed into the low-slung airport, which looks like the one in Palm Springs, as does the landscape: rugged cliffs surrounding a desert valley with a verdant oasis at its center.

The ancient kingdoms that once centered at the Al Ula oasis have long since vanished. Now about five thousand people live there, many of them working on small family-run date and citrus farms. Outside the oasis proper, there are no trees, just billowing gold sand and soaring sandstone cliffs that long-ago rivers carved into steep valleys and slot canyons.

Unlike Abu Dhabi, where almost everyone has at least some English, in Al Ula, our lack of Arabic put us at a disadvantage. In Abu Dhabi, it’s not uncommon to hear Urdu, Gujarati, Hindu, Tamil, French, Farsi, and Tagalog — as well as Arabic and English. Ironically, because of Abu Dhabi’s polyglot nature, I can get by with speaking only English, a fact that is embarrassing to admit. (I blame my middle-aged brain: moving to a new country, at forty, with two kids and a full-time job makes the study of a new language — or anything, for that matter — almost impossible, particularly a language as elegant and complex as Arabic.) Hearing only Arabic swirl around us served as a reminder that we were away, in a place emphatically not our own.

The Nabatean ruins at Hegra — think Petra and Indiana Jones — took us even further from ourselves. So old as to be almost beyond reckoning, these towering structures mark the site of an empire that controlled large portions of the “incense road,” the route followed by camel caravans laden primarily with frankincense, taking them from Yemen across the Arabian Peninsula to Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levant. Looking at the Hegra ruins, it was hard not to wonder what our civilization would look like in three thousand years — and to conclude, grimly, that we’d leave behind only plastic detritus and spent uranium.

From the crumbling remains of Nabatea, we whipsawed to the absolutely contemporary: Desert X Al Ula, curated by two Saudi women, Raneem Farsi and Aya Alireza, in collaboration with Desert X Artistic Director, Neville Wakefield. Most of the 14 site-responsive installations offered meditations on the history of the region and raised questions about how, or if, this ancient landscape could withstand the pressures of human-made climate catastrophe.

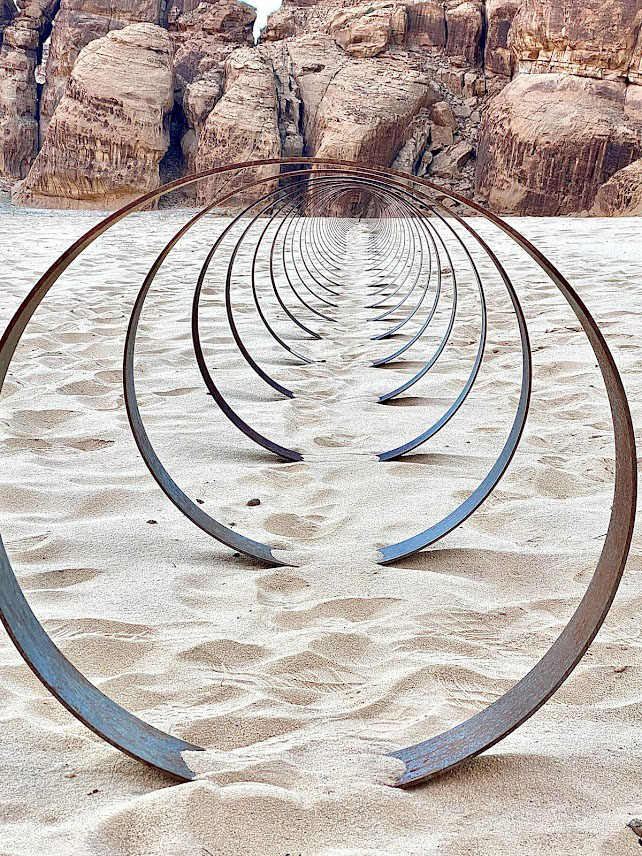

Gleaming from the top of a tall honeycombed rock was an indigo sculpture of a woman sitting cross-legged, palms face up on her knees and a loose veil over her head. Scattered on the sand in front of her were indigo circles of various sizes. To her left, a series of concentric metal rings telescoped across the sand, as if a human-sized Slinky had been stretched on its side. Further afield, a ziggurat split in half, made of plastic shipping pallets and outlined in pink neon; on the other side and down the hill, a silvery obelisk. And beyond that, brightly colored orbs dotted a field of fallen boulders.

The indigo woman is “NAJMA (She Placed One Thousand Suns Over the Transparent Overlays of Space),” a 24th century cosmonaut as imagined by artist Lita Albuquerque. The blue circles were not scattered but in fact precisely placed to mirror the position of the stars over Al Ula on the exhibition’s opening night. As I walked through the site, I saw Najma (the word means “star” in Arabic) again and again, through various openings in the rocks, as if she were the exhibit’s presiding spirit. I felt like a cosmonaut myself, unmoored from all that was familiar.

The sideways slinky was from Rayanne Tabet’s series, “The Shortest Distance Between Two Points.” The line of forty rings represents the last forty kilometers of the Trans-Arabian pipeline, which crosses the borders of five countries. In the exhibit catalog, Tabet explains that she used individual circles rather than a solid tube to illustrate how things shift and change over time, as if to evoke the ghost of the pipeline. Much of the work at DX Al Ula, in fact, had an Ozymandian quality, a reminder that what we think is permanent…isn’t. A warning, perhaps, to be skeptical about our certainties.

Lisa and I hunkered down in the sand to look through the telescoping line of sight formed by the concentric circles. We were joined by two Saudi women doing the same thing, and we took pictures of one another posing in front of the rings. In the picture I have of the two friends, who spoke no English, they flash peace signs and their dusty sneakers peek out from under their robes. And they have pictures of us, who spoke no Arabic, in baggy trousers and dusty sneakers, also flashing peace signs.

One of the most joyful encounters we had was at “Kholkhal Aliaa,” which from a distance looked like a thick black line cutting across a rocky crevice. As we got closer, we saw that the line was in fact a circle, suspended in the crevice as if it had been dropped from a great height and gotten stuck. The circle was inspired by a Bedouin anklet given to the artist, Sherin Guirguis, by her mother. The anklet is painted gold inside and inscribed in Arabic calligraphy with a Bedouin poem. Guirguis said she agreed to be a part of Desert X because “there’s nothing in the history books that contains my narrative [as an Egyptian American woman]. As an artist, as a woman artist, as an Arab woman, I have to go to contentious spaces to create an opportunity for our work to be visible.”

The docent for “Kholkhal Aliaa” was a young man not much older than my son. He’d just graduated from university in the UK and returned home to Al Ula a few months before Desert X began. With a great flourish, he read us the poem in both English and Arabic. “My eyes wide open while the tribes are asleep,” the poem begins, as if to remind us that it is the job of the artist to pay attention where others do not. He finished his recitation with a grin. “On my breaks, I walk around and look,” he said, waving towards the other artwork. “All of it looks different, every time.” To him, DX Al Ula was not a contentious space but a space of constant change.

I remembered his excitement and curiosity when I heard that the Palm Springs City Council pulled its funding for the 2021 Desert X at Coachella. Palm Springs’s mayor, Christy Gilbert Holstege, said she hoped the decision would prompt the Desert X Board to “reform their ways and stop partnering with human rights abusers.” It’s a clear message: art that enters contentious space will pay a steep price.

The City Council did fund a giant J. Seward Johnson sculpture of Marilyn Monroe, in her iconic billowing-skirt pose from The Seven-Year Itch. Marilyn stands directly in front of the Palm Springs art museum, where anyone coming or going from the museum can take a selfie directly into her crotch. The positioning of the sculpture hadn’t been on any of the public planning documents for the renovation of downtown Palm Springs, and people have suggested that it was put there due to pressure from Palm Springs Resorts, in hopes of boosting tourism. In response to the outcry about the statue, which launched the hashtag #metoomarilyn, Mayor Holstege said, “we need interactive works of public art that are Instagrammable — are going to drive tourism on social media.”

Apparently it’s fine to take a picture of Marilyn’s ass because it’s good for business, but we can’t support the artists at DX Al Ula because we disapprove of the government. Desert X Al Ula gives legitimacy to MBS and his thugs, the logic goes, and the entire Winter at Tantora festival is nothing but a publicity stunt designed to cast a flattering light on an unsavory regime. When friends in Abu Dhabi asked how I could support MBS by going to “his” festival, I didn’t have an answer, only another question: how do we draw the lines around where we will or won’t go?

Are there any “innocent” countries? We happily Instagram the Acropolis, built by slave-owning Greeks; marvel at the Colosseum, where prisoners fought to the death for the amusement of Rome. And despite widespread human rights violations, Russia remains a top tourist site: in 2018, approximately 4.3 million people visited The Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, which was also a scheduled port for more than 200 cruise ships from 25 different cruise lines. Why is Putin’s Russia okay but not Saudi? Why do people flock to Epcot or the Grand Canyon when it means visiting a country that herds immigrant children into cages, allows millions of people to sleep in tents or cardboard boxes rather than provide them with adequate shelter, and whose citizens shoot one another with relative impunity?

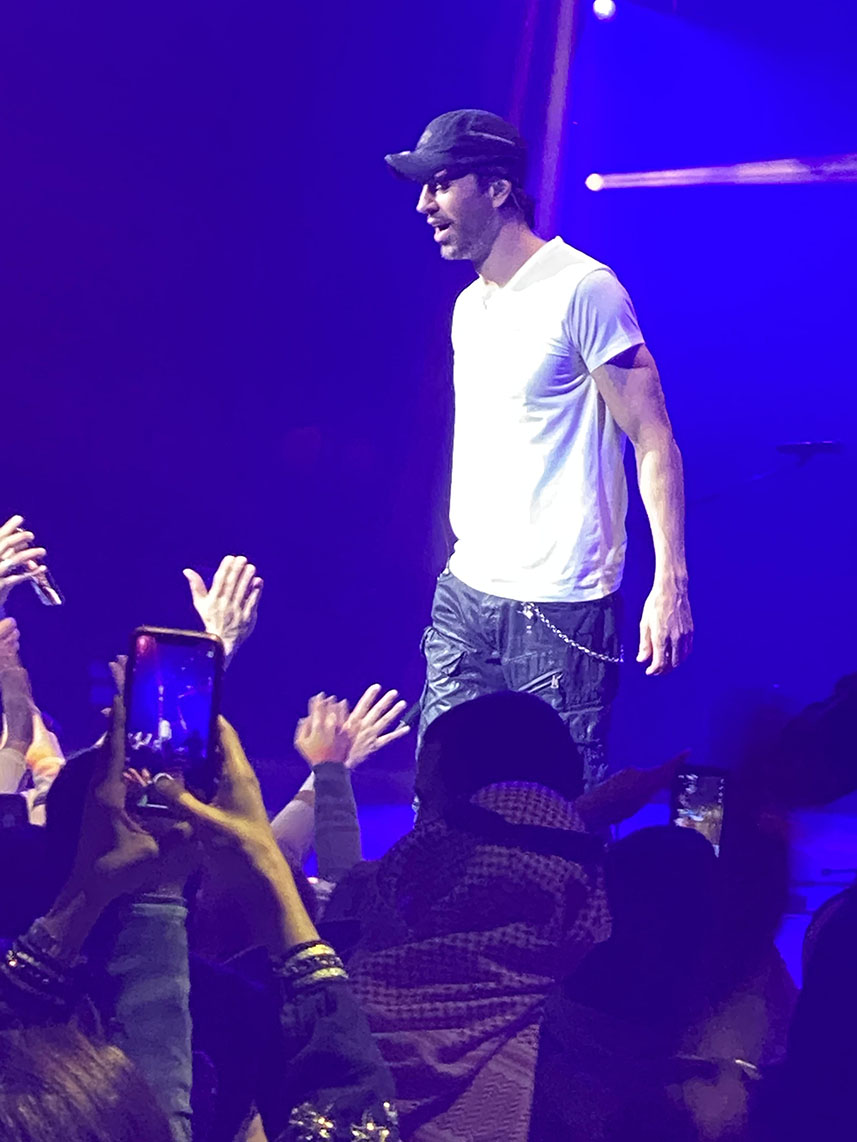

These complex political and philosophical questions danced just below the surface of the Enrique Iglesias concert at Maraya. The night of his show, torch-bearing men on horseback flanked the entrance into the theater, the flames glittering against the mirrored walls so that the entryway seemed to extend forever. Inside, a long hallway lined with flowers and candles led to such an elaborate buffet dinner that Lisa and I thought we’d inadvertently crashed the VIP section. In our nice-but-dowdy outfits, we looked like scullery girls on holiday, especially compared to the other women, most of whom wore headscarves and abayas so bedecked with spangles, sequins, and even feathers that a Vegas showgirl would have felt right at home.

Enrique shook and shimmied, stripped down to a thin white tee-shirt, pranced and posed. He kissed the hands of the veiled women and hugged the others; he skipped into the audience and selfied with dishdasha dudes, then snake-hipped his way back to the stage. Probably everything in the show was tightly scripted (doubtless with some of the racier lyrics removed), but it looked spontaneous. None of the concerts I’ve been to in my life prepared me for the joy of whooping and clapping and boogieing down with hundreds of Saudis to Enrique’s electric beats.

I’m not an Enrique fan — I couldn’t tell you the title of even one song — but I haven’t had that much fun at a concert in a long time. Despite that giddy excitement, Enrique was excoriated on social media for performing in Saudi. Pop stars aren’t supposed to enter contentious space.

Post-Enrique, Lisa and I woke up early for one more trip to DX Al Ula before our flight back to Jeddah. We scrambled to the top of a dune to sit on huge swings designed by the Danish group SuperFlex, and as we swung out over the edge of the hill, we had a bird’s eye view of the entire exhibit. In the heat-induced haze, Najma seemed to float above her rock, like a benevolent indigo spirit. If she returned in the 24th century, what would she see? Would shards of pipeline still remain, would someone be able to recite lines of Bedouin poetry, would there even be people here in three hundred years?

Swooping back and forth on the swings, I started to laugh. The unreality of it — Enrique, mirrors, Nabatea, Najma; Khashoggi’s death at the hands of a repressive monarchic petrostate; the soaring cliffs and vast dome of the sky: where was I?

The Saudi certainties with which I’d arrived had vanished in the sand; I had the strange sense that I would be leaving The Kingdom knowing less than when I had arrived. Or perhaps, paraphrasing Chimamanda Adichie, I would be leaving with many stories instead of one certainty.

On Feb 21st, I flew back to my expat home in Abu Dhabi. That same day Italy sealed its borders to contain the coronavirus, with country after country soon following suit. The doors of our national houses slammed shut, as if walling ourselves off from one another were the answer to the virus. As we’ve seen, though, isolation doesn’t work, not even for those places that are geographically remote, like Australia or New Zealand. What if we’d coordinated our pandemic response as a global endeavor that offered aid to everyone, regardless of wealth or access? What if, that is to say, we’d connected rather than separated?

I come back to that mirrored building in the hills and the reflection of myself, dwarfed by the shimmering landscape. It was hot, I was dusty, my loose clothes were wrinkled, visible proof that there is no perfect condition, no pristine context in which to enter a “contentious space,” to use Guirguis’s phrase. If we refuse to enter these spaces, how can we see anything anew? It is a tremendous luxury to imagine that we don’t have to engage with what makes us uncomfortable, that we can scold or demonize from afar.

I have always wanted to believe that art enables us to think about our world differently; it offers those moments of ostranenie that pry us loose from our insistent certainties and dislodge our comfortable narratives. The Bedouin anklet, in another context, might have looked to me like a shackle, but Guirguis turned it into a shape-shifting object: from a distance a line, up close a crown, and when I stood underneath and looked up, a gold-framed circlet for the infinite desert sky.

Hola! El próximo abril viajaré a Arabia Saudi. Como puedo encontrar estas hermosas obras de arte?

Hello! Next April I will travel to Saudi Arabia. How can I find these beautiful works of art?